1. Introduction

In the realm of primary health care and public health initiatives, the Community Diagnosis Definition stands as a cornerstone for effective intervention and health improvement strategies. A community diagnosis is fundamentally a systematic process designed to provide a comprehensive understanding of a community’s health status. This encompasses not only a detailed description of the community itself but also a thorough evaluation of its overall health, identifying key factors that influence this health, and recognizing the specific needs as perceived by the community members themselves [[1](#B1-ijerph-18-09661)].

The consensus among healthcare professionals and researchers is that interventions aimed at improving community health must be precisely tailored to the unique needs identified within that community. This necessitates a collaborative approach, working hand-in-hand with the community to pinpoint these needs and determine the most effective strategies for addressing them. Such strategies must consider the multifaceted factors impacting the community and develop adaptable models and approaches to ensure optimal outcomes [[2](#B2-ijerph-18-09661), 3, 4]. When a community diagnosis is effectively executed, it serves as a catalyst for strengthening bonds among various community stakeholders – from residents and public health workers to institutions and beyond. This collaborative spirit fosters community leadership and empowerment, creating fertile ground for community-driven initiatives focused on action and positive change [[5](#B5-ijerph-18-09661)]. Crucially, any community-based process, especially a community diagnosis, must conclude with a rigorous evaluation and analysis to ascertain its effectiveness and impact [[6](#B6-ijerph-18-09661), 7].

The foundation of this approach to community diagnosis rests on a holistic conceptualization of health. Health is not merely the absence of disease but a fundamental human right, a dynamic and personal experience shaped by an individual’s life within a community. This community context includes shared economic, social, and cultural characteristics, and is significantly influenced by environmental factors and the established norms of communal living. Community health, therefore, is the collective expression of the well-being of all individuals and families within it. It reflects the intricate interplay of social, cultural, and environmental elements, the availability and accessibility of health services, and the overarching influence of social, political, and global determinants of health [[7](#B7-ijerph-18-09661)].

This study adopts a comprehensive paradigm for understanding community diagnosis definition. It emphasizes the importance of characterizing the community by thoroughly examining the social determinants of health present within it. This involves creating a detailed picture of daily life, embracing a holistic perspective that incorporates a positive and multidimensional understanding of health and well-being [[8](#B8-ijerph-18-09661), 9].

A community-centered approach to health, by its very nature, is participatory. The health diagnosis process is inherently a community endeavor, requiring the active involvement of three key groups: administrative bodies (local and higher levels), technical and professional resources (individuals directly engaged with the population and managing essential services like education, social welfare, sanitation, and economic support), and the citizens themselves. Citizen participation includes social organizations, both formal and informal groups, and other active members of public life who contribute to the entire process through their daily engagement [[6](#B6-ijerph-18-09661), 7, 10].

Meaningful inclusion of women in this participatory process is essential. Their involvement leads to improved health protection, promotion, and self-care, both for women and the wider community. It achieves this by establishing platforms for dialogue, consensus-building, and negotiation between community members and institutions. Furthermore, recognizing women’s crucial roles in preserving traditional and contemporary knowledge, as well as cultural perspectives on health systems, is vital [[11](#B11-ijerph-18-09661), 12]. While some studies acknowledge women’s roles in community diagnoses [[13](#B13-ijerph-18-09661), 14, 15], their participation is often limited to that of informants, with minimal involvement in actual decision-making processes. Studies genuinely incorporating broad community participation in health diagnoses remain relatively uncommon.

Looking at examples within Spain, there are some notable precedents. A study in Ronda, Malaga, aimed to understand citizen perceptions of factors influencing community well-being and quality of life, moving beyond individualistic health models [[16](#B16-ijerph-18-09661)]. Another initiative in Las Remudas and La Pardilla, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, focused on improving quality of life through a community diagnosis undertaken jointly by residents, workers, and service providers. This collaborative diagnosis formed the basis for programming actions to enhance the entire area [[17](#B17-ijerph-18-09661)]. A third example from Barcelona [[5](#B5-ijerph-18-09661)], utilized mixed methods to conduct a community diagnosis in marginalized neighborhoods, combining desk reviews with focus groups, nominal groups, and individual interviews to achieve a comprehensive assessment of needs and potential solutions. Examples from Latin America [[18](#B18-ijerph-18-09661), 19] and Europe, including the Healthy Cities project of the late 1980s and early 1990s [[20](#B20-ijerph-18-09661)], further illustrate the application of community diagnoses. However, many of these studies primarily focused on identifying intervention priorities arising from the diagnoses, often lacking follow-up or evidence of medium to long-term implementation [[21](#B21-ijerph-18-09661), 22]. Furthermore, the gender perspective was notably absent in these prior instances.

