The American Diabetes Association (ADA) “Standards of Care in Diabetes” serves as a comprehensive guide, offering the ADA’s current clinical practice recommendations essential for diabetes management. This resource outlines the crucial components of diabetes care, encompassing general treatment objectives, evidence-based guidelines, and tools designed to assess the quality of care provided to individuals with diabetes. The ADA Professional Practice Committee, a multidisciplinary team of experts, undertakes the responsibility of annually updating these Standards of Care, and more frequently when necessary, ensuring they reflect the latest advancements in diabetes care. For an in-depth understanding of ADA standards, statements, and reports, including the evidence-grading system for ADA’s clinical practice recommendations and a comprehensive list of Professional Practice Committee members, please refer to the Introduction and Methodology. The ADA encourages feedback and invites readers to share their comments on the Standards of Care at professional.diabetes.org/SOC. This article focuses on the classification and diagnosis of diabetes, drawing from the 2023 Standards of Care to provide an updated perspective relevant to diabetes care and building upon the foundations of previous guidelines, including those from 2015.

Diabetes Classification: Understanding the Different Types

Diabetes mellitus is not a single disease but rather a group of metabolic disorders that share the common feature of hyperglycemia. The classification of diabetes is crucial as it guides diagnosis, treatment strategies, and prognosis. The ADA categorizes diabetes into four broad classes:

- Type 1 Diabetes: Primarily resulting from autoimmune destruction of pancreatic β-cells. This destruction typically leads to an absolute deficiency of insulin. Type 1 diabetes includes Latent Autoimmune Diabetes of Adulthood (LADA).

- Type 2 Diabetes: Characterized by a progressive decline in β-cell insulin secretion, often against a backdrop of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. This form is non-autoimmune.

- Specific Types of Diabetes Due to Other Causes: This category encompasses diabetes resulting from various specific conditions, including:

- Monogenic diabetes syndromes, such as neonatal diabetes and maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY).

- Diseases of the exocrine pancreas, for example, cystic fibrosis and pancreatitis.

- Drug- or chemical-induced diabetes, which can occur with glucocorticoid use, HIV/AIDS treatments, or post-organ transplantation.

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM): Defined as diabetes diagnosed during the second or third trimester of pregnancy in individuals not previously known to have diabetes before gestation.

For more detailed information, refer to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) position statement “Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus” (1).

It’s important to recognize that both type 1 and type 2 diabetes are heterogeneous conditions, presenting with a wide spectrum of clinical features and disease progression. While classification is essential for guiding therapy, it is not always straightforward to categorize individuals at the initial diagnosis. The traditional view of type 2 diabetes as an adult-onset condition and type 1 diabetes as solely affecting children is no longer accurate. Both types can occur across all age groups.

Children with type 1 diabetes often exhibit classic symptoms like polyuria (frequent urination) and polydipsia (excessive thirst), and approximately half present with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) (2–4). In adults, type 1 diabetes onset can be more varied, with symptoms potentially less pronounced than in children, and some adults may experience a temporary remission from insulin dependence (5–7). Key indicators that help distinguish type 1 diabetes include younger age at diagnosis, unintentional weight loss, ketoacidosis, and significantly elevated glucose levels (>360 mg/dL or 20 mmol/L) at presentation (8). Conversely, DKA can occasionally occur in individuals with type 2 diabetes (9,10), particularly within certain ethnic and racial minority groups (11).

Healthcare professionals must be aware that diabetes type classification can be complex at presentation, and misdiagnosis is not uncommon. For example, adults with type 1 diabetes might be initially misdiagnosed with type 2, or individuals with MODY might be mistaken for having type 1 diabetes. While distinguishing diabetes types can be challenging across all age groups at onset, the diagnosis often becomes clearer over time in individuals with β-cell deficiency as the extent of this deficiency becomes more apparent.

In both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, a combination of genetic and environmental factors can lead to the progressive loss of β-cell mass and/or function, ultimately manifesting as hyperglycemia. Once hyperglycemia develops, individuals with all forms of diabetes become susceptible to the same chronic complications, although the rate of progression can differ. Future advancements in diabetes therapy will rely on a deeper understanding of the various pathways leading to β-cell demise or dysfunction (12). Globally, researchers are actively working to integrate clinical, pathophysiological, and genetic characteristics to refine the current classification system of diabetes, aiming to move beyond the broad categories of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The goal is to create more precise diabetes subsets that enable optimized, personalized treatment strategies. Many of these ongoing studies hold significant promise and may soon contribute to a more refined diabetes classification system (13).

The underlying pathophysiology is more clearly defined in type 1 diabetes compared to type 2 diabetes. Prospective studies have established that the persistent presence of two or more islet autoantibodies is a strong predictor of developing clinical diabetes (14). The rate of progression is influenced by factors such as age at autoantibody detection, the number of autoantibodies, their specificity, and titer. Glucose and A1C levels begin to rise before the clinical onset of diabetes, allowing for diagnosis even before the onset of DKA. Type 1 diabetes can be categorized into three distinct stages, as outlined in Table 2.1, providing a framework for research and regulatory decisions (12,15).

Table 2.1. Staging of Type 1 Diabetes

FPG, fasting plasma glucose; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; 2-h PG, 2-h plasma glucose.

The classification of slowly progressive autoimmune diabetes in adults, often referred to as Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults (LADA), remains a topic of discussion, specifically whether it should be categorized as LADA or type 1 diabetes. The key clinical consideration with LADA detection is recognizing that slow autoimmune β-cell destruction can occur in adults, leading to a prolonged period of marginal insulin secretory capacity. For classification purposes, all forms of diabetes mediated by autoimmune β-cell destruction are included under type 1 diabetes. The term LADA remains clinically useful, highlighting a subset of adults likely to experience progressive autoimmune β-cell destruction (16), which may necessitate earlier insulin initiation to prevent glucose management deterioration or DKA (6,17).

The mechanisms leading to β-cell demise and dysfunction in type 2 diabetes are less well-defined. However, the common denominator appears to be deficient β-cell insulin secretion, frequently in the context of insulin resistance. Type 2 diabetes is linked to insulin secretory defects associated with genetic predisposition, inflammation, and metabolic stress. Future diabetes classification systems are expected to emphasize the underlying pathophysiology of β-cell dysfunction (12,13,18–20).

Diagnostic Tests for Diabetes: Identifying Hyperglycemia

Diagnosing diabetes relies on plasma glucose criteria, which include the fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level, the 2-hour plasma glucose (2-h PG) level during a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or A1C criteria (21). Table 2.2 outlines these diagnostic criteria.

Table 2.2. Criteria for Diabetes Diagnosis

DCCT, Diabetes Control and Complications Trial; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; NGSP, National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program; WHO, World Health Organization; 2-h PG, 2-h plasma glucose.

* In the absence of unequivocal hyperglycemia, diagnosis requires two abnormal test results from the same sample or in two separate test samples.

Generally, FPG, 2-h PG during a 75-g OGTT, and A1C are equally suitable for diagnostic screening. However, it’s important to note that the detection rates of these tests can vary across populations and individuals. Furthermore, the effectiveness of interventions for primary prevention of type 2 diabetes has primarily been demonstrated in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) with or without elevated fasting glucose, rather than in those with isolated impaired fasting glucose (IFG) or prediabetes defined by A1C criteria (22,23).

The same diagnostic tests are utilized for both screening and diagnosing diabetes, as well as for identifying individuals with prediabetes (Table 2.2 and Table 2.5) (24). Diabetes may be detected in various clinical scenarios, from routine glucose testing in seemingly low-risk individuals to screening based on diabetes risk assessments and in symptomatic patients. For comprehensive details on the evidence supporting the diagnostic criteria for diabetes, prediabetes, and abnormal glucose tolerance (IFG, IGT), refer to the ADA position statement “Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus” (1) and other reports (21,25,26).

Table 2.5. Criteria Defining Prediabetes

FPG, fasting plasma glucose; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; 2-h PG, 2-h plasma glucose.

* For all three tests, risk is continuous, extending below the lower limit of the range and becoming disproportionately greater at the higher end of the range.

Fasting and 2-Hour Plasma Glucose Tests

Both FPG and 2-h PG tests are valuable tools for diagnosing diabetes (Table 2.2). It’s important to acknowledge that the concordance between FPG and 2-h PG tests is not perfect, and similarly, there may be discordance between A1C and either glucose-based test. Compared to FPG and A1C cut-offs, the 2-h PG value tends to identify more individuals with prediabetes and diabetes (27). In cases where there is disagreement between A1C and glucose values, FPG and 2-h PG are considered more accurate (28).

A1C Test: Considerations and Recommendations

Recommendations

- 2.1a To ensure accurate diagnosis and avoid misdiagnosis, A1C testing should utilize a method certified by the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) and standardized to the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) assay. B

- 2.1b Point-of-care A1C testing for diabetes screening and diagnosis should be limited to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved devices in laboratories proficient in moderate or high complexity testing, performed by trained personnel. B

- 2.2 Significant discrepancies between measured A1C and plasma glucose levels should raise suspicion of A1C assay interference. In such cases, consider using an assay without interference or plasma blood glucose criteria for diabetes diagnosis. B

- 2.3 In conditions known to alter the relationship between A1C and glycemia, such as hemoglobinopathies (including sickle cell disease), pregnancy (second and third trimesters and postpartum period), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, HIV, hemodialysis, recent blood loss or transfusion, or erythropoietin therapy, plasma blood glucose criteria should be the sole basis for diabetes diagnosis. B

- 2.4 Ensure adequate carbohydrate intake (at least 150 g/day) for 3 days prior to oral glucose tolerance testing as a diabetes screen. A

The A1C test must be performed using an NGSP-certified method (ngsp.org) and standardized or traceable to the DCCT reference assay. FDA-approved point-of-care A1C assays, which are NGSP certified and cleared for monitoring glycemic control in people with diabetes, can be used in CLIA-regulated and CLIA-waived settings. These point-of-care tests are suitable for use in CLIA-certified, inspected laboratories or sites that meet CLIA quality standards. These standards include specific personnel qualifications (including documented annual competency assessments) and participation in an approved proficiency testing program three times per year (29–32). Point-of-care A1C assays have broader applications in clinical settings for assessing glycemic stability (as discussed in Section 6, “Glycemic Targets”).

A1C offers advantages over FPG and OGTT, including convenience (no fasting required), greater preanalytical stability, and less susceptibility to daily fluctuations due to stress, dietary changes, or illness. However, these benefits may be offset by lower sensitivity at the designated cut point, higher cost, limited availability in developing regions, and imperfect correlation with average glucose in certain individuals. Using a diagnostic threshold of ≥6.5% (48 mmol/mol), the A1C test identifies only about 30% of diabetes cases detected collectively by A1C, FPG, or 2-h PG, based on NHANES data (33). Despite these limitations, the International Expert Committee added A1C to the diagnostic criteria in 2009 to enhance screening efforts (21).

When utilizing A1C for diabetes diagnosis, it is crucial to remember that it is an indirect measure of average blood glucose levels. Factors that can affect hemoglobin glycation independently of glycemia, such as hemodialysis, pregnancy, HIV treatment (34,35), age, race/ethnicity, genetic background, and anemia/hemoglobinopathies, must be considered. (See below for further details on conditions altering the A1C-glycemia relationship.)

Age Considerations for A1C

Epidemiological studies forming the basis for A1C recommendations in diabetes diagnosis primarily involved adult populations (33). However, recent ADA guidance has concluded that A1C, FPG, or 2-h PG can be used to test for prediabetes or type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents (further details on screening and testing in children and adolescents are provided below) (36).

Race, Ethnicity, Hemoglobinopathies, and A1C

Hemoglobin variants can interfere with A1C measurements, although most assays used in the U.S. are unaffected by the most common variants. Significant discrepancies between measured A1C and plasma glucose levels should prompt consideration of A1C assay unreliability for a particular individual. For those with a hemoglobin variant but normal red blood cell turnover, like individuals with sickle cell trait, an A1C assay without hemoglobin variant interference should be used. An updated list of A1C assays with known interferences is available at ngsp.org/interf.asp.

African American individuals heterozygous for the common hemoglobin variant HbS may have A1C levels approximately 0.3% lower than those without the trait, for any given mean glycemia level (37). Another genetic variant, X-linked glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase G202A, carried by 11% of African American individuals, is associated with an A1C decrease of about 0.8% in homozygous men and 0.7% in homozygous women compared to those without the variant (38). For example, in Tanzania, where hemoglobinopathies are prevalent in people with HIV, A1C may be lower than expected based on glucose levels, limiting its screening utility (39).

Even without hemoglobin variants, A1C levels can vary with race/ethnicity independently of glycemia (40–42). For instance, African American individuals may exhibit higher A1C levels than non-Hispanic White individuals with similar fasting and post-glucose load glucose levels (43). Conflicting data exists, but African American individuals may also have higher fructosamine and glycated albumin levels and lower 1,5-anhydroglucitol levels, suggesting a potentially higher glycemic burden (especially postprandially) (44,45. Similarly, A1C levels may be higher for a given mean glucose concentration when measured by continuous glucose monitoring (46). Conversely, a recent report in Afro-Caribbean populations showed a lower A1C than predicted by glucose levels (47). Despite these reported differences, the association of A1C with complication risk appears similar in African American and non-Hispanic White populations (42,48). In the Taiwanese population, age and sex have been reported to be associated with increased A1C in men (49; however, the clinical implications of this finding are currently unclear.

Conditions Altering the A1C and Glycemia Relationship

In conditions associated with increased red blood cell turnover, such as sickle cell disease, pregnancy (second and third trimesters), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (50,51), hemodialysis, recent blood loss or transfusion, or erythropoietin therapy, plasma blood glucose criteria should be used exclusively for diabetes diagnosis (52). A1C is less reliable than blood glucose measurement in other situations, including the postpartum period (53–55), HIV treated with certain protease inhibitors (PIs) and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) (34), and iron-deficiency anemia (56).

Confirming a Diabetes Diagnosis

Unless there is a clear clinical presentation (e.g., hyperglycemic crisis or classic hyperglycemia symptoms with a random plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL [11.1 mmol/L]), a diabetes diagnosis requires two abnormal screening test results, either from the same sample (57) or from two separate test samples. If using separate samples, the second test, which can be a repeat of the initial test or a different test, should be performed promptly. For example, if an initial A1C is 7.0% (53 mmol/mol) and a repeat result is 6.8% (51 mmol/mol), diabetes diagnosis is confirmed. Similarly, if two different tests (e.g., A1C and FPG) are both above the diagnostic threshold from the same or separate samples, the diagnosis is also confirmed.

In cases of discordant results from two different tests, the test result above the diagnostic cut point should be repeated, considering potential A1C assay interference. The diagnosis is based on the confirmatory screening test. For instance, if a patient meets the A1C criterion for diabetes (two results ≥6.5% [48 mmol/mol]) but not the FPG criterion (

Each screening test has inherent preanalytical and analytical variability. Therefore, a test initially yielding an abnormal result (above the diagnostic threshold) may produce a value below the cut point upon repetition. This is more likely with FPG and 2-h PG if glucose samples are left at room temperature and not centrifuged promptly. Due to potential preanalytical variability, it’s crucial to centrifuge and separate plasma glucose samples immediately after collection. If test results are close to diagnostic thresholds, healthcare professionals should discuss symptoms with the patient and repeat testing in 3–6 months.

Individuals should consume a mixed diet containing at least 150 g of carbohydrates for 3 days before oral glucose tolerance testing (58–60). Fasting and carbohydrate restriction can falsely elevate glucose levels during an oral glucose challenge.

Diagnosis in Symptomatic Patients

In patients presenting with classic hyperglycemia symptoms, plasma glucose measurement is sufficient for diabetes diagnosis (symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis plus a random plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL [11.1 mmol/L]). In these cases, plasma glucose level is critical for confirming diabetes as the cause of symptoms and guiding management decisions. Healthcare providers may also assess A1C to determine the chronicity of hyperglycemia. The criteria for diagnosing diabetes are summarized in Table 2.2.

Type 1 Diabetes: Immune-Mediated and Idiopathic Forms

Recommendations for Type 1 Diabetes Screening

- 2.5 Screening for presymptomatic type 1 diabetes using autoantibody tests for insulin, glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), islet antigen 2, or zinc transporter 8 is currently recommended within research studies or as an option for first-degree relatives of individuals with type 1 diabetes. B

- 2.6 The development and persistence of multiple islet autoantibodies is a risk factor for clinical diabetes and may indicate intervention within clinical trials or screening for stage 2 type 1 diabetes. B

Immune-Mediated Type 1 Diabetes

This form, previously known as “insulin-dependent diabetes” or “juvenile-onset diabetes,” accounts for 5–10% of diabetes cases and results from cell-mediated autoimmune destruction of pancreatic β-cells. Autoimmune markers include islet cell autoantibodies and autoantibodies to GAD (glutamic acid decarboxylase, GAD65), insulin, tyrosine phosphatases islet antigen 2 (IA-2) and IA-2β, and zinc transporter 8. Numerous clinical trials are underway to evaluate various methods for preventing type 1 diabetes in individuals with evidence of islet autoimmunity (trialnet.org/our-research/prevention-studies) (14,17,61–64). Stage 1 type 1 diabetes is defined by the presence of two or more of these autoimmune markers. The disease has strong HLA associations, particularly with the DQB1 and DRB1 haplotypes, and genetic screening has been used in research to identify high-risk populations. Specific alleles within these genes can be either predisposing or protective (Table 2.1).

The rate of β-cell destruction varies significantly, being rapid in some individuals (especially infants and children) and slower in others (mainly adults) (65,66). Children and adolescents often present with DKA as the initial symptom, and rates in the U.S. have increased dramatically in the past 20 years (2–4). Others may have mild fasting hyperglycemia that can quickly progress to severe hyperglycemia and/or DKA with infection or stress. Adults may retain sufficient β-cell function to prevent DKA for many years. These individuals may experience remission or reduced insulin needs for months or years before becoming insulin-dependent and at risk for DKA (5–7,67,68). In the later stages, there is minimal to no insulin secretion, evidenced by low or undetectable plasma C-peptide levels. Immune-mediated diabetes is the most common diabetes form in childhood and adolescence, but it can occur at any age.

Autoimmune β-cell destruction involves multiple genetic and environmental factors, which are still not fully understood. While individuals with type 1 diabetes typically are not obese at presentation, obesity is increasingly common in the general population and should not preclude type 1 diabetes testing. People with type 1 diabetes are also more susceptible to other autoimmune disorders, such as Hashimoto thyroiditis, Graves disease, celiac disease, Addison disease, vitiligo, autoimmune hepatitis, myasthenia gravis, and pernicious anemia (see Section 4, “Comprehensive Medical Evaluation and Assessment of Comorbidities”). Type 1 diabetes can be associated with monogenic polyglandular autoimmune syndromes, including immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, and X-linked (IPEX) syndrome, caused by FOXP3 gene mutation, and another syndrome caused by AIRE gene mutation (69,70).

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment has led to unexpected autoimmune adverse events, including fulminant onset of type 1 diabetes with DKA and low/undetectable C-peptide levels (71,72). Fewer than half of these patients have typical type 1 diabetes autoantibodies, suggesting alternate pathobiology. This immune-related adverse event occurs in just under 1% of checkpoint inhibitor-treated patients, most commonly with programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 pathway blockers, alone or in combination (73). To date, most immune checkpoint inhibitor–related type 1 diabetes cases occur in people with high-risk HLA-DR4 (present in 76% of patients), while other high-risk HLA alleles are not more common than in the general population (73). Currently, risk cannot be predicted by family history or autoantibodies, so healthcare professionals administering these medications should be aware of this adverse effect and educate patients accordingly.

Idiopathic Type 1 Diabetes

Some type 1 diabetes forms have unknown etiologies. These individuals experience permanent insulinopenia and are prone to DKA but lack β-cell autoimmunity evidence. However, only a small minority of type 1 diabetes cases fall into this category. Individuals with autoantibody-negative type 1 diabetes of African or Asian ancestry may experience episodic DKA with varying insulin deficiency between episodes (possibly ketosis-prone diabetes) (74). This form is strongly inherited and not HLA-associated. Insulin replacement therapy needs may be intermittent. Further research is needed to determine the cause of β-cell destruction in this rare clinical scenario.

Screening for Type 1 Diabetes Risk

The incidence and prevalence of type 1 diabetes are increasing (75). Individuals with type 1 diabetes often present with acute diabetes symptoms and markedly elevated blood glucose levels, with 40–60% diagnosed with life-threatening DKA (2–4). Studies indicate that measuring islet autoantibodies in relatives of type 1 diabetes patients (15) or in children from the general population (76,77) can effectively identify those who will develop type 1 diabetes. A study reported that of 585 children with more than two autoantibodies, nearly 70% developed type 1 diabetes within 10 years and 84% within 15 years (14. The risk of type 1 diabetes increases with the number of detected autoantibodies (63,78,79). In the TEDDY study, type 1 diabetes developed in 21% of 363 subjects with at least one autoantibody by age 3 (80). Such testing, coupled with diabetes symptom education and close follow-up, enables earlier diagnosis and DKA prevention (81,82).

While widespread clinical screening of asymptomatic low-risk individuals is not currently recommended due to a lack of approved therapeutic interventions, several innovative research screening programs exist in Europe (e.g., Fr1da, gppad.org) and the U.S. (trialnet.org, askhealth.org). Participation in these programs should be encouraged to accelerate the development of evidence-based clinical guidelines for the general population and relatives of those with type 1 diabetes. Individuals testing positive should receive counseling about diabetes risk, symptoms, and DKA prevention. Numerous clinical studies are testing methods to prevent and treat stage 2 type 1 diabetes with promising results (see clinicaltrials.gov and trialnet.org). Teplizumab, an anti-CD3 antibody, has shown promise in delaying overt diabetes development in at-risk relatives in a randomized controlled trial (83,84). This agent has been submitted to the FDA for delaying or preventing clinical type 1 diabetes in at-risk individuals, but neither this nor other agents in this category are currently available for clinical use.

Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes: Screening and Diagnosis

Recommendations for Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes Screening

- 2.7 Screen asymptomatic adults for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes using an informal risk factor assessment or validated risk calculator. B

- 2.8 Consider testing asymptomatic adults of any age with overweight or obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2 or ≥23 kg/m2 in Asian American individuals) who have one or more risk factors (Table 2.3) for prediabetes and/or type 2 diabetes. B

- 2.9 For all individuals, screening should begin at age 35 years. B

- 2.10 If tests are normal, repeat screening is recommended at least every 3 years, or sooner with symptoms or risk changes (e.g., weight gain). C

- 2.11 FPG, 2-h PG during 75-g OGTT, and A1C are all appropriate for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes screening (Table 2.2 and Table 2.5). B

- 2.12 When using OGTT for diabetes screening, ensure adequate carbohydrate intake (at least 150 g/day) for 3 days before testing. A

- 2.13 Identify and treat cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. A

- 2.14 Consider risk-based screening for prediabetes and/or type 2 diabetes after puberty onset or after age 10 (whichever is earlier) in children and adolescents with overweight (BMI ≥85th percentile) or obesity (BMI ≥95th percentile) and one or more diabetes risk factors (Table 2.4). B

- 2.15 Screen people with HIV for diabetes and prediabetes with a fasting glucose test before starting antiretroviral therapy, at therapy switching, and 3–6 months post-initiation or switching. If initial results are normal, check fasting glucose annually. E

Table 2.3. Criteria for Diabetes or Prediabetes Screening in Asymptomatic Adults

CVD, cardiovascular disease; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance.

Table 2.4. Risk-Based Screening for Type 2 Diabetes or Prediabetes in Asymptomatic Children and Adolescents

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus.

* After the onset of puberty or after 10 years of age, whichever occurs earlier. If tests are normal, repeat testing at a minimum of 3-year intervals (or more frequently if BMI is increasing or risk factor profile deteriorating) is recommended. Reports of type 2 diabetes before age 10 years exist, and this can be considered with numerous risk factors.

Prediabetes: A High-Risk State

“Prediabetes” refers to individuals with glucose levels not meeting diabetes criteria but exhibiting abnormal carbohydrate metabolism (48,85). Prediabetes is defined by IFG, IGT, and/or A1C of 5.7–6.4% (39–47 mmol/mol) (Table 2.5). It is not a clinical entity itself, but a risk factor for diabetes progression and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Screening criteria for diabetes or prediabetes in asymptomatic adults are in Table 2.3. Prediabetes is associated with obesity (especially abdominal or visceral obesity), dyslipidemia, and hypertension, necessitating comprehensive cardiovascular risk factor screening.

Prediabetes Diagnosis

IFG is defined as FPG levels of 100–125 mg/dL (5.6–6.9 mmol/L) (82,83), and IGT as 2-h PG levels during a 75-g OGTT of 140–199 mg/dL (7.8–11.0 mmol/L) (25). The WHO and other diabetes organizations define the IFG lower limit at 110 mg/dL (6.1 mmol/L).

Prospective studies using A1C to predict diabetes progression demonstrate a strong, continuous association between A1C and subsequent diabetes. A systematic review showed that individuals with A1C between 5.5% and 6.0% (37–42 mmol/mol) had a significantly increased diabetes risk (5-year incidence 9–25%). Those with A1C 6.0–6.5% (42–48 mmol/mol) had a 5-year diabetes risk of 25–50% and a 20-fold higher relative risk compared to A1C of 5.0% (31 mmol/mol) (86). A community-based study found baseline A1C a stronger predictor of diabetes and CVD events than fasting glucose (87). A1C of 5.7% (39 mmol/mol) or higher indicates a diabetes risk similar to high-risk DPP participants (88), and baseline A1C was a strong predictor of glucose-defined diabetes during the DPP follow-up (89).

Therefore, A1C 5.7–6.4% (39–47 mmol/mol) is a reasonable range for identifying prediabetes. Individuals with IFG, IGT, or A1C 5.7–6.4% (39–47 mmol/mol) should be informed of increased diabetes and CVD risk and counseled on risk reduction strategies (see Section 3, “Prevention or Delay of Type 2 Diabetes and Associated Comorbidities”). Diabetes risk rises disproportionately with increasing A1C (86), necessitating aggressive interventions and vigilant follow-up for those at very high risk (e.g., A1C >6.0% [42 mmol/mol]).

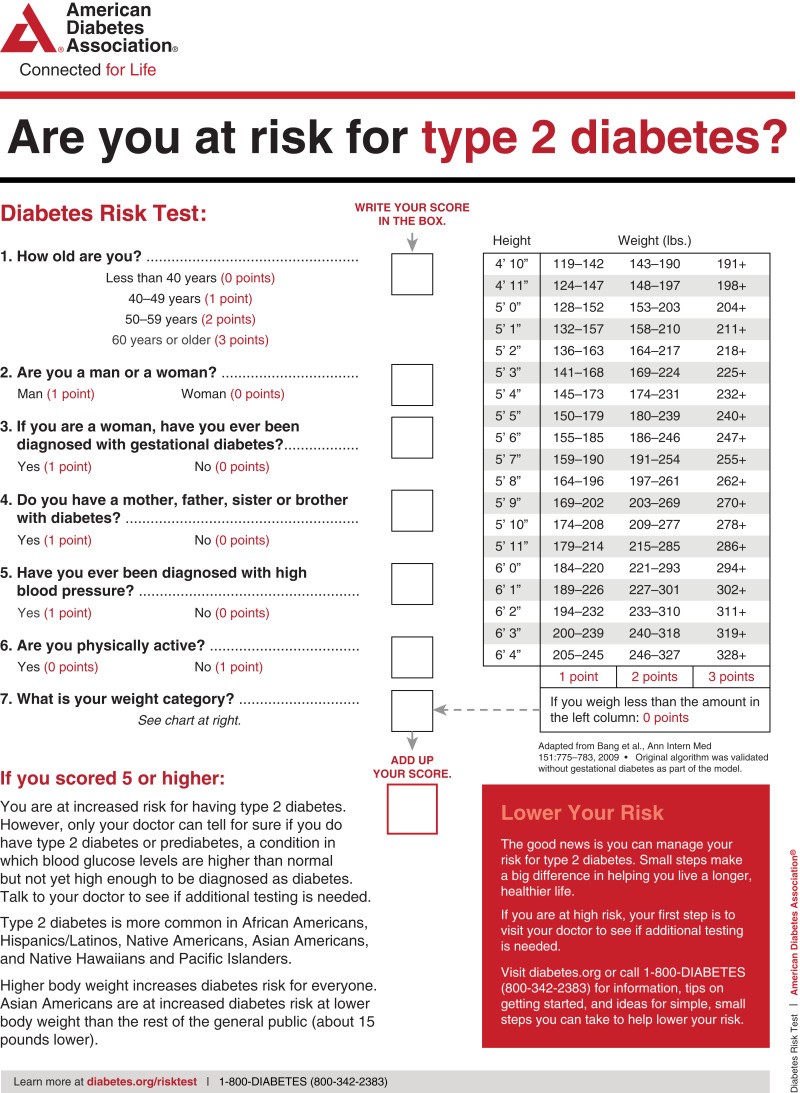

Table 2.5 summarizes prediabetes categories, and Table 2.3 outlines prediabetes screening criteria. The ADA Diabetes Risk Test (Figure 2.1) is another option for assessing the need for diabetes or prediabetes screening in asymptomatic adults (diabetes.org/socrisktest). For details on risk factors and prediabetes screening, see sections on screening in asymptomatic adults and children/adolescents below. For individuals with prediabetes most likely to benefit from lifestyle interventions, see Section 3, “Prevention or Delay of Type 2 Diabetes and Associated Comorbidities.”

Figure 2.1. ADA Diabetes Risk Test

Figure 2.1: ADA Diabetes Risk Test questionnaire for assessing risk of type 2 diabetes.

Figure 2.1: ADA Diabetes Risk Test questionnaire for assessing risk of type 2 diabetes.

ADA risk test (diabetes.org/socrisktest).

Type 2 Diabetes: The Most Common Form

Type 2 diabetes, previously known as “non-insulin-dependent diabetes” or “adult-onset diabetes,” accounts for 90–95% of all diabetes cases. It involves relative insulin deficiency and peripheral insulin resistance. Initially and often throughout life, individuals may not require insulin for survival.

Type 2 diabetes has various causes, but autoimmune β-cell destruction is not involved, and known diabetes causes are absent. Most, but not all, individuals with type 2 diabetes are overweight or obese. Excess weight contributes to insulin resistance. Even those not obese by traditional criteria may have increased abdominal fat.

DKA rarely occurs spontaneously in type 2 diabetes, typically arising with stress from illness or certain drugs (90,91). Type 2 diabetes often goes undiagnosed for years due to gradual hyperglycemia development and often subtle early symptoms. However, undiagnosed individuals are still at risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications.

People with type 2 diabetes may have normal or elevated insulin levels, but blood glucose normalization fails due to defective glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and insulin resistance. Insulin resistance can improve with weight reduction, physical activity, and/or medication, but is rarely fully restored. Recent interventions with intensive lifestyle changes or bariatric surgery have led to diabetes remission (92–98) (see Section 8, “Obesity and Weight Management for the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes”).

Type 2 diabetes risk increases with age, obesity, and physical inactivity (99,100), and is more frequent in individuals with prior GDM or polycystic ovary syndrome. It is also more common in those with hypertension, dyslipidemia, and certain racial/ethnic subgroups. A strong genetic predisposition or family history is often present. However, type 2 diabetes genetics are complex and under investigation in precision medicine (18). In younger adults without traditional risk factors, consider islet autoantibody testing to rule out type 1 diabetes (8).

Screening and Testing for Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes in Asymptomatic Adults

Screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes risk using risk factor assessments (Table 2.3) or tools like the ADA risk test (Figure 2.1) (diabetes.org/socrisktest) is recommended to guide healthcare professionals on whether diagnostic testing (Table 2.2) is needed. Early detection of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes through screening is crucial due to their prevalence and significant health burden. There is a long presymptomatic phase in type 2 diabetes. Simple detection tests are available (101). Glycemic burden duration is a strong predictor of adverse outcomes. Effective interventions exist to prevent prediabetes progression to diabetes. Individualizing risk/benefit for prediabetes intervention and considering patient-centered goals is important, with risk models suggesting higher intervention benefit in those at highest risk (102) (see Section 3, “Prevention or Delay of Type 2 Diabetes and Associated Comorbidities”) and reduced diabetes complication risk (103) (see Sections 10-12). The DPPOS showed that preventing prediabetes progression to diabetes (104) lowered retinopathy and nephropathy rates (105). Similar impacts on diabetes complications were reported with screening, diagnosis, and risk factor management in the U.K. (103).

Approximately one-quarter of people with diabetes in the U.S. and nearly half of Asian and Hispanic Americans with diabetes are undiagnosed (106,107). While screening asymptomatic individuals may seem reasonable, rigorous clinical trials proving its effectiveness are lacking. Clinical conditions like hypertension and obesity enhance risk (108). Diabetes in women of childbearing age is underdiagnosed (109). Probabilistic modeling suggests cost and health benefits of preconception screening (110).

A European randomized controlled trial compared diabetes screening and intensive multifactorial intervention to screening and routine care (111). After 5.3 years, intensive treatment modestly improved CVD risk factors compared to routine care, but CVD event/mortality incidence was not significantly different (26). Excellent routine care and lack of an unscreened control limited determining if screening and early treatment improved outcomes versus no screening and later treatment. Simulation modeling suggests major benefits from early diagnosis and treatment of hyperglycemia and CVD risk factors in type 2 diabetes (112); screening from age 30 or 45, regardless of risk factors, may be cost-effective (113), reinforced by cohort studies (114,115).

Additional considerations for type 2 diabetes and prediabetes testing in asymptomatic individuals include:

Age and Screening

Age is a major diabetes risk factor. Testing should start by age 35 for all individuals (116). Consider screening adults of any age with overweight/obesity and diabetes risk factors.

BMI and Ethnicity Considerations

BMI ≥25 kg/m2 is generally a diabetes risk factor. However, a lower BMI cut point is suggested for Asian Americans (117,118). A BMI of 23–24 kg/m2 has 80% sensitivity for Asian American subgroups, making 23 kg/m2 a practical rounded cut point. WHO data also suggest BMI ≥23 kg/m2 for increased risk in Asian Americans (119). Undiagnosed diabetes in one-third to one-half of Asian Americans suggests insufficient testing at lower BMI thresholds (99,120).

Evidence also suggests lower BMI cut points may benefit other populations. For example, a BMI of 30 kg/m2 in non-Hispanic Whites is equivalent to 26 kg/m2 in African Americans for similar diabetes incidence (121).

Medications and Diabetes Risk

Certain medications, like glucocorticoids and atypical antipsychotics (92), increase diabetes risk and should be considered when deciding to screen.

HIV and Diabetes Screening

Individuals with HIV are at higher risk of prediabetes and diabetes on antiretroviral therapies, necessitating screening (122). A1C may underestimate glycemia in HIV and is not recommended for diagnosis or monitoring (35). Weight loss through lifestyle modifications may reduce diabetes progression in prediabetes. Preventive care for HIV-associated diabetes is critical to reduce microvascular and macrovascular complication risks. Diabetes risk is increased with certain PIs and NRTIs. New-onset diabetes occurs in >5% of HIV patients on PIs, and >15% may have prediabetes (123).

PIs are associated with insulin resistance and β-cell apoptosis. NRTIs affect fat distribution, linked to insulin resistance. Discontinuing problematic ARVs may be considered if safe alternatives exist (124, carefully considering HIV control and new ARV agent adverse effects. Antihyperglycemic agents may still be necessary.

Testing Interval

The optimal screening test interval is unknown (125). A 3-year interval is suggested to reduce false positives and ensure retesting before substantial time elapses and complications develop (125). Shorter intervals may be useful in high-risk individuals, particularly with weight gain.

Community Screening Considerations

Ideally, screening should occur in healthcare settings due to the need for follow-up and treatment. Community screening outside healthcare settings is generally not recommended due to potential lack of follow-up. However, community screening may be considered with established referral systems for positive tests. Community screening may also be poorly targeted, missing high-risk groups and testing low-risk or already diagnosed individuals (126).

Screening in Dental Practices

Periodontal disease association with diabetes has prompted exploration of dental practice screening and referral to primary care for improved prediabetes and diabetes diagnosis (127–129). One study estimated 30% of dental patients ≥30 years had dysglycemia (129,130). Further research is needed on feasibility, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of dental setting screening.

Screening and Testing in Children and Adolescents

Type 2 diabetes incidence and prevalence in children and adolescents have dramatically increased, especially in minority populations (75). See Table 2.4 for risk-based screening recommendations in children and adolescents (36). Diagnostic criteria for diabetes and prediabetes (Table 2.2 and Table 2.5) apply to children, adolescents, and adults. See Section 14, “Children and Adolescents,” for more on type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents.

Some studies question A1C validity in pediatrics, particularly in certain ethnicities, suggesting OGTT or FPG as better diagnostic tests (131). However, diabetes diagnostic criteria are based on long-term health outcomes, and pediatric validations are lacking (132). The ADA acknowledges limited data supporting A1C for type 2 diabetes diagnosis in children and adolescents. While A1C is not recommended for diagnosing diabetes in children with cystic fibrosis or suspected type 1 diabetes, and only interference-free A1C assays are suitable for children with hemoglobinopathies, the ADA recommends A1C and Table 2.2 criteria for type 2 diabetes diagnosis in this cohort to reduce screening barriers (133,134).

Cystic Fibrosis–Related Diabetes (CFRD)

Recommendations for CFRD Screening and Management

- 2.16 Annual OGTT screening for CFRD should begin by age 10 in all individuals with cystic fibrosis not previously diagnosed with CFRD. B

- 2.17 A1C is not recommended as a CFRD screening test. B

- 2.18 Insulin is the recommended treatment for CFRD to achieve individualized glycemic goals. A

- 2.19 Annual monitoring for diabetes complications is recommended starting 5 years after CFRD diagnosis. E

CFRD is the most common comorbidity in cystic fibrosis, affecting about 20% of adolescents and 40–50% of adults (135). CFRD is associated with worse nutritional status, more severe lung disease, and higher mortality compared to type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Insulin insufficiency is the primary defect in CFRD. Genetic β-cell function and infection/inflammation-related insulin resistance may also contribute. Milder glucose tolerance abnormalities are even more common and occur earlier than CFRD. Whether IGT should be treated with insulin is undetermined. Screening before age 10 can identify CFRD progression risk in those with abnormal glucose tolerance, but no benefit has been established for weight, height, BMI, or lung function. OGTT is the recommended screening test. Recent publications suggest a 5.5% A1C cut point (5.8% in another study) could detect >90% of cases and reduce screening burden (136,137). Ongoing studies are validating this approach, but A1C is not currently recommended for screening (138). Weight loss or failure to gain weight is a CFRD risk and should prompt screening (136,137). The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry (139) diagnosed 13% of 3,553 people with cystic fibrosis with CFRD. Early CFRD diagnosis and treatment were associated with lung function preservation. The European Cystic Fibrosis Society Patient Registry reported increasing CFRD with age, genotype, decreased lung function, and female sex (140,141). Continuous glucose monitoring or HOMA of β-cell function (142) may be more sensitive than OGTT for CFRD progression risk, but evidence linking these results to long-term outcomes is lacking, and these tests are not recommended for screening outside of research (143).

CFRD mortality has significantly decreased, and the mortality gap between cystic fibrosis patients with and without diabetes has narrowed (144). Clinical trial data on CFRD therapy is limited. The largest study compared premeal insulin aspart, repaglinide, or placebo in cystic fibrosis patients with diabetes or abnormal glucose tolerance. Insulin-treated patients reversed weight loss, gaining 0.39 BMI units (P = 0.02). Repaglinide showed initial weight gain but not sustained at 6 months. Placebo patients continued weight loss (144). Insulin remains the most common CFRD therapy (145, primarily to induce an anabolic state and promote macronutrient retention and weight gain.

Additional CFRD management resources include the ADA/Cystic Fibrosis Foundation guidelines (146) and the ISPAD 2018 guidelines (135).

Posttransplantation Diabetes Mellitus (PTDM)

Recommendations for PTDM Screening and Management

- 2.20 Screen for hyperglycemia after organ transplantation. Formal PTDM diagnosis is best made once the individual is stable on immunosuppression and without acute infection. B

- 2.21 OGTT is the preferred test for PTDM diagnosis. B

- 2.22 Immunosuppressive regimens for optimal patient and graft survival should be used, regardless of PTDM risk. E

PTDM, or NODAT (new-onset diabetes after transplantation), describes diabetes development post-transplant (147). It excludes pre-transplant diabetes and transient post-transplant hyperglycemia (148). Hyperglycemia is common early post-transplant, with ~90% of kidney recipients exhibiting it in the first weeks (148–151). Most stress- or steroid-induced hyperglycemia resolves by discharge (151,152). Immunosuppression is a major PTDM contributor, but transplant rejection risks outweigh PTDM risks. Diabetes care professionals should treat hyperglycemia regardless of immunosuppression type (148). PTDM risk factors include general diabetes risks and transplant-specific factors like immunosuppressants (153–155). Formal PTDM diagnosis is best made when the patient is stable on maintenance immunosuppression and without acute infection (151–153,156. In a heart transplant study, 38% had PTDM at 1 year (157. OGTT is the gold standard for PTDM diagnosis (1 year post-transplant) (148,149,159,160. Screening with fasting glucose and/or A1C can identify high-risk individuals for further OGTT assessment.

Few randomized controlled studies have reported on PTDM antihyperglycemic agents (153,163,164). PTDM patients have higher rejection, infection, and rehospitalization rates (151,153,165). Insulin is the preferred agent for hyperglycemia, PTDM, and pre-existing diabetes in the hospital setting. Post-discharge, patients with pre-existing diabetes can resume their pre-transplant regimen if well-controlled. Those with poor glycemic stability or persistent hyperglycemia should continue insulin with home glucose monitoring to adjust doses and potentially switch to noninsulin agents.

No studies have established the safest or most effective noninsulin agents for PTDM. Agent choice is based on side effect profiles and interactions with immunosuppression regimens (153). Dose adjustments may be needed due to decreased glomerular filtration rate, common in transplant patients. Metformin was safe in a small renal transplant recipient study (166), but safety in other transplants is undetermined. Thiazolidinediones have been used in liver and kidney transplants, but side effects include fluid retention and heart failure (167,168). DPP-4 inhibitors do not interact with immunosuppressants and have shown safety in small trials (169,170. Well-designed trials of antihyperglycemic agent efficacy and safety in PTDM are needed.

Monogenic Diabetes Syndromes: Neonatal Diabetes and MODY

Recommendations for Monogenic Diabetes Testing

- 2.23 Genetic testing for neonatal diabetes is immediately recommended for all individuals diagnosed with diabetes in the first 6 months of life, regardless of current age. A

- 2.24 Genetic testing for MODY is recommended for children and young adults without typical type 1 or type 2 diabetes characteristics, often with a family history of diabetes in successive generations (suggestive of autosomal dominant inheritance). A

- 2.25 Consultation with a center specializing in diabetes genetics is recommended to understand genetic mutation significance and guide further evaluation, treatment, and genetic counseling. E

Monogenic defects causing β-cell dysfunction, like neonatal diabetes and MODY, represent a small fraction of diabetes cases (Table 2.6 lists common causes. For a comprehensive list, see Genetic Diagnosis of Endocrine Disorders (171).

Table 2.6. Common Causes of Monogenic Diabetes

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; UPD6, uniparental disomy of chromosome 6; 2-h PG, 2-h plasma glucose.

Neonatal Diabetes: Diagnosis and Genetic Testing

Diabetes before 6 months of age is termed “neonatal” or “congenital” diabetes. About 80–85% have a monogenic cause (8,172–175. Neonatal diabetes after 6 months is less common, while autoimmune type 1 diabetes is rare before 6 months. Neonatal diabetes can be transient or permanent. Transient diabetes is often due to chromosome 6q24 gene overexpression and may be treatable with non-insulin medications. Permanent neonatal diabetes is commonly caused by autosomal dominant mutations in KCNJ11 and ABCC8 genes. A recent report details a EIF2B1 mutation associated with permanent neonatal diabetes and hepatic dysfunction (176). The ADA-EASD type 1 diabetes consensus recommends genetic testing for individuals diagnosed under 6 months, regardless of current age (8). Correct diagnosis is critical as 30–50% of KATP-related neonatal diabetes patients improve on high-dose sulfonylureas instead of insulin. Insulin gene (INS) mutations are the second most common cause of permanent neonatal diabetes, and while intensive insulin management is preferred, genetic counseling is important due to dominant inheritance patterns.

Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY)

MODY is characterized by early-onset hyperglycemia (classically <25 years, but diagnosis can be later). It involves impaired insulin secretion with minimal insulin action defects (absent coexisting obesity). It is autosomal dominantly inherited, with abnormalities in at least 13 genes identified (177). Common forms are GCK-MODY (MODY2), HNF1A-MODY (MODY3), and HNF4A-MODY (MODY1).

MODY treatment implications warrant genetic testing (178,179). GCK-MODY patients have mild, stable fasting hyperglycemia, not usually requiring antihyperglycemic therapy except during pregnancy. HNF1A- or HNF4A-MODY patients respond well to low-dose sulfonylureas, first-line therapy; insulin may be needed over time. HNF1B mutations/deletions are associated with renal cysts and uterine malformations (RCAD syndrome). Other rare MODY forms involve transcription factor genes like PDX1 (IPF1) and NEUROD1.

Monogenic Diabetes Diagnosis

Diagnosing common MODY forms (HFN1A-MODY, GCK-MODY, HNF4A-MODY) allows for cost-effective therapy (no therapy for GCK-MODY; sulfonylureas for HNF1A/4A-MODY). Diagnosis also helps identify affected family members. Genetic screening is increasingly available and cost-effective (176,178.

MODY diagnosis should be considered in atypical diabetes cases with multiple family members with diabetes not typical of type 1 or type 2, though “atypical diabetes” is increasingly hard to define precisely without definitive type-specific tests (173–175,178–184). Type 1 diabetes autoantibody presence usually precludes monogenic diabetes testing, but autoantibodies in monogenic diabetes have been reported (185). Suspected monogenic diabetes cases should be referred to a specialist or consulted with specialized centers. Readily available commercial genetic testing, supported by insurance, is now cost-effective and increasingly accessible (186). Biomarker screening like urinary C-peptide/creatinine ratio and antibody screening may help identify who needs MODY genetic testing (187). Correct diagnosis is critical to avoid misdiagnosis as type 1 or type 2 diabetes, leading to suboptimal treatment and delayed family member diagnoses (188. Correct diagnosis is crucial for GCK-MODY, where studies show no complications without glucose-lowering therapy (189). HNFIA- and HNF4A-MODY complication risks are similar to type 1 and type 2 diabetes (190,191. Genetic counseling is recommended for inheritance patterns and comprehensive cardiovascular risk management.

Monogenic diabetes diagnosis should be considered in children and adults with early adulthood diabetes and:

- Diabetes diagnosed within the first 6 months of life (INS and ABCC8 mutations may present later) (172,192)

- Diabetes without typical type 1 or type 2 features (negative autoantibodies, no obesity, lacking metabolic features, strong family history)

- Stable, mild fasting hyperglycemia (100–150 mg/dL [5.5–8.5 mmol/L]), stable A1C 5.6–7.6% (38–60 mmol/mol), especially without obesity.

Pancreatic Diabetes (Type 3c Diabetes)

Pancreatic diabetes includes structural and functional loss of insulin secretion due to exocrine pancreatic dysfunction, often misdiagnosed as type 2 diabetes. Termed “type 3c diabetes” or pancreoprivic diabetes (1), etiologies include pancreatitis, trauma, pancreatectomy, neoplasia, cystic fibrosis, hemochromatosis, and rare genetic disorders (193). Pancreatitis, even a single episode, can lead to postpancreatitis diabetes mellitus (PPDM). Risk is highest with recurrent pancreatitis. Distinguishing features are pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, pathological pancreatic imaging, and no type 1 diabetes autoimmunity (194–199). There is loss of both insulin and glucagon secretion and often higher insulin requirements. Microvascular complication risk is similar to other diabetes forms. Pancreatectomy may involve islet autotransplantation to retain insulin secretion (200,201, potentially leading to insulin independence or reduced insulin needs (202).

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM)

Recommendations for GDM Screening and Management

- 2.26a Screen individuals planning pregnancy with risk factors B and consider testing all individuals of childbearing potential for undiagnosed diabetes. E

- 2.26b Test individuals with risk factors before 15 weeks of gestation B and consider testing all individuals E for undiagnosed diabetes at the first prenatal visit using standard diagnostic criteria if not screened preconception.

- 2.26c Treat individuals of childbearing potential identified with diabetes accordingly. A

- 2.26d Screen for early abnormal glucose metabolism before 15 weeks of gestation to identify individuals at higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, insulin need, and later GDM diagnosis. B Treatment may provide some benefit. E

- 2.26e Screen for early abnormal glucose metabolism using fasting glucose 110–125 mg/dL (6.1 mmol/L) or A1C 5.9–6.4% (41–47 mmol/mol). B

- 2.27 Screen for GDM at 24–28 weeks of gestation in pregnant individuals not previously diagnosed with diabetes or high-risk abnormal glucose metabolism detected earlier. A

- 2.28 Screen individuals with GDM for prediabetes or diabetes at 4–12 weeks postpartum using 75-g OGTT and nonpregnancy diagnostic criteria. B

- 2.29 Lifelong screening for diabetes or prediabetes at least every 3 years is recommended for individuals with GDM history. B

- 2.30 Individuals with GDM history and prediabetes should receive lifestyle interventions and/or metformin to prevent diabetes. A

GDM Definition and Early Screening

GDM was previously defined as any glucose intolerance first recognized during pregnancy (86). This definition facilitated detection and classification but has limitations (203). Evidence suggests many GDM cases are pre-existing hyperglycemia detected by routine pregnancy screening, as routine screening is not common in nonpregnant individuals of reproductive age. Hyperglycemia severity is clinically important for maternal and fetal risks.

Obesity and diabetes epidemics have increased type 2 diabetes in reproductive-age individuals, increasing pregnant individuals with undiagnosed type 2 diabetes early in pregnancy (204–206). Undiagnosed diabetes should ideally be identified preconception in at-risk individuals or populations (207–212). Preconception care for pre-existing diabetes reduces A1C and birth defect risk (213). If not screened preconception, universal early screening at Table 2.3 is needed, especially in high-risk populations with undiagnosed diabetes in childbearing age. Racial and ethnic disparities exist in undiagnosed diabetes prevalence. Early screening identifies health disparities (209–212). Standard diagnostic criteria for undiagnosed diabetes in early pregnancy are the same as for nonpregnant populations (Table 2.2). Individuals with diabetes by standard criteria should be classified as having diabetes complicating pregnancy (usually type 2) and managed accordingly.

