Introduction

CREST syndrome is a recognized clinical condition linked to systemic sclerosis (SSc), characterized by the presence of at least three out of five key clinical features: calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia. While Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly, and esophageal dysmotility are commonly observed in classical SSc subsets, both limited and diffuse, their combined presence does not solely define CREST syndrome. Calcinosis, however, appears to be less frequent in SSc, and its association with other clinical features is a hallmark of CREST syndrome. This highlights calcinosis as a critical component in the diagnosis of CREST syndrome.

Methods

This study involved 37 individuals diagnosed with SSc, based on the 2013 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) criteria.

Results and Discussions

The study found that calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and esophageal dysmotility were present in both limited and diffuse SSc subsets, notably in the diffuse SSc subset, which contrasts with existing literature.

Conclusion

CREST syndrome is a distinct clinical entity that can overlap with both limited and diffuse SSc subsets. Given the varied perspectives on classifying CREST syndrome, further research is needed to refine the classification of SSc.

Keywords: systemic sclerosis, dystrophic calcinosis, CREST syndrome, telangiectasia, Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly

Introduction

CREST syndrome, as defined by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) 2013 criteria, is considered a subtype of systemic sclerosis (SSc). Diagnosis requires the presence of at least three of the following five clinical manifestations: calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia.1–5 Estimates from Valenzuela suggest that CREST syndrome affects over a quarter of individuals with SSc. It is typically associated with a prolonged disease course and the presence of anticentromere antibodies, which are known to be specific to the limited SSc subtype.6–8 Meyer’s research indicates that over half of CREST syndrome patients exhibit elevated anticentromere antibody levels.9 CREST syndrome has also been linked to positive anti-PM/Scl-70 antibody titers.6 While often following a benign course, CREST syndrome can, in rare instances, lead to complications such as pulmonary hypertension after more than a decade or gangrene, potentially requiring finger amputation.9

The acronym CREST was coined by Winterbauer in 1964 to describe this syndrome, encompassing its five cardinal features: Calcinosis (dystrophic calcification in subcutaneous tissue), Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, and Telangiectasias.6,10 CREST syndrome is also known as acrosclerosis or Thibierge-Weissenbach syndrome, named after the French physicians Thibierge and Weissenbach, who provided the initial case report in 1910.6,9 The exact cause of CREST syndrome remains unknown, but research suggests the involvement of local factors such as chronic inflammation, repeated trauma, capillary deoxygenation, and bone matrix damage. It is also associated with acroosteolysis and digital ulceration. Studies indicate that over half of CREST syndrome cases present with elevated anticentromere antibodies.6 Ohira and colleagues have noted that CREST syndrome is frequently incomplete, with Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia being the most commonly associated clinical features, while calcinosis and esophageal dysmotility are less frequently observed.11

Afifi et al. identified coronary calcifications in SSc patients without cardiac symptoms using multidetection computed tomography to assess coronary and extracoronary calcium index. Their findings revealed higher scores in patients with limited SSc compared to those with diffuse SSc, suggesting a cardiovascular risk in SSc patients due to coronary atheroma plaque calcification.12 Atherosclerosis is understood as an inflammatory process involving monocytes, macrophages, T lymphocytes, cytokines, and autoantibodies. Autoimmune diseases, characterized by chronic inflammation, inherently carry a cardiovascular risk.13

A Japanese study by Takahashi et al. highlighted the potential association of CREST syndrome with other autoimmune conditions. They reported a case of a 64-year-old patient with multiple immunopathies including recurrent myelitis with high anti-aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibody titers, primary biliary cirrhosis, Sjogren’s syndrome, and CREST syndrome.14 The presence of one autoimmune disease may predispose individuals to developing additional immunopathies, reflecting a broader disruption of the immune system, as supported by other studies.15–17 Autoimmune fibrosis is a shared mechanism between primary biliary cirrhosis and SSc with high anticentromere antibodies, as reported by several authors.18,19 Fibrosis arises from increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL6, IL1, IL17, TNFα) released by inflammatory cells, which have pro-fibrotic effects.11,20–22 This fibrosis manifests as skin thickening, measurable by the modified Rodnan skin score, and can be assessed using ultrasound elastography and high-frequency ultrasound, revealing skin involvement and potential calcifications in SSc patients.23,24