The primary objective of this research was to conduct a community diagnosis from the distinct perspective of women living within the community. This approach centered on their lived experiences, beliefs, values, and opinions [[13](#B13-ijerph-18-09661), 23], with the aim of identifying modifiable social determinants of health to improve overall community health and to propose relevant, community-driven changes.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological design employed in this study aligned with community-based participatory research methods [[2](#B2-ijerph-18-09661)] to conduct a community diagnosis definition in action. Qualitative data collection and analysis were grounded in ethnographic methods [[24](#B24-ijerph-18-09661), 25]. This framework enabled researchers to establish a rich understanding of the community’s context, history, language, and general characteristics. It also facilitated the gathering of individual insights within this broader context, allowing for a deeper, more nuanced description and interpretation of the community’s culture, values, beliefs, and behaviors [[23](#B23-ijerph-18-09661), 26].

The chosen community for this study was Mañaria, situated in the central-southeastern region of Vizcaya, northern Spain. At the time of the research, Mañaria had a population of 522 residents, living in an urban center, five distinct neighborhoods, and dispersed rural houses (caseríos), a typical settlement pattern for the region. Table 1 illustrates the structure of the female population in Mañaria between 2009 and 2011, alongside the sample group selected for this study in 2008.

Table 1. Structure of the female population in Mañaria and sample population.

| Structure of the Female Population in Mañaria, by Age Group | Sample Selected for Interview, by Age Group and Zone within the Community (2008) |

|---|---|

| Neighborhood | |

| Age (years) | 2009 |

| n (%) | n (%) |

| 10–24 | 31 (14%) |

| 25–54 | 102 (46%) |

| 55–69 | 41 (18%) |

| ≥70 | 37 (17%) |

| Total | 211 |

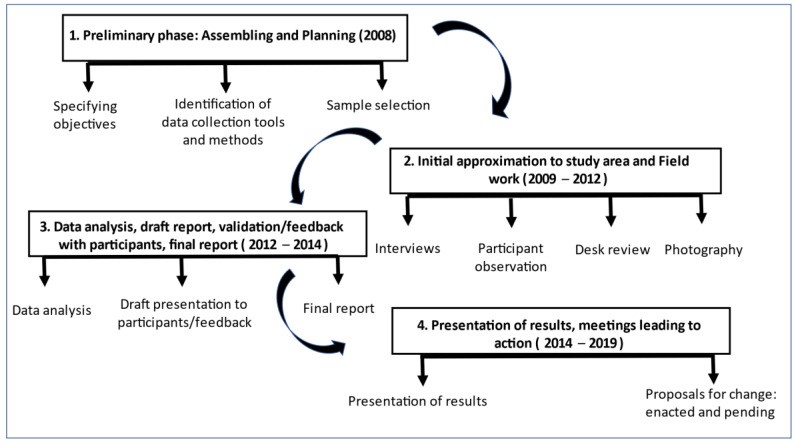

Fieldwork was conducted in two phases, in 2009 and 2014. Following data collection and analysis, and the summarization of key findings, researchers returned to the field. The purpose was to present the results to the community and collaboratively identify proposals for action. These proposals aimed to address challenges, mitigate negative aspects, and build upon positive findings. This phase was met with strong community engagement, encouraging the research team to present their action proposals to the wider community and local authorities. This led to the approval and implementation of several proposals by the study’s conclusion in 2019. Figure 1 provides a visual overview of the study phases from 2008 to 2019.

Figure 1. Phases of fieldwork (2008–2019).

The sample comprised 21 participants selected through purposive sampling. Researchers prioritized the availability of women to participate in qualitative interviews and sociodemographic questionnaires, aiming for maximum variability in socio-demographics, age, and geographical location [[27](#B27-ijerph-18-09661)]. In addition, five key informants were chosen. These were women with in-depth knowledge of the study’s topics of interest, who were approachable, and who could offer valuable insights [[28](#B28-ijerph-18-09661)]. Key informants included female professionals in medical and social services working within the community, leveraging their “network experience” [[29](#B29-ijerph-18-09661)]. Data collection ceased upon reaching saturation, defined as the point where subsequent interviews yielded no significant new relevant data [[24](#B24-ijerph-18-09661)].

