Background

Cough stands out as the most prevalent complaint prompting patients to seek consultation from their primary care physicians, accounting for approximately 8% of all visits. Given the significant advancements in medical understanding and the emergence of substantial new evidence, an updated and comprehensive guideline on cough from the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM) was deemed necessary. The previous version of these guidelines was released in 2008, making a revision crucial to incorporate the latest research and best practices in cough management.

Methods

This updated S3 guideline on cough, developed by DEGAM, is the result of an interdisciplinary effort based on both evidence and expert consensus. The update process involved a systematic review of pertinent literature published between 2003 and July 2012. Databases including MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and Web of Science were thoroughly searched. The evaluation of evidence levels and the implementation of consensus procedures adhered to the stringent standards set by the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF). This collaborative effort included the participation of seven medical societies to ensure a broad and robust perspective.

Results

The updated guideline is informed by 182 publications, which include a substantial body of high-level evidence: 45 systematic reviews (26 with meta-analyses) and 17 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Through a nominal group process, expert consensus was reached on 11 key recommendations specifically for managing acute cough. The cornerstone of diagnostic evaluation, as emphasized in the guideline, remains a thorough patient history and physical examination. Notably, for patients clinically diagnosed with acute, uncomplicated bronchitis, the guideline strongly advises against routine laboratory tests, sputum evaluations, or chest x-rays. Furthermore, it explicitly recommends against the use of antibiotics in these cases. The guideline also highlights the limited evidence supporting the effectiveness of antitussive or expectorant medications for acute cough, while acknowledging that the evidence base for phytotherapeutic agents is varied. For individuals diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia, the guideline recommends empirical antibiotic treatment for a duration of 5 to 7 days, with the specific choice of antibiotic influenced by individual risk factors. In the routine management of influenza, the guideline advises against routine laboratory testing and the use of neuraminidase inhibitors, except in specific circumstances.

Conclusion

A primary objective of these updated recommendations is to significantly reduce the inappropriate use of antibiotics in the treatment of common colds and acute bronchitis, conditions for which antibiotics are not indicated and offer minimal benefit. The guideline underscores the need for further clinical trials focusing on cough treatments to strengthen the currently fragmented evidence base and improve patient care.

Cough is the most frequent symptom leading patients to seek medical advice from primary care physicians, accounting for approximately 8% of all consultations (1). The prevalence of cough within the general population annually is estimated to be between 10% and 33% (2). The vast majority of acute cough cases are attributed to upper respiratory tract infections and acute bronchitis, collectively representing over 60% of diagnosed cases (1). The economic impact of cough is substantial. Respiratory tract infections contribute to around 20% of work absenteeism cases and approximately 10% of total sick leave days (3).

This article provides a concise overview of the key content and recommendations from the recently updated guideline on acute cough, defined as cough lasting less than 8 weeks. The guideline aims to clarify the differential diagnosis of cough in adult patients and to guide physicians in accurately identifying the underlying cause and delivering evidence-based treatment. It is specifically tailored for primary care practice, emphasizing practical relevance. Reflecting the realities of primary care settings, DEGAM guidelines are often symptom-focused rather than strictly diagnosis-oriented. This particular guideline adopts a similar approach, starting with the symptom of cough as the primary reason for consultation. Underlying diseases are discussed only insofar as they relate to cough, without delving into exhaustive detail on each condition.

Method

Revision of the Guideline

DEGAM established a comprehensive framework fifteen years ago for the development, dissemination, implementation, and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines (4). These guidelines are further supported by concise, practice-oriented summaries and patient-friendly information sheets. The original cough guideline was published in 2008. In 2013, a comprehensive update was undertaken, adhering to the rigorous standards for S3 guidelines under the supervision of the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF). This revision was driven by a significant accumulation of new evidence concerning both the diagnosis and treatment of cough.

Guideline Group

The guideline revision process involved representatives from seven German medical societies, ensuring a multi-faceted and expert-driven approach (Box 1). All members of the guideline group were required to disclose any potential conflicts of interest, a process thoroughly documented in the full guideline report to maintain transparency and integrity.

