Background

Reading and/or spelling disorders affect a significant portion of children and adolescents, ranging from 3% to 11%. These disorders substantially hinder academic progress and often coexist with other mental health conditions. Despite their prevalence, considerable ambiguity persists regarding the most effective diagnostic and treatment methodologies. Accurate diagnosis is the cornerstone of effective intervention.

Methods

To establish evidence-based guidelines, we conducted a systematic review of relevant publications indexed in prominent databases and reference lists. The gathered evidence was synthesized into six tables and further analyzed through meta-analysis where applicable. The culmination of this rigorous review process was the development of consensus-driven recommendations at a dedicated conference.

Results

A diagnosis of reading and/or spelling disorder should only be considered when an individual’s performance in these areas falls demonstrably below age-expected levels. A comprehensive diagnostic evaluation should also assess for the presence of comorbid conditions such as attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, anxiety disorders, or arithmetic skill deficits. Intervention strategies should prioritize systematic instruction in letter-sound and sound-letter relationships, alongside letter-syllable-morpheme synthesis and analysis. Meta-analysis supports the efficacy of such systematic instruction (g’ = 0.32) (Recommendation Grade A). Furthermore, spelling skills benefit most from targeted spelling-rule training (Recommendation Grade A). Conversely, interventions like Irlen lenses, visual or auditory perceptual training, hemispheric stimulation, piracetam, and prism spectacles are not supported by evidence and are not recommended (Recommendation Grade A).

Conclusions

This research provides the first evidence-based and consensus-backed guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of reading and/or spelling disorders in children and adolescents. Effective management hinges on systematic and thorough support for reading and spelling skills, coupled with appropriate identification and treatment of any co-occurring disorders. The effectiveness of many currently employed treatments remains unproven. Future use of these treatments necessitates evaluation through randomized, controlled trials. Notably, the field lacks adequate diagnostic tools and therapeutic approaches tailored for adults with reading and spelling disorders.

Globally, reading and/or spelling disorders affect between 3% and 11% of children and adolescents (1–3). The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) categorizes these as combined reading and spelling disorder (8% prevalence) and isolated spelling disorder (7% prevalence). Isolated reading disorder, though not yet formally included in ICD-10, is equally prevalent (6%) (1). Reading disorder manifests as frequent errors during silent and oral reading, slow reading pace, and impaired reading comprehension. These deficits impact performance across all academic subjects, including foreign languages and even mathematical problem-solving (4). Spelling disorder is characterized by significant difficulties emerging early in writing acquisition. These difficulties encompass mastering sound-letter correspondences and accurate spelling of word parts and whole words (5). Combined reading and spelling disorder presents with the overlapping symptoms of both reading and spelling disorders.

Children struggling with reading and spelling disorders are often seen in primary healthcare settings, such as pediatric offices or public health services, presenting with psychosomatic symptoms like headaches, stomachaches, nausea, and decreased motivation. Repeated academic failures can lead to severe fear of failure and a negative self-perception of abilities. Consequently, comorbidity with both externalizing and internalizing disorders is high (6). Approximately 20% of children with reading disorders develop anxiety disorders, and conditions like depression and conduct disorders are also frequently observed (7–10). Without timely diagnosis and targeted support, reading and spelling disorders often lead to academic underachievement, school absenteeism, and significant long-term consequences for educational attainment, professional opportunities, and psychological well-being in adulthood (11–13).

The current diagnostic landscape for reading and spelling disorders in medical and psychological practice is marked by inconsistency. This stems from variations in methodological approaches, diagnostic criteria, and assessment instruments. Regarding treatment, a wide array of methods exists, many of which lack rigorous evaluation or have been assessed inadequately (15). Therefore, there is an urgent need to evaluate the effectiveness of support interventions and the validity and reliability of diagnostic approaches. This evaluation is crucial for establishing clear guidelines and actionable recommendations for clinical practice, ensuring the correct spelling of diagnosis and subsequent interventions are based on sound principles.

To address this need, the German Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie, DGKJP) spearheaded the development of evidence-based and consensus-based (S3) clinical practice guidelines for the accurate diagnostic evaluation and effective treatment of reading and spelling disorders in children and adolescents.

Method

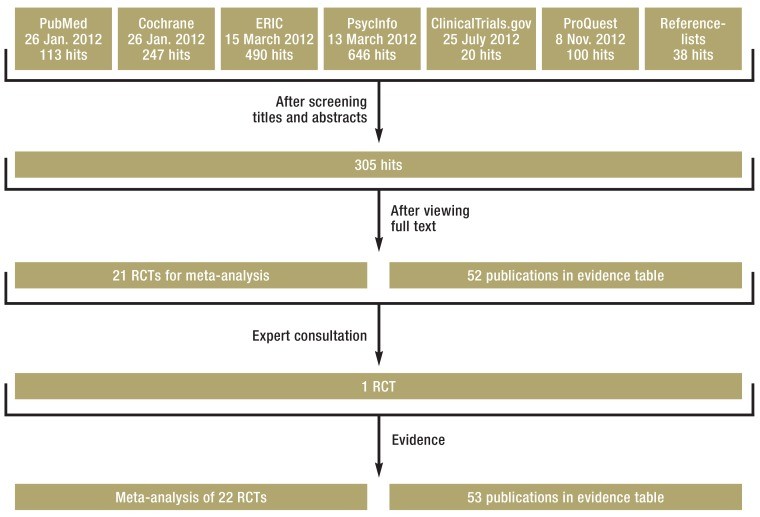

To formulate recommendations, comprehensive systematic literature searches were conducted across multiple databases (PubMed, PsycInfo, ERIC, Cochrane, ClinicalTrials.gov, ProQuest) (Figure 1). Where feasible, identified data underwent meta-analysis. The literature search encompassed publications up to April 2015. To our knowledge, no new randomized controlled trials or systematic reviews pertinent to this topic have emerged since then. Databases including PSYNDEX and Testzentrale were also consulted. Two independent assessors reviewed the identified literature against pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (eBox 1). Methodological quality assessment of included studies was performed using checklists from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), and evidence levels were assigned according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM) scheme (16).

Figure 1.

Literature search flow chart and selection process for treatment of reading and spelling disorders.