Data collection methods included participatory observation, in-depth interviews, and semi-structured interviews, alongside a desk review of diverse sources and photographic documentation [[24](#B24-ijerph-18-09661), 30].

Initial interviews were exploratory, open-ended, and in-depth. In two instances, a second in-depth interview was conducted to further explore emerging themes and guide interpretation. In total, 28 in-depth interviews were carried out, averaging approximately one hour each. These interviews allowed the research team to understand implicit reasoning and identify values and beliefs surrounding health and its social determinants, as expressed in the narratives of the informants. Open-ended interviews helped identify key topics that were subsequently explored systematically through semi-structured interviews (Table 2). Semi-structured interviews were instrumental in collecting information and opinions based on the integral health paradigm, which provided the conceptual framework for the extracted categories (Table 2).

Table 2. Interview guide for in-depth and structured interviews.

| IN-DEPTH (General and Open-Ended Questions) | SEMI-STRUCTURED (Topics) |

|---|---|

| What do you think about the community’s health in Mañaria? | DEMOGRAPHIC STRUCTURE |

| What aspects may be involved to make this community more healthy or less healthy? | ECONOMIC STRUCTURE Business and public establishments Industry |

| What do you like about this community? | URBAN STRUCTURE Solid waste Cleanliness Urban design Urban furniture Housing Green areas Other urban aspects |

| What things do you miss? | SOCIAL SYSTEM Resources and community services Socializing process |

| What things do you think should improve? | HEALTH CARE SYSTEM Formal health care system Informal health care system |

Initial interview questions were broad, such as “What aspects do you like about this community?”, “What things do you miss?”, and “What aspects do you think could be improved?”. Subsequently, the focus shifted to community health-specific questions like “What is your opinion about community health in Mañaria?” and “What aspects may contribute to making this community healthier or less healthy?”.

Interviews were conducted in both Spanish and Euskera, the local autochthonous language. Using Euskera enhanced communication with native speakers, fostering rapport and empathy, crucial elements in qualitative interviewing [[24](#B24-ijerph-18-09661)].

Participatory observations took place across various times and locations. This allowed researchers to observe the variability in behaviors and discourses related to health, and to understand the context in which they occurred, thus facilitating meaning and interpretation. One author (MJA) resided in the community during fieldwork, further enhancing participatory observation opportunities.

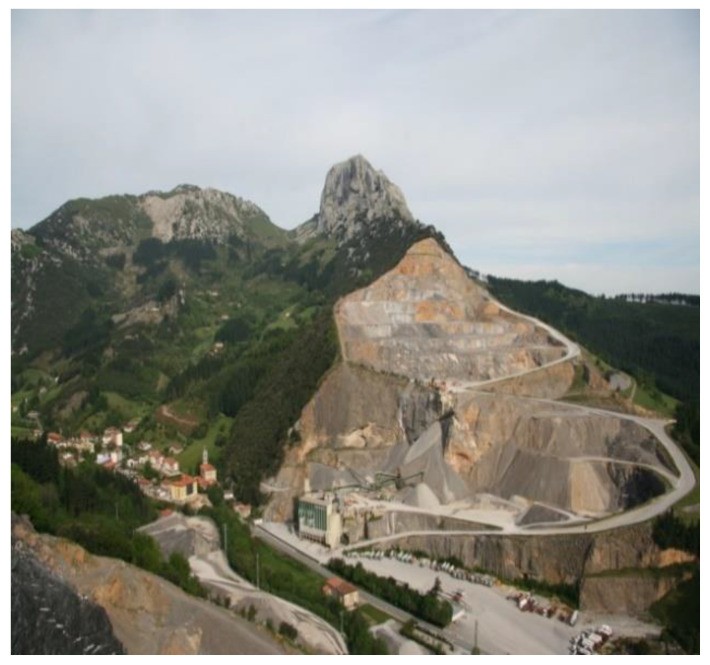

All observations were meticulously documented in a field diary [[24](#B24-ijerph-18-09661)], often supplemented with photographs of observed locations (Figure 2) [[30](#B30-ijerph-18-09661)]. These methods provided valuable contextual understanding, aiding data interpretation within the research team. For example, visualizing the impact of local quarries or the community work of auzolana (collaborative, unpaid community work) enhanced data analysis and triangulation.

