Understanding Congenital Hypothyroidism (CH)

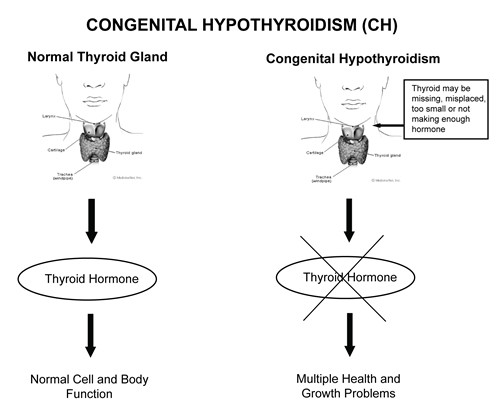

Congenital Hypothyroidism (CH), often diagnosed shortly after birth through newborn screening, is a condition where a baby is born with an underactive thyroid gland. This means the thyroid gland doesn’t produce enough thyroid hormone, which is crucial for normal growth and brain development. The term “congenital” signifies that the condition is present from birth. Hypothyroidism, in general, refers to insufficient thyroid hormone production. While more commonly discussed in adults, particularly women, congenital hypothyroidism presents unique challenges and requires early Ch Diagnosis and intervention in newborns. This guide provides a comprehensive overview of CH, focusing on its diagnosis, causes, and management.

What is Congenital Hypothyroidism (CH)?

Congenital Hypothyroidism (CH) occurs when a baby is born with a thyroid gland that doesn’t produce enough thyroid hormone. The thyroid, a butterfly-shaped gland located at the base of the neck, is responsible for producing hormones that regulate the body’s metabolism, growth, and development. These hormones, including thyroxine (T4), act as messengers that tell cells throughout the body how to function. In infants and young children, thyroid hormone is especially vital for brain development and overall growth. A timely CH diagnosis is essential because thyroid hormone deficiency can lead to significant developmental delays if left untreated.

Causes of Congenital Hypothyroidism: Understanding the Factors Behind CH Diagnosis

Several factors can lead to Congenital Hypothyroidism, impacting the CH diagnosis and subsequent treatment approach:

1. Thyroid Gland Dysgenesis (Missing, Misplaced, or Underdeveloped Thyroid): The most common cause of CH involves issues with the thyroid gland itself. In many cases, babies are born without a thyroid gland (athyreosis), or with a thyroid gland that is underdeveloped (hypoplasia) or located in an abnormal place (ectopic thyroid). Instead of being in the neck, the thyroid might be under the tongue or on the side of the neck. These developmental defects, often occurring for unknown reasons, are typically not inherited and result in insufficient thyroid hormone production, leading to a CH diagnosis.

2. Hereditary or Genetic Causes: In a smaller percentage of cases, approximately 15%, CH is caused by inherited genetic mutations. These genetic changes can affect the thyroid gland’s ability to produce thyroid hormone, even if the gland appears normal in size and location. This form of CH is passed down from parents to their children through genes and requires specific genetic CH diagnosis considerations.

3. Maternal Iodine Deficiency: Iodine is a crucial element required for the thyroid gland to produce thyroid hormone. If a mother has iodine deficiency during pregnancy, it can hinder the baby’s thyroid hormone production, resulting in CH. While iodine deficiency is a rare cause of CH in iodine-sufficient countries like the United States due to iodized salt, it remains a concern in regions with iodine-poor diets. Maternal iodine levels are important factors considered in differential CH diagnosis.

4. Maternal Thyroid Conditions and Medications: Certain maternal thyroid conditions and medications can also contribute to CH in newborns. For example, if a mother takes anti-thyroid drugs during pregnancy to manage hyperthyroidism, these medications can cross the placenta and temporarily affect the baby’s thyroid function. This scenario necessitates careful monitoring and consideration in the CH diagnosis process.

Image alt text: Diagram illustrating hypothyroidism, emphasizing the reduced thyroid hormone production and its impact on the body, relevant to CH diagnosis and understanding.

The Importance of Early CH Diagnosis: Preventing Potential Complications

Most newborns with CH initially appear asymptomatic because they receive thyroid hormone from their mothers during pregnancy, which lasts for a few weeks after birth. However, once this maternal hormone supply diminishes, usually around three to four weeks of age, babies begin to rely solely on their own thyroid hormone production. If they have CH and are not producing enough, symptoms will emerge. Early CH diagnosis through newborn screening is critical to prevent serious health issues.

While most symptoms appear later, some newborns may exhibit signs of CH at birth, including jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes). Other early signs can include:

- Lethargy and Reduced Activity: Babies with CH may sleep excessively and show less movement than typical newborns.

- Feeding Difficulties: Poor feeding and a weak suck reflex can be indicators.

- Constipation: Infrequent bowel movements can occur.

