Introduction and Background

A cholesteatoma is an abnormal skin growth, noncancerous in nature, that occurs in the middle ear, specifically behind the eardrum. While some cases are congenital, the most common cause is recurrent middle ear infections. Characterized often as a cyst or sac, a cholesteatoma is formed by shedding layers of skin. The accumulation of these dead skin cells can lead to the growth expanding and invading the tissues within the temporal bone. This invasion can result in a range of complications, affecting facial muscles, hearing, and balance. Cholesteatomas have been known to the medical community for over three centuries. If left untreated, a cholesteatoma can become a serious condition due to its rapid growth and invasive properties. This can lead to significant health issues, some of which can be life-threatening, especially in areas with limited access to advanced medical care. Currently, surgical intervention is the only effective treatment. A comprehensive understanding of the historical and contemporary perspectives on cholesteatoma is crucial for developing effective management strategies. This article offers a concise review of acquired middle ear cholesteatomas, addressing classification, epidemiology, histology, pathogenesis, and providing a detailed overview of current approaches to management and, importantly, Cholesteatoma Diagnosis.

The term cholesteatoma, first coined in 1838 by German anatomist Johannes Mueller, is somewhat misleading. Derived from the words for cholesterol, fat, and tumor, it implies a tumor composed of fatty tissue and cholesterol crystals. However, this nomenclature is inaccurate, much like the term acoustic neuroma. Cholesteatomas originate from the keratinized squamous epithelium of the tympanic membrane and the external auditory canal, which do not contain cholesterol crystals or fat [2]. A cholesteatoma is more accurately described as a well-defined, noncancerous cystic lesion arising from aberrant development of keratinizing squamous epithelium in the temporal bone, often referred to as “skin in the wrong place” [1]. It consists of a matrix (keratinizing squamous epithelium on a fibrous tissue stroma) and a central white mass of keratin debris. This growth is locally invasive and can destroy middle ear structures. Persistent infection can exacerbate the destructive nature of cholesteatomas, amplifying their osteolytic effects [1].

Cholesteatomas are classified into two main types: congenital, primarily seen in childhood, and acquired, further divided into primary and secondary. Primary acquired cholesteatomas develop without a prior history of otitis media or existing eardrum perforation. Secondary acquired cholesteatomas, conversely, are associated with pre-existing perforations, often marginal or large central perforations [3]. Once a cholesteatoma enters the middle ear cleft (comprising the mastoid air cell, antrum, aditus, attic, middle ear, and Eustachian tube), it can invade surrounding structures, leading to enzymatic bone destruction.

Patients with cholesteatoma may experience a range of symptoms, including hearing loss, foul-smelling ear drainage, recurrent ear infections, a feeling of fullness in the ear, dizziness, facial muscle weakness on the affected side, and earache. Cholesteatoma diagnosis is achieved through a combination of otoscopic examination, CT scans, MRI, and tympanometric and audiometric tests. Medical treatment alone is insufficient to cure cholesteatoma; surgical intervention is necessary. Pre-existing infections are managed with local and systemic antibiotics to ensure a dry ear before surgery. The primary surgical objective is to remove the cholesteatoma and clear any infection. Surgical techniques include canal wall up (CWU) and canal wall down (CWD) mastoidectomies. These procedures may involve eardrum reconstruction, removal of bone behind the ear, or addressing hearing loss. A second surgery may be required, typically 6 to 12 months post-initial surgery, to ensure complete cholesteatoma removal and allow for hearing bone reconstruction if needed.

Review

Classification

Congenital Cholesteatoma

Congenital cholesteatomas originate from embryonic epidermal cells that remain in the temporal bone or middle ear cleft. They can develop in various locations, including the middle ear, petrous apex, and cerebellopontine angle, each potentially causing different symptoms. In the middle ear, congenital cholesteatomas typically present with conductive hearing loss and appear as a whitish mass behind an intact tympanic membrane. They may be discovered during routine check-ups or myringotomy in children [4]. In some cases, they can spontaneously rupture through the tympanic membrane, mimicking chronic suppurative otitis media with ear discharge. Levenson’s criteria are used to define congenital cholesteatomas: an intact pars tensa and pars flaccida, no history of eardrum perforation, and no prior ear surgery.