Materials and Methods

We conducted a study involving 37 patients with SSc, diagnosed according to the 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria.5,25 These patients were from southeastern Romania and were hospitalized in a university clinic in Bucharest, Romania. The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Clinical Hospital “St. Maria” in Bucharest (No. 5213, dated 04.04.2019), and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence of clinical features associated with CREST syndrome in a group of SSc patients, encompassing both limited and diffuse subtypes. Specifically, we aimed to emphasize the presence of Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, and sclerodactyly in both disease subtypes, and to determine if the less common features of telangiectasia and calcinosis could indicate the presence of CREST syndrome in SSc patients. The patient group consisted predominantly of women (30 women and 7 men, representing 81.1% and 18.9% respectively). Approximately one-third of the patients (13) were from rural areas, while 24 were from urban areas. Patient ages ranged from 28 to 76 years.

Patient selection was based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: a confirmed diagnosis of SSc according to the revised 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria, known for their high sensitivity (Table 1). Cases of scleroderma “sine scleroderma” were considered but not found, and dermal sclerosis was assessed using LeRoy criteria to categorize patients into limited or diffuse subtypes. The duration between the onset of the first symptom and the development of dermal sclerosis was recorded. Additionally, comorbidities, toxic exposures, and stressful life events were analyzed alongside the SSc diagnosis.

Table 1.

The New ACR/EULAR Classification Criteria from 2013 for SSc Diagnosis

| Diagnostic Criteria | Score |

|---|---|

| Skin sclerosis/thickening of the fingers proximal to the metacarpophalangeal joints | 9 |

| Sclerodactyly or digital edema | 4/3 |

| Fingertip pulp ulcers or stellate scars | 2/3 |

| Telangiectasia | 2 |

| Abnormal capillaries | 2 |

| Lung fibrosis | 2 |

| Lung arterial hypertension | 2 |

| SSc specific antinuclear antibodies – anti-centromere – anti-Scl-70 – anti-RNA polymerase III | 3 |

| Raynaud’s phenomena | 2 |

Note: Data from Masi AT, Medsger TA Jr.25

Data from the study were entered into an Excel file and analyzed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp.). Statistical analysis included descriptive statistics for quantitative data, and frequency distributions and contingency tables for qualitative data. The Chi-squared test was used for sample comparisons, with all p-values being two-tailed, and a p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and Discussions

