INTRODUCTION

Ankle sprains are incredibly common injuries, not just in athletes but also in everyday life. It’s reported that a significant percentage, around 20%, of individuals who experience an acute ankle sprain go on to develop chronic ankle instability (CAI). This condition arises when functional rehabilitation after the initial sprain is unsuccessful, leading to persistent problems. Distinguishing between functional and anatomical ankle instability is crucial because it dictates the most effective treatment approach. Therefore, accurate Chronic Ankle Instability Diagnosis is the first and most vital step in managing this condition effectively, whether you’re an athlete, an automotive technician constantly on your feet, or anyone in between.

While ankle sprains might seem straightforward, chronic ankle instability is a complex issue that isn’t always well understood. The problems associated with CAI can be significant, often involving proprioceptive deficits – a reduced sense of balance and position – and increased ligament laxity, meaning the ligaments are looser than they should be. These impairments can significantly impact daily activities, from simple tasks like walking and jumping to demanding physical activities at work or in sports. For professionals in fields like automotive repair, where mobility and balance are essential for navigating shop floors and working in various positions, understanding and addressing chronic ankle instability is paramount.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF ANKLE SPRAINS AND CHRONIC INSTABILITY

The ankle is frequently injured, especially in sports. In fact, ankle injuries account for a substantial 10–30% of all sports-related injuries. Studies indicate that in the general population, 2–7 people out of every 1000 will experience an ankle sprain each year. Certain populations are at even higher risk. For example, military personnel have been shown to experience ankle sprains more frequently than civilians, with rates as high as 58 per 1000 person-years in the U.S. military. This highlights that professions requiring physical exertion and agility, like automotive technicians, may also be at increased risk.

ETIOLOGY AND CLASSIFICATION OF CHRONIC ANKLE INSTABILITY

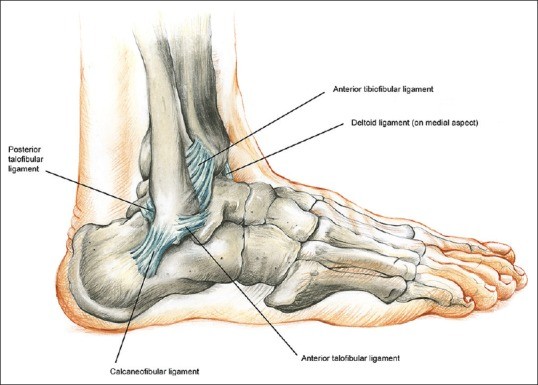

Lateral ankle sprains, the most common type, frequently involve injury to the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL). This is because the ATFL is anatomically positioned and structurally the weakest of the lateral ligaments.

Figure 1.

The lateral ligamentous components of the ankle joint, illustrating the ATFL, CFL, and PTFL.

In contrast, the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) is stronger and larger than the ATFL, running in an oblique direction, offering more robust support. The posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL), the thickest and strongest of the three, is rarely injured due to its strength and horizontal orientation.

Chronic ankle instability is broadly categorized into two types: functional instability and mechanical instability. Functional instability is often characterized by a patient’s subjective complaints of the ankle giving way or feeling unstable, sometimes accompanied by clinical signs of laxity. Mechanical instability, on the other hand, is diagnosed based on objective findings during a physical examination, indicating structural ligamentous laxity. It’s important to note that a proper chronic ankle instability diagnosis considers both functional and mechanical aspects. When conservative treatments and physical therapy fail to improve chronic ankle instability, surgical intervention is often considered.

PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS OF CHRONIC ANKLE INSTABILITY

Patients with chronic ankle instability often have a history of recurrent ankle sprains and significant inversion injuries. They frequently report a feeling of apprehension or lack of confidence in their ankle, especially during weight-bearing activities, strenuous movements, or when walking on uneven surfaces. Many may find only partial relief from wearing ankle braces.

Chronically unstable ankles are those that fail to recover adequately within the initial 6 weeks following an acute sprain and do not regain their pre-injury mechanical and functional performance. Mechanical ankle instability is a direct result of ligament laxity, while functional ankle instability is more related to deficits in postural control, neuromuscular function, muscle weakness, and proprioception.

The International Ankle Consortium has updated the criteria for diagnosing chronic ankle instability, recognizing it as a multifaceted condition. These criteria consider factors like mechanical instability, the frequency of recurrent sprains, and the patient’s perceived instability. A thorough chronic ankle instability diagnosis must take these factors into account.

Key Components of Chronic Ankle Instability Diagnosis

A comprehensive chronic ankle instability diagnosis involves a detailed assessment that includes:

1. Patient History:

- Recurrent Sprains: A history of multiple ankle sprains is a strong indicator. Inquire about the frequency, severity, and mechanisms of previous sprains.

- Inversion Injury: Specifically ask about past inversion injuries, as these are the most common cause of lateral ligament sprains leading to CAI.

- Subjective Instability: Elicit the patient’s perception of instability. Do they feel their ankle gives way? When does this occur? How does it affect their daily activities or work?

- Functional Limitations: Understand how the ankle instability impacts their ability to walk, run, jump, and perform job-related tasks, such as moving around a garage or workshop for automotive technicians.