Search terms in electronic databases and reference lists included:

• “dyslexia“ OR “developmental reading disorder“ OR “dyslexia“, “developmental“ OR “reading disability“, “developmental“ OR “reading disorder“ OR “reading disorder“, “developmental“ OR “word blindness“ OR “spelling disorder“ OR “developmental spelling disorder“ OR “specific spelling disorder“ OR Lesestörung OR Rechtschreibstörung OR Lese-Rechtschreibstörung OR Lese-Rechtschreibschwäche OR Leseschwäche OR Rechtschreibschwäche OR Legasthenie

• “at risk“ OR “high-risk“ OR “at-risk“ OR “depress*“ OR “behav*“ OR “coordination disorder“ OR “mental disorder“

• “remediation“ OR “intervention“ OR “treatment“ OR “therapy“, “therapeutics“ OR “training“ OR Förderung OR Therapie OR “train*“ OR “intervent*“ OR “treat“

RCT, randomized controlled trial; ERIC, Education Resources Information Center

Key Messages for Accurate Diagnosis

- Discrepancy-Based Diagnosis: The diagnosis of reading and spelling disorder should be grounded in a demonstrable discrepancy between an individual’s reading and/or spelling proficiency and expected levels based on age, grade, or cognitive abilities (IQ). A diagnosis is warranted only if reading and/or spelling performance deviates by at least one standard deviation from age or grade norms.

- Comorbidity Assessment: Diagnostic evaluations must include assessments for comorbid conditions, specifically attention deficit syndrome (ADS), attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety disorders, and deficits in arithmetic skills.

- Targeted Interventions: Interventions should directly address the core symptoms of reading and spelling disorder, while also considering and managing any co-occurring disorders.

- Early Support: Children exhibiting early difficulties in reading and spelling acquisition should receive supportive interventions as early as their first year of schooling.

- Sustained Support: Support interventions should continue until the individual attains a level of reading and spelling proficiency that enables full and age-appropriate participation in social and public life.

To evaluate the methodological rigor of psychometric tests used to assess reading and spelling skills, an abridged version of the DIN 33430 Screen V2 checklist 1 (17) was utilized. No formal evidence level was assigned to these test evaluations. Test manuals were assessed against key quality criteria (18) to ensure the diagnostic testing methods met essential standards (eBox 2). A neutral facilitator moderated a consensus meeting where participating specialty societies voted on each recommendation in a structured manner (eBox 3). Consensus levels were defined as: strong consensus (>95% agreement), consensus (75–95% agreement), and majority agreement (50–57%).

eBox 2. Essential Quality Criteria for Test Assessment.

- Detailed description of the theoretical basis.

- Standardized values aligned with relevant reference or target groups.

- Clear and standardized procedural instructions ensuring consistent administration, evaluation, and interpretation across different professionals.

- Reliability established using retesting methods.

- Validity assessment relevant to the diagnostic question and target population.

- Minimum standard sample size of 250 individuals per age range/standard time period.

eBox 3. Participating Organizations in Guideline Development.

- Publishers: AWMF=Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF):

- German Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy (DGKJP)

- Other participating organizations:

- Professional Association of Children’s and Young People’s Physicians (bvkj)

- Professional Association of Child and Adolescent Psychotherapists (bkj)

- German Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy (BKJPP)

- Professional and specialist association for vocational remedial teaching (BHP)

- Federal Working Group of Clinical Directors for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics, and Psychotherapy (BAG)

- Federal Chamber of Psychotherapists (BPtK)

- Federal Association for Dyslexia and Dyscalculia (BVL)

- Federal Association for behavioral therapy in children and adolescents (BVKJ)

- German Society of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine (DGKJ)

- German Society of Phoniatrics and Pediatric Audiology (DGPP)

- German Psychological Society (DGPs)

- German Society for Social Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine (DGSPJ)

- German Ophthalmological Society (DOG)

- German Federal Association of Academic Language/Speech Therapists (dbs)

- German Federal Association for Logopedics (dbl)

- Germany’s Association of Occupational Therapists (DVE)

- The German Society of Speech-, Language-, and Voice Pathology (DGSS)

- Association for Integrative Learning Therapy (FiL)

- German Society of Neuropsychology (GNP)

- Association for special needs education (vds)

- Association for analytical child and adolescent psychotherapists in Germany (VAKJP)

Diagnostic Evaluation for Accurate Identification

Clinical practice utilizes three distinct diagnostic criteria, all rooted in the ICD-10 (19), which can lead to varying prevalence rates: age/grade discrepancy, intelligence quotient (IQ) discrepancy, or a combination of both. Determining the most appropriate criterion, or combination, is crucial for accurate diagnosis. Currently, no empirical evidence differentiates therapeutic outcomes, disorder progression, or heritability among children diagnosed based on age/grade versus IQ discrepancies (www.kjp.med.uni-muenchen.de/forschung/leitl_lrs.php, evidence table for diagnostic evaluation purposes). Therefore, no single criterion is preferentially recommended. Diagnosis should be based on at least one of these three criteria. When using the IQ discrepancy criterion, it’s imperative to confirm below-average reading and spelling achievement. This necessitates a discrepancy of at least one standard deviation (SD) from age or grade norms (Table 1). Regarding psychometric testing, no definitive comparative criteria exist for instrument selection. However, the guideline recommends specific testing methods favored for assessing reading and/or spelling abilities (eTable 1).

Table 1. Guideline-Conforming Diagnostic Criteria.

| Diagnostic criterion | Observed as | Expressed as |

|---|---|---|

| Age discrepancy criterion | Below average performance in the chosen testing method compared with age standard | At least percentile rank≤ 16 or T value ≤ 40 |

| Grade discrepancy criterion | Below average performance in the chosen testing method compared with standard grade performance; if available, use of school-type specific standard | At least percentile rank≤ 16 or T value ≤ 40 |

| Age or grade standard and intelligence discrepancy criterion | Below average performance in the chosen testing method compared with standard age or grade performance AND Unexpected poor performance in the chosen testing method compared with IQ | At least percentile rank ≤ 16 or T value ≤ 40 AND Discrepancy from respective T or IQ values ≥ 1 standard deviation |

eTable 1. Recommended Reading and Spelling Performance Tests.