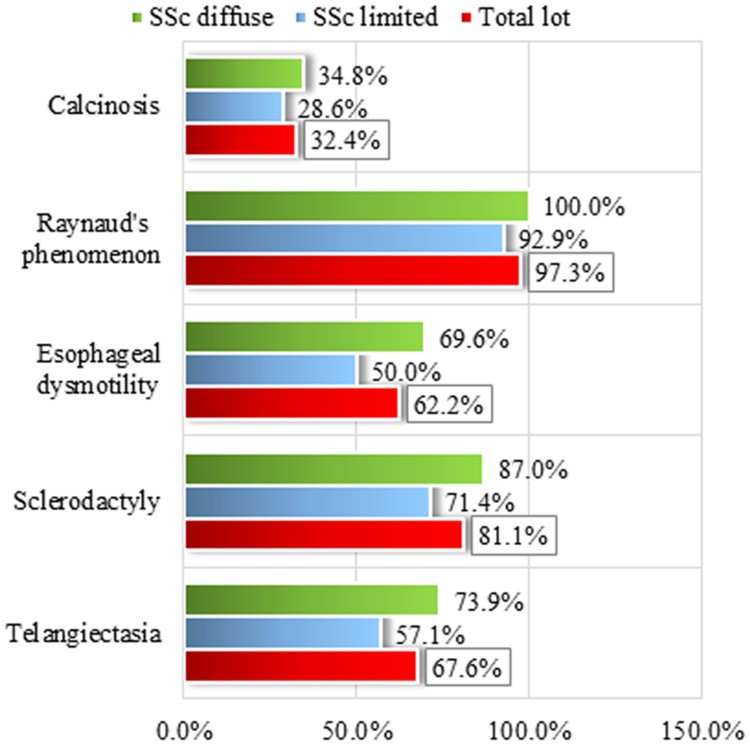

Raynaud’s phenomenon was the most frequently observed clinical feature of CREST syndrome in our study group (Figure 1). It was present in nearly all SSc patients (diagnosed by ACR/EULAR criteria, as detailed in Table 2), with only one exception in a patient with diffuse SSc.

Figure 1.

Clinical elements of CREST syndrome: Frequency distributions for the total group and by subsets of SSc. Alt Text: Bar chart showing frequency distribution of CREST syndrome clinical elements (Calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysfunction, Sclerodactyly, Telangiectasia) in Limited SSc, Diffuse SSc, and Total SSc groups.

Table 2.

Frequency Distribution by SSc ACR Criteria, in Both Subgroups and Total Group of Patients

| SSc ACR Criteria | Limited SSc | Diffuse SSc | Total | Chi-Square | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % |

| 1 major criterion | No | ||||

| Yes | 14 | 100.0% | 23 | 100.0% | 37 |

| 2 minor criteria | No | 8 | 57.1% | 4 | 17.4% |

| Yes | 6 | 42.9% | 19 | 82.6% | 25 |

| Total | 14 | 100.0% | 23 | 100.0% | 37 |

Note: Bold value indicates statistically significant. Alt Text: Table showing frequency distribution of SSc ACR criteria (1 major, 2 minor) in Limited SSc, Diffuse SSc, and Total SSc groups, with Chi-Square and p-values.

Following Raynaud’s phenomenon in frequency (Table 3), sclerodactyly was observed in most patients (81.1%), with a higher prevalence in the diffuse SSc subset (87.0%). Telangiectasia and esophageal dysmotility showed similar frequencies (Figure 1), present in approximately two-thirds of the total patient group. Again, the diffuse SSc subset exhibited higher percentages for both telangiectasia and esophageal dysmotility (73.9% and 69.9%, respectively). Calcinosis was the least common of the five CREST syndrome features, identified in only about one-third of the entire group (32.4%). The distribution of calcinosis across SSc subsets was similar to that of sclerodactyly, with a slightly higher presence in the diffuse SSc subset (34.8%) compared to the limited SSc subset (28.6%).

Table 3.

CREST Syndrome Elements – Patient Group and Disease Subgroups Frequency Distribution

| CREST Syndrome Elements | Limited SSc | Diffuse SSc | Total | Chi-Square | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Calcinosis | No | 10 | 71.4 | 15 | 65.2 |

| Yes | 4 | 28.6 | 8 | 34.8 | 12 |

| Raynaud phenomena | No | 1 | 7.1 | 1 | 2.7 |

| Yes | 13 | 92.9 | 23 | 100.0 | 36 |

| Esophageal dysfunction | No | 7 | 50.0 | 7 | 30.4 |

| Yes | 7 | 50.0 | 16 | 69.6 | 23 |

| Sclerodactyly | No | 4 | 28.6 | 3 | 13.0 |

| Yes | 10 | 71.4 | 20 | 87.0 | 30 |

| Telagiectasia | No | 6 | 42.9 | 6 | 26.1 |

| Yes | 8 | 57.1 | 17 | 73.9 | 25 |

| Total | 14 | 100.0% | 23 | 100.0% | 37 |

Abbreviations: NS, not statistically significant; SS, statistically significant. Alt Text: Table showing frequency distribution of CREST syndrome elements (Calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomena, Esophageal dysfunction, Sclerodactyly, Telangiectasia) in Limited SSc, Diffuse SSc, and Total SSc groups, with Chi-Square and p-values.