Figure 2. Markomin-Goikoa quarry in Mount Mugarra.

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for text analysis. Manual coding preceded coding and categorization, followed by grouping and comparison of categories. Categories were developed inductively based on similarities and affinities, following the method proposed by Glaser and Straus [[31](#B31-ijerph-18-09661)], leading to the identification of meta-categories and thematic nuclei. This stage of analysis involved team discussion and consensus, strengthened by data triangulation and bias control. The analysis comprised three stages: coding and category identification, grouping into meta-categories, and thematic nuclei identification.

Draft results were presented to the 26 informants for validation and further discussion, aiming to refine interpretations and ensure participant ownership of their reality [[22](#B22-ijerph-18-09661), 32]. This process not only allowed for corrections but also yielded new information and nuanced understanding. Following consensual agreement on the final draft, results were presented at the Town Hall, leading to public debate and commitments from political and sanitation authorities. This process further empowered the participating women.

Ethical considerations, as outlined in the Helsinki Declaration, were integral to the research design. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Universidad Pública del País Vasco-Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki principles [[33](#B33-ijerph-18-09661)]. Oral consent was obtained from all participants before interviews, and audio recordings were made with informed consent, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality. Transcribed data was de-identified, using only letters and numbers for coding. Research rigor was ensured by following the COREQ guidelines [[34](#B34-ijerph-18-09661)] and criteria proposed by Calderón [[35](#B35-ijerph-18-09661)]: validity, adequacy, relevance, and reflexivity.

3. Results

3.1. The Sample

The sample included 26 women, with five key informants. The mean age was 47 years, with age group distribution as follows: 10–24 years (n = 2), 25–54 years (n = 12), 55–69 years (n = 5), and >70 years (n = 2). Twenty-three participants were permanent residents, and three worked full-time in the community. All geographical areas within the community were represented.

Four key informants were employed by the main government institutions: town hall, social services, and the sanitation system. The fifth was selected for her active involvement in a local civil association (Mañaria Bizirik).

3.2. Meta-Categories and Thematic Nuclei

Table 3 presents the meta-categories and thematic nuclei identified after coding.

Table 3. Meta-categories and thematic nuclei.

| Meta-Categories | Thematic Nuclei |

|---|---|

| Population | Housing |

| Work | |

| Environment | |

| Domestic and community economy | Non-remunerated work |

| Remunerated employment | |

| Community participatory work | |

| Public and private spaces | Public space: Quarries Main highway Architectonic barriers Mobility Esthetics Residues Public safety |

| Life habits and lifestyle | Food |

| Alcohol | |

| Tobacco | |

| Rest/sleep | |

| Leisure and free time | |

| Socializing process | Formal scenarios: Old school Childcare Cultural Center Central square Retiree House Townhall spaces |

| Health care resources | Care and informal caregivers Women, main providers Family Neighbors Social network Care |

Each thematic nucleus revealed problems, areas for improvement, health assets, and strengths, leading to proposals for change. Both the identified problems and assets, as well as the proposed actions, reflected a broad community diagnosis definition of health, closely linked to community actions spanning public health, economy, culture, education, and environment. Issues like unemployment, women’s dual burden of paid and domestic work, architectural barriers, limited resources for associations, lack of public transport, poor housing hygiene, and inadequate public space access were all identified as health problems due to their impact on overall well-being and quality of life. Recognizing wellness as integral to community health underscores that the public health sector is just one facet, often less influential than structural, social, and political sectors [[36](#B36-ijerph-18-09661)]. The main problems and health assets are detailed below within each meta-category.

3.3. Meta-Categories

3.3.1. Population

This category encompassed issues related to housing (high costs, scarcity), the necessity of commuting for work, environmental degradation from quarrying, and service shortages. Informants emphasized these factors as determinants of demographic trends and community health. These complex challenges require collective reflection and multi-sectoral solutions, extending beyond individual concerns. Proposed changes included urban improvements and new housing construction. Table 4 shows advancements in both areas by the project’s end.