- Hypotonia (Floppy Muscle Tone): Decreased muscle tone may make the baby appear “floppy.”

- Facial Features: Swelling around the eyes and a puffy face can be observed.

- Macroglossia (Large Tongue): An enlarged tongue may be present.

- Skin Changes: Cool, pale, and dry skin are common signs.

- Fontanelle: A larger than normal soft spot on the skull (fontanel) that closes later than usual.

- Umbilical Hernia: A protruding navel.

If CH diagnosis and treatment are delayed, more severe and long-term complications can develop over time:

- Characteristic Facial Features: Coarse and swollen facial features may become apparent.

- Respiratory Problems: Breathing difficulties can arise.

- Hoarse Cry: The baby’s cry might sound hoarse.

- Developmental Delays: Delays in reaching developmental milestones like sitting, crawling, walking, and talking are common.

- Growth Issues: Poor weight gain and stunted growth can occur.

- Goiter: In some cases, the thyroid gland may enlarge, causing a lump in the neck (goiter).

- Anemia: Low red blood cell count (anemia) can develop.

- Bradycardia: Slow heart rate may be present.

- Myxedema: Fluid buildup under the skin, leading to swelling, particularly in facial features.

- Hearing Loss: Hearing impairment can occur.

Untreated CH can lead to significant intellectual disabilities and short stature. Spasticity, unsteady gait, speech delays, and behavioral problems can also develop. Therefore, timely CH diagnosis and intervention are crucial to mitigate these risks.

Treatment for Congenital Hypothyroidism: Management Following CH Diagnosis

Following a CH diagnosis, prompt treatment is essential to ensure healthy development. A pediatric endocrinologist, a specialist in hormone disorders in children, will typically manage the treatment plan.

The primary treatment for CH is thyroid hormone replacement therapy. This treatment is safe, effective, and straightforward. Initiating treatment immediately after CH diagnosis can prevent most, if not all, of the complications associated with CH. However, if brain and nerve damage occurs due to delayed treatment, it is often irreversible.

1. L-Thyroxine Medication: The cornerstone of CH treatment is L-thyroxine, a synthetic form of thyroid hormone that is identical to the hormone naturally produced by the thyroid gland. It is administered orally as a tablet. The pediatric endocrinologist will determine the appropriate dosage of L-thyroxine for the baby and adjust it as the child grows, ensuring optimal thyroid hormone levels. L-thyroxine must be taken daily throughout the child’s life.

L-thyroxine tablets are small and easily administered to infants. They can be crushed and mixed with a small amount of food, formula, juice, or water. It is crucial to ensure the baby consumes the entire dose and not mix it with a full bottle of liquid if the baby might not finish it. While there is no approved liquid form of thyroid hormone for infants, the tablet form is highly manageable.

Adhering to the prescribed L-thyroxine dosage is critical. Excessive L-thyroxine can cause side effects like rapid heart rate, diarrhea, sleep disturbances, and shakiness, indicating an overactive metabolism.

It is important to note that desiccated thyroid, derived from animal thyroid tissue, should be avoided due to inconsistent hormone levels compared to synthetic L-thyroxine.

Soy-based formulas and iron supplements can interfere with the absorption of thyroid hormone. Therefore, it is recommended to administer thyroid medication at least one hour apart from soy formula or iron supplements. Inform the doctor about soy formula use or iron supplementation so medication dosage adjustments can be made if necessary, ensuring effective CH diagnosis management.

2. Regular Monitoring: Ongoing monitoring is a crucial aspect of CH management after CH diagnosis. Regular doctor visits are necessary to track the baby’s weight, height, development, and overall health. Blood tests to measure thyroid hormone levels are also essential. These tests are typically performed every one to three months during the first year of life, then every two to four months until age three, and less frequently thereafter, as determined by the endocrinologist.

3. Developmental Evaluation: Pediatricians may recommend formal developmental evaluations to assess the child’s progress. If developmental delays are identified in areas like learning or speech, early intervention programs can provide specialized services to support the child’s development before school age, optimizing outcomes following CH diagnosis.

Long-Term Outlook After CH Diagnosis and Treatment

Children who receive prompt treatment for CH after CH diagnosis typically experience normal growth and intellectual development, leading healthy and fulfilling lives. However, some children, even with treatment, may encounter learning difficulties in school and might require additional academic support. Some may also experience slightly delayed growth compared to their peers.

If treatment initiation is delayed for several months after birth, there is a higher risk of developmental delays and learning problems. The severity of these delays can vary among individuals. This underscores the importance of newborn screening and early CH diagnosis in ensuring the best possible outcomes.

