Cotton-wool spots (CWS), also known as soft exudates, are critical indicators observed during retinal examinations. These spots are not diseases themselves but rather signs of underlying issues, often pointing towards systemic vascular problems. Though patients may not always experience immediate visual disturbances directly from these spots, their presence can be a harbinger of significant health conditions. For professionals in automotive repair or anyone interested in diagnostic processes, understanding the ‘cotton wool appearance’ in a medical context offers valuable insights into differential diagnosis—a process crucial in both medicine and mechanics. This article delves into the differential diagnosis of cotton wool spots, exploring their causes, associated conditions, and diagnostic approaches.

Historical Context and Terminology

Historically, cotton-wool spots were described in the mid-20th century as “soft masses of irregular shape, grayish-white appearance with fluffy margins,” typically located in the central retina, particularly near the optic disc. The term “soft exudates” is a misnomer as the characteristic whitening is not due to fluid exudation, although fluid leakage can be detected during fluorescein angiography. “Cotton-wool spot” is the currently preferred and accurate term.

Dollery described these spots as “a milky-white area of retina between 0.1 and 1 mm in diameter,” usually found near major retinal vessels in the posterior pole. He noted that hypertension-related CWS start as gray discolorations, becoming shiny white within a day or two.

The Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) Report 10 defined “soft exudates” as “localized superficial swellings in the nerve fiber layer,” characterized by a round or oval shape, white to grayish-white color, and feathery edges with striations parallel to nerve fibers. The ETDRS also developed a grading system for CWS based on their size.

Pathology of Cotton-wool Spots

The pathology of cotton-wool spots involves nerve fiber layer edema and the presence of “cytoid bodies.” These cytoid bodies are essentially bulb-like swellings at the ends of damaged nerve fibers. Wolter’s post-mortem studies confirmed these cytoid bodies as terminal swellings of damaged nerve fiber stumps. Cajal had previously described similar swellings in other parts of the nervous system, noting the general swelling in the nerve fiber layer around these bodies.

The formation process involves nerve damage leading to degeneration of the nerve section distal to the injury, while the proximal part develops a bulbous swelling. These swellings are an initial phase of nerve regeneration attempt. In the retina, while the proximal nerve survives for some time, it eventually degenerates as well. Some cytoid bodies may persist and become hyalinized.

Studies have indicated that capillaries within the CWS area either fail to fill or only partially fill, suggesting vascular occlusion. Capillaries surrounding the affected area often dilate and may show microaneurysms. Lipohyaline material buildup in vessel walls can contribute to occlusion.

Research using experimental models of ischemia, like microsphere embolization of retinal arterioles, showed nerve fiber swelling within just one hour of induced ischemia. Histology revealed three zones in each lesion: a central necrotic area flanked by swelling of the nerve fiber layer due to blocked axoplasmic flow. Over time, organelle and vesicle backup continued, and structural elements began to proliferate, interpreted as attempted regeneration. Fluid exudation in these models only occurred where the vessel wall was directly damaged.

Pathophysiology of CWS: Ischemia and Axoplasmic Flow Disruption

The primary theory behind the development of cotton-wool spots is the occlusion of precapillary arterioles, leading to localized retinal ischemia. The characteristic retinal whitening results from a halt in axoplasmic flow in both directions (orthograde and retrograde). Experimental models have consistently demonstrated this disruption of axoplasmic flow, leading to an accumulation of organelles, mitochondria, secretory vesicles, enzymatic vesicles, and other axoplasmic components. These accumulations are identified as cytoid bodies in pathological examinations. The leakage observed in fluorescein angiography is due to localized vascular damage and increased vascular permeability.

Mechanical forces can also play a role in CWS formation in certain rare scenarios. Axonal flow disruption might be caused by distortion of the nerve fiber layer and axon kinking. One study linked epiretinal membrane contraction to CWS formation, with spots resolving after membrane removal, suggesting mechanical force as the causative factor in these cases rather than ischemia.

Differential Diagnosis and Associated Conditions

The differential diagnosis of cotton-wool spots is broad, encompassing both ocular and systemic conditions. Ocularly, any retinal lesion that appears white or yellow-white must be considered. This includes acute retinal necrosis, progressive outer retinal necrosis, cytomegalovirus retinitis, toxoplasmosis, and other forms of posterior uveitis. Myelinated nerve fiber layer, retinal astrocytic hamartoma, and regressed retinoblastoma can also sometimes be mistaken for CWS.

