Pancreatitis, an inflammation of the pancreas, is a serious condition that can significantly impact overall health due to the pancreas’ crucial role in digestion and hormone regulation. For automotive experts who understand complex systems, think of the pancreas as the engine control unit (ECU) of the digestive system – when it malfunctions, the whole system suffers. Accurate and timely diagnosis is paramount for effective treatment and preventing severe complications. This article will delve into the essential Criteria For Diagnosis Of Pancreatitis, providing a detailed overview optimized for clarity and understanding.

Understanding Acute Pancreatitis Diagnosis

Diagnosing acute pancreatitis (AP) requires a careful evaluation based on a combination of clinical signs, laboratory tests, and imaging findings. Just like diagnosing a car problem isn’t based on a single indicator but a combination of symptoms, sensor readings, and visual inspections, pancreatitis diagnosis is multifaceted. According to established medical guidelines, a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is generally made when at least two of the following three criteria are met:

- Abdominal Pain: This is typically the most prominent symptom, often described as severe, persistent pain in the upper abdomen (epigastric region). Patients often report it radiating to the back. Think of it as a persistent engine warning light that doesn’t go away, signaling a serious internal issue.

- Elevated Pancreatic Enzymes: Blood tests revealing a significant increase in serum lipase or amylase levels – at least three times higher than the upper limit of normal – are a key diagnostic criterion. Lipase is generally considered more specific for pancreatic issues. These enzymes are like diagnostic trouble codes (DTCs) in a car; elevated levels strongly suggest pancreatic damage.

- Characteristic Imaging Findings: Imaging studies such as ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing features consistent with acute pancreatitis. These imaging techniques are analogous to using diagnostic tools like OBD-II scanners or endoscopes to visually inspect internal components for damage.

These three criteria form the cornerstone of acute pancreatitis diagnosis. Let’s explore each of these in more detail.

1. Abdominal Pain: The Primary Symptom

Abdominal pain in pancreatitis is not just a stomach ache; it’s a distinct type of pain. It’s often:

- Severe and Persistent: Unlike transient stomach cramps, pancreatitis pain is intense and lasts for hours or even days.

- Epigastric: Located primarily in the upper central abdomen, below the chest bone.

- Radiating to the Back: A characteristic feature where the pain extends or “wraps around” to the back.

- Sudden Onset: The pain typically starts abruptly.

However, it’s crucial to remember that abdominal pain alone isn’t enough for a diagnosis. Many conditions can cause abdominal pain. Therefore, while it’s a critical indicator, it must be corroborated with other diagnostic criteria.

2. Elevated Pancreatic Enzymes: Laboratory Confirmation

The pancreas produces enzymes like lipase and amylase, essential for digesting fats and carbohydrates. In pancreatitis, these enzymes leak out of the damaged pancreas and into the bloodstream, leading to elevated serum levels.

- Serum Lipase: Generally considered more specific and sensitive for acute pancreatitis than amylase. Lipase levels tend to remain elevated for a longer period (up to two weeks) compared to amylase.

- Serum Amylase: While less specific (as amylase can also be elevated in other conditions like salivary gland issues), it’s still a valuable marker. Amylase levels usually rise within 6-24 hours and return to normal within 5-7 days.

For diagnostic purposes, a level at least three times the upper limit of normal for either lipase or amylase is considered significant. It’s like seeing a critical sensor reading far outside the acceptable range, strongly suggesting a problem.

It’s important to note that while elevated enzymes confirm pancreatic injury, they don’t necessarily indicate the severity of pancreatitis or predict the disease’s course. Further assessment is needed for that.

3. Imaging Findings: Visualizing the Pancreas

Radiological imaging plays an increasingly vital role in diagnosing pancreatitis and assessing its complications. Different imaging modalities offer unique advantages:

3.1. Ultrasonography (US)

- First-line Imaging: US is often the initial imaging test due to its accessibility, low cost, and lack of radiation. It’s like a quick visual inspection without invasive procedures.

- Gallstone Detection: Excellent for detecting gallstones, a leading cause of pancreatitis. US has high sensitivity and specificity for gallbladder stones.

