Introduction

Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) is a common concern in infants, estimated to affect 2–3% of this population. However, diagnosing CMA presents challenges due to its varied and often nonspecific symptoms. Parents’ perceptions of CMA prevalence often exceed the actual figures, leading to potential overdiagnosis. Since accurate diagnosis is crucial to avoid unnecessary dietary restrictions and ensure appropriate management, this article focuses on the essential methods for reliable Cma Diagnosis.

Defining Cow’s Milk Allergy

Adverse reactions to cow’s milk protein (CMP) can manifest from infancy, even in exclusively breastfed babies. It’s important to distinguish between different types of reactions. Food hypersensitivity is the overarching term, encompassing both non-allergic food hypersensitivity (food intolerance) and allergic food hypersensitivity (food allergy). Food allergy, specifically, involves an immune system response. The majority of CMA cases are immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated, often linked to atopic conditions like eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis. A smaller subset of children experiences cell-mediated allergy, primarily affecting the gastrointestinal system. Understanding these distinctions is the first step in accurate CMA diagnosis.

The Role of History and Physical Examination in CMA Diagnosis

While signs and symptoms alone (as detailed in Table 1) are not definitive for CMA diagnosis, a thorough medical history can offer valuable clues and guide diagnostic direction. Symptom onset following formula introduction instead of breastfeeding can be suggestive. Immediate reactions like urticaria or rash after CMP ingestion are also indicative of CMA. Generally, delayed symptoms (occurring more than 2 hours post-CMP consumption) are less likely to be CMA-related. Inconsistent symptoms that don’t occur after every feeding also point towards alternative causes.

Table 1. Signs and Symptoms Suggestive of Cow’s Milk Allergy (CMA)

| Gastrointestinal | Skin | Respiratory | General |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vomiting | Rash | Rhinitis | Food refusal |

| Regurgitation | Atopic eczema | Conjunctivitis | Growth retardation |

| Abdominal pain | Urticaria | Hoarseness, dysphagia | Iron-deficient anaemia |

| Colic | Swollen lips | Wheezing, asthma | Irritability, disturbed sleep |

| Diarrhoea | Angio-oedema | Apnoea, apparent life-threatening events | |

| Constipation | Pruritus | Anaphylaxis | |

| Haemochezia |

Signs and symptoms in italics are suggestive of severe allergy.

The presence of other atopic conditions like eczema, wheezing, and asthma increases the likelihood of CMA but doesn’t confirm the CMA diagnosis. The relationship between CMA and eczema is particularly complex. While they can coexist, and CMP challenges might worsen moderate to severe eczema in some cases, there’s no proven link with mild eczema. Crucially, eczema should be managed with topical treatments before considering CMA diagnosis. Physical examinations are often unremarkable or reveal nonspecific findings. Monitoring growth is important.

Laboratory Tests: Sensitization vs. Allergy in CMA Diagnosis

Laboratory investigations play a limited and often misinterpreted role in CMA diagnosis. Available tests only detect sensitization to CMP, which doesn’t automatically equate to a clinically relevant allergy. More than half of sensitized children do not actually have a food allergy. Positive skin prick tests and allergen-specific IgE tests are frequently misconstrued as confirmation of CMA, which can lead to unnecessary dietary restrictions.

While a strong correlation exists between allergen-specific IgE levels and the probability of CMA, unequivocally high levels are uncommon and can even occur in non-allergic children. Therefore, in general practice, laboratory tests are rarely conclusive for CMA diagnosis. The gold standard for confirming CMA diagnosis remains elimination and challenge procedures.

Cow’s Milk Challenge: Open vs. Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled

Following CMP elimination from the child’s or breastfeeding mother’s diet, CMA-related signs and symptoms should subside within days, although eczema improvement might take up to four weeks. A cow’s milk challenge involves reintroducing CMP to observe for symptom recurrence.

Challenges can be performed openly or double-blindly. Open challenges involve both the testers and parents knowing that CMP is being administered. Double-blind placebo-controlled food challenges (DBPCFC) are designed to eliminate bias by concealing whether CMP or a placebo is being given from both parents and staff. DBPCFC utilizes placebo and verum (active CMP) in random order, with CMP disguised to ensure identical appearance and taste. DBPCFC are more reliable for CMA diagnosis but are more complex, time-consuming, and resource-intensive compared to open challenges.