- Brace Use and Relief: Determine if the patient uses ankle braces and how effective they are in providing stability and reducing symptoms.

- Pain History: While instability is the primary concern, pain is often a factor. Assess the location, intensity, and nature of any pain.

2. Physical Examination:

- Visual Inspection: Observe the lower extremity for any hindfoot varus misalignment, where the heel is slightly turned inward, which can predispose to lateral ankle sprains. Also, note any midfoot cavus, a high arch condition, which can contribute to instability.

- Ligamentous Laxity Tests:

- Anterior Drawer Test: This test assesses the integrity of the ATFL. With the patient’s foot slightly plantarflexed, stabilize the tibia and fibula and pull the heel forward. Excessive anterior translation of the talus indicates ATFL laxity.

- Varus Stress Test (Talar Tilt Test): This test evaluates the CFL. With the ankle in neutral position, apply a varus stress (inward tilt) to the heel while stabilizing the lower leg. Excessive talar tilt suggests CFL laxity.

- Subtalar Joint Stability Test: Assess subtalar instability, which is often overlooked. Stabilize the tibia and calcaneus and apply inversion and eversion stresses to the subtalar joint to check for excessive motion.

- Peroneal Muscle Strength: Evaluate the strength of the peroneal muscles (peroneus longus and brevis), which are crucial dynamic stabilizers of the ankle. Weakness can contribute to functional instability.

- Hindfoot Motion: Assess the range of motion of the hindfoot, including inversion, eversion, plantarflexion, and dorsiflexion. Restricted motion can be a contributing factor or a consequence of CAI.

- Proprioception Assessment:

- Romberg’s Test: Assess proprioceptive function. Have the patient stand with feet together, first with eyes open, then with eyes closed. Observe for increased sway or loss of balance with eyes closed, which suggests impaired proprioception.

- Single Leg Stance Test: Evaluate balance and proprioception by having the patient stand on one leg (both eyes open and closed) and timing how long they can maintain balance.

- Range of Motion: Measure the range of motion at the ankle and subtalar joints. Restrictions can indicate underlying issues or contribute to instability.

- Palpation: Palpate the Achilles tendon complex for tenderness, swelling, or nodules, as Achilles tendinopathy can coexist with ankle instability.

Table 1.

The authors’ views regarding patients with lateral ankle laxity. (This table is referenced in the original article but not provided in the text. In a real-world scenario, this table would be crucial for the diagnostic process).

It’s important to remember that chronic ankle instability diagnosis is not solely based on one test but rather on a combination of patient history, physical examination findings, and functional assessments.

ASSOCIATED LESIONS IN CHRONIC ANKLE INSTABILITY

Chronic ankle instability is frequently associated with other lesions resulting from or contributing to the instability. These associated lesions don’t always occur with CAI, and when they do, they rarely all present together. Recognizing these associated lesions is crucial for accurate diagnosis and comprehensive management. Common associated lesions include:

- Chronic Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS): A condition of persistent pain, often disproportionate to the initial injury.

- Neuropraxia: Nerve injury, which can lead to pain, numbness, or weakness.

- Sinus Tarsi Syndrome: Pain and inflammation in the sinus tarsi, a space between the talus and calcaneus.

- Tendon Disorders: Peroneal tendinopathy, dislocation, or subluxation. Peroneal tendons run along the outside of the ankle and can be strained or damaged with instability.

- Impingement Syndromes: Soft tissue or bony impingement within the ankle joint, causing pain and restricted motion.

- Fractures: Small fractures, such as anterior calcaneal process, fibula, and lateral talar process fractures, that may have been missed initially or occurred with recurrent sprains.

- Loose Bodies: Small fragments of cartilage or bone floating within the joint, causing pain, clicking, or locking.

- Osteochondral Lesions of the Talar Dome or Distal Tibia (OCLs): Damage to the cartilage and underlying bone within the ankle joint.

Figure 2.

(a) Sagittal and (b) coronal views of magnetic resonance imaging showing osteochondral defects of the talus, a common associated lesion in chronic ankle instability.

Figure 3.

Peroneal tendinopathy. (a) Peroneal tenosynovitis (inflammation of the tendon sheath). (b) Longitudinal tear of the peroneal brevis tendon, both frequently seen with chronic ankle instability.

MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC ANKLE INSTABILITY

Once a chronic ankle instability diagnosis is confirmed, management strategies can be implemented. Treatment approaches are generally divided into conservative and surgical options.

Conservative Management

Non-surgical management is typically recommended as the first line of treatment for chronic ankle instability, usually for a period of at least 2 months. This approach focuses on rehabilitation, including:

- Physiotherapy: Tailored exercise programs to strengthen ankle muscles (especially peroneal muscles), improve proprioception, and restore range of motion.

- Orthotics: Ankle braces or supports can provide external stability and support during activities.

- Neuromuscular and Proprioceptive Training: Specific exercises designed to improve balance, coordination, and the body’s awareness of ankle position.