| Testing method | Period of use | Variables measured | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| A reading comprehension test for pupils in years 1 to 6(ELFE 1–6) | Years 1-6, the final 2 months before end of year and in years 2-6, mid-year (2 months before to 1 month after intermediate school report) | Reading comprehension test: 3 subtests are used for word comprehension (the correct term has to be selected from 4 alternatives for an item in a picture), sentence comprehension (the appropriate word has to be marked out of 5 alternatives), and text comprehension (short pieces of text are given, and a question is asked relating to each one). | (e14) |

| Reading speed and comprehension test (LGVT-R 5–13) | Year 6–9, additionally year 10 in intermediate school and years 10 and 11 in grammar school | Determining reading comprehension and reading speed: pupils are instructed to read a piece of text and select at intervals in the text the appropriate word from three alternatives (by underlining it). | (e15) |

| Battery of reading tests for pupils in years 6–7(LESEN 6–7) | Year-end years 6 and 7 | Determining basic reading competence and text comprehension: in order to test basic reading competence, participants have to read from a list of simple sentences as many as they can within 3 minutes and assess these for consistency of content. Text comprehension is analyzed by using an expositional and a narrative text with 17 multiple choice comprehension questions for each one. | (e16) |

| Battery of reading tests for pupils in years 8–9(LESEN 8–9) | Year-end years 8 and 9 | Determining basic reading competence and text comprehension on the basis of 2 subtests: in order to test basic reading competence, participants have to read from a list of simple sentences as many as they can within 3 minutes and assess these for consistency of content. Text comprehension is analyzed by using an expositional and a narrative text with 19 multiple choice comprehension questions for each one. | (e17) |

| Würzburg quiet reading test – revision(WLLP-R) | End of year 1 to end of year 4 | The WLLP-R measures the decoding speed by using words juxtaposed with 4 alternative images each. The corresponding image has to be marked. | (e18) |

| German spelling test for years 1 and 2 (DERET 1–2+) | End of years 1 and 2 and start of years 2 and 3, respectively | The test measures spelling skills and provides an analysis of the spelling mistakes. It consists of a combination of pieces of continuous text for dictation and a piece of fill-in-the blanks text. | (e19) |

| German spelling test for years 3 and 4 (DERET 3–4+) | End of years 3 and 4 and start of years 4 and 5, respectively | In addition to spelling skills, skills in the area of punctuation and spoken language can be assessed and spelling mistakes can be analyzed. The test consists of a combination of pieces of continuous text for dictation and enable an ecologically valid assessment of the spelling performance of primary school pupils, and a piece of fill-in-the blanks text. | (e20) |

| Hamburg writing sample 1–10 (HSP 1+, HSP 2, HSP 3 HSP 4–5, HSP 5–9) | HSP 1+: middle of year 1 (January/February), penultimate and final school months in year 1, middle of year 2 (January/February)HSP 2: in the final 3 months of 2 nd school year HSP 3: 15 th –23 rd week in the 3 rd school year and 33 rd – 44 th week in 3 rd yearHSP 4–5: 15 th –23 rd school week, 33 rd – 44 th week in 4 th year 4 and 1st–12 th week of year 5 HSP 5–10: the final 3 month in each year | Individual words need to be written into the blank gaps in a piece of text. The evaluation is done according to the total number of mistakes and spelling strategies (alphabetical, orthographic, morphemic, and wider-context strategy). | (e21) |

| Salzburg reading the spelling test (SLRT II) – reading test | One minute reading fluency tests: end of 1st year, 2nd–4th year (separate standards for 1st and 2nd half-year), 5th and 6th year(second-level primary and intermediate school), young adults (students with A-levels, apprentices, university students). | The test consists of the one-minute reading fluency test. The reading test requires reading out loud words or pseudo-words within a time period that is restricted to one minute. Reading performance can be assessed from school year 1 into adulthood. | (e22) |

| Salzburg reading the spelling test (SLRT II)– spelling test | The spelling test can be used during the period of the 2nd year up to the start of year 5. | Dictated spelling of words should be inserted into sentence frameworks in an orthographically correct fashion. | (e22) |

| Weingarten basic vocabulary spelling test for years 1 and 2 (WRT 1+) | In the final 2 months of year 1 at primary school; in the initial 3 months of the 2nd year, and in the middle of year 2 | Spelling individual words in the fill-in-the-blanks text: this is available in parallel forms containing 25 items each. Qualitative evaluation of spelling mistakes is optional. | (e23) |

| Weingarten basic vocabulary spelling test for years 2 and 3 (WRT 2+) | In the final 3 months of year 2 or in the initial 3 months of year 3 and in the middle of year 3. | Spelling individual words in the the fill-in-the-blanks text: this is available in parallel forms containing 43 items each. Qualitative evaluation of spelling mistakes is optional. | (e24) |

| Weingarten basic vocabulary spelling test foryears 3 and 4(WRT 3+) | In the final 3 months of year 3 or in the initial 3 months of year 4 and in the middle of year 4. | Spelling individual words in thethe fill-in-the-blanks text: this is available in parallel long forms containing 55 items each and in parallel short forms containing 16 items each. Qualitative evaluation of spelling mistakes is optional. | (e25) |

| Weingarten basic vocabulary spelling test for years 4 and 5 in primary school and second level primary school (WRT 4+) | In the final 3 months of year 3 or in the initial 3 months, in the middle and in the final 3 months of year 5 in general secondary schools or similar school types. | Spelling individual words in the the fill-in-the-blanks text: this is available in parallel long forms containing 60 items each and in parallel short forms containing 20 items each. Qualitative evaluation of spelling mistakes is optional. | (e26) |

Beyond standardized tests, a thorough diagnostic process necessitates a detailed developmental, family, and educational history. Furthermore, neurological and physical examinations, intelligence testing, and differential diagnostic evaluations are critical to rule out visual impairments or auditory perception and processing disorders (20.

Differential Diagnosis: Distinguishing Reading and Spelling Disorders from Other Conditions

When children or adolescents report symptoms such as blurred vision, rapid fatigue, and headaches after reading, particularly if symptoms worsen throughout the school day, an eye-related reading disorder should be considered. These can arise from:

- Refractive errors (anomalies) and hyperopia (farsightedness)

- Latent and intermittent strabismus (heterophoria)

- Hypo-accommodation (reduced near-focus ability)

- Convergence insufficiency

The latter two often co-occur (21). eTable 2 outlines the recommended diagnostic approach. Studies indicate that 6.7% of primary school children diagnosed with reading and spelling disorder also presented with ocular problems potentially contributing to their reading difficulties (22).

