Neck pain is a widespread issue, affecting approximately 15% of the general population in today’s world. For automotive repair experts who often find themselves in physically demanding postures, understanding the nuances of neck pain, particularly cervical spondylosis, is crucial. While many cases are benign and resolve on their own, it’s vital to recognize more serious underlying conditions that require prompt medical attention. Furthermore, confidently managing non-urgent cases can prevent unnecessary referrals for self-limiting conditions.

Cervical spondylosis is a broad term describing degenerative changes in the cervical spine. For clarity, it can be categorized into three main clinical syndromes: Cervical Radiculopathy (Type I), Cervical Myelopathy (Type II), and Axial Joint Pain (Type III). It’s also essential to remember that shoulder pathologies can mimic cervical problems, and vice versa, including conditions like adhesive capsulitis, shoulder impingement, and rotator cuff tears. Once a precise diagnosis is established, various management strategies, such as medication, physical therapy, and psychological support, become available.

The diagnosis and treatment of neck pain have long been a challenge for healthcare professionals. The advent of X-ray technology in the early 20th century allowed for the recognition of spinal “arthritis” as a potential cause of neurological issues. Landmark publications in the mid-1930s by Mixter and Barr, and independently by Peet and Echols, highlighted the clinical significance of intervertebral discs, revolutionizing our understanding of spinal disorders.

Epidemiological studies today confirm the high prevalence of neck pain, around 15% in the general population. This rate is even higher in worker’s compensation cases and among professionals, like auto mechanics, who frequently adopt awkward neck postures during work.

While most neck problems are minor and resolve spontaneously, the key challenge for any professional dealing with physical ailments is to identify serious conditions early for timely referral and to manage other cases effectively. This guide focuses on the differential diagnosis of cervical spondylosis, emphasizing common disorders and available management options, particularly relevant for experts in physically demanding fields like auto repair.

Understanding Cervical Spondylosis

The principles governing lumbar spine conditions largely apply to the cervical spine as well. Cervical spondylosis is a non-specific term for degenerative changes in the neck, arising either naturally with age or due to trauma or other diseases. These changes are gradual. The initial step is often biochemical alterations within the disc, leading to dehydration. This reduces the disc’s shock-absorbing capacity, altering spinal biomechanics. Consequently, secondary changes occur in facet joints and ligaments, the other components of vertebral articulation. The body attempts to stabilize the spine, similar to bone fracture healing, by forming bony growths called osteophytes, or “spurs.” Ideally, this leads to auto-fusion. Kirkaldy-Willis described this process in three phases:

I. Dysfunction

II. Instability

III. Stabilization

Phase II instability can manifest as painful micromotion or more pronounced subluxation (degenerative spondylolisthesis). Over time, the spine becomes shorter due to disc height loss and stiffer due to auto-fusion. This process may fully complete in some, while it halts in others. Acute disc herniation can complicate the chronic course. A “soft” disc herniation involves displaced nucleus pulposus or bulging annulus fibrosus. A “hard” disc herniation is a slow-growing, calcified posterior osteophyte. Both can coexist as different manifestations of the same condition.

Cervical spondylosis seems almost inevitable with aging. Radiographic studies show that by age 60-65, about 95% of asymptomatic men and 70% of asymptomatic women exhibit at least one degenerative change on X-rays. Therefore, finding degenerative changes on an X-ray doesn’t automatically indicate a problem. Radiologists rightly advise, “clinical correlation is recommended.”

Clinical Syndromes of Cervical Spondylosis

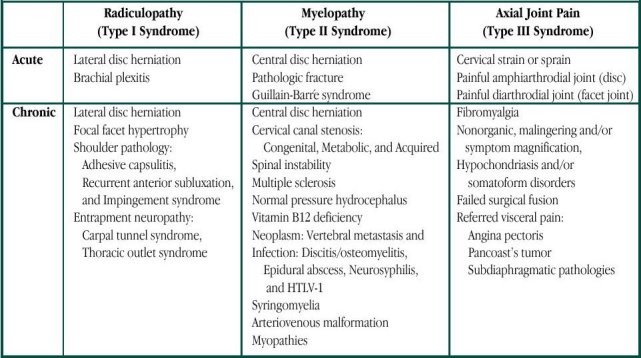

Statistically, cervical spondylosis often presents as mild, self-limiting aches or remains asymptomatic. However, some individuals develop distinct symptoms. Cervical spondylosis leads to three main clinical syndromes:

Type I. Cervical Radiculopathy

Type II. Cervical Myelopathy

Type III. Axial Joint Pain, also known as mechanical neck pain, motion segment pain, “discogenic” pain, facet syndrome, painful instability.