Acquired Cholesteatoma

Acquired cholesteatomas are further categorized into primary and secondary types.

Primary Acquired Cholesteatoma

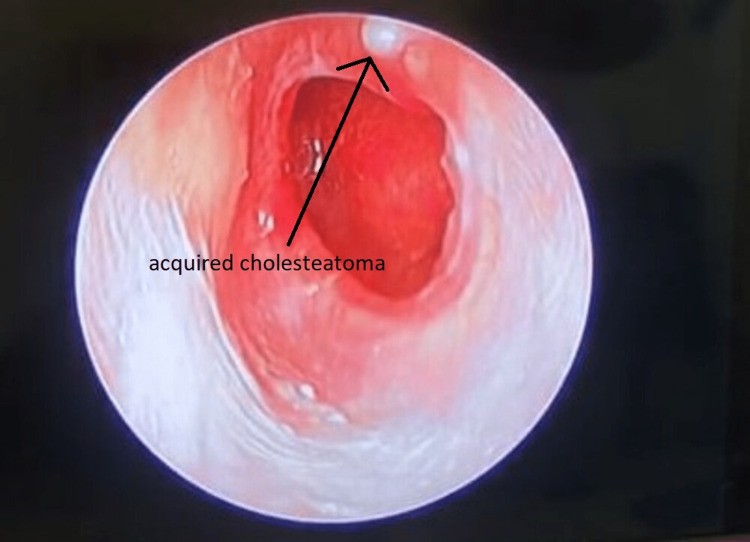

Primary acquired cholesteatoma develops without any prior history of otitis media or pre-existing perforation. Figure 1 illustrates an acquired cholesteatoma. Several theories explain its origin:

- Invagination of pars flaccida: Persistent negative pressure in the attic area of the middle ear creates a retraction pocket in the pars flaccida. Keratin debris accumulates in this pocket, and if infected, the keratin mass expands towards the middle ear. The proximal end of this expanding, invaginated sac becomes an attic perforation.

- Basal cell hyperplasia: Subclinical pediatric infections can cause proliferation of the basal layer of the pars flaccida. An attic perforation forms when the expanding cholesteatoma erodes through the pars flaccida.

- Squamous metaplasia: The normal pavement epithelium of the attic undergoes metaplasia into keratinizing squamous epithelium due to subclinical infections or otitis media with effusion.

Secondary Acquired Cholesteatoma

Secondary acquired cholesteatoma arises in the presence of a pre-existing perforation in the pars tensa, often associated with large central or posterosuperior marginal perforations. Theories of its development include:

- Migration of squamous epithelium: Keratinizing squamous epithelium from the external auditory canal or the outer surface of the tympanic membrane migrates through the perforation into the middle ear. Tympanic annulus perforations, such as those resulting from acute necrotizing otitis media, are particularly susceptible to squamous epithelium proliferation.

- Metaplasia: Recurrent middle ear infections through the pre-existing perforation can induce metaplasia of the middle ear mucosa [5].

Figure 1. Acquired cholesteatoma.

Epidemiology

The reported annual incidence of cholesteatomas is approximately 3 per 100,000 children and 9.2 per 100,000 adults, with a male to female ratio of 1.4:1 [6]. Middle ear cholesteatomas are more common in individuals under 50 years of age, while external auditory canal (EAC) cholesteatomas are more prevalent in the 40-70 age group. A genetic predisposition is suspected [7]. Cholesteatomas are more frequently observed in white populations and less commonly in Asian, American Indian, and Alaskan Eskimo populations [8].