- Limitations: Image quality can be affected by bowel gas, which is common in pancreatitis. US may also have limited visualization of the pancreas itself, especially in obese patients.

Despite limitations in visualizing the pancreas directly, US is crucial for quickly identifying gallstones as a potential cause.

3.2. Computed Tomography (CT)

- Detailed Pancreatic Imaging: CT scans provide detailed cross-sectional images of the pancreas and surrounding tissues. Think of it as a high-resolution 3D scan of the engine.

- Assessing Complications: CT is excellent for identifying local complications like fluid collections, necrosis (tissue death), and pseudocysts.

- Severity Assessment: CT severity indices (CTSI) are used to grade the severity of pancreatitis based on CT findings.

- Limitations: Involves radiation exposure. CT may not be as sensitive in the very early stages of mild pancreatitis.

CT scans are typically reserved for cases where the diagnosis is uncertain after US, or when assessing the severity and complications of known pancreatitis. CT is particularly useful in distinguishing between interstitial edematous pancreatitis and necrotizing pancreatitis.

Figure 1.

Figure 1: Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) image showing acute pancreatitis with an enlarged, hypoechoic pancreatic head (PH), indicating inflammation.

3.3. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

- Superior Soft Tissue Contrast: MRI offers excellent visualization of soft tissues, including the pancreas and bile ducts, without radiation. It’s like having advanced imaging that highlights subtle tissue changes.

- Necrosis and Fluid Collection Assessment: MRI is highly sensitive for detecting pancreatic necrosis, fluid collections, and ductal abnormalities.

- MRCP for Bile Ducts: MRCP is a specific MRI technique focused on imaging the bile and pancreatic ducts, useful for identifying bile duct stones or obstructions.

- Limitations: More expensive and less readily available than US or CT. MRI scans take longer.

MRI, especially with MRCP, is often used as a problem-solving tool when US and CT findings are inconclusive, or when detailed ductal imaging is needed. It’s particularly valuable in patients where radiation exposure should be minimized, and for those with contraindications to CT contrast.

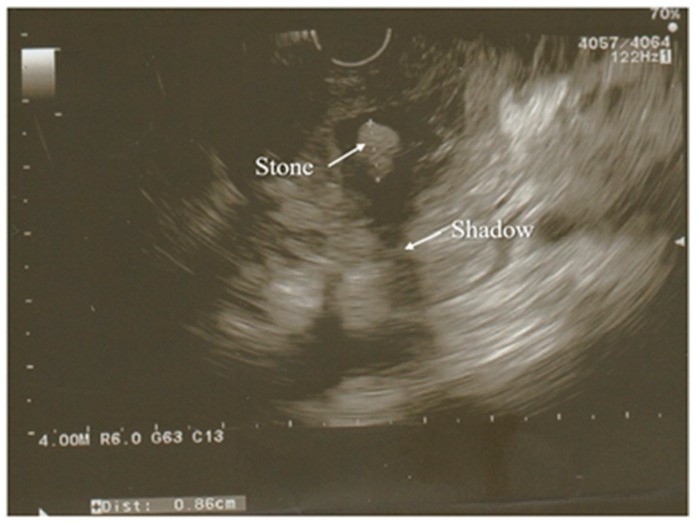

Figure 2.

Figure 2: Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) image revealing a partially calcified gallstone in the distal common bile duct, a common cause of pancreatitis. Edematous pancreatic parenchyma is also visible.

3.4. Endoscopic Ultrasonography (EUS)

- Detailed Local Imaging: EUS combines endoscopy and ultrasound, placing an ultrasound probe close to the pancreas for high-resolution images. Think of it as a very precise, targeted ultrasound.

- Microlithiasis and CBD Stones: EUS is highly sensitive for detecting small gallstones (microlithiasis) and common bile duct (CBD) stones, which can be missed by other imaging modalities.

- Etiology Investigation: Especially useful in cases of idiopathic acute pancreatitis (where the cause is unclear) to identify subtle biliary causes.

- Limitations: Invasive procedure, requiring sedation. Not typically used as a first-line imaging test for routine AP diagnosis.