Notably, our study found calcinosis more frequently in diffuse SSc patients, which is not typically associated with this subset.26 Jacobsen et al. have observed that SSc forms with high anticentromere antibody titers are associated with calcinosis, digital ulceration, and telangiectasia.26 Anticentromere antibodies are known to be specific to limited SSc and are linked to a better prognosis compared to diffuse forms.7,27

Considering the views of researchers who classify CREST syndrome as equivalent to or a subtype of limited SSc, our findings do not support this equivalence. We observed calcinosis in both SSc subsets, particularly in diffuse SSc. Similarly, if CREST syndrome is considered a distinct SSc form, different from limited and diffuse SSc,10 our study also does not align with this, as CREST syndrome elements were present in both SSc subsets. Our results indicate that CREST syndrome is a clinical entity that can overlap with both limited and diffuse SSc. Consistent with this, Johnson noted the potential presence of CREST syndrome in most cases of limited and diffuse SSc,28 and Steen suggested in 2008 that CREST syndrome might represent a milder form with improved survival rates.29

Four of the five CREST syndrome clinical features—sclerodactyly, esophageal dysmotility, telangiectasia, and especially Raynaud’s phenomenon—were highly prevalent in both diffuse and limited SSc patients in our study. Calcinosis was the differentiating factor due to its lower prevalence. Given that Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia are components of the clinical presentation of both diffuse and limited SSc and often occur together regardless of the subset,4,5 we posit that CREST syndrome is defined by the combination of at least three of these five clinical elements, with calcinosis being an essential and mandatory feature. Therefore, we propose that calcinosis is the defining clinical element of CREST syndrome.

Calcinosis in CREST syndrome manifests as subcutaneous calcifications, developing due to local ischemia and tissue degeneration in SSc. Dystrophic calcinosis is a type of calcification characteristic of connective tissue diseases. Devitalized tissues in SSc are susceptible to calcium deposition even with normal plasma calcium and phosphate levels. SSc vasculopathy leads to local tissue hypoxia, damaging collagen and elastin fibers. Local inflammation further promotes calcification of these devitalized tissues. This ectopic mineralization primarily occurs in peri-articular subcutaneous tissue. The insoluble calcium deposits, composed of amorphous calcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite crystals, appear as agglomerations of inorganic crystalline materials, either localized or widespread. A granulomatous inflammatory reaction surrounds these deposits, leading to foreign body granuloma formation and fibrosis.1 These deposits, formed in an inflammatory environment, perpetuate recurrent inflammation, creating a vicious cycle. Furthermore, dystrophic calcinosis increases the risk of skin ulcers, which can become infected, and over time may cause joint contractures and muscle atrophy.6 Simultaneously, local ischemia reduces subcutaneous fat tissue.1

Calcinosis is a significant source of pain and disability. It can be diagnosed clinically or radiologically, but drug treatment is often ineffective.6 First-line treatments like colchicine and calcium channel blockers for subcutaneous calcification in SSc have not shown consistent efficacy.30 Similarly, bisphosphonates, thalidomide, and sodium thiosulfate have yielded discouraging results, and rituximab treatment has produced mixed outcomes.31 A 2019 study by Gordon et al. involving children with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria, who develop hydroxyapatite crystal calcifications, found zoledronic acid, pravastatin, and lonafarnib to be ineffective.32 Consequently, surgical excision of calcium deposits remains the primary treatment approach.6 However, some studies suggest that statins may be beneficial due to their anticalcification, anti-inflammatory, antithrombotic, and antioxidant properties.33,34 A study using mice models of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), a genetic disorder characterized by ectopic mineralization in arterial walls, reported positive results with atorvastatin administration, indicating statins can prevent abnormal mineralization but do not resolve existing deposits.35 Persistent skin ulcers associated with calcinosis or in acral regions require careful management to prevent infection, often necessitating combined topical treatments.36 Interestingly, Draganescu et al. highlighted the increased risk of skin lesions in HIV patients, suggesting that the inflammatory and immune status in HIV, even under antiviral therapy, may predispose to subcutaneous calcification.37