Histopathology

Macroscopically, a cholesteatoma appears as a whitish, ovoid or round, fragile mass with a thin wall containing a macerated or pultaceous substance. Microscopically, it is composed of three layers: the cystic content, the matrix, and the perimatrix [9]. The cystic content is primarily composed of fully differentiated anucleate keratin squames mixed with sebum and necrotic or purulent debris. The cholesteatoma matrix is made up of stratified, hyperproliferative squamous epithelium, similar to skin, with granular, lucid, spinal, and basal layers. The perimatrix (lamina propria), the outermost connective tissue layer, contains inflammatory cells such as fibrocytes, lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophil leukocytes [10].

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of cholesteatoma can be explained by four main theories:

- Invagination Theory (Retraction Pocket Theory): This theory suggests that cholesteatomas originate from retraction pockets in the pars flaccida, caused by negative middle ear pressure and recurrent inflammation [12]. Desquamated keratin accumulates in these pockets, leading to cholesteatoma development.

- Epithelial Invasion or Migration Theory (Immigration Theory): This theory posits that eardrum perforations precede cholesteatomas. Squamous epithelium from the eardrum invades or migrates into the middle ear through traumatic or surgical damage to the tympanic membrane [8].

- Squamous Metaplasia Theory: This theory proposes that the middle ear mucosa can undergo metaplastic transformation into keratinizing epithelium, ultimately leading to cholesteatoma formation [13]. Tympanic membrane lysis and perforation from an enlarging cholesteatoma can then resemble acquired cholesteatoma.

- Basal Cell Hyperplasia Theory (Papillary Ingrowth Theory): According to this theory, cholesteatomas form when keratin-filled microcysts, buds, or pseudopods from the basal layer of the pars flaccida epithelium infiltrate Prussak’s space’s subepithelial tissue [14].

Cholesteatoma Diagnosis

Effective cholesteatoma diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical examination and advanced diagnostic tools. The diagnostic process includes:

Otoscopic Examination

Otoscopy, including video-otoscopy, otomicroscopy, and video-telescopy, is the most direct and crucial method for eardrum inspection in cholesteatoma diagnosis [15]. Adequate illumination and brightness are essential during otoscopic examination. Complete removal of ear canal obstructions like cerumen, crusts, debris, and granulation tissue is necessary to visualize hidden areas and avoid misdiagnosis. Careful examination of the entire eardrum, particularly the attic and posterosuperior quadrant (common sites for acquired cholesteatoma), is vital [16]. Cholesteatomas often present as squamous debris accumulation in a retraction pocket. Granulation tissue or a polyp in the ear canal should be considered indicative of cholesteatoma until proven otherwise. Caution is advised during polyp removal due to potential attachment to ossicles or the facial nerve. The goal of otoscopic examination in cholesteatoma diagnosis is to identify lesions suggestive of cholesteatoma or its precursor, a retraction pocket. Clinicians must differentiate cholesteatoma-related lesions from similar lesions seen in otitis externa during outpatient evaluations [17].

Radiological Examination

CT Scan

Computed Tomography (CT) is the primary imaging modality for assessing cholesteatoma severity and guiding surgical planning. Repeated High-Resolution CT (HRCT) scans before surgery help determine disease extent, potential bone damage, anatomical variations (e.g., middle ear hypoplasia, jugular bulb variations, facial nerve bony dehiscence, sclerotic mastoids, anterior sigmoid sinuses), and complications like tegmen dehiscence and labyrinthine fistulas [18, 19]. CT scans are excellent for detecting bone involvement in cholesteatoma diagnosis. However, CT has limitations in evaluating soft tissue changes, such as membranous labyrinthine or intracranial involvement [20]. Post-tympanomastoid surgery opacification on CT can also reduce accuracy in assessing recurrence or residual disease [21]. Furthermore, CT cannot reliably differentiate between granulation tissue and cholesteatoma.

MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) provides complementary information due to its superior soft tissue contrast, enhancing diagnostic accuracy in cholesteatoma diagnosis [22]. Cholesteatomas typically appear hypointense/isointense on T1-weighted images (T1WI) and hyperintense on T2-weighted images (T2WI) compared to brain tissue. In post-surgical ears, granulation or scar tissue, and bloody serous or proteinaceous fluid, also show hyperintense signals on T2WI [23]. Cholesteatomas may exhibit less signal intensity on T2WI or constructive interference in fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition (FIESTA) compared to granulation tissue, but can also be undetectable on these sequences. Contrast-enhanced T1WI can aid differentiation [24], as cholesteatomas typically do not enhance, while granulation tissue does. However, standard MRI sequences may not always detect cholesteatomas in recently operated temporal bones [25].