EUS is often used when other imaging is inconclusive, particularly in patients with recurrent pancreatitis of unknown cause, or when biliary obstruction is suspected but not confirmed by other means.

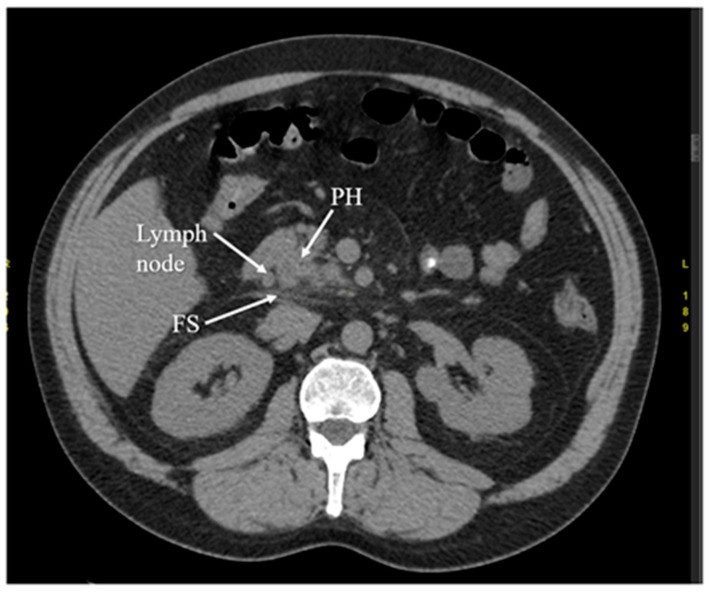

Figure 3.

Figure 3: Arterial phase Computed Tomography (CT) scan in early acute pancreatitis showing fat stranding (FS) around the pancreas and an enlarged lymph node, indicative of inflammation. PH denotes the head of the pancreas.

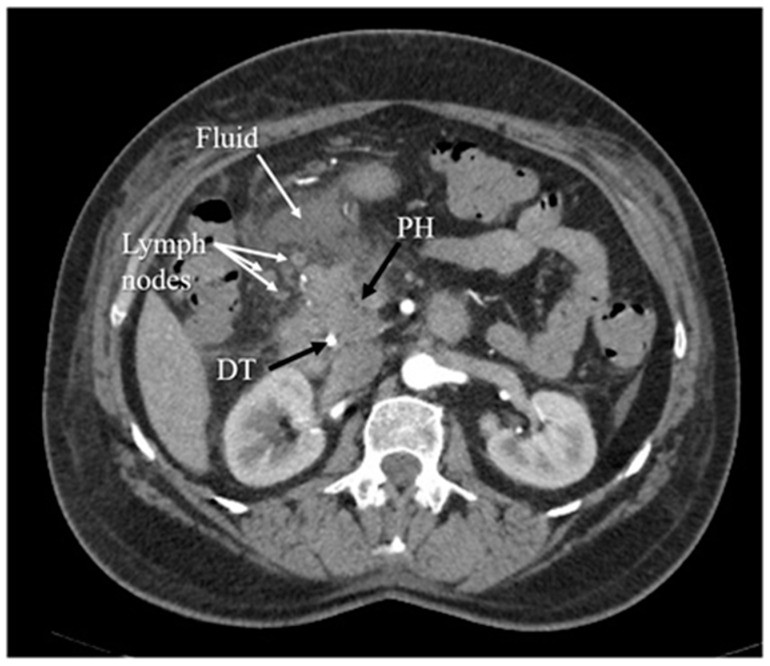

Figure 4.

Figure 4: Arterial phase Computed Tomography (CT) scan showing inflammation of the pancreatic head (PH), with surrounding fluid and enlarged lymph nodes. DT indicates a duodenal tube.