Understanding Inherited Congenital Hypothyroidism and Genetic Testing After CH Diagnosis

In the majority of CH cases (80-85%), the condition arises from thyroid gland dysgenesis, which is usually not attributed to inherited factors. However, in about 15% of cases, CH is linked to genetic causes, where the thyroid gland may appear normal, but hormone production is impaired. In such instances, inherited CH is more likely. If inherited CH is suspected following CH diagnosis, referral to a genetic counselor or geneticist may be recommended.

Most inherited forms of CH follow an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. This means that both parents must carry a non-working copy of the gene for their child to inherit CH. In autosomal recessive CH, the child inherits two non-working gene copies, one from each parent. While these children have a structurally normal thyroid gland in the correct location, it doesn’t produce sufficient thyroid hormone.

Parents of children with autosomal recessive CH are usually carriers, meaning they possess one working and one non-working gene copy. Carriers themselves do not have CH because the working gene copy compensates for the non-working one.

When both parents are carriers, there is a 25% chance with each pregnancy that their child will inherit CH, a 50% chance the child will be a carrier, and a 25% chance the child will inherit two working gene copies and not be affected.

Image alt text: Autosomal recessive inheritance chart illustrating the probability of inheriting CH when both parents are carriers, emphasizing genetic counseling relevance in CH diagnosis and family planning.

In rare instances, CH can be inherited through X-linked recessive or autosomal dominant patterns. A genetic counselor or geneticist can provide detailed information about the specific inheritance pattern in these cases and the risk of CH for other family members. Genetic counseling is valuable for families with potentially inherited CH after CH diagnosis. Genetic counselors can address questions about inheritance patterns and recurrence risks in future pregnancies.

If inherited CH is suspected after CH diagnosis, genetic testing may be considered to identify the specific gene mutations responsible. Genetic testing, typically performed on a blood sample, can help pinpoint the genetic cause of CH. While genetic testing is not necessary for initial CH diagnosis, identifying the gene mutation can be helpful for carrier testing and prenatal diagnosis in future pregnancies.

Additional Testing Beyond Initial CH Diagnosis

A positive newborn screening result for CH necessitates further diagnostic testing to confirm the CH diagnosis. Blood tests to measure thyroid hormone (T4) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels are routinely performed to confirm CH.

Thyroid imaging tests, such as ultrasound or thyroid uptake and scan, may be used to determine the underlying cause of CH. Ultrasound helps visualize the thyroid gland’s presence, location, and size. A thyroid uptake and scan assesses thyroid structure and function, indicating if the thyroid is in the correct position, of normal size, and functioning properly, aiding in comprehensive CH diagnosis.

Prenatal Testing and Family Considerations After CH Diagnosis

Typically, CH is not detectable before birth, and most cases are not hereditary. For potentially inherited CH, genetic testing can identify only a fraction of hereditary cases.

If a child has inherited CH and the specific gene mutations have been identified, prenatal DNA testing is technically possible in subsequent pregnancies. However, prenatal testing for CH is rarely pursued due to the high effectiveness of postnatal treatment following CH diagnosis. Genetic counselors and physicians can provide further guidance on prenatal testing options if desired.

For families with a child diagnosed with CH, it’s important to understand the risks for other family members. Older siblings of a child with CH are unlikely to have the condition if they are healthy and developing normally. However, if there are concerns, consulting a doctor is recommended.

In future pregnancies, newborn screening is crucial, especially if a previous child had CH. While newborn screening is generally effective, in families with a history of CH, additional diagnostic testing beyond routine newborn screening may be advised to ensure early and accurate CH diagnosis in subsequent newborns.

Prevalence and Demographics of Congenital Hypothyroidism

Congenital Hypothyroidism affects approximately 1 in every 2,000 to 4,000 newborns in the United States. Intriguingly, CH is twice as common in girls compared to boys, although the reasons for this gender disparity remain unknown.

CH occurs across all ethnic groups globally. It is more prevalent in regions with iodine deficiency. In iodine-sufficient areas, CH is more frequently observed in babies of Hispanic, Asian, South Pacific, and Native American ancestry and less common in babies of African-American ancestry.

Alternative Names for Congenital Hypothyroidism

Congenital Hypothyroidism is also known by other terms, including:

- CHT (Congenital Hypothyroidism)

- Cretinism (an older term, less frequently used now)

- Endemic Cretinism (specifically used for iodine deficiency-related CH)

- Congenital Myxedema (referring to the swelling associated with hypothyroidism)

Resources for More Information on CH Diagnosis and Management

For further information and support regarding Congenital Hypothyroidism diagnosis and management, please refer to these resources:

MedlinePlus: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/congenital-hypothyroidism/

The Endocrine Society: https://www.endocrine.org/

MAGIC Foundation (Major Aspects of Growth in Children): www.magicfoundation.org

American Thyroid Association: https://www.thyroid.org/

Disclaimer: This information is for general knowledge and informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Consult with a healthcare professional for any health concerns or before making any decisions related to your health or treatment.