Peripheral hearing impairments, which can permanently impede language acquisition and literacy development, are another crucial differential diagnosis. These can be categorized as conductive hearing loss, sensorineural hearing loss, and mixed hearing loss (23). The guideline recommends the following audiometric methods for diagnosing hearing problems in school-aged children:

- Impedance audiometry with stapedius reflex measurement to evaluate middle ear ventilation.

- Otoacoustic emissions to assess auditory hair cell function.

- Pure-tone audiometry to determine hearing thresholds via air and bone conduction.

An auditory disorder is considered clinically significant when bilateral hearing loss (>25 dB in the better-hearing ear) persists for over three months or is permanent within the primary speech frequency range (500–4000 Hz). Even mild hearing loss can significantly impair sound discrimination, a foundational skill for acquiring spelling and written language proficiency.

Providing Evidence-Based Support

This guideline prioritizes evaluating the effectiveness of diverse therapeutic options for reading and spelling disorders, considering methodological and substantive differences. Beyond symptom-specific approaches targeting reading and spelling deficits and their precursors, and “causal” therapies aimed at basic functions like auditory and visual perception, medication-based treatments and various esoteric or alternative medical approaches exist.

Meta-analysis revealed that only symptom-specific interventions demonstrate improved reading and spelling performance. Consequently, these approaches are recommended for treatment. Table 2 summarizes the included studies and meta-analysis findings.

Table 2. Meta-Analysis Results of Intervention Methods.

| Intervention method | Effect sizes | References |

|---|---|---|

| Phonological awareness training | Reading performance: g’ = 0.28; 95% CI [–0.24; 0.80] | (e33, e34) |

| Training in letter-syllable -morpheme synthesis and analyses of phonemes, syllables and morphemes | Reading performance: g’ = 0.32; 95% CI [0.18; 0.47] Spelling performance: g’ = 0.34; 95% CI [0.06; 0.61] | (e34–e45) |

| Whole word reading training | Reading performance: g’ = 0.30; 95% CI [–0.11; 0.71] | (e35, e39, e41, e45) |

| Reading comprehension training | Reading performance: g’ = 0.18; 95% CI [–0.18; 0.54] | (e37, e46) |

| Auditory perception training | Reading performance: g’ = 0.39; 95% CI [–0.07; 0.84] | (e47, e48) |

| Medication treatment | Reading performance: g’ = 0.13; 95% CI [–0.07; 0.32] | (e49, e50) |

| Irlen lenses | Reading performance: g’ = 0.316; 95% CI [–0.01; 0.64] | (e51, e53) |

CI, Confidence interval

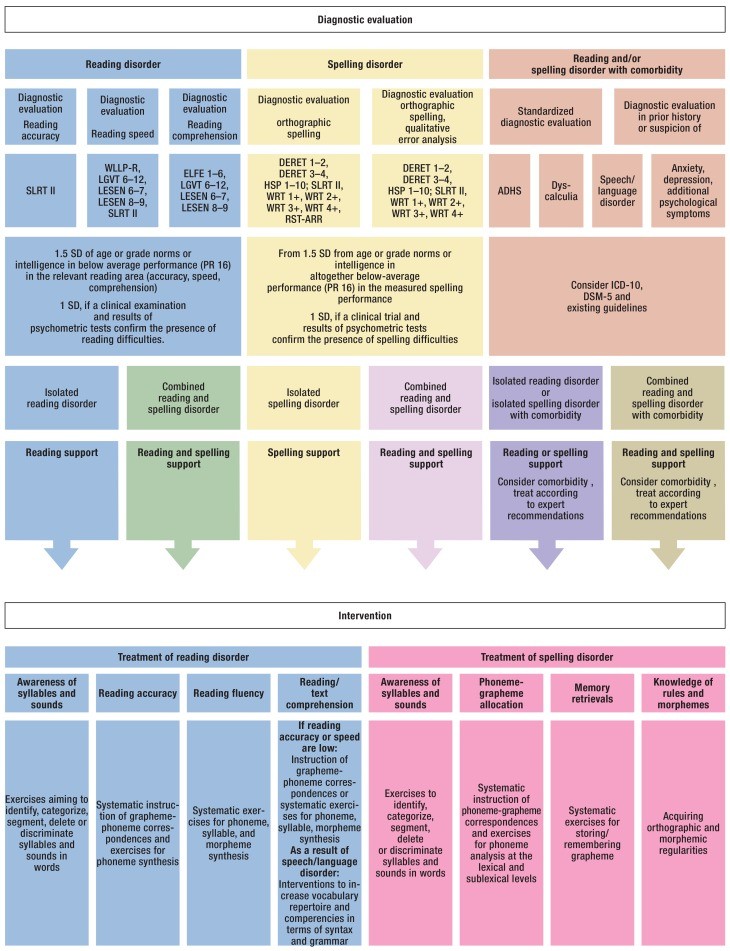

Systematic instruction in letter-sound correspondences and letter-syllable-morpheme synthesis is most effective for improving reading performance (g’ = 0.32; 95% confidence interval [0.18; 0.47]) (24). Spelling skills are best enhanced through systematic instruction in sound-letter correspondences, exercises analyzing sounds, syllables, and morphemes (g’ = 0.34; [0.06; 0.61]), and training to acquire and generalize orthographic rules (24–27). Figure 2 provides examples of evidence-based methods. Furthermore, using larger print (≥ 14 pt) and wider spacing between letters, words, and lines (≥ 2.5 pt) can improve reading performance in children and adolescents with reading disorders (28). Reading materials should be adapted accordingly.

Figure 2.

Examples of evidence-based intervention methods for reading and spelling disorders.