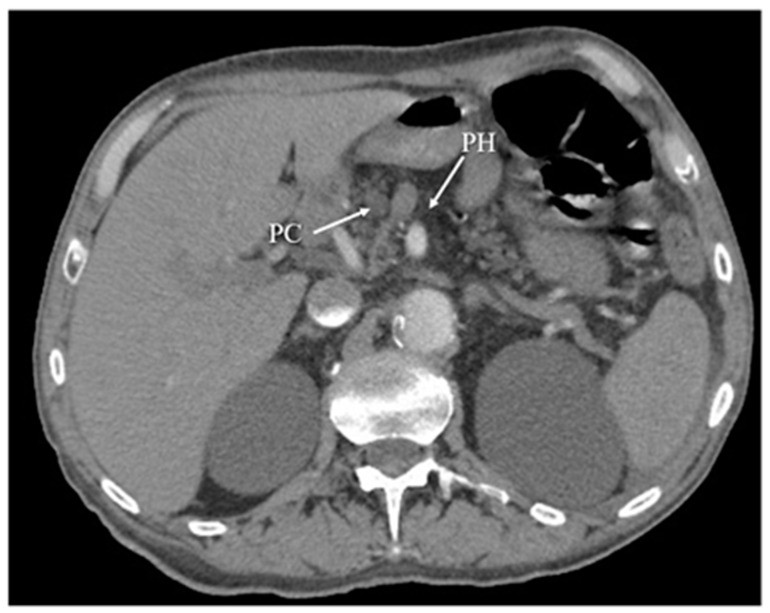

Figure 5.

Figure 5: Arterial phase Computed Tomography (CT) scan illustrating chronic pancreatitis, characterized by atrophy of the pancreatic head (PH) and a pseudocyst (PC) in the same region.

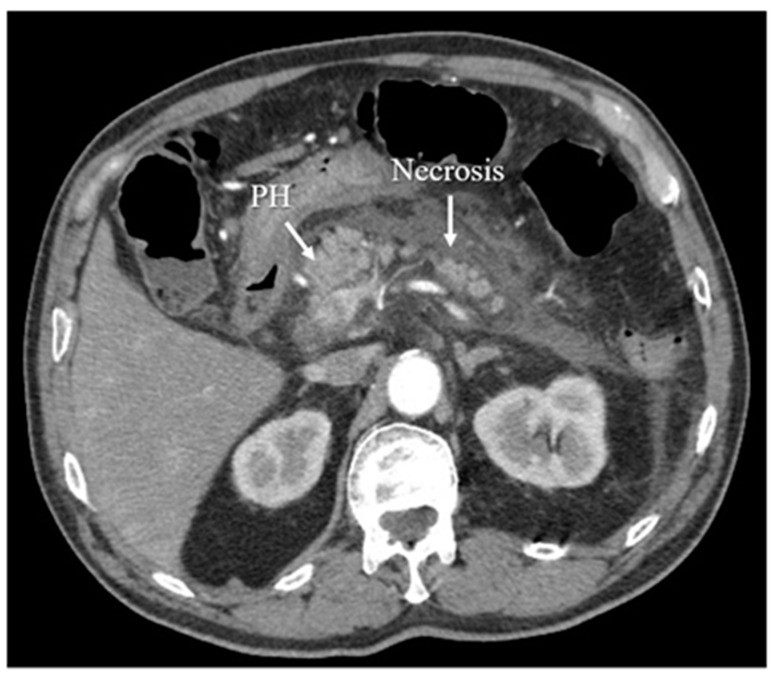

Figure 6.

Figure 6: Arterial phase Computed Tomography (CT) scan demonstrating acute necrotizing pancreatitis, a severe form of the disease involving tissue death.

Differential Diagnosis: Ruling Out Other Conditions

It’s crucial to differentiate pancreatitis from other conditions that can mimic its symptoms. Just like a car might have multiple issues causing similar warning lights, abdominal pain and elevated enzymes can be due to other problems. Conditions to consider include:

- Other Abdominal Emergencies: Appendicitis, cholecystitis (gallbladder inflammation), peptic ulcer disease, bowel obstruction, and mesenteric ischemia can present with abdominal pain.

- Non-Pancreatic Causes of Elevated Enzymes: Kidney failure, bowel obstruction, and certain medications can also raise amylase and lipase levels.

- Chronic Pancreatitis Exacerbation: Patients with chronic pancreatitis can have acute flare-ups that resemble acute pancreatitis.