Box 1. Organizations and Individuals Involved in the S3 Guideline Revision

- Institute for General Practice, Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin

- Dr. Sabine Beck*1

- Prof. Vittoria Braun

- Dr. Lorena Dini MScIH*1

- Dr. Christoph Heintze MPH*1

- Dr. Felix Holzinger MPH*1

- Christiane Stöter MPH

- Dr. Susanne Pruskil MScPH

- Mehtap Hanenberg

- Max Hartog

- Representatives of Medical Societies

- Prof. Stefan Andreas, German Respiratory Society (DGP), German Society for Internal Medicine (DGIM)*1

- Patrick Heldmann MSc, Federal Association of Self-employed Physiotherapists (IFK)*1

- Dr. Susanne Herold PhD, German Society for Infectious Diseases (DGI)*1

- Dr. Peter Kardos, German Respiratory League

- Dorothea Pfeiffer-Kascha, German Association for Physiotherapy (ZVK)*1

- Dr. Guido Schmiemann MPH, German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM)*1

- Prof. Heinrich Worth, German Respiratory Society (DGP), German Respiratory League*1

- Guideline Patrons (DEGAM)

- Prof. Annette Becker

- Dr. Günther Egidi

- Dr. Detmar Jobst

- Dr. Guido Schmiemann MPH

- Dr. Hannelore Wächtler

- Acknowledgments

- Prof. Jost Langhorst

- Dr. Petra Klose

- Dr. Cathleen Muche-Borowski MPH (DEGAM, AWMF)

- Dr. Monika Nothacker MPH (AWMF)*2

- Dr. Anja Wollny MSc (DEGAM)

*1Participants of consensus conference

*2Moderator of consensus conference

Literature Review

The literature search strategy used for the original guideline was extended to include publications up to July 2012. The MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases were systematically searched. This was followed by a targeted search for relevant national and international guidelines and a manual search to identify sources published after the systematic database search concluded.

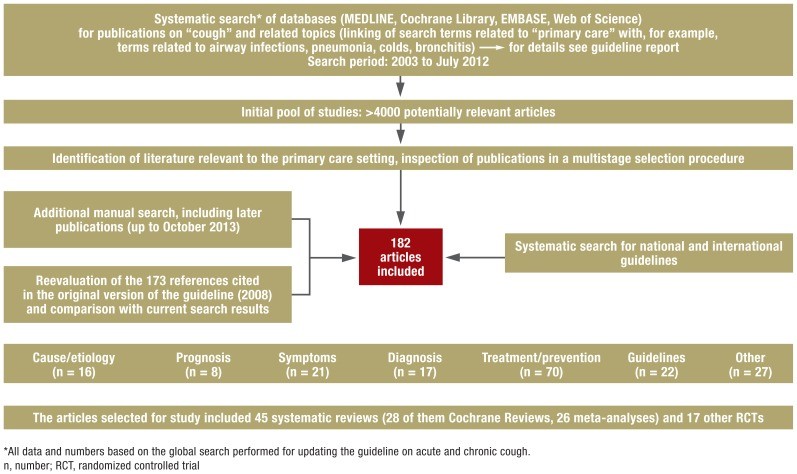

The identified sources underwent a rigorous inspection process, reviewing titles, abstracts, and full-text versions. Relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, and reviews (preferably systematic reviews) that met the inclusion criteria were selected, alongside high-quality clinical guidelines. In total, 182 publications were incorporated into the updated guideline, representing a comprehensive evidence base (Box 2, Figure).

Box 2. Examples of Search Terms Used

- Search terms related to acute cough (selection)

- (acute) cough*

- common cold*

- respiratory tract infections*

- bronchitis

- sputum

- pneumonia

- Search terms related to primary care (selection)

- general practice

- family practice*

- family medicine

- primary (health) care*

*Additional search in PubMed via corresponding MeSH terms; MeSH, medical subject headings

Figure 1. Literature Search Flow Chart

Overview of the literature search process.

Consensus Process

On June 17, 2013, a consensus conference, moderated by the AWMF, was convened to review the draft guideline. All recommendations, derived from the analysis of available evidence, were unanimously adopted through a nominal group process. The sole exception was one recommendation where a participant abstained due to a self-declared potential conflict of interest, ensuring the integrity of the consensus.

Strength of Recommendation

The strength of each recommendation is determined by both the robustness of the supporting evidence (study type, study design quality, internal validity, and potential for bias) and the criteria established by the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) Working Group (5). These GRADE criteria include factors such as the certainty regarding the magnitude of benefit from a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure, consideration of patient preferences, and cost-effectiveness. The guideline employs a three-tiered system to classify recommendation strength: A, B, and C (Table 1).