Open Challenge: Ruling Out CMA

Open challenges serve as an initial step in CMA diagnosis, primarily useful for excluding CMA. These challenges should adhere to established protocols tailored to specific settings. A Dutch protocol, for instance, involves an initial small dose of standard formula followed by increasing amounts over several days, under observation. However, it’s now recognized that open challenges can lead to falsely positive CMA diagnosis due to subjective symptom interpretation and symptom fluctuation. Studies show that a significant proportion of open-challenge CMA diagnoses are refuted by DBPCFC.

A generally accepted open challenge procedure involves gradually increasing the child’s usual formula intake over a few hours. However, experts recommend limiting open challenges to ruling out CMA, as they are prone to overestimating CMA prevalence.

Table 2. CMP Administration Schedules During Challenge: Open Challenge vs. DBPCFC

| Step | Open Challenge; Child’s Own Formula | DBPCFC; Hypoallergenic Formula with Protifar® |

|---|---|---|

| T (min) | Dose (ml) | CMP (mg)a |

| 1 | 0 | Drop on lips |

| 2 | 15 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 45 | 1.0 |

| 4 | 75 | 3.0 |

| 5 | 105 | 10 |

| 6 | 135 | 30 |

| 7 | 165 | 50 |

| 8 | 195 | 100 |

| Total | 195 | 2,925 |

aBased on a mean protein content of 1.5 g/100 ml. Protein content varies between infant formulas (1.3-1.6 g/100 ml) and follow-on formulas (1.7-1.9 g/100 ml).

DBPCFC: The Gold Standard for CMA Diagnosis

DBPCFC is recognized as the gold standard for accurate CMA diagnosis. Many pediatric allergy centers and hospitals utilize DBPCFC. With proper training, patient selection, and emergency preparedness, DBPCFC can also be implemented in well-baby clinics and general practices. The necessity of DBPCFC is highlighted by the fact that placebo reactions occur in a notable percentage of tests, emphasizing the impact of subjective interpretation in open challenges. While no universally standardized DBPCFC protocol exists, a widely used protocol is outlined below.

Preparation: A CMP-free diet for at least two weeks is required before DBPCFC. The patient’s condition should be stable, particularly concerning skin symptoms. Topical corticosteroids can continue, but antihistamines should be discontinued at least one week prior. A thorough history of prior adverse reactions is essential.

Safety: DBPCFC should be conducted in a day-care setting or during hospital admission. Depending on the severity of previous symptoms, monitoring equipment and intravenous access might be necessary. Emergency medications like clemastine and epinephrine must be readily available, and personnel must be trained in managing potential acute reactions.

Test Material: The child receives their usual hypoallergenic formula or expressed breast milk. Coded bottles are prepared, containing either verum (with CMP) or placebo (without CMP). Verum is created by adding 5g of Protifar® powder (containing 4.4g CMP) per 250ml of formula, ensuring both placebo and verum appear identical.

Procedure: Placebo and verum are administered on separate days, ideally one week apart. The test formula is given in increasing doses at set intervals (Table 2). Adverse reactions are meticulously recorded. After a negative test, a 2-hour observation period follows; a 4-hour period follows a positive test. Parents are instructed to report any late reactions. A follow-up period of at least 48 hours after the second test is observed before unblinding the results.

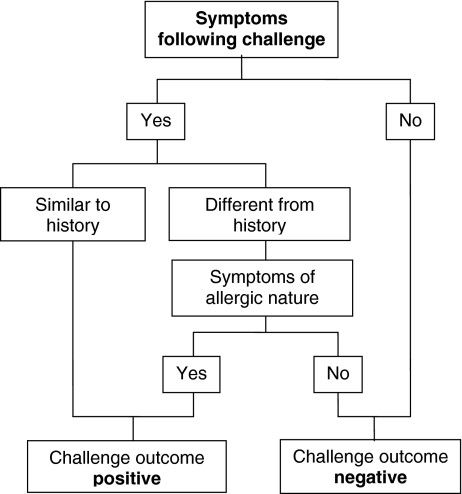

Evaluation: The test is stopped if objective adverse reactions, subjective reactions lasting 30 minutes or longer, or repeated brief subjective reactions occur. Allergic and non-allergic reactions are evaluated separately, considering the child’s medical history (Figure 1). Table 3 provides guidance for interpreting DBPCFC outcomes. A DBPCFC is considered negative if verum doesn’t trigger worse reactions than placebo. However, even DBPCFC results can be ambiguous in some cases.