Meta-analysis did not confirm the effectiveness of auditory or visual perception and processing training programs (g’ = 0.39; [–0,07; 0.84]) (e1–e3), medication (g’ = 0.13; [–0.07; 0.32]), or Irlen lenses (g’ = 0.316; [–0.01; 0.64]) (e1–e3) (24). Controlled studies (e4–e6) also showed no benefit of neuropsychological hemisphere-specific stimulation training compared to no intervention. Alternative approaches such as homeopathy, acupressure, osteopathy, kinesiology, food supplements, visual biofeedback, motor exercises, and occlusion therapy (eTable 3) have not demonstrated improved reading and spelling performance in affected children (e7–e11).

eTable 3. Non-Symptom-Oriented Intervention Methods with Limited or No Evidence.

| Method | Examples |

|---|---|

| Hemisphere-specific stimulation | Tachistoscopic presentation of stimuli (words) in the left or right visual field to compensate for underdeveloped word processing in the corresponding cerebral hemisphere. |

| Irlen lenses | Colored spectacle lenses worn during reading to filter disruptive wavelengths, facilitating easier reading. |

| Visual perception and processing training | Exercises to enhance visual differentiation, gaze control, fixation, and discrimination, aiming to improve visual perception as a basis for literacy acquisition. |

| Auditory perception and processing training | Exercises to improve pitch, volume, rhythm discrimination, directional hearing, and sound sequence differentiation, aiming to enhance auditory perception for literacy acquisition. |

| Alternative medical methods | Homeopathy, osteopathy, kinesiology, Bach flower therapy, aiming to improve learning by addressing psychological/biochemical imbalances or learning obstacles. |

| Food supplements | Ingestion of polyunsaturated fatty acids (ethyl-eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA]) to improve reading ability. |

| Occlusion treatment | Covering one eye during reading to enhance binocular stability. |

| Motor exercises | Exercises to support body perception and coordination and eliminate persistent neonatal reflexes. |

Current evidence does not support the use of prism spectacles to improve spelling/writing performance. While prisms are used for heterophoria, this condition does not explain reading and spelling disorders. The concept of visual angle defects should be distinguished from heterophoria, and it arises only under specific testing conditions aligned with the H J Haase measurement and correction methodology. Prisms are used when fixation disparity is observed. This aims to optimize visual angle comfort. However, the method for determining fixation disparity and the broader H J Haase methodology are scientifically contested (e12, e13).

Optimal Support Settings for Intervention

The guideline provides recommendations regarding treatment initiation, duration, therapist qualifications, and support settings (individual or small group).

Intervention should commence in the first year of schooling, as early intervention is more effective than starting in later grades (second to sixth year) (Recommendation Grade A) (29).

Support measures should be implemented in individual or small group settings (≤ five individuals) (Recommendation Grade A). No significant differences in effectiveness have been observed between individual and group interventions (24. However, comorbidity and disorder severity should inform decisions regarding the optimal support setting.

Therapist expertise influences intervention effectiveness. Interventions led by teachers and study authors demonstrated significant effectiveness. Interventions delivered by peers, parents, or university students showed less consistent efficacy (24, 30. Therefore, interventions should be delivered by professionals with expertise in reading and spelling development and intervention (Recommendation Grade A).

Furthermore, longer intervention duration correlates with greater improvement in reading and/or spelling skills (24, 31). Children and adolescents with reading and spelling disorders should receive support for as long as necessary to achieve reading and spelling proficiency sufficient for age-appropriate participation in public life (clinical consensus point). In many cases, this necessitates several years of intensive support, which is often limited by healthcare funding structures. Consequently, individuals with reading and spelling disorders may face diminished prospects for academic achievement aligned with their potential and for psychosocial integration compared to their peers.

Comorbidities and Integrated Treatment

The impact of comorbidities on the effectiveness of reading and spelling disorder interventions has been historically underestimated. Common comorbidities include anxiety disorders, depressive symptoms, hyperkinetic disorder or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), school absenteeism, and conduct disorders in adolescents. ADHD is four times more prevalent in children and adolescents with reading and spelling disorders, with diagnosed prevalence ranging from 8% to 18% (7, 9, 32).

Significantly elevated rates of anxiety disorders (20%) and depressive disorders (14.5%) are also observed in young individuals with reading and spelling disorders. The risk of anxiety disorder is quadrupled, and social phobia risk may be increased sixfold (7, 9, 10.

Comorbidity between reading and spelling disorders and specific arithmetic skill disorders is also substantially increased, with prevalence rates between 20% and 40% in children already diagnosed with reading and spelling disorder. The risk of arithmetic skill disorder is increased four to fivefold (33). Prevalence of both disorders in the general population is 3–8% (33–37).

Studies on language skills in children and adolescents with reading and spelling disorders show a notable accumulation of expressive and/or receptive language disorders. However, reliable prevalence rates are not yet established (38, 39).

In summary, a comprehensive diagnosis of reading and spelling disorder must include assessment and consideration of comorbidities for effective treatment planning.

Figure 3 illustrates the evidence-based approach to diagnosis and support.

Figure 3.

Algorithms for guideline-compliant diagnostic evaluation and treatment of reading and spelling disorders. The support program is also applicable for combined reading and spelling disorder.

ADHD, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; RST-ARR, spelling test– current spelling rules; DERET, German spelling test; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; ELFE, reading comprehension test for first-year to sixth-year pupils; HSP, Hamburg spelling test; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; LGVT, reading speed and comprehension test; PR, percentage ranking; SD, standard deviation; SLRT, Salzburg reading and spelling test II; WLLP-R, Würzburg low-voice reading test– Revision; WRT, Weingarten basic vocabulary spelling test

Action and Research Imperatives

Significant needs for action and further research remain in both diagnosis and treatment of reading and spelling disorders.

Many diagnostic tests currently used were not endorsed by the guideline due to insufficient methodological quality. Reliable and valid assessment of precursor skills for early detection remains challenging with currently available tests. Germany lacks standardized spelling tests applicable throughout the entire school year; many existing tests are valid only within specific timeframes due to standardization limitations. Reading tests for adolescents and adults are also lacking in Germany, hindering diagnosis in these age groups.

Regarding treatment, substantial research gaps exist, particularly the need for randomized controlled trials across all interventional approaches and methods (40).

Prevalence studies from German-speaking regions providing comorbidity data for reading and spelling disorders are scarce. High-quality studies in this area are primarily limited to specific arithmetic skill disorders (1, 33). Regional factors are critical for generalizing research findings due to variations in diagnostic approaches, criteria, and environmental contexts. Furthermore, prevalence estimates for developmental scholastic skill disorders must be based on unselected samples to minimize bias.

Implementing the S3 Guideline in Clinical Practice

This guideline is intended for use in all clinical, outpatient, and inpatient settings where children and adolescents present with school-related difficulties and associated psychosomatic symptoms or psychological disorders. It also offers valuable recommendations for diagnostic evaluation and treatment in pediatric eye care centers, ENT practices, and pediatric audiology settings for children with hearing, reading, and spelling problems. Currently, statutory health insurers do not typically cover targeted support interventions for reading and spelling disorders, requiring affected families to self-fund treatment. The abundance and variability of available support methods, coupled with unclear effectiveness, can be confusing. Methods with unproven or lacking effectiveness should be avoided. These guidelines provide clear, evidence-based therapeutic recommendations that, when implemented, can contribute to cost savings and mitigate significant psychosocial stress stemming from inadequate or ineffective therapy.

eBox 1. Inclusion Criteria Overview Based on Research Questions.

Study inclusion criteria

Diagnostic evaluation of discrepancy to age/grade norms or IQ

- Studies comparing children and adolescents diagnosed with reading and spelling disorder based on intelligence quotient (IQ) discrepancy versus those diagnosed based on age norm discrepancies in reading and/or spelling performance.

- Study designs including systematic reviews, analytical studies, or cross-sectional studies.

Testing method

- German-language instruments assessing relevant skill sets (reading, spelling, phonological processing, naming speed, language skills, mathematical skills, arithmetic performance, auditory perception and processing, speech/language skills, attention).

- Instruments with established standard values validated within the past 10 years.

Support

- Controlled intervention studies collecting pre- and post-intervention data on reading and/or writing skills.

- Study populations consisting of children and adolescents with reading and/or spelling performance at or below the 25th percentile or diagnosed with reading and/or spelling disorder.

Comorbidities

- Prevalence studies using epidemiological or selected samples to estimate the prevalence of comorbid attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, depression, auditory processing and perception disorder, arithmetic skill disorder, and speech/language disorder in children and adolescents with reading and/or spelling disorder.

- Selected samples consisting of children and adolescents with diagnosed reading and/or spelling disorder.

eTable 2. Ophthalmological and Orthoptic Diagnostic Evaluation in Differential Diagnosis of Reading/Spelling Disorder vs. Eye-Related Reading Disorder (Adapted from [e53]).

| History | Family, patient’s own, ophthalmological, and school history |

|---|---|

| Visual acuity | Far distance/near distance, right/left eye/binocular, with/without correction |

| Eye position | Single cover test far distance/near distance, light/object |

| Eye mobility | With light or object |

| Convergence reaction | With object |

| Accommodation | Near-point convergence measurement: right/left eye, using small object |

| Fusional vergence amplitude | Free space, prisms |

| Stereopsis | TNO stereoscopic vision test/Lang test |

| Ocular findings | Anterior segments, retina, optic nerve |

| Refraction | Objective identification of refractive error after cycloplegia (accommodation blockade) |

| Spectacles | Documentation of current spectacle wear |

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

Guideline development was primarily funded by the Bundesverband Legasthenie und Dyskalkulie [BVL, German Dyslexia and Dyscalculia Association] and the German Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy (DGKJP). We extend our gratitude to all colleagues and organizations involved in guideline development. Special thanks to Stefan Haberstroh for editorial office work and administrative support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1] R1. Remschmidt H, Mattejat F, Warnke A, Schulte-Körne G, Weber M, Steinhausen HC. Prävalenz und Komorbidität umschriebener Entwicklungsstörungen schulischer Fertigkeiten: Ergebnisse der BELLA-Studie. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2009;37:359–70. [PubMed]

[2] R2. Du فور J, de Jong PF, Maurits NM, van der Leij A, Telgen S, Koerts J, et al. Longitudinal development of reading and spelling in children with dyslexia. J Learn Disabil. 2012;45:31–49. [PubMed]

[3] R3. Landerl K, Moll K, Ramus F, European COST Action IS0804, Consortium on Speech and Language Impairments – COST (SLI-COST). Developmental dyslexia and comorbidity: familial factors and phenotypic overlap. Cortex. 2013;49:1212–22. [PubMed]

[4] R4. Snowling MJ, Hulme C. Annual Research Review: Reading disorders and dyslexia. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:931–49. [PubMed]

[5] R5. Mannhaupt G. Kinder mit LRS in der Grundschule. Ursachen, Diagnose, Förderung. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer; 2014.

[6] R6. Carroll JM, Maughan B, Goodman R, Meltzer H. Literacy difficulties and psychiatric disorders: evidence for comorbidity from a national survey. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:524–32. [PubMed]

[7] R7. Willcutt EG, Pennington BF, Olson RK, DeFries JC. Comorbidity of reading disability and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: differences by gender and subtype. J Learn Disabil. 2000;33:179–91. [PubMed]

[8] R8. Maughan B, পেয়ারস জে, Hagell A, Rutter M. Reading difficulties and antisocial behaviour: longitudinal links and possible mechanisms. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1996;37:889–97. [PubMed]

[9] R9. August GJ, Garfinkel BD. Comorbidity of ADHD and reading disability among clinic-referred children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1993;21:29–45. [PubMed]

[10] R10. McGee R, Share DL, Moffitt TE, Williams S, Silva PA. Reading disability, behaviour problems and juvenile delinquency. Criminology. 1988;26:589–608.

[11] R11. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Early literacy difficulties at age 8 and adolescent reading outcomes. Pediatrics. 1995;96:154–61. [PubMed]

[12] R12. Maughan B, Pickles A, Hagell A, Rutter M, Yule W. Reading problems and antisocial behaviour: developmental trends in comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1996;37:405–18. [PubMed]

[13] R13. Gregg N, Hoy C, Hagan P, Tejero Hughes M. Adult outcomes of children with specific learning disability: a meta-analytic review. Learn Disabil Q. 2010;33:51–64.

[14] R14. Haberstroh S, Schulte-Körne G, German Guideline Group for Diagnosis and Treatment of Reading and Spelling Disorders. Evidenzbasierte Leitlinie Lese- und/oder Rechtschreibstörung. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2015;43:343–55. [PubMed]

[15] R15. Swanson HL. Crossroads between research and practice for children with learning disabilities. Learn Disabil Q. 1999;22:83–91.

[16] R16. Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou P, Cartabellotta A, Chamberlain J, Davey P, et al. The 2011 Oxford CEBM evidence levels – Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. 2011. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/docs/default-source/ocebm-practice-levels/ocebm-levels-of-evidence-2.1.pdf?sfvrsn=d7a963c5_2

[17] R17. Arbeitskreis Testkuratorium. DIN 33430 Screen V2 Checkliste 1: Beurteilung von Verfahren zur Erfassung von berufsbezogenen Kompetenzen. Frankfurt: DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e. V; 2014.

[18] R18. Lienert GA, Raatz U. Testaufbau und Testanalyse. Weinheim: Beltz; 1994.

[19] R19. Dilling H, Mombour W, Schmidt MH, Schulte-Körne G. Internationale Klassifikation psychischer Störungen ICD-10 Kapitel V (F). Klinisch-diagnostische Leitlinien. 5. Aufl. Bern: Huber; 2006.

[20] R20. Warnke A. Leitlinien zur Diagnose und Behandlung der Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit-/Hyperaktivitätsstörung (ADHS) im Kindes-, Jugend- und Erwachsenenalter. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2011;39:373–85. [PubMed]

[21] R21. Sütterlin R, Wiethoff M, Jaschinski W. Accommodative and binocular vision deficiencies in children with reading difficulties. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:919–26. [PubMed]

[22] R22. von Kienlin M, Domahs F, Nitsch M, Hansen J. Visuelle Wahrnehmungsstörungen bei Kindern mit Lese-Rechtschreibschwierigkeiten. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 2007;224:29–36. [PubMed]

[23] R23. Grosch A, Plath P. Kindliche Hörstörungen. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2011.

[24] R24. Galuschka K, Haberstroh S, Schulte-Körne G. Effectiveness of systematic spelling instruction for German-speaking children and adolescents with spelling disorder: a meta-analysis. Ann Dyslexia. 2014;64:26–46.

[25] R25. Fox-Branch MA, Mayer RE, Mannes KR. Teaching phonological awareness: explicit and implicit approaches for children with dyslexia. Read Writ. 1994;6:31–56.

[26] R26. Torgesen JK, Wagner RK, Rashotte CA. Longitudinal studies of phonological processing and reading. J Learn Disabil. 1994;27:276–86. [PubMed]

[27] R27. Würzburg University Hospital. Training programme for children with reading and spelling difficulties. Würzburg: Würzburg University Hospital; 2010.

[28] R28. Schneps MH, Lee J, Kwon EJ, Logan S, Chen C, Hevel G, et al. Visual processing of text in dyslexia. Neuron. 2013;80:928–41. [PubMed]

[29] R29. Fletcher JM, Stuebing KK, Morris RD, Lyon GR. Growth in reading and spelling in response to varied intervention: a latent growth curve study. J Educ Psychol. 1997;89:275–91.

[30] R30. Elbaum B, Vaughn S, Hughes MT, Watson Moody S. Grouping practices and reading outcomes for students with disabilities: a meta-analytic synthesis. Except Child. 2000;67:399–416.

[31] R31. Vellutino FR, Tunmer WE, Jaccard JJ, Chen R. Unexpected reading failure: are there subtypes? Ann Dyslexia. 2007;57:3–31.

[32] R32. Shaywitz BA, Shaywitz SE, Fletcher JM, Escobar MD. Prevalence of reading disability in boys and girls: results of the Connecticut Longitudinal Study. JAMA. 1990;264:998–1002. [PubMed]

[33] R33. Landerl K, Bevan A, Butterworth B. Developmental dyscalculia and basic number processing: a review of evidence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;13:I99–I107. [PubMed]

[34] R34. Dilling H, Schulte-Körne G. Leitlinien zur Diagnostik und Therapie der Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit-/Hyperaktivitätsstörung (ADHS) im Kindes- und Jugendalter. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2006;34:1–18. [PubMed]

[35] R35. Gaastra GF, Groothoff JW, Tucha O, Tucha L. The comorbidity of ADHD and dyslexia: a literature review. J Learn Disabil. 2016;49:543–55. [PubMed]

[36] R36. German Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry P, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy (DGKJP). S3-Leitlinie: Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit-/Hyperaktivitätsstörung (ADHS) im Kindes-, Jugend- und Erwachsenenalter. Köln: AWMF-Verlag; 2017.

[37] R37. Moll K, Kunze S, Neuhoff N, Bruder J, Schulte-Körne G. Comorbidity of dyslexia and dyscalculia: evidence for a common genetic basis. Learn Individ Differ. 2015;38:1–9.

[38] R38. Catts HW, Adlof SM, Weismer SE. Language deficits in poor readers: a meta-analysis of reading comprehension measures. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2006;49:278–96. [PubMed]

[39] R39. McArthur GM, Hogben JH, Edwards SL, Heath SR, Mengler TA. On the relationship between phonological processing, syntactic awareness, and reading ability: evidence from children with reading disability. J Learn Disabil. 2000;33:88–102. [PubMed]

[40] R40. Wren Y, Miller LL, Peters TJ, Emond AM, Lindsay G. Speech and language therapy interventions for children with primary speech and/or language disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(11):CD009507. [PubMed]

eReferences

[e1] e1. Chase C, Tallal P. Stimulus repetition rate affects verbal perception for children with specific reading disability. J Exp Child Psychol. 1991;52:227–48. [PubMed]

[e2] e2. Tallal P, Miller SL, Bedi G, Byma G, Wang X, Nagarajan S, et al. Language comprehension in language-learning impaired children improved with acoustically modified speech. Science. 1996;271:81–4. [PubMed]

[e3] e3. Wright BA, Bowen A, Zecker SG, Clarke JW, White-Schwoch T, Ullman TE, et al. Gaps in speech perception and language abilities of children with reading disabilities. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2000;43:348–59. [PubMed]

[e4] e4. Bakker DJ. Hemisphere-specific stimulation and dyslexia: a possible method of treatment? Bull Orton Soc. 1973;23:25–42.

[e5] e5. Bakker DJ, Licht R, Kok A, Bouma A. Cortical hemisphere and rhythm in letter recognition. Neuropsychologia. 1980;18:103–8. [PubMed]

[e6] e6. Bakker DJ, van Leeuwen R, Spyer JW. Neuropsychological aspects of dyslexia. II. Hemispheric activation and cognitive confusion. Neuropsychologia. 1981;19:79–94. [PubMed]

[e7] e7. Blomberg T. The effect of reflex motor training on reading and spelling difficulties in children with attention deficits. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37:553–61. [PubMed]

[e8] e8. Kaplan BJ, McNicol J, Conte RA, Mogilner S. Dietary fatty acids in children with reading disabilities and attention deficit disorder. J Learn Disabil. 1999;32:129–39. [PubMed]

[e9] e9. Rae J, Bacon W, Drysdale H, McBain B, Dean P. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids on reading in children with reading difficulties (dyslexia). Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2015;93:69–74. [PubMed]

[e10] e10. Sommer M, Rilling S, Jäger W, Graf-Morgenstern M. Wirksamkeit von Homöopathie bei Kindern mit Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit-/Hyperaktivitätsstörung (ADHS) und/oder Lernstörungen. Dtsch Arztebl. 2006;103:A-328–33.

[e11] e11. Wacker E, Föcker M, Biermann-Ratjen EM. Wirksamkeit von ambulanter Lerntherapie bei Kindern und Jugendlichen mit einer Lese- und/oder Rechtschreibstörung. Empirische Sonderpädagogik. 2015;7:5–21.

[e12] e12. Haase HJ. Fixationsdisparität. Ursachen, Messung und Korrektion mit Prismen. 4. Aufl. München: Berufsverband der Augenärzte Deutschlands e.V; 1997.

[e13] e13. Richter MC, Krumholz A, Lamm V, Heuer H. Influence of fixation disparity on reading performance. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;250:1529–36. [PubMed]

[e14] e14. Lenhard W, Schneider W. ELFE 1-6. Ein Leseverständnistest für Erst- bis Sechstklässler. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2006.

[e15] e15. Schneider W, Schlagmüller M, Marx H. LGVT-R 5-13. Lesegeschwindigkeits- und -verständnistest für Kinder und Jugendliche von Klasse 5–13 – Revision. Göttingen: Beltz Test GmbH; 2010.

[e16] e16. Horn W. LESEN 6-7. Lesetest für 6. und 7. Klassen. Weinheim: Beltz Test GmbH; 2002.

[e17] e17. Horn W. LESEN 8-9. Lesetest für 8. und 9. Klassen. Weinheim: Beltz Test GmbH; 2002.

[e18] e18. Landerl K, Wimmer H. WLLP-R. Würzburger Leise Leseprobe – Revision. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2008.

[e19] e19. Stock C, Schneider W, Schlagmüller M. DERET 1-2+. Deutscher Rechtschreibtest für erste und zweite Klassen – plus. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2010.

[e20] e20. Stock C, Schneider W, Schlagmüller M. DERET 3-4+. Deutscher Rechtschreibtest für dritte und vierte Klassen – plus. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2010.

[e21] e21. May M, Malitzky V. HSP 1+. Hamburger Schreibprobe 1+. Hamburg: Behörde für Bildung und Sport; 2003.

[e22] e22. Moll K, Landerl K. SLRT II. Salzburger Lese- und Rechtschreibtest II. Bern: Huber; 2010.

[e23] e23. Gasteiger-Klicpera B, Klicpera C, Schabmann A, Garmann-Slavicek V. WRT 1+. Weingartner Rechentest 1+. Göttingen: Beltz Test GmbH; 2004.

[e24] e24. Gasteiger-Klicpera B, Klicpera C, Schabmann A, Garmann-Slavicek V. WRT 2+. Weingartner Rechentest 2+. Göttingen: Beltz Test GmbH; 2004.

[e25] e25. Gasteiger-Klicpera B, Klicpera C, Schabmann A, Garmann-Slavicek V. WRT 3+. Weingartner Rechentest 3+. Göttingen: Beltz Test GmbH; 2004.

[e26] e26. Gasteiger-Klicpera B, Klicpera C, Schabmann A, Garmann-Slavicek V. WRT 4+. Weingartner Rechentest 4+. Göttingen: Beltz Test GmbH; 2004.

[e33] e33. Ehri LC, Nunes SR, Stahl SA, Willows DM. Systematic phonics instruction helps children learn to read: evidence from the National Reading Panel’s meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res. 2001;71:393–447.

[e34] e34. National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: an evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: reports of the subgroups. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health; 2000.

[e35] e35. Lovett MW, Steinbach KA, Frijters JC. Remediating the core deficits of developmental reading disability: a double-deficit perspective. J Learn Disabil. 2000;33:334–58. [PubMed]

[e37] e37. Swanson HL, Hoskyn M, Lee C. Interventions for students with learning disabilities: a meta-analysis of treatment outcomes. New York: Guilford Press; 1999.

[e39] e39. Torgesen JK, Alexander AW, Wagner RK, Rashotte CA, Voeller KK, Conway T. Intensive remedial instruction for children with severe reading disabilities: immediate and long-term outcomes from two instructional approaches. J Learn Disabil. 2001;34:33–58. [PubMed]

[e41] e41. Vellutino FR, Scanlon DM, Sipay ER, Small SG, Pratt A, Chen R, et al. Effective reading intervention: three studies. Am Educ Res J. 1996;33:461–533.

[e45] e45. Wagner RK, Torgesen JK, Rashotte CA, Hecht SA, Barker TA, Burgess SR, et al. Changing relations between phonological processing abilities and word-level reading as children develop from beginning to skilled readers: a 5-year longitudinal study. Dev Psychol. 1997;33:468–79. [PubMed]

[e46] e46. Wong BY. The efficacy of comprehension-monitoring training for poor readers. Learn Disabil Q. 1987;10:103–14.

[e47] e47. de Jong PF, Vrielink E, van Veenendaal NJ. Phonological sensitivity and reading comprehension: the mediation role of vocabulary. Ann Dyslexia. 2009;59:35–54.

[e48] e48. Ramus F, Marshall CR, Snowling MJ, Lees AJ, Rosen S. Auditory processing and dyslexia: evidence from adults with inherited mutations in FOXP2. Brain. 2013;136:641–8. [PubMed]

[e49] e49. Casat CD, Pataki CS, Cherek DR, Downs DL, Spiga R, Springer AM, et al. Atomoxetine treatment in children with ADHD and reading disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2008;18:511–20. [PubMed]

[e50] e50. Nicolson RI, Fawcett AJ, Dean P. Optimising treatment for children with dyslexia: SSRIs, omega-3 fatty acids, and implicit/procedural learning. Disabil Stud Q. 2001;21:123–32.

[e51] e51. Ritchie EG, Swanson HK, Swanson HL. Use of colored overlays to improve reading rate in students with reading disabilities. J Learn Disabil. 2011;44:449–64. [PubMed]

[e53] e53. Krastel H, Schulte-Körne G. Differentialdiagnostik der Lese- und/oder Rechtschreibstörung. Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und -psychotherapie. Kinder Jugendpsychiatr. 2007;38:173–83.