Types I and II involve neurological issues, while Type III relates to painful joint dysfunction. These syndromes can overlap and coexist, but are discussed separately for clarity.

Cervical Radiculopathy (Type I Syndrome)

Cervical radiculopathy is the most easily recognized syndrome, characterized by neck pain radiating to the upper extremity, potentially with pain, weakness, and/or numbness. Radiculopathy results from both compression and inflammation of a spinal nerve, often caused by a “soft” acute disc, a chronic “hard” disc, or, less commonly, facet joint hypertrophy causing posterior compression.

Symptoms follow a specific nerve root distribution, with characteristic reflex, motor, and sensory deficits. The C5-6 disc (C6 nerve root) and C6-7 disc (C7 nerve root) levels are most commonly affected. C6 radiculopathy typically involves reduced brachioradialis reflex, biceps weakness, and pain/paresthesia radiating to the thumb and index finger (C6 distribution). C7 radiculopathy affects the triceps reflex and muscle, with pain/paresthesia radiating to the middle finger.

In the absence of objective neurological deficits, three clinical signs aid in diagnosing cervical radiculopathy. The Spurling’s sign is elicited by laterally bending the neck, bringing the ear towards the shoulder, ideally with slight extension and without rotation. Increased pain on bending towards the affected arm suggests radiculopathy (due to neural foramen narrowing). Conversely, pain worsening when bending away from the painful side points to a non-specific soft tissue issue (muscle or ligament strain).

Two additional mechanical signs are highly suggestive of cervical radiculopathy: relief of radiating arm pain with manual neck traction, and pain relief when the patient rests their forearm on their head. Some patients instinctively adopt this latter position.

These mechanical signs are highly specific but only about 50% sensitive. Their presence strongly suggests cervical radiculopathy, but their absence doesn’t rule it out.

Cervical Myelopathy (Type II Syndrome)

The posterior longitudinal ligament is strongest centrally, directing most disc herniations laterally towards nerve roots, away from the spinal cord. However, the spinal cord can be involved in both acute and chronic processes. Severe cervical myelopathy is clinically obvious, presenting with weakness in all four limbs and a sensory level below which sensation is diminished or absent (pain, touch, vibration, proprioception). Reflexes are hyperactive, possibly with ankle clonus. Muscle tone is increased, causing extremity rigidity. Increased bladder wall tone can lead to urinary frequency and nocturia. Sphincter disturbance is rare without significant trauma.

Pathological reflexes are also present. Hoffmann’s sign (reflex finger flexion upon flicking the middle fingernail) and Babinski’s sign (big toe extension and toe fanning upon sole stroking) are key indicators. Acute or severe myelopathy is usually clear, necessitating urgent neurosurgical referral.

Diagnosing chronic or early cervical myelopathy is much harder due to subtle and variable signs. Patients often report difficulty with fine motor skills, like buttoning clothes. Gait disturbance may be described as unsteadiness rather than frank weakness. Sensory loss is variable, sometimes mimicking peripheral neuropathy with a “glove-and-stocking” pattern. Elderly individuals often have mild, asymptomatic peripheral neuropathy with ankle reflex loss, which can mask the hyperreflexia expected in myelopathy. Increased lower extremity tone may be the only sign. Assess this by having the seated patient dangle their legs and gently shaking the lower leg; in myelopathy, the leg, ankle, and foot move stiffly as a unit instead of being floppy.

Two signs can detect subtle upper extremity myelopathy: the Finger Escape and Grip-and-Release signs, described by Ono et al. The Grip-and-Release test measures hand speed in alternating between fist clenching and full finger extension. Healthy adults can do this rapidly, about 20 times in 10 seconds. Myelopathy slows this and can cause exaggerated wrist flexion during finger extension and wrist extension during finger flexion; wrist neutrality must be maintained. The Finger Escape sign is noted when the patient cannot keep fully extended fingers adducted; the fingers, especially the little finger, involuntarily spread apart.