Fig. 1. Algorithm for DBPCFC Evaluation in CMA Diagnosis

Algorithm for DBPCFC Evaluation in CMA Diagnosis

Algorithm for DBPCFC Evaluation in CMA Diagnosis

Algorithm outlining the evaluation process for Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Food Challenge (DBPCFC) tests in diagnosing Cow’s Milk Allergy (CMA). The diagnosis is determined by analyzing the combined results of both placebo and verum tests, as detailed in Table 3. Adapted from reference [26].

Table 3. Interpretation of DBPCFC Results for CMA Diagnosis

| Verum Challenge Result | Placebo Challenge Result | DBPCFC Test Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Positive |

| Strongly Positive | Positive | Positive |

| Positive | Positive | Negative |

| Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Positive | Strongly Positive | Negative |

Table outlining the interpretation of Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Food Challenge (DBPCFC) results to determine the diagnosis of Cow’s Milk Allergy (CMA). Adapted from reference [26].

Risk Assessment During CMA Diagnosis Challenges

Predicting reaction severity during food challenges is challenging, but certain risk factors exist. Severe reactions are more likely in children with a history of severe reactions, reactions to minimal CMP doses, older age, asthma, and prolonged cow’s milk avoidance.

However, severe reactions during CMP challenges are infrequent. Extensive open challenge programs in well-baby clinics have reported no severe adverse events. Similarly, the described DBPCFC protocol has been safely used in hundreds of challenges without severe reactions. Therefore, CMP challenges, particularly DBPCFC for CMA diagnosis, can be safely performed in general practices when basic safety measures are followed. High-risk challenges should be conducted in a hospital setting.

Cow’s Milk Reintroduction After CMA Diagnosis Refutation

When CMA diagnosis is ruled out through DBPCFC, standard formula and dairy products can be safely reintroduced. In some cases, parental anxiety due to the child’s prior symptoms may require dietician support to facilitate a smooth transition back to a normal diet. If symptoms reappear after reintroduction, they may be due to the underlying condition’s natural course (e.g., eczema) or parental apprehension, and often resolve with continued introduction.

Therapy for Confirmed CMA Diagnosis

Currently, CMP elimination from the diet is the only proven therapy for confirmed CMA diagnosis.

Breastfed Infants: Breastfeeding mothers need to eliminate all dairy products from their diet. The necessity of eliminating other potential allergens like soy, egg, and beef is debated. A practical approach is to initially eliminate CMP and consider further restrictions only if symptoms persist.

Formula-fed Infants: Hypoallergenic formulas based on extensively hydrolyzed CMP are the standard replacement. Soy formulas are generally not recommended for infants under six months with CMA due to potential cross-reactivity. Suitable formulas are those proven to be tolerated by at least 90% of CMA patients. Protein sources can be extensively hydrolyzed whey protein (eHW) or casein (eHC). While some children may tolerate one type better than the other, no clear clinical efficacy difference exists between eHW and eHC formulas. Amino-acid-based formulas are reserved for children who do not tolerate extensively hydrolyzed formulas, particularly those with non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal CMA or severe atopic eczema.

Solids Introduction: Delaying solid food introduction or following strict schedules is unnecessary. Most children tolerate non-dairy solids introduced after 4 months. In highly allergic children, a gradual introduction of one or two new foods every 3 days is advisable. Dietary guidance is often needed to address parental anxiety regarding solid food introduction.

Counseling: A CMA diagnosis significantly impacts families. Comprehensive parent and caretaker education is essential, covering avoidance strategies (food label reading, risk situation awareness), early symptom recognition, and acute reaction management. Antihistamines are prescribed for mild dermal reactions, but epinephrine auto-injectors and individualized treatment plans are necessary for children with a history of anaphylaxis.