Table 1. Recommendations and Levels of Evidence for Acute Cough Management

| Recommendation Strength A | Evidence Level |

|---|---|

| Clinical diagnosis of acute uncomplicated bronchitis obviates the need for laboratory testing, sputum evaluation, and chest radiographs. | TIa, PII ↔ |

| Antibiotics should not be used to treat uncomplicated acute bronchitis. | TIa ↔ |

| Patients should be informed about the typical self-limiting course of acute (cold-related) cough. | TIb, SIII ↔ |

| Recommendation Strength B | Evidence Level |

| Technical investigations are generally unnecessary for acute cough in the absence of danger signs. | SIV ↑ |

| Expectorants (secretolytics, mucolytics) should generally not be used for acute cough associated with infection. | TIa ↓ |

| Antitussives should be used only in exceptional cases for acute cough associated with infection. | TIIa ↔ |

| Routine sputum evaluation is not necessary in community-acquired pneumonia. | DII, CII ↔ |

| In the absence of risk factors, empirical oral antibiotic treatment (aminopenicillin, or alternative tetracycline or macrolide) for 5 to 7 days is recommended for community-acquired pneumonia. | TIa ↓ |

| In the presence of risk factors, empirical oral antibiotic treatment (aminopenicillin with betalactamase inhibitor, or alternative cephalosporin) for 5 to 7 days is recommended for community-acquired pneumonia. | TIa ↓ |

| Routine laboratory testing (serology, direct virus detection) is not necessary when influenza infection is suspected. | TIa, DI ↓ |

| Neuraminidase inhibitors should be used only in exceptional circumstances for the treatment of seasonal influenza. | TIa ↓ |

Evidence Level Key: T=treatment-related; D=diagnosis-related; S=symptom-related; C=cause-related; P=prognosis-related.

Level I–IV: Strength of underlying evidence (treatment-related questions example): Ia=systematic reviews/meta-analyses; Ib=randomized controlled trials (RCTs); IIa=controlled cohort studies; IIb=case–control studies; III=non-controlled studies; IV=expert opinion/Good Clinical Practice, according to DEGAM guideline development concept (4).

Consensus Process/GRADE Criteria Application: ↔ Recommendation strength matches evidence level; ↑ Upgrading GRADE; ↓ Downgrading GRADE. GRADE=Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

Guideline Contents and Recommendations

History and Clinical Examination

In a significant proportion of patients presenting with acute cough in primary care settings, the diagnosis can be effectively established through a comprehensive medical history and symptom-oriented physical examination. In these instances, more advanced technical diagnostic investigations offer limited additional value (6).

The essential components of history taking and physical examination for patients with acute cough are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. History, Physical Examination, and Danger Signs in Acute Cough Evaluation

| History and Accompanying Symptoms |

|---|

| – Nature and duration of cough – Fever – Expectoration (amount, consistency, hemoptysis) – Breathing problems (dyspnea, stridor) – Smoking history – Previous respiratory tract infections, chronic bronchitis/sinusitis – Allergies, asthma, COPD |

| Physical Examination |

| – Skin inspection (pallor, cyanosis, sweating) – Mouth and throat inspection, nasal obstruction assessment, nasal sinus percussion for tenderness – Thoracic examination (inspection, percussion, and auscultation of lungs, respiratory rate, cardiac auscultation) – Abdominal palpation as indicated by history and clinical findings – Leg inspection and palpation (edema, signs of thrombosis) |

| Danger Signs (Red Flags) |

| Pulmonary embolism |

| Pulmonary edema |

| Status asthmaticus |

| Pneumothorax |

| Foreign body aspiration |

COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Danger Signs (Red Flags)

The primary goal of history taking and physical examination is to differentiate between benign infections and more serious conditions, enabling the early identification of patients at potential risk. In some cases, a life-threatening illness may be present or imminent (Table 2). Key warning signs, or “red flags,” include dyspnea, tachypnea, chest pain, hemoptysis, significant deterioration in general condition, and vital sign abnormalities (high fever, tachycardia, hypotension), particularly in the context of complicating underlying diseases (e.g., malignancy, immunodeficiency).

Immediate intervention is crucial in urgent cases. Typically, this involves prompt transport to a hospital accompanied by a physician or emergency medical personnel.

Frequent Diseases, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options

The most common differential diagnoses for acute cough are presented in Table 3. The subsequent sections discuss the most frequent causes of acute cough in more detail.

