This article outlines the rigorous methodology employed in our meta-analysis investigating the clinical diagnosis of depression within primary care settings, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Our aim was to comprehensively assess the detection rates of depression by primary care clinicians compared to gold standard diagnostic evaluations. This systematic approach, registered with PROSPERO (CRD42016039704), ensures the robustness and reliability of our findings, contributing valuable insights to the field of mental health in primary care.

Comprehensive Search Strategy for Identifying Relevant Studies

To capture all relevant research, we conducted an extensive search across several key databases from their inception up to the third week of December 2020. These databases included MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, and PubMed, ensuring a broad coverage of medical and psychological literature. We further expanded our search to encompass regional databases such as the Latin America and Caribbean Center on Health Science Literature (LILAC) and African Journal of Online (AJOL), acknowledging the importance of including research specific to LMICs. Manual searches were also undertaken to identify any studies not indexed in these databases.

Our search strategy utilized a combination of terms to effectively identify studies focusing on the clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care. We employed search terms related to “Depression” such as “Depression”, “depressive disorder”, and “Common mental disorder”. To target detection and diagnosis, we included terms like “Detection”, “Detection rate”, “Prevalence”, “Screening”, “Case finding”, “Diagnosis”, “Undiagnosed”, and “under-detection”. Finally, to specify the primary care setting, we used “Primary health care”, “primary care”, and “Health centers”. These terms, along with the World Bank definition and list of countries to identify LMICs, were combined using the Boolean operator “AND” to refine our search and ensure relevance (refer to Supplementary file 1 for detailed search strings).

Defining Outcomes of Interest: Detection and Prevalence

The primary outcome of our meta-analysis was detection, specifically defined as the proportion of patients accurately diagnosed with depression by primary care clinicians when compared against a “gold” standard diagnosis. This gold standard was established using locally validated instruments or a confirmatory clinical diagnosis rendered by a mental health expert. This rigorous comparison is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of depression diagnosis in primary care settings.

As a secondary outcome, we examined the prevalence of depression within the studies that reported detection rates. Understanding the prevalence alongside detection provides a more complete picture of the burden of undiagnosed depression. Furthermore, we explored factors potentially associated with detection rates to identify areas for improvement in clinical practice.

Inclusion Criteria for Study Eligibility

To ensure the quality and focus of our meta-analysis on clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care, we established clear eligibility criteria for study inclusion:

-

Diagnosis of Depression: Studies were required to include adults and adolescents aged 15 years and older diagnosed with depression. This encompassed a broad spectrum of depressive disorders, including major depressive disorder, bipolar depression, masked depression, secondary depression, minor depression, and sub-threshold depression. The diagnosis had to be made by primary care clinicians, regardless of whether interventions were offered.

-

Study Setting in LMICs: Studies were required to be conducted in LMICs, as defined by the World Bank classification at the time of publication (https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519). This focus on LMICs is critical due to the unique challenges and contexts of mental health care in these regions.

-

Primary Health Care Setting: Participants had to be recruited from primary health care settings, recognized as the foundational element of ongoing healthcare processes [19]. This criterion ensures the meta-analysis directly addresses depression diagnosis within the intended primary care context.

-

Study Type: We included prospective studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, and clinical trials, provided their aim was to evaluate the impact on detection rates. This broad inclusion of study designs allowed for a comprehensive synthesis of evidence.

-

Language and Publication Year: No language restrictions were imposed to minimize bias, and we included primary studies published from the inception of the respective databases up to December 2020.

Quality Assessment of Included Studies

To critically evaluate the methodological rigor of the included studies, we utilized the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool [20]. This tool assesses studies across eight key domains: selection bias, study design, control of confounders, blinding of outcome assessors, data collection methods, withdrawals and dropouts, analysis, and intervention integrity. Due to the limited number of interventional studies focused on detection rates, the intervention integrity criterion was excluded from the overall rating. Consequently, five of the eight quality items were used for the global quality rating.

Studies were assigned a global quality rating of “weak,” “moderate,” or “strong” based on the EPHPP assessment. A “strong” rating was given if no weak ratings were present across the assessed domains, “moderate” if only one weak rating was assigned, and “weak” if two or more “weak” ratings were identified. This quality assessment process is essential for understanding the limitations and strengths of the evidence base for clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care.

Furthermore, we employed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist [21] as a secondary tool to evaluate the quality of reporting. Two authors independently rated each of the 22 STROBE items as “fully reported,” “partially reported,” or “not reported,” adhering to the STROBE guidelines. This dual assessment approach ensured a thorough evaluation of both methodological quality and reporting transparency.

Data Extraction Process

The study selection and data extraction processes were conducted rigorously to minimize bias. Initially, two authors independently screened studies based on titles and abstracts. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third author, ensuring consensus on study inclusion. Reasons for excluding articles were meticulously documented.

Data extraction was also performed independently by the same two authors using a pre-piloted data extraction form. This form captured key study characteristics including study country, study design, sample size, the number of patients detected with depression by clinicians, the number detected by the “gold” standard tool, and the reported outcomes (detection, prevalence, and associated factors). This systematic data extraction process ensured the accurate and comprehensive synthesis of findings related to clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care.

