Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is a significant global health concern, recognized as the 16th leading cause of life years lost worldwide. For primary care clinicians, effective screening, accurate diagnosis, and diligent management of CKD are crucial steps in preventing severe health outcomes such as cardiovascular disease, end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), and premature mortality. This article provides an updated guide for primary care physicians on the contemporary approaches to CKD, emphasizing early identification, staging, and evidence-based management strategies to mitigate the burden of this widespread condition.

Understanding Chronic Kidney Disease: Definition, Prevalence, and Global Impact

Chronic Kidney Disease is defined by persistent abnormalities in kidney structure or function lasting for more than three months. These abnormalities can manifest as a decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) below 60 mL/min/1.73 m², albuminuria at or above 30 mg per 24 hours, or other markers of kidney damage. Globally, CKD affects a substantial portion of the population, ranging from 8% to 16%. The prevalence is notably higher in low- and middle-income countries. While diabetes and hypertension are leading causes in developed nations, other etiologies such as glomerulonephritis, infections, and environmental toxins play a more significant role in Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and developing countries. Genetic predispositions also contribute to CKD risk, with factors like sickle cell trait and APOL1 risk alleles being more prevalent in specific populations and increasing CKD susceptibility.

In the United States, the normal aging process includes a gradual decline in GFR, approximately 1 mL/min/1.73 m² per year. The lifetime risk of developing a GFR below 60 mL/min/1.73 m² is considerable, exceeding 50%. Early detection and intervention by primary care clinicians are paramount because progressive CKD is strongly linked to adverse health outcomes, including ESKD, cardiovascular disease, and increased mortality rates. Current clinical guidelines advocate for a risk-stratified approach to CKD evaluation and management. This review highlights contemporary risk assessment tools, such as the Kidney Failure Risk Equation (KFRE) available at https://kidneyfailurerisk.com/, and focuses on providing primary care clinicians with the essential knowledge for CKD diagnosis, assessment, and management, including appropriate referral strategies to nephrology specialists and considerations for dialysis initiation.

Diagnostic Methods for Chronic Kidney Disease

CKD diagnosis typically begins with routine laboratory testing, often as part of a serum chemistry profile and urine analysis, or it may arise as an incidental finding. Less frequently, patients might present with symptoms directly related to kidney dysfunction, such as visible hematuria, foamy urine (indicating albuminuria), nocturia, flank pain, or reduced urine output. In advanced stages, CKD can manifest with systemic symptoms like fatigue, poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, a metallic taste in the mouth, unintentional weight loss, pruritus, cognitive changes, dyspnea, or peripheral edema.

When evaluating a patient for CKD, a thorough clinical history is essential. Clinicians should inquire about symptoms suggesting systemic diseases (e.g., hemoptysis, rash, lymphadenopathy, neuropathy) or urinary tract obstruction (e.g., hesitancy, urgency, frequency, incomplete bladder emptying). Crucially, assessing risk factors for kidney disease is vital. This includes a detailed history of exposure to nephrotoxins such as NSAIDs, phosphate-based bowel preparations, herbal remedies (like those containing aristolochic acid), certain antibiotics (e.g., gentamicin), and chemotherapy agents. Other important risk factors are nephrolithiasis, recurrent urinary tract infections, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, chronic infections), family history of kidney disease, and known genetic risk factors such as sickle cell trait.

A comprehensive physical examination can offer additional diagnostic clues and should include an assessment of the patient’s volume status. Signs of volume depletion might indicate poor intake, vomiting, diarrhea, or excessive diuresis, while volume overload may be associated with heart failure, liver failure, or nephrotic syndrome. Retinal examination findings like arterial-venous nicking or retinopathy can suggest long-standing hypertension or diabetes. Carotid or abdominal bruits may point to renovascular disease. Flank pain or enlarged kidneys should raise suspicion for obstructive uropathy, nephrolithiasis, pyelonephritis, or polycystic kidney disease. Neuropathy could be due to diabetes, vasculitis, or amyloidosis. Skin findings such as rash (systemic lupus erythematosus, acute interstitial nephritis), palpable purpura (Henoch-Schonlein purpura, cryoglobulinemia, vasculitis), telangiectasias (scleroderma, Fabry disease), or extensive sclerosis (scleroderma) can be indicative of underlying systemic conditions affecting the kidneys. Patients with advanced CKD may exhibit pallor, skin excoriations, muscle wasting, asterixis, myoclonic jerks, altered mental status, and a pericardial rub.

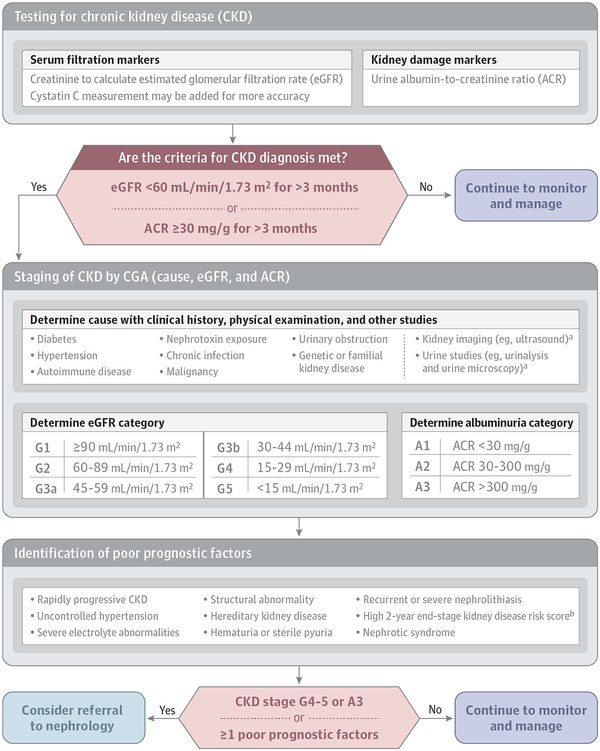

Figure 1. Diagnostic Algorithm for Chronic Kidney Disease.

Diagnostic Algorithm for Chronic Kidney Disease

Diagnostic Algorithm for Chronic Kidney Disease

Figure 1. Algorithm outlining the considerations for diagnosis, staging, and referral of patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. This includes initial assessment, GFR and albuminuria measurement, and decision points for nephrology referral. Image source: National Institutes of Health.

CKD Staging and Risk Stratification

Once CKD is diagnosed, staging is crucial for prognosis and management. CKD staging is based on GFR, albuminuria levels, and the underlying cause of kidney disease. The GFR stages range from G1 (normal or high GFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m²) to G5 (kidney failure, GFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m²). Stages G3 are further divided into G3a (GFR 45-59 mL/min/1.73 m²) and G3b (GFR 30-44 mL/min/1.73 m²). While direct GFR measurement is possible, estimated GFR (eGFR), calculated using equations like CKD-EPI, is routinely used in clinical practice. Laboratories typically report eGFR based on serum creatinine, a reliable marker of kidney function. The CKD-EPI 2009 creatinine equation is widely recommended for eGFR calculation due to its accuracy, especially at GFR values above 60 mL/min/1.73 m². Cystatin C can be used in conjunction with creatinine in the CKD-EPI 2012 equation for improved accuracy, particularly in individuals with factors affecting creatinine production.

Albuminuria staging is equally important and is classified using urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR): A1 (normal to mildly increased, ACR <30 mg/g), A2 (moderately increased, ACR 30-300 mg/g), and A3 (severely increased, ACR >300 mg/g). Urine ACR is preferred over urine protein-to-creatinine ratio due to its standardization and precision, especially at lower albumin concentrations. First morning or 24-hour urine samples provide the most accurate measurements, but random samples are acceptable for initial screening. Kidney ultrasound imaging is recommended for all CKD patients to assess kidney morphology and rule out urinary tract obstruction.

Determining the cause of CKD is essential for prognosis and treatment planning. Causes are broadly classified as systemic or localized to the kidney. Systemic causes include diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and genetic disorders, while localized causes are glomerular, tubulointerstitial, vascular, or cystic/congenital. For instance, polycystic kidney disease may progress more rapidly to ESKD and requires specific management strategies. Unexplained CKD cases warrant referral to a nephrologist for further investigation.

Figure 2. KDIGO 2012 CKD Prognosis based on GFR and Albuminuria Categories.

Figure 2. This chart illustrates the 2012 KDIGO guidelines for CKD prognosis based on GFR and albuminuria categories. Risk levels are color-coded, ranging from low (green) to very high (red), aiding in risk stratification and management planning. Source: Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO).

Screening Strategies for Early CKD Detection

Given the asymptomatic nature of early CKD in many patients, screening is vital for early detection. The National Kidney Foundation recommends a kidney profile test that includes serum creatinine for eGFR and urine ACR measurement. Risk-based screening is widely advocated, particularly for individuals over 60 years of age and those with diabetes or hypertension. Screening should also be considered for those with additional risk factors such as autoimmune diseases, obesity, kidney stones, recurrent UTIs, reduced kidney mass, exposure to nephrotoxic medications, and a history of acute kidney injury. Although no randomized trials have definitively proven that broad CKD screening improves outcomes, targeted screening of high-risk groups is a consensus recommendation.

Box 1. Risk Factors for Chronic Kidney Disease.

Clinical Risk Factors:

- Diabetes Mellitus

- Hypertension

- Autoimmune Diseases

- Systemic Infections (HIV, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C)

- Nephrotoxic Medications (NSAIDs, Lithium, Herbal Remedies)

- Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections

- Kidney Stones

- Urinary Tract Obstruction

- Malignancy

- Obesity

- Reduced Kidney Mass

- History of Acute Kidney Injury

- Smoking

- Intravenous Drug Use

- Family History of Kidney Disease

Sociodemographic Risk Factors:

- Age > 60 years

- Non-White Race

- Low Income

- Low Education Level

Genetic Risk Factors:

- APOL1 Risk Alleles

- Sickle Cell Trait and Disease

- Polycystic Kidney Disease

- Alport Syndrome

- Congenital Anomalies of the Kidney and Urinary Tract

Comprehensive Management of Chronic Kidney Disease

Management of CKD is multifaceted, focusing on slowing disease progression, managing complications, and reducing cardiovascular risk.

Reducing Cardiovascular Disease Risk

Cardiovascular disease is significantly more prevalent in CKD patients. Managing cardiovascular risk is a cornerstone of CKD care. For patients 50 years and older with CKD, statin therapy is recommended regardless of LDL cholesterol levels. Smoking cessation is also crucial. Blood pressure control is vital; guidelines generally recommend a target blood pressure of <140/90 mm Hg for most CKD patients, and <130/80 mm Hg for those with significant albuminuria (ACR ≥30 mg/g). Intensive blood pressure control (systolic BP <120 mm Hg) may provide additional cardiovascular benefits in select high-risk individuals without diabetes, although it may also increase the risk of eGFR decline.

Hypertension Management in CKD

Managing hypertension in CKD often involves renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockade with ACE inhibitors or ARBs, especially in patients with diabetes and albuminuria ≥30 mg/24 hours, or in any CKD patient with albuminuria ≥300 mg/24 hours. Dual therapy with ACE inhibitors and ARBs is generally avoided due to the risk of hyperkalemia and acute kidney injury. Aldosterone antagonists may be considered for patients with resistant hypertension, albuminuria, or heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Diabetes Management in CKD

Optimal diabetes management is critical in CKD patients. Glycemic control, aiming for a hemoglobin A1c of around 7.0%, can help slow CKD progression. Dose adjustments of oral hypoglycemic agents are frequently necessary, especially for drugs primarily cleared by the kidneys. SGLT-2 inhibitors have shown renal and cardiovascular benefits in diabetic CKD patients, particularly those with significant albuminuria, and should be considered.

Avoiding Nephrotoxins

Counseling patients to avoid nephrotoxic substances is essential. NSAIDs should be avoided in CKD, especially with ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Certain herbal remedies, phosphate-based bowel preparations, and proton pump inhibitors can also pose risks to kidney function and should be used judiciously.

Drug Dosing Adjustments in CKD

Renal function significantly impacts drug clearance. Dose adjustments are frequently required for many medications in CKD patients, including antibiotics, anticoagulants, gabapentinoids, hypoglycemic agents, and others. The CKD-EPI equation is recommended for eGFR estimation for drug dosing. Gadolinium-based contrast agents should be avoided in advanced CKD (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m²) due to the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.

Dietary Management in CKD

Dietary management in CKD is aimed at slowing progression and managing complications. Protein restriction (0.8-1.3 g/kg/day) may be recommended, particularly in later CKD stages, balancing potential benefits with the risk of malnutrition. Lower dietary acid load and sodium restriction (<2 g/day) are also generally recommended, especially for patients with hypertension, proteinuria, or fluid overload.

Monitoring CKD Progression and Complications

Regular monitoring of eGFR and albuminuria is recommended at least annually for all CKD patients, with increased frequency for higher-risk individuals. Monitoring frequency should be guided by risk stratification (Figure 2). Patients with moderate to severe CKD are at risk for complications like electrolyte imbalances, mineral and bone disorders, and anemia. Regular laboratory assessments, including complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, serum albumin, phosphate, parathyroid hormone, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and lipid panel, are necessary.

Management of Anemia in CKD

Anemia is a common CKD complication. Initial management includes assessing and correcting iron deficiency. For persistent anemia (hemoglobin <10 g/dL) despite iron repletion, referral to a nephrologist may be needed for erythropoietin-stimulating agent therapy, considering the associated risks and benefits.

Management of Electrolyte and Mineral Disorders in CKD

Electrolyte imbalances, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, and metabolic acidosis are common in CKD. Dietary modifications and supplements are often used for initial management. Oral bicarbonate supplementation may be needed for persistent metabolic acidosis (serum bicarbonate <22 mmol/L). Mineral and bone disorders are also frequent; management includes addressing hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and vitamin D deficiency with dietary phosphate restriction, phosphate binders, calcium supplementation, and vitamin D repletion as needed.

Table 1. Monitoring and Management of CKD Complications.

| Complication | Relevant Tests | Monitoring Frequency | Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anemia | Hemoglobin | No anemia: CKD G1-G2: Clinically indicated; CKD G3: ≥ annually; CKD G4-G5: ≥ twice yearly. With anemia: CKD G3-G5: every 3 months. | Rule out other causes, consider iron supplementation, nephrology referral for erythropoietin-stimulating agents if hemoglobin <10 g/dL. |

| Mineral & Bone Disorder | Calcium, Phosphate, PTH, Vit D | Calcium/Phosphate: CKD G3: 6-12 months; CKD G4: 3-6 months; CKD G5: 1-3 months. PTH: CKD G3: Baseline, then as needed; CKD G4: 6-12 months; CKD G5: 3-6 months. Vitamin D: CKD G3-G5: Baseline, then as needed. | Phosphate-lowering therapy (calcium acetate, sevelamer, iron-based binders), Vitamin D supplementation. |

| Hyperkalemia | Serum Potassium | Baseline and as needed | Low-potassium diet, correct hyperglycemia/acidemia, potassium binders. |

| Metabolic Acidosis | Serum Bicarbonate | Baseline and as needed | Oral bicarbonate supplementation for persistent bicarbonate <22 mmol/L. |

| Cardiovascular Disease | Lipid Panel | Baseline and as needed | Statin therapy for patients ≥50 years; statin for 18-49 years with CAD, diabetes, prior stroke, or high CVD risk. |

Prognosis and Risk Stratification in CKD

The risk of ESKD progression varies based on risk factors and geographic location. The Kidney Failure Risk Equation (KFRE) (https://kidneyfailurerisk.com/) is a valuable tool for predicting 2-year and 5-year ESKD risk in patients with eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m². Risk stratification helps identify high-risk individuals for closer monitoring and nephrology referral, while also reassuring low-risk patients. For patients with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m², the CKD G4+ risk calculator (https://www.kdigo.org/equation/) provides additional risk assessment for cardiovascular disease and mortality.

Referral to Nephrology and Kidney Replacement Therapy

Referral to a nephrologist is recommended when eGFR falls below 30 mL/min/1.73 m² (stage G4) or urine ACR exceeds 300 mg/24 hours (stage A3). Expedited nephrology evaluation is needed for nephrotic syndrome (albuminuria >2200 mg/24 hours). Other referral indications include unexplained hematuria, red blood cell casts, uncontrolled hypertension, persistent electrolyte abnormalities, anemia requiring erythropoietin, recurrent kidney stones, hereditary kidney disease, acute kidney injury, and rapid CKD progression (eGFR decline ≥25% or >5 mL/min/1.73 m² per year). Kidney biopsy may be indicated for unexplained albuminuria, cellular casts, or rapid GFR decline.

Kidney replacement therapy decisions are based on symptoms, not solely GFR levels. Urgent dialysis is indicated for uremic emergencies like encephalopathy or pericarditis. Elective dialysis initiation should be individualized, considering uremic symptoms, refractory electrolyte imbalances, and fluid overload. Shared decision-making is crucial, with patient education about treatment options including kidney transplantation, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and conservative care. Early referral for transplant evaluation is recommended for patients with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m² and elevated ESKD risk. Vascular access creation for hemodialysis should occur when eGFR is 15-20 mL/min/1.73 m². Patient preferences regarding dialysis modality and conservative management should be respected.

Conclusion

Chronic Kidney Disease is a widespread condition with significant morbidity and mortality. Effective diagnosis and comprehensive management by primary care clinicians are essential to reduce the global burden of CKD. Key management strategies include cardiovascular risk reduction, albuminuria treatment, nephrotoxin avoidance, appropriate drug dosing, and management of CKD complications. Early diagnosis, accurate staging, and timely nephrology referral are critical to improving outcomes for patients with CKD.

Funding/Support: (As per original article)

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: (As per original article)

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: (As per original article)

References: (To be populated with relevant, high-quality references. For now, original article references can be used and expanded.)