Table 4. Proposals or solutions identified by the study, including those enacted and those still pending.

| Meta Categories | Proposals for Change Identified by Participants (After Feedback and Discussion with the Community) | Proposals for Change, Enacted and Pending (*) |

|---|---|---|

| Population | – Promote services, improve landscaping and housing | – Improvement to the central plaza and its surroundings in Mañaria (based on a project budgeted with participation of children in the community)—January 2017 – Inauguration of the Natural Sciences Museum “Hontza Museoa”—October 2014 – General Plan for Urban Layout (initially approved in June 2018), considering moderate urban growth involving between 50 and 60 new dwellings (*) |

| Domestic and community economy | – Include younger generations in domestic spaces – Foster small businesses – Continue supporting auzolana |

– Opening a hosting business—June 2018 – Annual auzolana sessions—2014–2019 – Joint participatory budgeting to integrate citizens in official budgeting process in the priority decision-making process—2012–present |

| Public and private spaces | – Promote healthy environments and resources | – Increase offer of public transportation to link the community with the cities of Durango and Bilbao—December 2014. – Increase frequency of public transportation offer to link the community with the cities of Durango and Vitoria—December 2018 |

| Life habits and lifestyle | – Foster physical activity | – Begin offering gymnastics exercise for open population—January 2014 – Restoration of the ball game (fronton) to increase sports offering to the community—May 2019 |

| Socializing process | – Foster community integration – Promote individual aspects that lead to a healthy socializing process |

– A group of parents organized the Andra Mari Association (2016), which organizes activities to allow children to stay in the community, enjoying leisure and free time activities – Offer of a cultural space and locale for adolescents (based on a participatory budgeting project that involved youngsters)—2016 – Increased offering of capacity-building sessions, including activities such as skating, robotics, bicycle maintenance, social networks, etc.—2017–19 |

| Health care resources | – Promote health care processes for men – Train agents for informal care – Offer pediatric services |

– Mobilization to restore an emergency pediatrics office in the clinic at Duranguesado—2017 – Offer of training sessions to care for back pain, pelvic floor, experiences of death for children, how to address sexuality, first aid for parents and kids—2016–2019. |

(*) Proposals marked with an asterisk were not yet implemented when the study was concluded.

3.3.2. From Home to Community Economics

Women identified three types of work contributing to individual, domestic, and community economic well-being. (1) Non-remunerated work, characterized by diverse tasks and personal, family, and social impacts, was primarily carried out by women, highlighting their role in reconciling work and domestic life. (2) Remunerated labor provided psychological, social, and basic needs fulfillment. (3) Auzolana, community participatory work, strongly present in Mañaria, fostered collaboration and non-remunerated community benefits. Strengthening auzolana was emphasized, leading to annual planning meetings initiated in 2014 and ongoing. Citizen participation in local budget decisions was also proposed and implemented.

3.3.3. Public and Private Spaces

Public and private spaces, where daily life unfolds, were considered significant health determinants. The rural character of Mañaria was valued for its quality of life compared to urban centers. However, public space concerns included quarries, roads (especially the main highway), and building issues. Private space concerns related to comfort, accessibility, peacefulness, safety, overcrowding, building maintenance, and neighborly coexistence. Improved public transport frequency and expanded schedules to nearby cities were requested and implemented after December 2018.

3.3.4. Habits and Lifestyles

This category encompassed daily life organization and habits. Eating habits reflected traditions, geographic environment, and food availability. Home cultivation of vegetables and family meals were positive aspects. Lower fish consumption compared to meat was identified for potential improvement. Alcohol consumption was mainly social, on weekends, with beer and wine preferred. Smoking habits were analyzed through smokers and ex-smokers’ experiences. While most informants reported sufficient sleep, some experienced rest-related problems. Leisure and free time activities were recognized as beneficial for physical, psychological, and social well-being, and regularly practiced. Promoting physical activity was proposed, leading to municipal gym spaces in 2014 and outdoor exercise areas approved in 2019.

3.3.5. Socializing Process

This category identified formal (school, childcare) and informal (church, cultural centers, public squares) settings fostering community socialization and personal development. Improving community integration and enabling healthy socializing processes were prioritized. Since 2016, initiatives included local leisure activities for children, cultural spaces for adolescents, and increased participatory activities like informatics and robotics.