Table 3. Common Causes in Cough and Fever Differential Diagnosis

| Manifestation | Clinical Presentation |

|---|---|

| Acute Cough | – Colds (common cold, URTI) and acute bronchitis – Pneumonia – Influenza – Pertussis – Inhalation of irritants – Acute left heart failure with congestion |

| Acute and Chronic Cough | – COPD (including acute exacerbation) – Gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) – Upper airway cough syndrome (UACS) (formerly: postnasal drip syndrome) – Adverse drug effects |

COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; URTI = Upper Respiratory Tract Infection

Colds and Acute Bronchitis

Clinical Presentation: Upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs), commonly known as the “common cold,” are the most frequent cause of acute cough. Other typical symptoms include sore throat, nasal congestion and discharge, headache, muscle aches, fatigue, and sometimes fever. Viral infections are the primary culprits (adenoviruses, rhinoviruses, influenza and parainfluenza viruses, coronaviruses, respiratory syncytial virus [RSV], coxsackieviruses). Cough in acute bronchitis initially presents as dry, progressing to productive cough. The distinction between a cold and acute bronchitis (involving the lower respiratory tract) is not always clear-cut. Colds are typically self-limiting, resolving within 2 weeks in two-thirds of cases, whereas cough associated with bronchitis can persist for several weeks (7). Acute sinusitis, often occurring with a cold, can also trigger cough receptors.

Diagnosis: If the patient’s history and clinical findings are consistent with a cold or bronchitis, and if danger signs are absent (Table 2), neither chest radiography nor clinical chemistry tests are generally necessary. Differentiating between viral and bacterial bronchitis by measuring leukocyte count or C-reactive protein (CRP) is not clinically useful, as these findings do not alter treatment strategies (8). Sputum color is not a reliable indicator for diagnosing bacterial bronchitis or distinguishing between pneumonia and bronchitis (9, 10). Sputum examination in otherwise healthy patients with bronchitis is not indicated, as antibiotics are not routinely required (11). Spirometry may be considered if there are signs of bronchial obstruction, as acute bronchitis can induce temporary airway constriction (9). Persistent cough should be further investigated if it lasts beyond 8 weeks.

Treatment: Evidence supporting the efficacy of non-pharmacological treatments for colds and bronchitis is limited. Maintaining adequate hydration is physiologically sensible, but excessive fluid intake can potentially lead to hyponatremia (12). Smoking cessation is strongly advised, as both active and passive smoking prolong recovery from colds (13). The effectiveness of nasal saline rinses/sprays or steam inhalation is inconsistently supported by RCTs (14, 15). To minimize transmission, coughing into the elbow rather than the hand is recommended. Frequent hand washing, particularly during cold and flu seasons, is a sensible preventive measure (16).

Cough associated with a cold or acute bronchitis/sinusitis typically resolves without specific medicinal intervention. Patients should be reassured that these illnesses are usually self-limiting and benign, often negating the need for medication. However, symptomatic relief medications can be considered if desired by the patient.

Analgesics such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen are recommended for symptomatic management of headache and muscle aches. RCTs have not demonstrated a significant advantage of antitussives (e.g., codeine) over placebo in reducing cough frequency in the common cold. Nonetheless, antitussives may improve nighttime sleep quality (17, 18). Expectorants are frequently prescribed for productive cough, despite limited evidence of their effectiveness in acute cough. High-quality observational studies or RCTs supporting their use in this context are lacking (19. The applicability of findings from chronic bronchitis studies to acute bronchitis or colds remains uncertain. Decongestant nose drops or nasal sprays can provide short-term symptom relief, but prolonged use beyond 7 days offers no sustained benefit and may lead to rhinitis medicamentosa (20).

The evidence for phytotherapeutics is complex to interpret due to variations in study methodologies and the diverse compositions of plant-based preparations. Some RCTs have indicated positive effects of standardized myrtol on symptom severity and recovery time (21, 22. One study reported a 62.1% reduction in daytime coughing frequency on day 7 with myrtol, compared to 49.8% in the placebo group (22). Adverse effects are generally mild and primarily gastrointestinal. Another RCT showed slightly improved symptom relief with a thyme and ivy leaf preparation (77.6% reduction in cough attacks on day 9 versus 55.9% for placebo). Similar effects have been observed with thyme and primrose root combinations. Severe side effects are not commonly reported with these preparations (23, 24). A limited number of studies suggest a slight dose-dependent acceleration of recovery from bronchitis with Pelargonium sidoides (25, 26). However, placebo-controlled studies have reported a higher incidence of gastrointestinal adverse effects compared to placebo. It is important to note that definitive conclusions regarding the benefit-harm balance of Pelargonium sidoides are still pending due to reports of potential severe hepatotoxicity. A Cochrane Review suggested potential therapeutic efficacy of early administration of above-ground parts of Echinacea for colds (27). Oral intake carries a low risk of adverse effects such as allergies. Contraindications, such as tuberculosis, AIDS, and autoimmune diseases, must be considered. No preventive or therapeutic effect has been established for Echinacea root components.