Statistical Analysis: Meta-Analysis and Heterogeneity

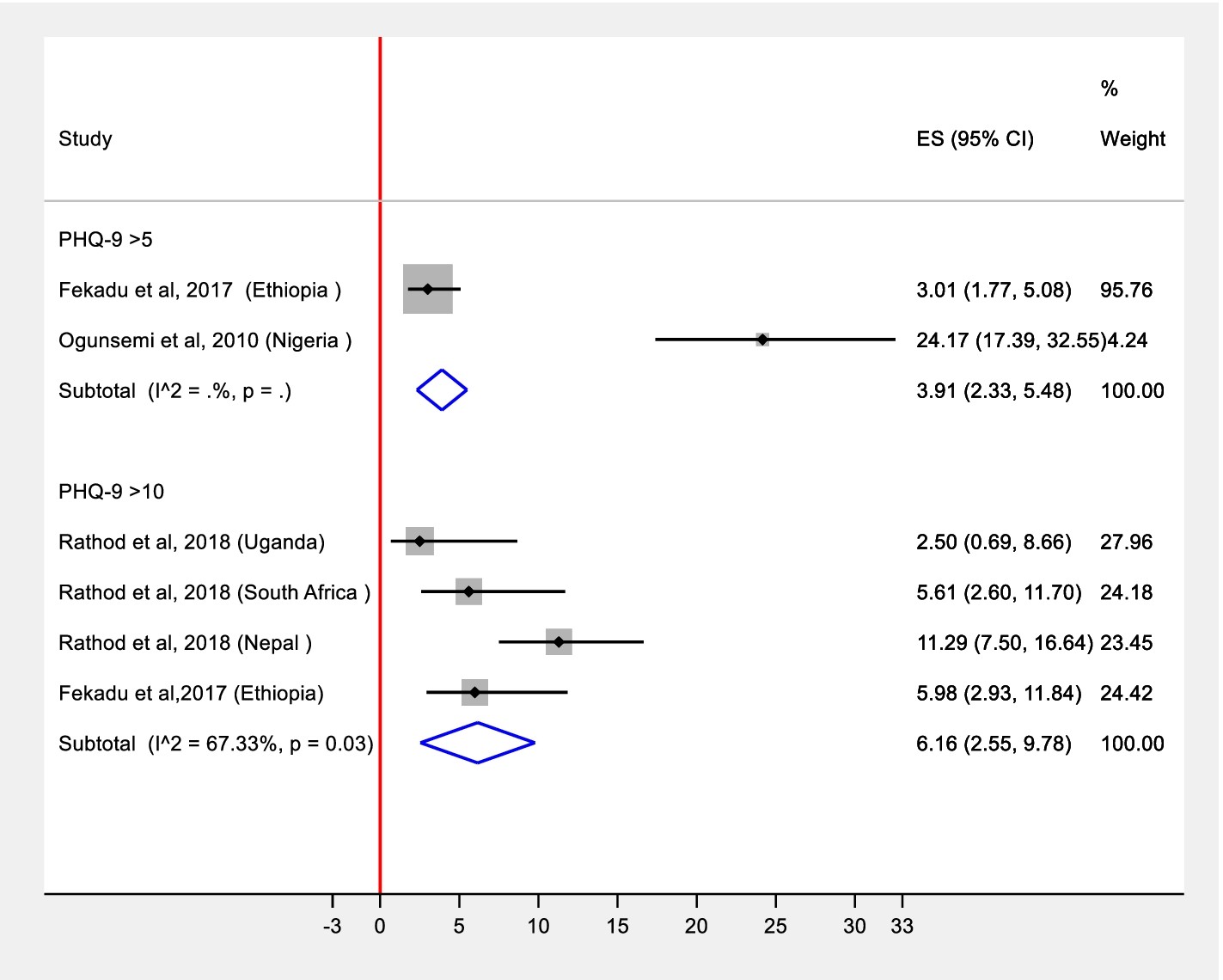

Our statistical analysis involved a meta-analysis stratified by diagnostic approaches. We grouped studies based on the diagnostic instruments used, including the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) with two different diagnostic thresholds, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). This stratification allowed for a more nuanced understanding of depression detection across various clinical tools.

Pooled prevalence estimates were calculated for PHQ-9 with cut-off 5 (from two studies), PHQ-9 with cut-off 10 (from six studies), and SCID-based diagnosis (from two studies). Studies utilizing BDI and EPDS in specific populations (diabetes and antenatal clinic attendees, respectively) were excluded from the main meta-analysis due to the potential for different depression prevalence and detection rates in these specialized groups. These were reported as individual studies to acknowledge their findings.

Alt: Forest plot displaying meta-analysis results for depression detection rates in primary care settings, illustrating pooled estimates and confidence intervals.

We generated two primary effect size (ES) estimates: (a) detection of depression, defined as the proportion of patients correctly diagnosed by primary health care workers compared to a “gold” standard; and (b) prevalence of depression, representing the proportion of participants scoring above the cut-off in the “gold” standard diagnosis. Given the expected heterogeneity across diverse settings, we employed a random effects meta-analysis model [24] to account for this variability. The assumptions of the random effects model were tested using normal probability plots of residuals, which confirmed the adequacy of the model for both prevalence and detection estimates [25]. The metaprop command in STATA/SE version 16 was used to conduct the meta-analysis, further ensuring the statistical rigor of our findings related to the clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care.

Alt: Forest plot visualizing pooled prevalence of depression in primary care from meta-analysis, showing prevalence estimates and confidence intervals across studies.