Early abnormal glucose metabolism (fasting glucose ≥110 mg/dL or A1C ≥5.9%) may identify individuals at higher risk of adverse outcomes, insulin need, and later GDM diagnosis (214–220. A1C ≥5.7% has not been shown to be associated with adverse perinatal outcomes (221,222).

If early screening is negative, rescreen for GDM at 24–28 weeks gestation (see Section 15, “Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy”). IADPSG GDM diagnostic criteria for 75-g OGTT and two-step criteria should not be used for early screening as they were not derived from first-half pregnancy data (223). Benefits of treating early abnormal glucose metabolism are uncertain. Nutrition counseling and weekly “block” glucose testing are suggested. Daily testing and intensified treatment may be needed if fasting glucose is predominantly >110 mg/dL before 18 weeks gestation.

Fasting glucose and A1C are low-cost tests. A1C is convenient, but inaccuracies exist in increased red blood cell turnover and hemoglobinopathies (usually lower) and higher values with anemia (224). A1C is unreliable for GDM or pre-existing diabetes screening at ≥15 weeks gestation. See Recommendation 2.3.

GDM indicates underlying β-cell dysfunction (225), increasing later diabetes risk, usually type 2, in the mother (226,227). Effective prevention interventions are available (228,229. GDM-diagnosed individuals should have lifelong prediabetes screening for interventions to reduce diabetes risk and type 2 diabetes screening for early treatment (230).

GDM Diagnosis Strategies

GDM poses risks to mother, fetus, and neonate. The HAPO study (231) showed continuously increasing adverse outcome risk with maternal glycemia at 24–28 weeks gestation, even within previously normal ranges. For most complications, there was no risk threshold, leading to GDM diagnostic criteria reconsideration.

GDM diagnosis (Table 2.7) can be achieved using:

- “One-step” 75-g OGTT (IADPSG criteria)

- “Two-step” approach: 50-g (nonfasting) screen followed by 100-g OGTT for screen positives (Carpenter-Coustan criteria).

Table 2.7. GDM Screening and Diagnosis Strategies

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; GLT, glucose load test; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

* American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists notes that one elevated value can be used for diagnosis (247).

Different diagnostic criteria identify different degrees of maternal hyperglycemia and risk, leading to debate on optimal GDM diagnosis strategies.

One-Step Strategy (IADPSG Criteria)

IADPSG defined GDM diagnostic cut points based on average fasting, 1-h, and 2-h PG values during 75-g OGTT in HAPO study participants at 24–28 weeks gestation, at which adverse outcome odds reached 1.75 times the odds at mean PG levels. This one-step strategy significantly increased GDM incidence (from 5–6% to 15–20%), primarily because only one abnormal value became sufficient for diagnosis (233). Regional studies have shown roughly one- to threefold prevalence increases with IADPSG criteria adoption (234. Increased GDM incidence could impact costs and medical infrastructure and potentially “medicalize” previously normal pregnancies. An 11-year follow-up of HAPO participants showed that those diagnosed with GDM by the one-step approach had a 3.4-fold higher prediabetes and type 2 diabetes risk and children with higher obesity risk, suggesting benefits from increased screening and follow-up (235,236). The ADA recommends IADPSG criteria to optimize gestational outcomes as they are based on pregnancy outcomes.

Expected offspring benefits are inferred from intervention trials on lower hyperglycemia levels than older GDM criteria identified. These trials showed modest benefits, including reduced large-for-gestational-age births and preeclampsia (237,238). 80–90% of participants treated for mild GDM in these trials could be managed with lifestyle therapy. OGTT glucose cutoffs in these trials overlapped IADPSG thresholds, and one trial’s 2-h PG threshold was lower than IADPSG’s cutoff (238).

No randomized controlled trials of treating versus not treating GDM diagnosed by IADPSG but not Carpenter-Coustan criteria have been published. However, a recent trial comparing one-step (IADPSG) versus two-step GDM testing found twice as many GDM cases with one-step, but no difference in pregnancy complications despite treating more individuals in the one-step group (239). Concerns exist about sample size and suboptimal protocol engagement (240). High prediabetes prevalence in childbearing age may support more inclusive IADPSG criteria. NHANES data show 21.5% prediabetes prevalence in 20–44 year olds, comparable to or higher than one-step GDM prevalence (241).

The one-step method identifies long-term maternal prediabetes and diabetes risks and offspring abnormal glucose metabolism and adiposity. Post hoc GDM in one-step diagnosed individuals in HAPO was associated with higher offspring IGT prevalence, glucose levels, and reduced insulin sensitivity at 10–14 years compared to offspring of mothers without GDM (236,242). HAPO FUS data show neonatal adiposity and fetal hyperinsulinemia are mediators of childhood body fat (243).

Data on how maternal hyperglycemia treatment in pregnancy affects offspring obesity, diabetes, and metabolic disorder risk are lacking. More clinical studies are needed to determine optimal monitoring and treatment intensity for one-step GDM diagnosis (244,245).

Two-Step Strategy (NIH and ACOG Recommendations)

In 2013, NIH convened a consensus conference recommending a two-step GDM screening approach: 1-h 50-g GLT followed by 3-h 100-g OGTT for screen positives (246). ACOG recommends 130, 135, or 140 mg/dL thresholds for 1-h 50-g GLT (247). A 2021 USPSTF review continues to conclude one-step versus two-step screening increases GDM likelihood (11.5% vs. 4.9%) without improved health outcomes. Oral glucose challenge tests using 140 or 135 mg/dL thresholds had sensitivities of 82% and 93% and specificities of 82% and 79% against Carpenter-Coustan criteria. Fasting plasma glucose cutoffs of 85 mg/dL or 90 mg/dL had sensitivities of 88% and 81% and specificities of 73% and 82% against Carpenter-Coustan criteria (248). A1C at 24–28 weeks is not as effective as GLT for GDM screening (249).

Key NIH panel factors were lack of clinical trial data on one-step strategy benefits and potential negative consequences of increased GDM diagnoses, including pregnancy medicalization and increased costs. 50-g GLT is easier as it doesn’t require fasting. Treating higher-threshold maternal hyperglycemia (two-step approach) reduces neonatal macrosomia, large-for-gestational-age births (250), and shoulder dystocia without increasing small-for-gestational-age births. ACOG supports the two-step approach but notes one elevated value may be used for GDM diagnosis (247. ACOG recommends either Carpenter-Coustan or National Diabetes Data Group diagnostic thresholds for 3-h 100-g OGTT (251,252). A secondary analysis showed treatment benefit was similar for people meeting only lower Carpenter-Coustan thresholds (251) and those meeting only higher National Diabetes Data Group thresholds (252). If using the two-step approach, Carpenter-Coustan lower thresholds are advantageous (Table 2.7).

Future GDM Diagnostic Considerations

Conflicting expert recommendations highlight data supporting each strategy. Economic reviews suggest one-step method identifies more GDM cases and is more likely cost-effective (254). Strategy choice should be based on values placed on factors yet to be measured (e.g., willingness to change practice based on correlation studies, infrastructure, cost).

IADPSG criteria (“one-step strategy”) are internationally preferred. Data comparing population outcomes with one-step versus two-step approaches are inconsistent (239,255–257). Pregnancies complicated by GDM per IADPSG but not recognized have outcomes comparable to pregnancies with GDM diagnosed by stricter two-step criteria (258,259). There is strong consensus for a uniform GDM diagnostic approach. Longer-term outcome studies are underway.

Footnotes

Disclosure information for each author is available at https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-SDIS.

Suggested citation: ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al., American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2023;46(Suppl. 1):S19–S40