High suspicion for myelopathy is critical as physical examination diagnosis is challenging. The natural progression of mild cervical spondylotic myelopathy is unclear and unpredictable. Deterioration is usually slow, with periods of stability, but rapid decline can occur. Once severe neurological deficits develop, spontaneous recovery is unlikely, and even surgery may not restore lost function.

Type III Syndrome

Classifying Type III Syndrome can be approached broadly or narrowly. For general understanding, we’ll consider it a single entity, though it’s actually a collection of conditions sharing painful spinal joint dysfunction. Just as hip and shoulder joint pathologies cause pain, so can axial skeleton joints.

The adult spine has two joint types: 1) diarthrodial (synovial gliding joints like facet, costovertebral, atlantoaxial, and sacroiliac joints) and 2) amphiarthrodial (slightly mobile, non-synovial joints). Amphiarthrodial joints include Symphysis type (intervertebral discs) and Syndesmotic type (ligamentum flavum, intertransverse, interspinous, and supraspinous ligaments). These complex structures connect vertebrae and can be pain sources.

Type III syndrome presents as neck pain radiating to areas like the medial scapula, chest wall, shoulder, and head. Vague aching in the proximal arm may occur, but pain below the elbow suggests nerve root involvement. Pure Type III syndrome lacks neurological deficits, as pain originates from the joint(s). Headaches are usually occipital with muscle spasm, sometimes radiating frontally. Pain referred to the medial scapular border is important to recognize to avoid unnecessary thoracic spine scans. Pain is activity-related and relieved by rest. A neck brace should theoretically help, but results are inconsistent due to incomplete neck immobilization even with rigid collars.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for cervical spondylosis is detailed in Table 1. A comprehensive discussion is beyond this scope, but key points are important. Brachial plexitis, or brachial plexus neuropathy, is rare but presents dramatically with sudden, severe pain followed by weakness after weeks. Prognosis is usually good with spontaneous recovery over months to years. The cause is unknown, often linked to prior illness or immunization.

Shoulder problems can easily mimic cervical issues and vice versa. Adhesive capsulitis (“Frozen Shoulder”) involves loss of passive range of motion in all planes, especially external rotation, and can coexist with cervical radiculopathy, particularly in older adults. Its relation to radiculopathy (disuse-related) or reflex sympathetic dystrophy is unclear. Recognizing this is vital as it may persist after radiculopathy resolves and require specific treatment.

Recurrent anterior subluxation (“Dead Arm Syndrome”), seen mainly in young throwing athletes, involves partial shoulder dislocation causing vague distal arm numbness and tingling, superficially resembling radiculopathy. Impingement Syndrome, including supraspinatus tendinitis (or biceps long head tendinitis), can radiate pain down the arm, mimicking cervical radiculopathy. Calcific deposits in inflamed tendons can cause sudden, intense pain (sometimes called bursitis). Rotator Cuff Tear, a tear at the supraspinatus tendon insertion, may occur. Unlike Frozen Shoulder, passive range of motion is full but painful. External rotation is weak, and abduction strength in the first 90 degrees is often lost (“falling arm sign”). Shoulder joint problems should be suspected if pain occurs when the examiner moves the shoulder.

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome is common and can occur with cervical radiculopathy (“double crush syndrome”). Painful numbness, especially at night, wakes patients. They often shake their hand awake in the morning. Tinel’s sign is positive at the wrist, and palmar thumb abduction is weak. Wrist splints at night, NSAIDs, and Vitamin B6 can help mild cases.

Fibromyalgia, or fibrocytis, is a syndrome of unknown cause with widespread pain, tenderness at multiple points, and fatigue, morning stiffness, tingling, anxiety, headache, prior depression, and irritable bowel. There’s no specific test; it’s a diagnosis of exclusion, often poorly responsive to treatment. Recognition is essential to avoid unnecessary surgery. As a patient quoted, “Usually when I go to see the doctors I tell them about the pain that’s worst. If I tell them about everything, they think I’m nuts.”

Management Options

Most cervical spondylosis symptoms are self-limiting. A study comparing placebo to NSAID plus muscle relaxant for acute neck or low back pain showed initial improvement in the treatment group, but the difference disappeared by day 10 because the placebo group improved spontaneously. For patients with normal neurological exams, acetaminophen might be a reasonable first-line treatment to avoid NSAID side effects.