Tolerance Induction and CMA Prognosis

Oral or sublingual immunotherapy for CMA in older children is an area of growing interest. Immunotherapy may raise the tolerance threshold to CMP and potentially induce permanent tolerance. However, further research is needed before it becomes a routine therapeutic option.

CMA is often a transient condition. While earlier estimates suggested 85% of children develop tolerance by age 3, more recent studies indicate that IgE-mediated CMA may persist longer in some children. Regular re-evaluation with challenges is recommended to minimize unnecessary dietary restrictions. Challenges can be scheduled at 12, 18, and 24 months, and annually thereafter, especially if a proper CMA diagnosis via DBPCFC hasn’t been previously established.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do have do conflict of interest and no financial relationships that might have influenced the present work.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Contributor Information

C. M. Frank Kneepkens, Phone: +31-20-4444444, FAX: +31-20-4442918, Email: [email protected].

Yolanda Meijer, Email: [email protected].

References

[1] Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Vlieg AV, van den Elsen M, et al. Double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge in children with cow’s milk allergy: diagnostic value of symptom scores and cytokine responses. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35(12):1591–8.

[2] Høst A. Cow’s milk protein allergy and intolerance in infancy. Some clinical, epidemiological and immunological aspects. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1994;5(5 Suppl):1–36.

[3] Hill DJ, Hosking CS. Gastrointestinal allergy in infancy: role of cow milk allergy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 1997;15(1):1–23.

[4] Saarinen UM, Juntunen-Backman K, Järvenpää AL, Klemetti E, Siimes MA. Breastfeeding and cow’s milk allergy: a 13 year prospective follow-up study. Arch Dis Child. 1995;72(3):F3-F7.

[5] Isolauri E, Sutas Y, Mäkinen-Kiljunen S, Oja SS, Isosomppi R, Turjanmaa K. Efficacy and safety of hydrolyzed cow milk versus formula based on cow milk in infants with cow milk allergy. J Pediatr. 1995;127(4):550–7.

[6] Bindslev-Jensen C, Bengtsson U, Stahl Skov P, et al. Accidental reactions to cow’s milk and hen’s egg in children thought to be tolerant: a prospective study. Allergy. 2002;57(10):978–86.

[7] Johansson SG, Hourihane JO, Bousquet J, et al. EAACI nomenclature task force. Allergy. 2001;56(6):481–8.

[8] Sampson HA. Food allergy. Part 1: Immunopathogenesis and clinical reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(5 Pt 1):717–28.

[9] Koletzko S, Niggemann B, Arato A, et al. Diagnostic approach and management of cow’s milk allergy in infants and children: European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55(2):221–9.

[10] Werfel S, Ballmer-Weber BK, Eigenmann PA, et al. Eczema Task Force of the EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group. Allergy. 2007;62(Suppl 85):1–19.

[11] Høst A, Halken S, Jacobsen HP, et al. Clinical course of cow’s milk allergy/intolerance and atopic dermatitis in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13(Suppl 15):23–8.

[12] Muraro A, Werfel S, Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, et al. EAACI food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines. Allergy. 2014;69(8):1008–25.

[13] Bath-Hextall FJ, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary exclusions for established atopic eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD005203.

[14] Sporik R, Hill DJ, Hosking CS. Specificity of allergen skin testing in early childhood. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998;28(9):1028–37.

[15] Foucard T, Malmheden Yman I. IgE antibodies to food proteins. A comparison of results obtained by different in vitro tests. Allergy. 1999;54(5):474–84.

[16] Molkhou AS, Caubet JC, Eigenmann PA, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Santos AF, Dubois AE, et al. Allergy diagnosis via component resolved allergology: added value for the diagnosis of peanut, cow’s milk and egg allergy. Allergy. 2013;68(10):1235–45.

[17] Sampson HA, Ho DG. Relationship between food-specific IgE concentrations and the probability of positive food challenges in children with atopic dermatitis and suspected food hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100(4):444–51.

