Dyspnea, or shortness of breath, is a frequent complaint in ambulatory care, affecting up to 25% of patients. It can be a symptom of various underlying conditions, ranging from benign to life-threatening. When coupled with chest pain, the diagnostic challenge intensifies, demanding a systematic approach to differential diagnosis. This article provides an in-depth guide to understanding the differential diagnosis of chest pain and shortness of breath, aiming to enhance diagnostic accuracy and improve patient outcomes.

Understanding Dyspnea and Chest Pain

Dyspnea is defined by the American Thoracic Society as a subjective experience of breathing discomfort, encompassing various sensations of varying intensity. These sensations can include air hunger, labored breathing, and chest tightness. Chest pain, similarly, is a broad symptom with diverse presentations, ranging from sharp, localized pain to dull, diffuse discomfort. Both symptoms are subjective and can be influenced by psychological and environmental factors, making clinical assessment complex.

Differential Diagnosis: Shortness of Breath

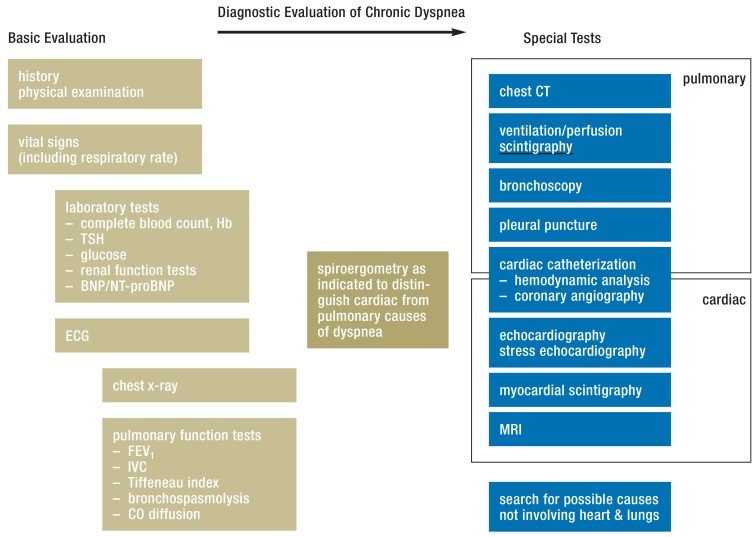

The original article provides a comprehensive overview of dyspnea. Key considerations for differential diagnosis include the temporal course (acute vs. chronic), situational factors (exertional, positional), and potential underlying causes (cardiac, pulmonary, other systemic conditions). The diagnostic process for dyspnea involves a detailed history, physical examination, and often, ancillary tests such as ECG, chest X-ray, pulmonary function tests, and biomarkers.

Common Causes of Dyspnea (from original article and expanded):

-

Pulmonary Conditions:

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): Characterized by airflow limitation, often in smokers. Symptoms include chronic cough, sputum production, and exertional dyspnea.

- Asthma: Variable airway obstruction due to chronic inflammation. Presents with episodic wheezing, chest tightness, cough, and shortness of breath.

- Pneumonia: Infection of the lung parenchyma. Presents with fever, cough, pleuritic chest pain, and dyspnea.

- Pulmonary Embolism (PE): Blockage of pulmonary arteries, often by blood clots. Can cause sudden onset dyspnea, chest pain (pleuritic or anginal), and hemoptysis.

- Interstitial Lung Diseases (ILDs): A group of disorders affecting the lung interstitium. Leads to chronic dyspnea and cough.

- Pneumothorax: Air leakage into the pleural space causing lung collapse. Presents with sudden onset chest pain and dyspnea.

- Pleural Effusion: Fluid accumulation in the pleural space. Can cause dyspnea and chest discomfort.

-

Cardiac Conditions:

- Congestive Heart Failure (CHF): Heart’s inability to pump blood effectively. Causes exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and edema.

- Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS): Sudden reduction of blood flow to the heart muscle. Presents with chest pain (angina), dyspnea, and diaphoresis.