3.3.6. Health Care Resources

Many women provided informal care to family members, serving as primary health care managers. Community care for the elderly was viewed positively, with families and social networks playing key informal care roles. However, loneliness among some elderly members was also noted. Formal health care was provided by a local doctor’s office with a physician and nurse, offering home visits and efficient, kind service. Areas for improvement included pediatric services, closer pediatric emergency care, expanded office hours, team coordination, more procedures like blood draws, and community activities. Proposals included health education sessions by professionals, implemented since 2014. Improving access to pediatric emergency services in a nearby locality remained a future objective.

4. Discussion

This community diagnosis definition approach, rooted in social determinants of health, emphasizes a comprehensive, multidimensional view of community life. Empowering women in health protection, promotion, and self-care, and fostering dialogue between health institutions and women were central. While others have used comprehensive approaches to health determinants [[8](#B8-ijerph-18-09661), 9], this study innovatively integrated theoretical approach with women as not just informants but research leaders. Women’s nuanced insights and suggestions were incorporated into study results, validated, and presented to the community and government, leading to tangible action.

Participant empowerment to co-lead the diagnosis and negotiate implementation is a key strength, aligning with a gender-sensitive approach in primary health care [[37](#B37-ijerph-18-09661), 38, 39]. Regional health plans for the Euskadi region [[40](#B40-ijerph-18-09661), 41], emphasizing community action in health, supported this strategy. Early involvement of local authorities, regular feedback, and report dissemination fostered credibility and action. Convergence of government and participant interests, facilitated by researchers, enabled proposal enactment.

Rural location significantly shaped the community diagnosis. Renewed value for rural living, offering nature and tranquility, contrasted with urban stress. However, limited public services hinder rural development. Political support for overcoming service limitations is crucial. The quarry industry’s negative impact on Mañaria’s health was significant, leading to community action and the closure of one quarry (Zalloventa), a major community improvement.

The importance of community sense and shared activities emerged strongly. Public spaces were seen as crucial for individual and community well-being, fostering safety, tranquility, and trust. Auzolana was identified as a powerful tool for social cohesion and achieving common goals efficiently [[42](#B42-ijerph-18-09661)]. While community activity in health promotion is researched [[43](#B43-ijerph-18-09661), 44], auzolana‘s role in community participation is a novel finding.

Methodologically, qualitative methods were effective for community health diagnosis [[13](#B13-ijerph-18-09661), 21]. Participant observation, while potentially biased, was mitigated by the researcher’s long-term community residence and local language proficiency, enabling deep integration and contextual understanding. The study’s extended duration, including validation, community engagement, and implementation, linked diagnosis to action.

Focusing solely on women informants might have missed male perspectives. While women highlighted their caregiving roles and community contributions, male viewpoints might have identified different problems and solutions. This study intentionally prioritized women’s perspectives, recognizing their crucial role in community health, aligning with previous research [[13](#B13-ijerph-18-09661), 15] and the importance of women’s empowerment [[46](#B46-ijerph-18-09661)].

The study identified health assets [[45](#B45-ijerph-18-09661)], including healthy environments, resources, community activities, and engaged professionals. Integrating health assets into the community diagnosis definition is a novel and valuable contribution, enhancing community health understanding. Prior studies on health assets [[45](#B45-ijerph-18-09661), 47] often focus solely on assets, without integrating them into a broader diagnostic framework.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, qualitative data collection is essential for effective community diagnosis, emphasizing a holistic view and incorporating women’s perspectives as active participants in problem-solving. Validation with informants refines findings and facilitates solution-seeking. This approach, encompassing health services, environment, urban, and sociocultural improvements, can be replicated, expanding the knowledge base for community health action.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to all study participants and contributors, and to the Mañaria town hall for their support. Special thanks to Carole Bernard for manuscript editing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V.; methodology, M.J.A.-E., E.R.-V. and H.M.; software, M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V.; validation, H.M., M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V.; formal analysis, M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V.; investigation, M.J.A.-E.; data curation, M.J.A.-E.; writing—review and editing, H.M., M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V.; supervision, H.M., M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V.; project management, H.M., M.J.A.-E. and E.R.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of UNIVERSIDAD PÚBLICA DEL PAÍS VASCO-EUSKAL HERRIKO UNIBERTSITATEA (protocol number CEISH/80/2011, on 12 September 2011).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available in deference to participants, who were not informed that their replies, even when de-identified, would be made publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[References]

Associated Data

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available in deference to participants, who were not informed that their replies, even when de-identified, would be made publicly available.