Regular vitamin C intake has no significant impact on cold frequency in the general population, except for individuals under extreme physical stress (e.g., marathon runners) who may experience a reduced risk of colds (28). Vitamin C has not demonstrated therapeutic benefit when taken at the onset of a cold. A meta-analysis (29) indicated that regular zinc intake might reduce cold symptom duration; however, adverse effects including nausea and unpleasant taste have been reported. Routine zinc supplementation cannot be broadly recommended due to uncertainties regarding optimal dosage and duration of intake.

Antibiotic treatment is generally not necessary for uncomplicated acute bronchitis. Antibiotics provide minimal symptomatic relief and shorten recovery time by less than a day, while carrying risks of adverse effects and antibiotic resistance development (11). Patient education can effectively reduce antibiotic prescription rates (9, 30). Antibiotic administration may be considered in select patients with serious chronic conditions or immunodeficiencies, where ruling out pneumonia can be challenging (9). However, even in these populations, routine antibiotic prescription is discouraged, as bronchitis is typically viral in etiology.

Pneumonia

Clinical Presentation: Cough accompanied by tachypnea, tachycardia, high fever, characteristic lung auscultation findings, and pleuritic chest pain may indicate pneumonia. Pneumonia can present atypically, particularly in older, immunocompromised patients, or those with chronic lung disease, potentially without fever (31).

Diagnosis: Chest radiography in two views is advisable, especially when diagnostic uncertainty exists, in cases of severe illness, or in patients with comorbidities (31). Neither leukocyte count nor CRP levels definitively confirm pneumonia diagnosis (32). CRP measurement may be helpful in monitoring disease progression, but routine measurement is not recommended for outpatients. Procalcitonin measurement has shown potential to reduce antibiotic use, but routine procalcitonin testing is not currently recommended due to cost considerations (33, 34. Sputum tests in outpatients with community-acquired pneumonia have low sensitivity and specificity. Furthermore, targeted antibiotic treatment is not superior to empirical therapy (31, 34, making routine sputum testing generally unnecessary in community-acquired pneumonia.

Treatment: Clinically stable patients with community-acquired pneumonia can be managed in the primary care setting. Empirical antibiotic treatment choice depends on the presence of risk factors, which necessitates considering a broader spectrum of potential pathogens (31). Clinical reassessment of treatment effectiveness is needed within 48 to 72 hours. Extending treatment beyond 7 days does not improve success rates (35. Fluoroquinolones should be reserved for exceptional cases in the outpatient setting due to significant adverse effects and resistance development (Table 4).

Table 4. Antibiotic Treatment Guidelines for Community-Acquired Pneumonia*

| Patients Without Risk Factors |

|---|

| Substances |

| Penicillin (oral): Amoxicillin |

| Tetracycline (oral): Doxycycline |

| Macrolide (oral): Roxithromycin Clarithromycin |

| Azithromycin |

| Patients With Risk Factors (Antibiotic Use in Prior 3 Months, Severe Comorbidity, Nursing Home Resident) |

| Substances |

| Aminopenicillin + betalactamase inhibitor: e.g., sultamicillin (oral) |

| Alternative: cephalosporins: e.g., cefuroxime axetil (oral) |

*Modified from (31)

Influenza

Clinical Presentation: Influenza typically presents with abrupt onset of symptoms including high fever, marked malaise, and muscle pain.

Diagnosis: Influenza diagnosis is usually clinical. Antibody testing or direct viral detection via swabs should be reserved for cases of diagnostic uncertainty or when treatment decisions depend on confirmation (see below).

Treatment: Neuraminidase inhibitors can be considered if initiated within the first 48 hours of symptom onset. However, evidence of their efficacy is not definitive, and due to a limited cost-benefit ratio, these agents are recommended only for select patients (e.g., some immunocompromised individuals) (36). Given the potentially severe course of influenza, hospitalization should be considered, especially for elderly, multimorbid patients, and those with complications.

Vaccination against influenza is recommended for individuals over 60 years by the German Standing Committee on Vaccination Recommendations (STIKO). However, a recent meta-analysis using strict inclusion criteria suggests that vaccine efficacy may be suboptimal in some cases. Furthermore, RCT data for individuals over 65 are lacking (37).