- Valvular Heart Disease: Dysfunction of heart valves. Can lead to CHF and dyspnea.

- Pericardial Tamponade: Fluid accumulation in the pericardial sac, compressing the heart. Causes dyspnea, chest pain, and hypotension.

-

Other Conditions:

- Anemia: Reduced red blood cell count or hemoglobin levels. Can cause exertional dyspnea and fatigue.

- Anxiety Disorders: Panic attacks and anxiety can manifest as dyspnea and chest tightness.

- Neuromuscular Diseases: Conditions affecting respiratory muscles, such as myasthenia gravis or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

- Metabolic Acidosis: Acid buildup in the body. Can cause hyperventilation and dyspnea.

- Obesity: Excess weight can contribute to dyspnea, especially with exertion.

Differential Diagnosis: Chest Pain

Chest pain, while often associated with cardiac issues, has a broad differential diagnosis that includes musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, and psychological causes. When evaluating chest pain, it is crucial to characterize the pain: location, quality, radiation, severity, timing, and aggravating/relieving factors.

Common Causes of Chest Pain:

-

Cardiac Chest Pain:

- Angina Pectoris: Chest pain due to myocardial ischemia, often described as pressure, tightness, or squeezing, typically brought on by exertion and relieved by rest or nitroglycerin.

- Myocardial Infarction (MI): Heart attack, caused by prolonged myocardial ischemia. Pain is similar to angina but more severe, prolonged, and not always relieved by rest.

- Pericarditis: Inflammation of the pericardium. Sharp, pleuritic chest pain, often relieved by sitting up and leaning forward.

-

Pulmonary Chest Pain:

- Pleurisy/Pleuritis: Inflammation of the pleura. Sharp, stabbing pain that worsens with breathing or coughing.

- Pulmonary Embolism (PE): Can cause pleuritic or anginal chest pain.

- Pneumonia: May present with pleuritic chest pain.

- Pneumothorax: Sudden onset chest pain, often pleuritic.

-

Musculoskeletal Chest Pain:

- Costochondritis: Inflammation of the cartilage connecting ribs to the sternum. Localized, tender chest wall pain, often reproducible with palpation.

- Muscle Strain: Pain from strained chest muscles, often related to exercise or injury.

-

Gastrointestinal Chest Pain:

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): Heartburn, a burning sensation in the chest, often related to meals and worse when lying down.

- Esophageal Spasm: Painful contractions of the esophagus, can mimic angina.

-

Psychological Chest Pain:

- Anxiety and Panic Disorders: Can cause chest tightness, discomfort, or pain.

Chest Pain and Shortness of Breath: Combined Differential Diagnosis

When chest pain and shortness of breath occur together, the differential diagnosis narrows, highlighting conditions that commonly affect both the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. Prioritization is crucial, as some combinations indicate life-threatening emergencies.

Key Diagnostic Considerations for Chest Pain and Shortness of Breath:

-

Acute vs. Chronic Onset:

- Acute onset: Raises suspicion for acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, acute asthma exacerbation, and pneumonia. These require immediate evaluation.

- Chronic onset: Points towards chronic conditions like COPD, CHF, ILD, and chronic anemia.

-

Nature of Chest Pain:

- Anginal chest pain (pressure, tightness, squeezing): Strongly suggests cardiac ischemia (ACS, angina).

- Pleuritic chest pain (sharp, stabbing, worse with breathing): Suggests pulmonary causes like pleurisy, pneumonia, or PE, but can also be pericarditis.

- Musculoskeletal chest pain (localized, reproducible tenderness): Less likely to be the primary cause of dyspnea, but can coexist.

-

Associated Symptoms and Signs:

- Fever, cough, sputum production: Favor pneumonia or acute bronchitis.

- Wheezing: Suggests asthma or COPD exacerbation.

- Edema, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea: Favor congestive heart failure.

- Tachycardia, tachypnea, hypoxia: Non-specific but common in many conditions causing both symptoms (PE, pneumonia, ACS, asthma exacerbation).

- Hemoptysis: Can occur in PE, pneumonia, lung cancer, and bronchitis.