Systemically, the differential diagnosis is even more extensive. Cotton-wool spots are non-specific and can be associated with a wide range of common and rare diseases. Essentially, any condition that can cause terminal arteriolar occlusion or localized hypoperfusion is in the systemic differential diagnosis.

Common systemic conditions associated with cotton-wool spots include:

- Vascular Diseases:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Arterial hypertension

- Central and branch retinal vein and artery occlusions

- Carotid artery occlusion

- Ischemic optic neuropathies

- Infections:

- HIV infection/AIDS

- Septicemia

- Leptospirosis

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever

- Cytomegalovirus retinitis

- Toxoplasmosis

- Onchocerciasis

- Immune and Collagen Vascular Diseases:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Dermatomyositis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Polyarteritis nodosa

- Scleroderma

- Wegener’s granulomatosis

- Giant cell arteritis

- Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia

- Embolic Phenomena:

- IV drug abuse

- Endocarditis

- Carotid artery plaques

- Cardiac valvular disease

- Purtscher and Purtscher-like retinopathy

- Trauma (long bone fractures, blunt chest trauma)

- Pancreatitis

- Hypercoagulability or hyperviscosity syndromes

- Homocysteinuria

- Protein C or S deficiency

- Anti-thrombin III deficiency

- Sickle cell disease

- Malignancy:

- Leukemia

- Metastatic carcinoma

- Lymphoma

- Other Causes:

- Papillitis

- Papilledema

- Transient hypoperfusion

- Severe anemia

- High altitude retinopathy

- Radiation retinopathy

- Epiretinal membrane

It is crucial to recognize the strong association between CWS and systemic vascular diseases. Studies show that a significant majority of patients presenting with new cotton-wool spots have an underlying systemic disorder upon evaluation. Diabetes and hypertension are particularly prevalent, even in individuals not previously diagnosed. For instance, in one case series excluding known diabetics, undiagnosed diabetes, hypertension, and collagen vascular diseases were the most common findings. It is also important to note that fasting glucose levels can be normal in patients with diabetes presenting with CWS, highlighting the need for glucose tolerance testing in diagnostic workups. Arterial hypertension associated with CWS is often acute and severely elevated, making blood pressure measurement a key diagnostic step.

Morphological Differences in CWS

Given the diverse conditions linked to cotton-wool spots, understanding morphological variations can aid in differential diagnosis. Studies have attempted to classify CWS appearance based on etiology.

A 1988 review of color fundus photographs analyzed CWS related to HIV retinopathy, diabetic retinopathy, hypertensive retinopathy, and central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO). HIV-related CWS were found to be smaller than those from other causes. CRVO showed a significantly greater total number of CWS, often in a ring configuration around the optic disc.

Another study comparing HIV-related and diabetic CWS used measurement criteria to identify differences. The main distinction was eccentricity: HIV retinopathy lesions had greater eccentricity (ratio of long to short axis) than diabetic lesions.

Grading Retinopathies Based on CWS

Cotton-wool spots play a role in grading systems for various retinopathies, particularly diabetic and hypertensive retinopathy.

Diabetic Retinopathy Grading: The ETDRS guidelines for diabetic retinopathy include soft exudates (CWS) in their grading paradigm. CWS are graded on a scale of 0 to 5, based on comparison with standard photographs, reflecting the severity and extent of CWS presence.

Hypertensive Retinopathy Grading: Hypertensive retinopathy has been graded since 1939 using the Keith-Wagener-Barker system.

- Grade 1 & 2: Arteriolar narrowing and arteriovenous nicking, typically seen in chronic hypertension.

- Grade 3: Includes CWS, hemorrhages, and intraretinal lipid exudates, associated with acute or severe chronic hypertension.

- Grade 4: Grade 3 findings plus optic disc blurring or macular star exudates, typically seen in acute or malignant hypertension.

A more recent system by Wong and Mitchell classifies hypertensive retinopathy into mild, moderate, and malignant categories.

- Mild Retinopathy: Arteriovenous nicking, arteriolar narrowing, or copper wiring.

- Moderate Retinopathy: Retinal hemorrhages, microaneurysms, CWS, or hard exudates.

- Malignant Retinopathy: Moderate retinopathy with optic disc swelling.

This newer system links retinopathy grades to systemic associations, with moderate and malignant retinopathy strongly associated with stroke, coronary artery disease, cognitive decline, and death. Even a single cotton wool spot in a hypertensive patient is a serious finding, indicating acute hypertension and increased risk of severe cardiovascular events.

Diagnostic Work-up

Finding a cotton-wool spot necessitates a systematic work-up. The initial step involves reviewing the patient’s medical and ocular history, medications, and symptoms related to common associated disorders. Key symptoms to inquire about include polyuria, polydipsia, weight changes, headaches, altered mental status, fever, joint pain, rashes, fatigue, and recent illnesses. Ophthalmic symptoms such as dry eye, history of uveitis, vision changes, and recent refractive changes are also important.

The extent of the work-up depends on other ocular findings and the patient’s history. If a known diagnosis associated with CWS is already present, further work-up might be tailored or less extensive.

Basic Diagnostic Evaluation for new CWS of unknown cause includes:

- Complete dilated eye examination

- Blood pressure measurement

- Fasting glucose and glucose tolerance test

- HIV antibody screen

- Basic chemistry panel

- Complete blood count

This basic evaluation can be initiated by an eye care provider but should involve communication with the patient’s primary care physician to coordinate care for any identified underlying systemic issue. The ophthalmologist should emphasize the systemic significance of CWS to the PCP.

A more extensive guided work-up may be needed if initial evaluations are inconclusive or if symptoms suggest less common etiologies. This can include:

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT)

- Lipid profile

- Anti-nuclear antibody test (ANA)

- Anti-phospholipid antibodies and Rheumatoid factor

- Carotid duplex ultrasound

- Anti-nuclear cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)

- CD4 count

- Echocardiogram

- Toxoplasmosis levels

- Homocysteine level

- Protein C and S levels and function

- Diagnostic imaging (as indicated by clinical suspicion)

Imaging Techniques for CWS

Various imaging techniques are used to study cotton-wool spots.

Fluorescein Angiography (FA): FA has been used for decades and typically shows CWS fluorescing brightly in the early phases after dye injection. The fluorescent area often appears larger than the clinically visible spot. FA can also detect fluorescent areas that precede visible CWS and persist after the visible spot resolves. Sometimes, a ring of microaneurysms surrounding a CWS can be observed in FA.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): OCT reveals thickening confined to the retinal nerve fiber layer at the location of CWS. Follow-up OCT scans show resolution of edema, typically followed by retinal thinning in the area of the resolved lesion, corresponding to nerve fiber layer loss.

Scanning Laser Polarimetry: Scanning laser polarimetry has been used to identify retinal nerve fiber layer defects following CWS. This can correlate with visual field defects in patients with CWS, suggesting nerve fiber layer damage as the cause of visual changes.

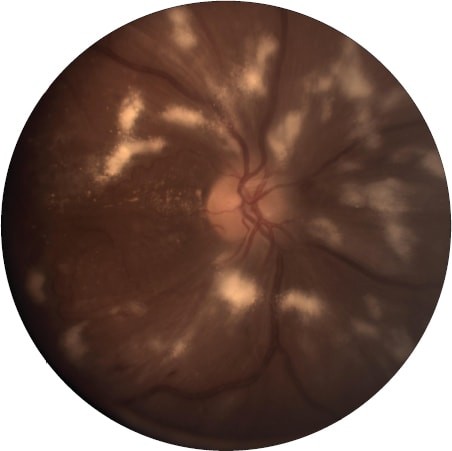

Fundus photograph of the right optic disc of a patient demonstrates multiple cotton-wool spots, retinal edema, a few intraretinal hemorrhages, and lipid exudates temporal to the disc. This patient suffered from radiation retinopathy.

Fundus photograph of the right optic disc of a patient demonstrates multiple cotton-wool spots, retinal edema, a few intraretinal hemorrhages, and lipid exudates temporal to the disc. This patient suffered from radiation retinopathy.

Prognosis and Time to Resolution

The resolution time for cotton-wool spots varies depending on the underlying cause. Understanding these timeframes is crucial for prognosis and management. Once the underlying condition is treated, CWS are expected to resolve.

CWS in HIV/AIDS tend to be smaller and have a shorter half-life (4 to 13 weeks, mean 6.9 weeks) compared to those in diabetes, hypertension, and CRVO. Hypertensive CWS also typically resolve within 6 to 12 weeks. In contrast, diabetic CWS have a significantly longer half-life, averaging 8.1 months in patients under 40 and 17.2 months in those over 40. This difference in resolution time likely reflects the extent of vascular damage, with diffuse capillary damage in diabetic retinopathy versus more localized arteriolar and capillary damage in HIV/AIDS and hypertensive retinopathy.