Pertussis (Whooping Cough)

Clinical Presentation: Pertussis is increasingly recognized in adults, often presenting with an atypical, milder clinical course characterized by non-specific dry cough. Vaccine-induced immunity wanes after a few years. In the initial catarrhal stage, distinguishing pertussis from a common cold can be difficult. The characteristic paroxysmal whooping cough typically develops after 1 to 2 weeks (secondary peak) and can persist for 4 weeks or longer.

Diagnosis: Pathogen identification by culture of nasopharyngeal secretions is reliable only within the first 2 weeks of illness (38). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is more sensitive and can detect infection up to 4 weeks after onset, but is more expensive. In later stages of the disease, serology may confirm the diagnosis, with results interpreted in conjunction with clinical presentation and after consultation with the laboratory.

Treatment: In the catarrhal stage, recovery may be accelerated by treatment with azithromycin or clarithromycin. Antibiotic treatment remains beneficial later in the disease course as it reduces the period of contagiousness (39). Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for household contacts of children under 6 months of age. Vaccination according to STIKO recommendations is strongly encouraged. The pertussis vaccine is available only in combination vaccines.

Asthma and Infection-Exacerbated COPD

Chronic respiratory diseases can present with acute exacerbations or initially manifest with cough symptoms. National Disease Management Guidelines should be consulted for detailed guidance on the diagnosis and management of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Implementation and Outlook

For uncomplicated colds and acute bronchitis, the central guideline recommendation emphasizes diagnostic and therapeutic restraint. It is crucial to educate patients with these benign, self-limiting conditions that extensive technical investigations and medicinal treatments are generally unnecessary. The guideline, along with associated patient information sheets, provides evidence-based arguments to support primary care physicians in addressing patient anxieties and questions regarding treatment options. Even in cases of bronchitis with yellow-green sputum or mild fever, patients can be reassured that the infection is most likely viral, and antibiotic treatment is not indicated. In clinical practice, antibiotics are frequently prescribed for URTI or bronchitis, contributing to antibiotic resistance (10, 40). If patients strongly request treatment, general symptom-relieving agents, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or decongestant nose drops, can be recommended. Phytotherapeutic options, some of which have demonstrated modest symptom relief or shortening of illness duration, may also be considered. However, patients should be informed of the costs and potential, albeit usually minor, adverse effects. Shared decision-making between physician and patient is essential when considering such preparations. Furthermore, given the widespread use of cough treatments lacking robust evidence of benefit, methodologically sound, publicly funded research is needed to systematically evaluate these substance groups specifically for the indication of “acute cough.”

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

[1] Eccles R, Weber O. Common cold. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;30:587–96. [PubMed]

[2] Morice AH, McGarvey L, Pavord I, British Thoracic Society Cough Guideline Group. British Thoracic Society cough guideline 2006. Thorax. 2006;61 Suppl 1:i1–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[3] Robert Koch Institut. Ergebnisse der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1-BEV) Berlin: RKI; 2013. [cited 2014 May 14]. Available from: http://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Gesundheitsmonitoring/Studien/Degs/degs1_bevs/degs1_bevs_node.html.

[4] Schäfer T, Kunz R, Ollenschläger G, Raspe H, Mühlhauser I, Gerlach FM. Methods for guideline development. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107:777–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[5] Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[6] Llor C, Bjerrum L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2011;2:41–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[7] Worrall GJ. Acute cough in general practice. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:1153–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[8] Gonzales R, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, Hickner JM, Hoffman JR, Sande MA, et al. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for treatment of uncomplicated acute bronchitis: background. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:521–9. [PubMed]

[9] Welschen AE,шиттеn M, мееuwsen EL, Dinant GJ. Do C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate discriminate between acute bronchitis and pneumonia? Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:623–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[10] thôi TG, van Driel ML, Broekhuijsen-van Dijk MP, Kolnaar BG, Rovers MM, Schilder AG, et al. Antibiotics for acute bronchitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD004108. [PubMed]

[11] van Vugt SF, Broekhuijsen-van Dijk MP, Ummels I, Spies TH, Verheij TJ, Bindels PJ, et al. Antibiotics for acute cough in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD004370. [PubMed]

[12] Farley TA. Hyponatremia in children with pneumonia. South Med J. 1986;79:1017–20. [PubMed]

[13] Almirall J, Morato P, Riera M, Balanzo X, Bolibar I. Community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a prospective study of etiology, clinical characteristics and outcome. Spanish CAP Study Group. Respir Med. 1999;93:439–45. [PubMed]

[14] Saks