For cervical radiculopathy, neurological examination is key. Significant motor weakness warrants early, non-emergent surgical referral. Otherwise, non-surgical treatment can be tried. Lateral flexion and extension cervical X-rays should rule out instability or structural issues. The main treatment is NSAIDs and cervical traction. Home traction devices are available, and therapist instruction can be helpful. Starting with 8 pounds for 20 minutes thrice daily is generally safe, adjusting up to 15 pounds for muscular individuals. Traction can worsen muscle spasm but often reduces radicular arm pain. Temporomandibular joint problems are a relative contraindication. Supervised physical therapy traction is also helpful, but home traction is often equally effective. Muscle relaxants and analgesics can be added. A 4-6 week trial is reasonable, but earlier surgical referral is always an option. MRI scans are usually diagnostic; sometimes, myelogram/CT scans are needed. Routine CT scans alone are rarely helpful for cervical spondylosis management. Surgery for persistent radiculopathy with clear radiological findings often yields good results.

Cervical myelopathy requires specialist referral, ideally with a cervical MRI. Surgical decisions are individualized due to uncertain natural history and progression of mild myelopathy. Surgery is more considered for advanced symptoms or significant radiographic findings. Laminectomy alone had lower success rates in advanced cases, leading to more comprehensive surgical approaches with improved outcomes in difficult cases.

Type III Syndrome treatment primarily involves “tincture of time.” Initially diagnosed as cervical “sprain” or “strain,” symptoms usually resolve. Chronic cases may be diagnosed as Type III Syndrome.

Some clinicians doubt Type III Syndrome’s validity. Neurological exams are normal. Manifestations are subjective; there’s no “pain meter.” Muscle spasm can be objectively measured but isn’t required for diagnosis. Radiographic correlation is poor, as asymptomatic cervical spondylosis is common with aging.

Type III Syndrome management is challenging, and some cases are intractable. For significant cervical spasm and muscle contraction headaches, biofeedback training for muscle relaxation can be helpful. This can also introduce a psychological pain management approach. “Conservative” long-term physical therapy and therapeutic injections are common, but their efficacy needs scrutiny like surgical interventions. For chronic low back pain, epidural steroid injections were no better than intramuscular injections in a controlled study. Facet steroid injections also showed no sustained benefit in a placebo-controlled trial.

While therapeutic injections are questionable, diagnostic injections can be valuable in Type III Syndrome to identify the “pain generator.” Spinal structures are divided into anterior (discs, vertebrae) and posterior columns (facet joints). MRI and discography assess the anterior column, while SPECT scans and facet injections assess the posterior column. If pain generators are identified, surgery may be considered after careful psychological evaluation using MMPI and clinical psychologist interviews. Coexisting depression or anxiety must be treated pre-operatively. Nicotine addiction should also be addressed due to its negative impact on outcomes.

Even with thorough screening, Type III syndrome surgical results are generally less favorable. However, satisfactory outcomes are possible in carefully selected patients.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Michael Wilson, MD, Associate Chairman and Director of Residency Training, Department of Orthopedics, Ochsner Clinic and Alton Ochsner Medical Foundation, for his assistance with the shoulder pain discussion.

Dr. Voorhies is the Chairman of Ochsner’s Neurosurgery Department.

Table 1. Differential Diagnosis of Clinical Syndromes Resembling Cervical Spondylosis.

| Disorder | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Brachial Plexitis | Sudden onset severe pain followed by weakness; often post-illness or immunization; slow recovery. |

| Adhesive Capsulitis | “Frozen shoulder”; global loss of passive shoulder motion, especially external rotation; may coexist with radiculopathy. |

| Recurrent Anterior Subluxation | “Dead arm syndrome”; in throwing athletes; vague distal numbness and tingling; shoulder instability. |

| Impingement Syndrome | Shoulder pain radiating down arm; pain with shoulder motion; rotator cuff weakness. |

| Rotator Cuff Tear | Weakness in shoulder abduction and external rotation; pain with active shoulder motion. |

| Carpal Tunnel Syndrome | Nocturnal pain and numbness in hand; positive Tinel’s sign; weak thumb abduction. |

| Fibromyalgia | Widespread pain and tenderness; fatigue; sleep disturbance; no objective neurologic signs. |

References

[1] Mixter WJ, Barr JS. Rupture of the intervertebral disc with involvement of the spinal canal. N Engl J Med. 1934;211:210–215. [doi]

[2] Peet MM, Echols DH. Herniation of the nucleus pulposus; a cause of compression of the spinal cord and its nerve roots. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1934;32:924–958.

[3] Treaster D, Burr D.突发性颈部疼痛的患病率和危险因素[颈部疼痛的患病率和危险因素]. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(3):248–249.

[4] Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Bernard TN Jr. 脊柱疼痛. 圣路易斯: 莫斯比; 1992. 病理学和生物力学; 第 2 卷.

[5] Gore DR, Sepic SB, Gardner GM. 无症状志愿者的颈椎退行性疾病. 骨与关节外科杂志. 1987;69(4):512–515.

[6] Bogduk N. 颈部疼痛的分类、病理生物学和自然史. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1994;6(2):135–139.

[7] Wainner RS, Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ, et al. 颈椎根病的临床预测规则. 脊柱杂志. 2007;32(1):E1–E13.

[8] Ono K, Baba H, Kawahara N, et al. 颈椎脊髓病: 脊髓病理学和临床诊断之间的临床研究. 脊柱杂志. 1988;13(12):1746–1758.

[9] Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, et al. 纤维肌痛的先兆和后果. 关节炎和风湿病. 1995;38(8):1119–1126.

[10] Anderson R, Meeker JE, Turk DC, et al. 急性肌肉骨骼疼痛的治疗: 双盲、安慰剂对照试验,比较环苯扎林、布洛芬和两者的组合. 疼痛杂志. 2002;3(2):98–105.

[11] Bohlman HH, Emery SE, Cooper PR, et al. 颈椎脊髓病的手术治疗. 骨与关节外科杂志. 1993;75(7):1048–1062.

[12] Okada K, Shirasaki N, Hosoya T, et al. 退行性颈椎脊髓病的长期结果. 脊柱杂志. 1991;16(11):1299–1307.

[13] Teresi LM, Hayward I, Cann CE, et al. 无症状志愿者中颈椎横截面直径的测量. 使用磁共振成像. 脊柱杂志. 1987;12(6):566–569.

[14] Modic MT, Masaryk TJ, Mulopulos GP, et al. 无症状志愿者颈椎和腰椎的椎间盘疾病: 磁共振成像评估. 放射学. 1985;156(3):695–699.

[15] Basmajian JV. 生物反馈的临床应用. 心身医学. 1977;39(1):48–54.

[16] Carette S, Leclaire R, Marcoux S, et al. 急性坐骨神经痛的腰椎硬膜外皮质类固醇注射治疗. 新英格兰医学杂志. 1997;336(23):1630–1635.

[17] Lilius G, Laasonen EM, Myllynen P, et al. 腰椎关节注射对慢性腰痛的无效性. 脊柱杂志. 1989;14(11):2308–2313.

[18] Van Dyke C, Martin WH, Jr, Whitecloud TS, 3rd, et al. 单光子发射计算机断层扫描在腰椎融合术后腰痛患者中的临床价值. 脊柱杂志. 1993;18(5):679–685.

[19] Slipman CW, Lipetz JS, Jackson HB, et al. 诊断性腰椎关节内注射. 疼痛医学. 2000;1(4):294–321.

[20] Derby R, Howard MW, Grant I, et al. 慢性腰痛患者椎间盘造影的心理学预测因子. 脊柱杂志. 1995;20(10):1147–1152.

[21] Holt EP. 腰痛和腿痛患者的椎间盘造影. 脊柱杂志. 1990;15(2):212–213.

[22] Herron LD, Turner J. 颈椎或腰椎融合术后 10 年的腰痛患者的腰椎融合术结果. 脊柱杂志. 1994;19(11):1822–1829.

[23] Brown TL, Padanilam TG, Lombardi AV, Jr, et al. 吸烟对原发性全髋关节置换术后融合的影响. 骨与关节外科杂志. 1999;81(7):951–957.

[24] Rydevik BL, Holm S, Brown MD, et al. 尼古丁对神经根血管的病理生理学影响. 脊柱杂志. 1994;19(1):1–4.

[25] Holm SM, Rydevik BL, Holmquist B, et al. 尼古丁剂量依赖性地抑制兔椎间盘的营养物质运输. 脊柱杂志. 1992;17(10):1491–1496.

[26] Voorhies DR, Jiang L, Thomas CB, et al. 颈椎椎间盘融合术治疗轴向颈部疼痛. 神经外科焦点. 2003;15(1):FSE3.