Surgical Management

If conservative management fails to provide adequate relief and ankle instability persists, surgical intervention may be necessary. Surgical procedures for chronic ankle instability generally fall into three categories:

- Anatomic Repair: Direct repair of the torn ligaments, such as the Broström procedure.

- Non-Anatomic Reconstruction: Using tendon grafts to reconstruct the lateral ligaments, often using tendons like the peroneus brevis or fascia lata.

- Anatomic Reconstruction: Reconstructing the ligaments anatomically using tendon grafts.

Figure 4.

Standard surgical approach for lateral ankle ligament repair, often used in procedures like the Broström repair.

Anatomic repairs have shown good to excellent results in about 85% of patients. However, factors such as poor tissue quality, long-standing instability, cavovarus foot deformity, and significant ligamentous laxity can reduce the success rate even with tissue grafts. In these cases, reconstructive procedures may be considered.

The Broström procedure, a common anatomic repair, involves direct repair of the ATFL and CFL. Modified Broström procedures, sometimes combined with ankle arthroscopy, have shown good outcomes for patients with chronic ankle instability and intra-articular symptoms.

Figure 5.

Primary repair in the Broström procedure. (a) Identification and suturing of the torn ligament. (b) End-to-end repair under tension to restore ligament integrity.

The Broström procedure aims to restore ankle stability, particularly by addressing the ATFL. It has a high success rate, with 85–90% of patients achieving ankle stability. Recovery typically takes 3–6 months. The Gould modification of the Broström procedure strengthens the repair using the inferior extensor retinaculum and further stabilizes the subtalar joint.

When the ATFL and CFL are significantly attenuated or damaged, anatomic reconstruction using tendon grafts is often recommended. Non-anatomic reconstruction techniques, like tenodesis using tensor fasciae latae or peroneus brevis tendon, can also be employed to stabilize the ankle. Procedures like the Watson-Jones, Chrisman-Snook, and others aim to provide stability through tendon transfers, though some may have drawbacks like altered ankle biomechanics or subtalar stiffness.

Figure 6.

Ahlgren technique: (a) Augmentation of the repair using nearby fascia tissue. (b) Interosseous suture for added strength.

Figure 7.

Non-anatomic reconstruction techniques using peroneal brevis tendon flap: (a) Watson-Jones procedure. (b) Evans procedure. (c) Chrisman-Snook procedure. (d) Colville procedure, illustrating different approaches to tendon transfer for ankle stabilization.

Arthroscopic Role in Chronic Ankle Instability

Arthroscopy plays an increasingly important role in the management of chronic ankle instability. It is valuable for addressing intra-articular conditions that often coexist with CAI, such as impingement, painful ossicles, osteochondral lesions of the talus, osteophytes, and chondromalacia. These conditions can contribute to pain and dysfunction in unstable ankles.

Arthroscopic techniques can be used to assist in ligament reconstruction, such as using a 3-portal approach for autogenous plantaris tendon graft reconstruction of the CFL and ATFL. Arthroscopic thermal capsular shrinkage may also be considered for chronic ankle instability without significant ligamentous tears. Many surgeons recommend combining arthroscopy with anatomic repair procedures like the Broström-Gould, allowing for the diagnosis and treatment of associated intra-articular lesions concurrently.

Complications of Chronic Ankle Instability Management

Postoperative complications can occur following surgical management of chronic ankle instability. Wound complications are relatively uncommon, occurring in about 4% of nonanatomic tenodesis cases and 1.6% after anatomic repair. Other potential complications include:

- Stiffness: Ankle stiffness is a common post-surgical issue.

- Recurrent Instability: Instability can recur, either early due to acute re-injury or late due to chronic minor injuries or surgical failure.

- Nerve Problems: Nerve-related issues, such as paresthesia (numbness or tingling) or neuroma formation, can occur. Nerve problems are reported more frequently with nonanatomic tenodesis (9.7%) compared to anatomic repair (3.8%) or anatomic tenodesis (1.9%).

Risk factors for surgical failure include long-standing instability, significant ligamentous laxity, and cavovarus foot deformity. Stiffness is common after both anatomic and nonanatomic reconstructions but is often manageable with physiotherapy. Overtightening during nonanatomic tenodesis can lead to loss of tibiotalar and subtalar motion and impingement. Physiotherapy is crucial for addressing stiffness and recurrent instability.

CONCLUSION

Accurate chronic ankle instability diagnosis is the cornerstone of effective management. While acute ankle sprains are typically managed conservatively, chronic ankle instability often requires surgical intervention. Associated lesions are common in CAI, and addressing these is critical for successful outcomes. Treatment strategies range from conservative rehabilitation to various surgical techniques aimed at ligament repair and reconstruction. Procedures like the Broström repair and its modifications are widely used for direct ligament repair, while tendon transfers and arthroscopic techniques offer additional options for complex cases or associated intra-articular pathology. Ultimately, a comprehensive approach to diagnosis and management is essential to restore ankle stability and function, allowing individuals to return to their desired activities, whether on the sports field or in the automotive repair shop.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to duly express their heartfelt appreciation and gratitude to Ms. Jana Elias, Cambridge School of Art (BA [Hons] Illustration, 3rd year) Cambridge, UK, for providing this manuscript with its artwork.