Since 1964, Winterbauer has classified CREST syndrome as a distinct SSc form with a more favorable prognosis.10,28 In 2001, the classification shifted, viewing CREST syndrome as a specific subtype of limited SSc. Johnson finds Le Roy’s classification into limited and diffuse SSc subsets practical and predictive, also noting that most cases of both subsets exhibit clinical features of CREST syndrome.28,38 More recently, Adiguin proposed that CREST syndrome is identical to limited SSc.39 Due to these divergent views on CREST syndrome classification, several authors advocate for a revised SSc classification system.6,28,39

We believe that microcalcifications (small calcium deposits) in SSc are more common than clinically, ultrasonographically, or radiologically detected, as there is a subclinical phase where they are undetectable by standard clinical examination. Nishikawa et al. successfully identified calcifications at the titanium piece-bone mass interface using laser scanning confocal microscopy.40 This suggests that early-stage calcium micro-deposits in the devitalized subcutaneous tissue of SSc could potentially be identified using more sensitive methods like laser scanning confocal microscopy or coherent optical tomography, long before they become clinically apparent. Future research should explore these advanced detection methods for earlier diagnosis.

Conclusion

Calcinosis was observed in both diffuse and limited SSc, indicating it is not exclusive to limited SSc or a specific SSc form, but rather a clinical entity that can overlay both SSc subsets.

Given that Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly, and esophageal dysmotility are frequently present in SSc and are insufficient on their own to define CREST syndrome, we argue that dystrophic calcinosis is the key diagnostic element. We emphasize that the term CREST syndrome should not be applied in the absence of calcinosis, contrary to some existing literature. The concept of CREST syndrome without calcinosis warrants a re-evaluation of terminology.

We also propose that dystrophic calcinosis in SSc is likely more prevalent than current statistics suggest, as early stages of calcium accumulation may only become detectable once deposits reach a size that allows for clinical identification.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the academic support from the ‘Dunarea de Jos’ University of Galati, Romania, through the Multidisciplinary Integrated Center of Dermatological Interface Research MIC-DIR.

Funding Statement

The article publishing charge was supported by the “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati, Romania.

Abbreviations

SSc, systemic sclerosis; CO, carbon monoxide, NO2, nitrogen dioxide, SO2, sulfur dioxide; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C reactive protein; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; ACA, anticentromere antibodies; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism.

Data Sharing Statement

Data access is available upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clinical Hospital “St. Maria” Bucharest (No. 5213, 04.04.2019) and complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for Publication

All patients provided informed consent for data and/or photograph publication, as part of their medical records.

Author Contributions

CB, EN, MC, and ALT contributed to study conception, manuscript writing, and revision. CB, ELP, CLM, CD, IC, LN, MD, VS, IAS, AN, AMP, GB, SC, and CIV were involved in data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1] Smith CJ, Denton CP. Calcinosis in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011 Jan;23(1):131-5.

[2] Mahler M, Fritzler MJ. Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma): from understanding the pathogenesis to novel and emerging therapies. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012 Mar;8(2):157-70.

[3] Allanore Y. Systemic sclerosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2011 Nov-Dec;21(6):807-17.

[4] LeRoy EC, Medsger TA Jr. Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). In: Koopman WJ, editor. Arthritis and Allied Conditions. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1997. pp. 1487–1517.

[5] van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Nov;65(11):2737-47.

[6] Gillanders S, Walker J, Rajaratnam R, Struthers G. Calcinosis in systemic sclerosis: current understanding and future directions. J Scleroderma Relat Disord. 2016 Sep-Dec;1(2):103-112.