A thorough clinical evaluation, including history, physical exam, and appropriate investigations, is essential to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

Severity Assessment and Classification

Once acute pancreatitis is diagnosed, assessing its severity is crucial for guiding treatment. The Revised Atlanta Classification is the most widely used system, categorizing AP into:

- Mild Acute Pancreatitis: No organ failure, no local or systemic complications. Usually resolves within a week.

- Moderately Severe Acute Pancreatitis: Transient organ failure (resolves within 48 hours) and/or local or systemic complications without persistent organ failure.

- Severe Acute Pancreatitis: Persistent organ failure (lasting longer than 48 hours).

Severity assessment involves clinical parameters, laboratory tests, and imaging findings. Scoring systems like BISAP, APACHE II, and CTSI are used to predict severity and prognosis.

Table 1. Classification of Acute Pancreatitis Based on 2012 Atlanta Classification

| Severity of Acute Pancreatitis | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Mild Acute Pancreatitis | The most frequent form; No organ failure; No local or systemic complications; Usually resolves in the first week |

| Moderately Severe AP | Transient organ failure (resolving within 48 h); Local or systemic complications without persistent organ failure; Exacerbation of co-morbid disease |

| Severe Acute Pancreatitis | Persistent organ failure > 48 h |

| Criterion of Acute Pancreatitis | Characteristics |

| Organ failure and systemic complications of acute pancreatitis | Respiratory System: Pao2/FiO2 ≤ 300; Cardiovascular System: systolic blood pressure not fluid responsive or pH <7.0; Urinary System: serum creatinine ≥ 170 μmol/L |

| Local complications of acute pancreatitis | Acute peripancreatic fluid collections; Pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis (sterile or infected); Pancreatic pseudocyst; Walled-off pancreatic necrosis (sterile or infected) |

Etiology: Identifying the Cause

Determining the cause of pancreatitis is important for management and prevention of recurrence. The most common causes are:

- Gallstones: Blockage of the bile duct by gallstones is the leading cause.

- Alcohol Abuse: Chronic heavy alcohol consumption is another major contributor.

Other less common causes include:

- Hypertriglyceridemia: High levels of triglycerides in the blood.

- Medications: Certain drugs can induce pancreatitis.

- Post-ERCP Pancreatitis: A complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

- Autoimmune Pancreatitis: An autoimmune condition affecting the pancreas.

- Pancreatic Tumors or Cysts: Rarely, these can cause pancreatitis.

- Idiopathic Pancreatitis: In some cases, the cause remains unknown after thorough investigation.

Initial evaluation should include a detailed history (alcohol use, medications, prior episodes), physical examination, liver function tests, calcium, triglycerides, and right upper quadrant ultrasonography to look for gallstones.

Conclusion: Accurate Diagnosis is Key

Diagnosing acute pancreatitis relies on a combination of clinical assessment, laboratory investigations, and radiological imaging. Meeting at least two of the three main criteria – characteristic abdominal pain, elevated pancreatic enzymes, and suggestive imaging findings – is generally required for diagnosis. Understanding these criteria for diagnosis of pancreatitis is crucial for prompt and effective management, ultimately improving patient outcomes and preventing severe complications. Just like a precise diagnosis is the first step in repairing a complex machine, accurate pancreatitis diagnosis is the foundation for effective treatment and recovery.

Author Contributions

J.W.—project development, data collection and management, data analysis, and manuscript writing; N.Z.—data analysis and manuscript editing; M.P.—data analysis and manuscript editing; R.S.T.—data analysis and manuscript editing; J.D.-R.—data analysis and manuscript editing; Ł.O.—data collection, data analysis, and manuscript editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact authors for data requests (Łukasz Olewnik—email address: [email protected]).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding Statement

The authors have no financial or personal relationship with any third party whose interests could be positively or negatively influenced by the article’s content. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[References] (references.md) (Please note: Due to the request to keep the response concise and within this single markdown file, the extensive list of references from the original article is omitted here to maintain brevity. In a real-world scenario, these references would be crucial and should be included, potentially in a separate references.md file as indicated here, or directly within the markdown if preferred.)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact authors for data requests (Łukasz Olewnik—email address: [email protected]).