Significance and Conclusion

Cotton-wool spots themselves rarely cause significant visual impairment directly. However, their primary significance lies in their role as indicators of systemic pathologies, such as hypertension, diabetes, inflammatory conditions, and HIV, which can lead to serious ocular and systemic complications. CWS should be considered “cotton-wool sentinels,” signaling underlying systemic diseases that can cause organ damage.

Ophthalmologists play a crucial role in recognizing these signs and communicating their systemic implications to primary care physicians. By identifying CWS, ophthalmologists can contribute to the early detection and management of significant systemic conditions, potentially altering the disease trajectory for patients. The ‘cotton wool appearance’ is thus a critical diagnostic clue, both in ophthalmology and as an analogy for diagnostic processes in fields like automotive repair, where identifying seemingly minor signs can reveal major underlying problems.

References

- Duke-Elder WS. Textbook of Ophthalmology. Mosby; New York, NY; 1941:2715.

- Dollery CT. Microcirculatory changes and the Cotton-wool Spot. Proc Royal Soc Med. 1969;62:1267-1269.

- Grading diabetic retinopathy from stereoscopic color fundus photographs–an extension of the modified Airlie House classification. ETDRS report number 10. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:786-806.

- Wolter JR. Pathology of a Cotton-wool Spot. Am J Ophthalmol. 1959;48:473- 485.

- Harry J, Ashton N. The Pathology of Hypertensive Retinopathy. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1963;83:71-90.

- Murata M, Yoshimoto H. Morphological study of the pathogenesis of retinal cotton wool spot. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1983;27:362-379.

- Ashton N. Pathological and ultrastructural aspects of the cotton-wool spot. Proc Royal Soc Med. 1969;62:1271-1276.

- Dollery CT, Hodge JV, Engel M. Studies of the retinal circulation with fluorescein. BMJ. 1962;2:1210-1215.

- Shakib M, Ashton N. Ultrastructural changes in focal retinal ischemia. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1966;50:325-384.

- McLeod D. Clinical sign of obstructed axoplasmic transport. Lancet. 1975;2:954-956.

- Arroyo JG, Irvine AR. Retinal distortion and cotton-wool spots associated with epiretinal membrane contraction. Ophthalmology. 1995. 102:662-668.

- Brown GC, Brown MM, Hiller T, Fischer D, Benson WE, Magargal LE. Cottonwool spots. Retina. 1985;5:206-214.

- Mansour AM, Jampol LM, Logani S, Read J, Henderly D. Cotton-wool spots in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome compared with diabetes mellitus, systemic hypertension, and central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106:1074-1077.

- Jaworski C. Morphology of the HIV versus the diabetic cotton wool spot. Optom Vis Sci. 2000;77:600-604.

- Keith NM, Wagener HP, Barker NW. Some different types of essential hypertension: Their course and prognosis. Am J Med. Sci. 1939;197:332-343.

- Wong TY, Mitchell P. Hypertensive retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2310- 2317.

- Wong TY, Klein R, Couper DJ, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and incedent strokes: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Lancet. 2001;358:1134-1140.

- Wong TY, Klein R, Sharrett AR, et al. Cerebral white matter lesion, retinopathy and incident cerebral stroke. JAMA. 2002;288:67-74.

- Duncan BB, Wong TY, Tyroler HA, et al. Hypertensive retinopathy and incident coronary heart disease in high risk men. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1002- 1006.

- Wong TY, Klein R, Sharrett AR, et al. Retinal arteriolar narrowing and risk of coronary heart disease in men and women: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. JAMA. 2002;287:1153-1159.

- Wong TY, Klein R, Nieto FJ, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and 10 year cardiovascular mortality: a population-based case-control study. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:933-940.

- Wong, TY, Klein R, Sharrett AR, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities in cognitive impairment in middle aged persons: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Stroke. 2002;33:1487-1492.

- Zhang L, Liang X, Zhang J, et al. Cotton-wool spot and optical coherence tomography of a retinal nerve fiber layer defect. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:913.

- Ioannides A, Georgakarakos N, Elaroud I, Andreou P. Isolated cotton-wool spots of unknown etiology: management and sequential spectral domain optical coherence tomography documentation. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1431-1433.

- Alencar LM, Medeiros FA, Weinreb R. Progressive localized retinal nerve fiber layer loss following a retinal cotton wool spot. Semin Ophthalmology. 2007;22:103-104.

- Mansour AM, Rodenko G, Dutt R. Half-life of cotton-wool spots in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Int J STD AIDS. 1990;1:132-133.

Figure: Fundus photograph illustrating multiple cotton-wool spots, retinal edema, intraretinal hemorrhages, and lipid exudates in a patient with radiation retinopathy.