[18] Perry TT, Matsui EC, Kay Conover-Walker M, Wood RA. Risk factors for food allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106(1 Pt 1):170–3.

[19] Rognum TO, Lund E, Nafstad P, Gaarder PI, Magnus P. Prevalence of self-reported food hypersensitivity in pre-school children in Oslo. Eur J Epidemiol. 2002;18(4):351–6.

[20] de Meer K,তের Gobel JW, Benninga MA, Buller HA. Cow’s milk allergy in infancy. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment. Dutch National Consensus Group on Cow’s Milk Allergy. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1996;140(2):78–81.

[21] Vandenplas Y, de Greef E, Hauser B, et al. An open tolerance test with extensively hydrolysed formula can predict the outcome of a double-blind placebo-controlled challenge in infants with cow’s milk allergy. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94(2):199–203.

[22] Martorell-Aragonés A, Echeverría-Zudaire L, Alonso-Lebrero E, et al. Open oral food challenge with cow’s milk proteins after negative skin prick test with extensively hydrolyzed cow’s milk proteins in infants with cow’s milk allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;25(1):59–64.

[23] Bulder MM, de Jong NW, van den Burgt RJ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of cow’s milk allergy in general practice. Huisarts Wet. 2007;50(1):4–10.

[24]তের Jong NW, ter Riet G, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, et al. The double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge in cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(4):870–5.

[25] Meijer Y, ter Riet G, Knol EF, et al. Placebo-controlled food challenges in children: single centre experience over a 15-year period. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39(8):1227–35.

[26]তের Riet G, ter Stege J, Knol EF, Kuperus-Ubels I, Meijer Y, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ. How to perform a double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(3):211–7.

[27] Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Vlieg AV, Olijve LL, et al. Placebo-reactions during double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges in children with cow’s milk allergy. Allergy. 2005;60(1):82–7.

[28]তের Stege J, ter Riet G, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, et al. Diagnostic value of the double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge in cow’s milk allergy: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(2):309–17, 317.e1-4.

[29] Bock SA, Sampson HA, Atkins D, et al. Appraisal of double-blind placebo-controlled food challenges. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(4):443–7.

[30] Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Bloom B, Sicherer SH, Shreffler WG, Noone S, Mayer L, Sampson HA. Tolerance to baked milk in children with cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(3):647–8.

[31] Skripak JM, Matsui EC, Mudd K, Baker RD, Sampson HA, Wood RA. The natural history of IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5):1172–7.

[32] Lothe L, Lindberg T, Jakobsson I. Cow’s milk whey protein elicits symptoms of cow’s milk allergy in the majority of cow’s milk allergic infants. Clin Exp Allergy. 1990;20(4):417–22.

[33] Zeiger RS, Sampson HA, Bock SA, et al. Soy allergy in infants and children with cow milk allergy. J Pediatr. 1999;134(5):614–22.

[34] Vandenplas Y, Koletzko S, Isolauri E, Hill D, de Greef E, Heine R, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk protein allergy. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(10):902–8.

[35] Isolauri E, Rautava P, Oja SS, Arvilommi H, Isolauri J, Salminen S. Probiotics in the management of atopic eczema. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30(11):1604–10.

[36] Simons FE, Frew AJ, Simons KJ, et al. Risk assessment in life-threatening anaphylaxis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37(6):829–37.

[37] Patel N, Leung TF, Li PH, et al. Oral immunotherapy for cow’s milk allergy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(1):58–70.

[38] Pajno GB, Caminiti L, Vita D, et al. Oral immunotherapy for cow’s milk allergy: 5-year follow-up. Allergy. 2010;65(5):647–51.

[39] Blumchen K, Verhoeckx KC, Vieths S, et al. Cow’s milk allergy: oral tolerance induction and prospects for specific immunotherapy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11(3):251–7.

[40] Host A, Halken S. Cow’s milk allergy: current concepts and management. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31(Suppl):S2-S17.

[41]তের Wolde SA, тег Riet G, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, et al. Natural course of cow’s milk allergy in children up to 8 years of age. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47(6):805–13.

[42] Wood RA, Sicherer SH, Vickery EM, et al. The natural history of milk allergy in an observational cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(1):80–6.