- Syncope or dizziness: Suggests cardiac arrhythmia, valvular heart disease, or severe hypotension (PE, ACS).

- Distended neck veins, rales: Suggest congestive heart failure.

- Diminished breath sounds: Suggest pneumothorax, pleural effusion, or severe COPD/asthma.

Diagnostic Approach

The diagnostic approach to a patient presenting with chest pain and shortness of breath should be systematic and prioritize life-threatening conditions.

-

Initial Assessment (ABCs): Assess airway, breathing, and circulation. Provide immediate stabilization if needed (oxygen, IV access, monitoring).

-

History and Physical Examination:

- Detailed history focusing on the characteristics of chest pain and dyspnea, associated symptoms, past medical history, medications, allergies, and risk factors (smoking, cardiac risk factors, history of DVT/PE).

- Thorough physical examination, including vital signs, auscultation of heart and lungs, chest wall palpation, and assessment for peripheral edema and jugular venous distention.

-

Immediate Investigations (Based on Acuity and Suspicion):

- ECG: To rule out acute coronary syndrome (ST-elevation MI, ischemia).

- Oxygen Saturation (SpO2) and Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) if needed: Assess oxygenation and acid-base status.

- Chest X-ray: To evaluate for pneumonia, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, and pulmonary edema.

-

Further Investigations (Guided by Initial Findings):

- Cardiac Biomarkers (Troponin): To rule out myocardial infarction in patients with suspected ACS.

- BNP/NT-proBNP: To assess for congestive heart failure.

- D-dimer: To rule out pulmonary embolism in low to intermediate risk patients (use with clinical probability scores like Wells or Geneva).

- CT Pulmonary Angiography (CTPA): Gold standard for diagnosing pulmonary embolism if PE is suspected.

- Echocardiography: To evaluate cardiac function, valvular disease, and pericardial effusion.

- Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs): For patients with suspected COPD or asthma (not acutely, but in follow-up for chronic dyspnea).

- Ventilation-Perfusion (V/Q) Scan: Alternative to CTPA for PE diagnosis, especially in patients with contraindications to CT contrast.

- Bronchoscopy: May be indicated for hemoptysis, suspected airway obstruction, or to obtain bronchoalveolar lavage for suspected infection or ILD.

-

Differential Diagnosis and Management:

- Based on the clinical picture and investigations, formulate a differential diagnosis.

- Prioritize and manage the most likely and life-threatening conditions first.

- Tailor treatment to the underlying cause.

Biomarkers in Differential Diagnosis (Expanded from original article):

Biomarkers play a crucial role in the rapid differential diagnosis of chest pain and dyspnea, particularly in acute settings.

- Natriuretic Peptides (BNP, NT-proBNP): Elevated levels strongly suggest congestive heart failure as the cause of dyspnea. Useful for ruling out CHF in acute dyspnea.

- Cardiac Troponins (Troponin I, Troponin T): Elevated levels indicate myocardial injury, crucial for diagnosing acute coronary syndrome (MI).

- D-dimer: Elevated levels suggest fibrinolysis and potential thromboembolic disease. High negative predictive value for pulmonary embolism when used with clinical probability scoring.

It’s important to note that biomarkers should be used in conjunction with clinical assessment and other diagnostic tests, not in isolation. For example, troponin can be elevated in conditions other than MI (e.g., myocarditis, PE with right heart strain), and BNP can be elevated in renal failure and pulmonary hypertension.

Conclusion

The combination of chest pain and shortness of breath presents a significant diagnostic challenge. A systematic approach, considering both cardiac and pulmonary etiologies, is essential. Rapid assessment, focused history and physical examination, and judicious use of investigations, including ECG, chest X-ray, and biomarkers, are crucial for timely and accurate diagnosis. Understanding the differential diagnosis and prioritizing life-threatening conditions will improve patient care and outcomes. When faced with these symptoms, a broad yet focused approach, guided by clinical suspicion and appropriate investigations, is paramount to reaching the correct diagnosis and initiating effective treatment.

[