Ancillary Diagnostic Tools

Tympanometric and Audiometric Tests

Tympanometric and audiometric tests are valuable ancillary tools in cholesteatoma diagnosis. Audiometric testing identifies conductive hearing loss. Mixed hearing loss, including a sensorineural component, may suggest labyrinthitis [26]. The Rinne test can rule out sensorineural hearing loss, while the Weber test detects conductive hearing loss. Hearing may be normal if the ossicular chain is uninvolved. Paradoxically, a cholesteatoma can sometimes transmit sound across an ossicular gap, resulting in seemingly unaffected or mildly diminished hearing even with ossicular damage. This is known as “silent cholesteatoma,” “conductive cholesteatoma,” or “cholesteatoma hearer” [27]. Tympanometric testing, often used with audiometry, assesses middle ear health. Tympanometry may indicate a perforated eardrum (less common in children than adults) and reduced compliance on the affected side. However, like audiometry, tympanometry may not always accurately reflect middle ear status, and no specific tympanometric pattern definitively diagnoses cholesteatoma [28].

Treatment

CWU Procedure

The Canal Wall Up (CWU) procedure, also known as intact canal wall mastoidectomy, preserves the posterior bone meatal wall while removing the cholesteatoma through a combined meatal and mastoid approach. This avoids an open mastoid cavity [29], leading to dry ears and facilitating hearing system reconstruction. However, there is a risk of residual cholesteatoma. Long-term follow-up is crucial due to the high risk of recurrence or residual disease. Some surgeons recommend routine re-exploration after about six months. CWU techniques are indicated in select cases [29]. Disease eradication in CWU is achieved via combined approaches or intact canal wall mastoidectomy, cortical mastoidectomy, and the posterior tympanotomy approach, creating a window between the mastoid and middle ear through the sinus tympani in the facial recess [30].

CWD Procedure

The Canal Wall Down (CWD) procedure exteriorizes the affected area by leaving the external auditory canal and mastoid cavity open. Procedures like atticotomy, modified radical mastoidectomy (MRM), and radical mastoidectomy are commonly used for atticoantral disease [31]. Post-CWD surgery, patients must avoid wet conditions (swimming, bathing, rain) to prevent complications such as otorrhea (ear drainage), otalgia (ear pain), vertigo, and dizziness [32].

Reconstructive Surgery and Conservative Treatment

Myringoplasty and tympanoplasty can restore hearing, performed either during the initial surgery or as a secondary procedure [33]. Conservative treatment, involving suction clearing under an operating microscope, has limited application for cholesteatoma, typically reserved for small, easily accessible cases [34]. Regular check-ups and repeated suction clearing are essential. Conservative management may also be considered for patients over 65, those unfit for general anesthesia, or those who decline surgery [35]. Polyps and granulations can be chemically cauterized with silver nitrate or trichloroacetic acid or surgically removed with cup forceps. Aural toilet and dry ear precautions are also important aspects of conservative management [36].

Conclusions

Early and accurate cholesteatoma diagnosis is paramount for effective treatment and management. Both traditional and advanced diagnostic methods, including audiometric tests, tympanometric tests, X-rays, CT scans, and MRIs, play crucial roles in cholesteatoma diagnosis. Increased awareness of cholesteatoma is needed to facilitate earlier detection. Symptoms like persistent, often foul-smelling ear discharge and gradual hearing loss in the affected ear should prompt investigation. A thorough understanding of relevant anatomical structures, their relationship to middle ear function and management, involved histology, and appropriate surgical procedures is essential. CWU and CWD procedures, tailored to individual patient needs and disease severity, are necessary for successful treatment and hearing preservation.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.