[7] Stochmal A, Czuwara J, Trojanowska M, Rudnicka L. Anticentromere antibodies: клеточка by клеточка. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012 Apr;42(2):239-49.

[8] Sato S, Kuwana M. Clinical significance of anti-centromere antibody in systemic sclerosis. J Dermatol. 2011 Dec;38(12):1101-9.

[9] Meyer O. CREST syndrome. Rev Prat. 2001 Nov 15;51(20):2217-22.

[10] Winterbauer RH. Multiple telangiectasia, Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly, and subcutaneous calcinosis: a syndrome mimicking hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1964 Jul;114:361-83.

[11] Ohira T, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Clinical and serological features of systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma: a single center study in Japan. J Dermatol. 2007 Apr;34(4):233-8.

[12] Afifi L, Draijer W, van Roon AM, Smit JW, Reinders ME, Twisk JW, et al. Coronary artery calcifications in patients with systemic sclerosis are associated with disease subtype and not with traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Dec;71(12):1929-34.

[13] Libby P, Theroux P. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005 May 10;111(25):3481-8.

[14] Takahashi T, Kondo M, Suzuki J, Murashima R, Nakajima H, Takeuchi T, et al. CREST syndrome associated with recurrent myelitis with anti-aquaporin-4 antibody, primary biliary cirrhosis and Sjogren’s syndrome. Intern Med. 2013;52(11):1299-303.

[15] Luchetti MM, Tinazzi I, Seidel M, Adami S, Giollo A, Platzgummer S, et al. Clinical and immunological characterization of systemic sclerosis patients with multiple autoantibodies. Autoimmun Rev. 2011 Nov;11(1):69-72.

[16] Ghirardello A, Doria A, Ruffatti A, Cozzi F, Todesco S. Autoantibody profiles in patients with systemic sclerosis: clinical associations and disease evolution. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1993 Dec;23(3):155-63.

[17] Wiik AS. Autoantibodies in systemic rheumatic diseases. In: Rose NR, Mackay IR, editors. The Autoimmune Diseases. 3rd ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 127–210.

[18] Floreani A, Gershwin ME. Primary biliary cirrhosis and systemic sclerosis: distinct autoimmune diseases with shared features. Semin Liver Dis. 2011 Aug;31(3):308-15.

[19] Artigues E, Taieb J, Cazes A, Denjean R, Farge D, Wechsler B, et al. Systemic sclerosis associated with primary biliary cirrhosis: a report of 8 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999 Dec;141(6):1078-82.

[20] Sakkas LI, Platsoucas CD. The role of T cells in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007 Apr;148(1):21-30.

[21] Sgonc R, Gruber J. Interleukin-6 in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013 Oct;52(10):1767-78.

[22] Chizzolini C, Raschi E, Rezzonico R, Fazekasova H, Tyndall A. Cytokines and growth factors in systemic sclerosis: friends or foes? Autoimmunity. 2011 May;44(3):161-74.

[23] Cutolo M, Montagna P, Vremes-Kruc J, Sulli A, Sekelj F, Martinovic D, et al. High-frequency ultrasound and elastosonography assessment of skin involvement in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011 Dec;50(12):2268-76.

[24] Higashi-Kuwata N, Jinnin M, Makino K, Kajihara I, Fukushima S, Inoue Y, et al. Quantitative assessment of skin fibrosis in patients with systemic sclerosis by ultrasound elastography. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 May;63(5):1321-8.

[25] Masi AT, Medsger TA Jr. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980 Nov;23(5):581-90.

[26] Jacobsen G, Wildt M, Baslund B, Ryder LP, Garred P, Petersen J, et al. Clinical and immunological features in 86 Danish patients with systemic sclerosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1997 Jan;36(1):25-32.

[27] Lee P, Langevitz P,глобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулинглобулин