Anxiety disorders represent the most common spectrum of mental health conditions globally. Often overshadowed by conditions like schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar disorder in public discourse, anxiety disorders can be equally debilitating, significantly impacting an individual’s quality of life, productivity, and overall well-being. The diagnostic landscape for anxiety disorders is continually evolving, with ongoing revisions aimed at refining classifications for more effective clinical treatment and research. Historically, both dimensional and structural diagnostic approaches have been utilized and debated, including proposals for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM-5). However, each method presents inherent limitations. Contemporary diagnostic emphasis is increasingly shifting towards neuroimaging and genetic research, driven by the necessity for a more holistic understanding of the intricate interplay between biological factors, stress responses, and genetic predispositions in shaping anxiety symptoms. This shift towards a more biologically informed understanding is crucial for developing targeted and effective “Current Diagnosis Treatment” strategies.

Anxiety disorders are demonstrably responsive to treatment, with both psychopharmacological interventions and cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT) showing significant efficacy. These therapeutic approaches, however, target different facets of the symptomatic presentation of anxiety. Therefore, exploring and refining logical combinations of these strategies is paramount to optimize treatment outcomes. The field is also witnessing exciting advancements in alternative management approaches for anxiety and strategies for addressing treatment-resistant cases. Future enhancements in treatment protocols should prioritize the development of user-friendly algorithms, particularly for implementation in primary care settings, and place a greater emphasis on mitigating functional impairment experienced by individuals with anxiety.

INTRODUCTION

Anxiety disorders affect a substantial portion of the population, with prevalence rates reaching up to 13.3% in the United States, establishing them as the most prevalent category within mental disorders.1 The widespread nature of these conditions was initially highlighted in the Epidemiological Catchments Area study approximately 26 years ago.2 Despite their extensive prevalence, anxiety disorders have not consistently garnered the same level of recognition and resource allocation as other major mental health syndromes, such as mood and psychotic disorders. Compounding this issue, primary care physicians often serve as the principal point of assessment and treatment.3,4 This management context can lead to significant societal consequences, with anxiety disorders contributing to decreased productivity, increased morbidity and mortality rates, and a rise in substance abuse within a considerable segment of the population.5–7

The anxiety disorders as classified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., text revision (DSM IV-TR) are detailed in Table 1.8

Table 1.

Anxiety Disorders

| Panic disorder (PD) |

|---|

| Specifier: with or without agoraphobia |

| Panic disorder with agoraphobia (AG, PDA) |

| Social phobia (SP) |

| Specifier: generalized |

| Specific phobias (SPP) |

| Specifier: animal, environmental, blood-injection injury, situational type |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) |

| Specifier: acute versus chronic, with delayed onset |

| Acute stress disorder |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) |

| Specifier: with poor insight |

| Anxiety disorders due to: |

| Specifier: with generalized anxiety, with panic attacks, with obsessive–compulsive symptoms |

Significant progress in anxiety research over the past decade is expected to be reflected in the diagnostic criteria modifications within the DSM-5,9 which was published in May 2013. Notably, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) have been reclassified into separate domains: Trauma and Stressor Related Disorders, and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, respectively.10,11 This re-categorization highlights the evolving understanding of these conditions and their distinct etiologies and clinical presentations.

This article aims to comprehensively review the diagnostic challenges inherent in anxiety disorders, propose a model elucidating the development and progression of anxiety symptoms over time, emphasize the neurotransmitter systems implicated in these disorders, and critically evaluate the roles and comparative effectiveness of both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. By addressing these key areas, this review seeks to provide a robust overview of the “current diagnosis treatment” landscape for anxiety disorders.

DIAGNOSTIC DILEMMAS

Over the past decade, epidemiological data has been instrumental in attempts to refine the diagnostic boundaries of anxiety disorders. This iterative process has been evident in the evolution from DSM III through IIIR and DSM IV-TR (as shown in Table 1), culminating in DSM-5. However, the high prevalence of comorbidities in patients with anxiety, as revealed by the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS),11 has significantly complicated these refinement efforts. For example, comorbidity is more the norm than the exception in conditions like Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD).12 In both clinical settings and research studies, it is common to observe the coexistence of multiple diagnosable conditions within a single patient, or at least a symptomatic overlap with several sub-syndromal states. This is particularly pronounced in the symptomatic overlap between various anxiety disorders, depression, and substance use disorders.13

Another complicating factor is the sequential emergence of different disorders in the same individual throughout their lifespan. For instance, an initial diagnosis of panic disorder might resolve following treatment, only to be succeeded years later by symptoms more consistent with OCD or GAD. Whether this pattern reflects an underlying predisposition or distinct, sequential entities remains unclear. This diagnostic fluidity poses a significant challenge for long-term patient management and underscores the need for dynamic diagnostic models.

Furthermore, a significant limitation in the current classification of anxiety disorders is the lack of identified etiological factors and specific treatments tailored to different diagnostic categories. Molecular biological research into the genetic underpinnings of anxiety disorders has not yet yielded a single gene or gene cluster definitively linked as an etiological factor for any specific anxiety disorder. While some genetic findings exist for OCD and panic disorder,14,15 the genetic architecture of anxiety disorders appears to be complex and polygenic. Despite the absence of disorder-specific genetic markers, family and twin studies highlight the significant role of genetic factors, potentially shared across various anxiety disorders, depression, and substance abuse.16 This shared genetic vulnerability suggests common underlying biological mechanisms.

Despite these diagnostic ambiguities, the development of effective serotonergic medications that demonstrate efficacy across a range of categorical disorders (including mood and anxiety disorders) has prompted suggestions for a dimensional model as a more relevant framework for studying and treating these conditions.17 In this dimensional perspective, an anxiety disorder is viewed as a complex constellation of co-occurring symptom dimensions (e.g., panic, social anxiety, and obsessions). Each dimension can vary in severity, potentially influenced by biological or genetic factors, which might necessitate distinct biological or psychological treatment strategies.9 The relative utility of dimensional versus categorical approaches remains a subject of considerable debate in both research and clinical practice and forms a foundational consideration in the development of DSM-5.18,19 The ongoing discussion reflects the field’s efforts to improve the precision and clinical utility of diagnostic systems for anxiety disorders.

Within psychiatry, observed similarities between distinct disorders have led to the concept of “spectrum” disorders, initially conceptualized for OCD.20 This framework has been valuable in evaluating treatment responses and has expanded to encompass spectra such as social anxiety, panic-agoraphobia, and post-traumatic disorders.21–23 While useful, this approach can also be overly broad and potentially misleading, as it may group disorders with limited commonalities, such as pathological gambling and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) within the same OCD spectrum. To date, limited genetic or neuro-circuitry research has validated the extensive spectrum concept.

Dimensional and categorical diagnoses in DSM-IV-TR are typically derived from cross-sectional comparisons of distinct subject groups. However, clinical presentations are observed in individuals treated longitudinally and may be more accurately understood as part of a psychopathological process evolving over time. For example, while a patient might initially meet OCD criteria based solely on obsessions or compulsions, compulsions often emerge later in the disorder’s progression, seemingly as a compensatory mechanism to manage the threat and anxiety associated with obsessive thoughts.24 This temporal dimension is critical for a nuanced understanding of anxiety disorders.

Analogous perspectives can be found in general medicine, where symptoms often represent a combination of a pathogenic agent and the body’s response. For instance, in pulmonary tuberculosis, the lungs react to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by forming scar tissue. While initially containing the infection (potentially evading early clinical detection), this compensatory strategy can become detrimental if excessive, leading to respiratory compromise. This parallel underscores the importance of considering both the primary pathology and the body’s adaptive responses in understanding and treating anxiety disorders.

In recent years, a growing consensus among scientists and clinicians suggests shared underlying mechanisms for anxiety and fear across different anxiety disorders. This recognition has spurred the implementation of standardized treatment protocols in primary care settings25 and the development of the unified theory of anxiety.26 These initiatives reflect a shift toward more generalized and transdiagnostic approaches in the “current diagnosis treatment” of anxiety.

THE ‘ABC’ MODEL OF ANXIETY

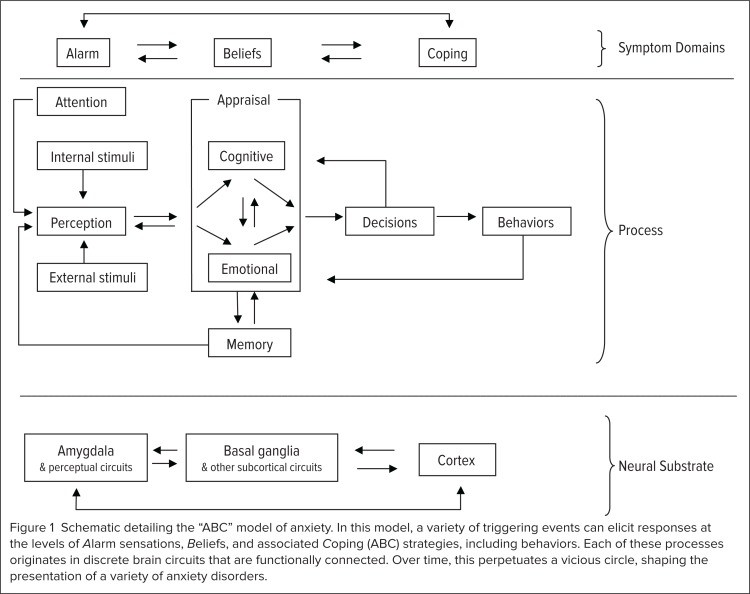

To achieve more precise diagnoses and enhanced management of anxiety disorders, understanding the dynamic interplay between emotional reactivity, core beliefs, and coping strategies over time is crucial. We have previously employed a mathematical model using nonlinear dynamics to describe these processes27 and further refined this model to account for diagnostic presentations and their underlying mechanisms.28 This model, termed the “ABC model of anxiety” for simplicity, posits an interaction across space and time between alarms, beliefs, and coping strategies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the ABC model of anxiety, illustrating the interaction between Alarms, Beliefs, and Coping strategies in perpetuating anxiety disorders. In this model, a range of triggering events can initiate responses at the levels of Alarm sensations, Beliefs, and associated Coping (ABC) strategies, including behaviors. These processes originate in distinct but functionally connected brain circuits. Over time, this interaction can create a self-perpetuating cycle, shaping the manifestation of various anxiety disorders.

Alarms (A) are defined as emotional sensations or physiological responses to a triggering situation, sensation, or thought. A specific network of brain circuits is responsible for rapidly processing information related to these alarms. The amygdala and associated brainstem structures play a crucial role in this alarm system, initiating the body’s immediate response to perceived threats.

The subsequent decision to act is based on beliefs (B), which are heavily influenced by prior experiences, personal and cultural backgrounds, and sensory information. Individuals with anxiety disorders often exhibit heightened and more focused attention on information perceived as dangerous compared to those without anxiety.29 This heightened vigilance, while intended to protect, can become maladaptive. Accurate decision-making regarding beliefs can be obscured by an overwhelming influx of details, leading to catastrophic thinking and indecisiveness. This cognitive distortion is a key feature of anxiety disorders, where perceived threats are often exaggerated and misinterpreted.

This distorted perception, in turn, leads to coping strategies (C), encompassing specific behaviors or mental activities aimed at reducing anxiety and avoiding the perceived “danger.” Coping strategies can be classified as adaptive or maladaptive based on their effectiveness in reducing the targeted anxiety. Adaptive coping strategies effectively reduce anxiety without significant negative consequences, while maladaptive strategies, though providing temporary relief, can perpetuate the anxiety cycle or create new problems. These ABC processes evolve over time, shaping the complex clinical picture of a specific anxiety disorder. Understanding these dynamics is essential for tailoring “current diagnosis treatment” approaches.

For instance, panic disorder may begin with an initial, overwhelming panic attack triggered by the activation of the brain’s alarm networks. This event triggers circuits processing danger-related information, and coupled with personal beliefs about the event (e.g., fear of heart attack or death), it leads to increased health and safety concerns. This, in turn, motivates specific coping attempts to mitigate the perceived danger, such as seeking medical evaluations, which may initially alleviate fear.

However, in individuals with panic disorder, standard medical reassurance is often insufficient to fully quell their anxiety due to a need for absolute certainty of “no danger,” which is unattainable. Consequently, worry and anticipation of future attacks persist. The patient then adopts more extensive “safety” behaviors, such as repeated medical examinations (reassurance seeking) and always being accompanied by a “safe” person.

Unfortunately, because absolute safety is elusive, these behaviors tend to become more pervasive and chronic in an attempt to manage the persistent anxiety. The continued presence of anxiety reinforces worry and distress, perpetuating the vicious cycle of the disorder (recurrent panic attacks). If this pattern remains uninterrupted, it can escalate to more inappropriate coping behaviors, such as avoidance of potential panic triggers (agoraphobia), potentially leading to comorbid despair and depression. Most anxiety disorders follow this general ABC process, although the predominant stages may vary across different disorders. For example, ritualistic behaviors are more characteristic of OCD, while avoidance is a hallmark of social anxiety disorder.

We have observed that patients readily understand and identify their symptom patterns within the ABC model. We effectively integrate this model with medication and behavioral techniques, as detailed in prior research.30 Furthermore, we have found the ABC model particularly valuable in teaching psychiatric residents. This model enables residents to grasp and begin implementing cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) within a relatively short timeframe. By providing a clear and intuitive framework, the ABC model enhances both patient understanding and clinician training in the “current diagnosis treatment” of anxiety disorders.

Interplay Between Biological and Psychological Factors

To effectively treat anxiety disorders, clinicians must understand their origins and the factors maintaining them. Recent advances have significantly improved our understanding of the interaction between genetic, biological, and stress factors that shape the presentation of these disorders, although the precise nature of inherited vulnerabilities remains under investigation.

One hypothesis suggests that abnormal cognition could be an inherited factor. Cognitive theory emphasizes the primary role of abnormal or “catastrophic” cognition as a fundamental mechanism across all anxiety disorders. Many cognitive treatment and research strategies were developed based on this premise. Catastrophic misinterpretations of bodily sensations or external events are central to many anxiety disorders, driving the cycle of fear and avoidance.

The ABC model emphasizes the interaction between information processing and emotional and cognitive processes, all regulated by overlapping brain circuits that compete for neural resources.27 This competition highlights the complex interplay between different brain systems in anxiety.

In most anxiety disorders, individuals tend to process fear-inducing information with excessive detail, overwhelming their capacity for proper appraisal. They often resort to binary thinking, categorizing information into “good” or “bad” with limited nuance. This rigid categorization leads to worst-case scenario thinking (catastrophizing), prompting protective actions against perceived dangers. This cognitive bias towards negativity and threat exaggeration is a core component of anxiety disorders.

Stress

Stress significantly contributes to the pathology of anxiety disorders. PTSD, for example, is defined by stress as the primary etiological factor, although patients with PTSD often report high levels of co-occurring stress. In other anxiety disorders, such as GAD and OCD, the role of stress may be less overtly defined but remains significant. Patients across anxiety disorder diagnoses frequently identify the onset of their condition in relation to a significant stressful event or ongoing stressors. Whether stress is a primary cause or a consequence, heightened stress reactivity can contribute to relapses in chronic anxiety conditions like GAD. Some studies suggest that stressful events or chronic stress can induce secondary biological alterations in specific brain structures.31,32 This biological embedding of stress responses further complicates the “current diagnosis treatment” landscape.

The current DSM-IV-TR system does not adequately address the role of stressors in anxiety disorders. While stressors are identified separately on Axis IV of the multiaxial system, the contextual relevance for the patient is often unclear. A more effective approach to assessing stress in anxiety might involve specifying the source, persistence (immediate, intermittent, or constant), and severity (mild, moderate, severe, or catastrophic) of the stressor. This detailed assessment could provide a more nuanced understanding of the stress landscape and its dynamic impact on anxiety. For example, panic disorder stemming from combat trauma may differ clinically from panic disorder triggered by chronic work-related stress or family separation. Further research into how stress influences the biology and course of anxiety disorders is clearly needed to refine “current diagnosis treatment” strategies.

Biological Factors

Biological factors are fundamentally important in anxiety disorders. Anxiety disorders can manifest in the context of underlying medical illnesses,33 necessitating careful consideration of the intricate relationship between medical conditions and anxiety. This relationship is multifaceted.

Firstly, metabolic or autonomic abnormalities caused by medical illnesses can directly induce anxiety syndromes. For example, hyperthyroidism can trigger panic attacks. Secondly, symptoms of a medical illness can act as triggers for anxiety. Sensations of cardiac arrhythmia, for instance, can precipitate a panic attack. Thirdly, medical illnesses can sometimes mimic anxiety disorders. Perseverative behaviors in intellectual disability might be misdiagnosed as OCD.

Finally, medical illness and an anxiety disorder can simply co-exist in the same patient. One particularly intriguing interaction is Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS), reported in a subset of OCD patients.34 These complex interactions underscore the importance of comprehensive medical and psychiatric evaluations in the “current diagnosis treatment” of anxiety.

Over the past two decades, biological research in anxiety disorders has shifted from peripheral measures of autonomic and neurochemical parameters to directly investigating brain reactivity and neurochemistry using advanced neuroimaging technologies. Anxiety disorders are particularly well-suited for neuroimaging research because specific symptoms can be readily provoked in many cases. Much of this research on neural circuits has been guided by established models of anxiety and fear proposed by basic scientists,35,36 with syntheses of current data attempted for panic disorder37 and OCD.38 These neuroimaging studies are crucial for refining our understanding of the neural substrates of anxiety and informing more targeted “current diagnosis treatment” approaches.

Excellent reviews of neuroimaging experiments in anxiety are available,39,40 yet the picture remains incomplete, partly due to a scarcity of clinical trials examining the long-term integration of threat responses. Consistent with the dynamical ABC model, each anxiety disorder can be viewed as an interplay of anxious feelings, abnormal information processing, and inadequate coping strategies. Correspondingly, overlapping neuronal circuits are responsible for alarm reactions, threat processing, and behavioral coping (see Figure 1). This model simplifies complex brain circuitry, requiring extensive study over the coming decades to fully elucidate how the brain processes threats over time.

For simplicity, we categorize these circuits into Alarm circuits (A), where the amygdala is central. These circuits also include the periaqueductal gray matter and multiple brainstem nuclei.41 Dysfunction in these alarm circuits can lower the threshold for alarm reactions, leading to spontaneous panic attacks. These circuits are likely responsible for the rapid initial response to threats.

Circuits associated with Beliefs (B), involved in processing “threat” information, are likely closely linked to the basal ganglia, cingulum, and corticostriatal connections, typically implicated in OCD. These circuits are involved in higher-order cognitive processing of potential threats and the formation of beliefs about danger.

Abnormalities in Coping (C) are likely governed by distributed cortical networks and are more complex to isolate. Therefore, a useful mnemonic for these circuits is A (Alarm, amygdala), B (Beliefs, basal ganglia), and C (Coping, cortex). This simplified model provides a framework for understanding the neural basis of anxiety and for developing more targeted “current diagnosis treatment” strategies.

How Anxiety Affects Neurotransmitters

Neuronal circuits are regulated by multiple neurotransmitter systems, with gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate being the most prevalent. The neural systems of three major neurotransmitter systems—serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine—have been extensively investigated in both normal and pathological anxiety states.40,42 The significance of these systems in anxiety is evident in the fact that most effective therapies for anxiety disorders modulate one or more of them. However, anxiety disorders are not simply caused by a deficiency or excess of a single neurotransmitter. The networks governed by these transmitters have complex interrelationships, feedback mechanisms, and receptor structures.43 This complexity contributes to the unpredictable and sometimes paradoxical responses to medications and highlights the need for personalized “current diagnosis treatment” approaches.

Research into other neurotransmitter systems has provided valuable insights into their roles in anxiety but has not yet translated into new treatments. The primary neurotransmitter and receptor systems implicated in the pathogenesis of anxiety disorders are discussed below.

Serotonin

The primary serotonergic pathways originate in the raphe nuclei and project widely throughout the forebrain.44 These circuits are fundamental in regulating brain states, including anxiety, and also modulate dopaminergic and noradrenergic pathways.45 Increased serotonergic activity appears to be associated with reduced anxiety, although the precise mechanism remains unclear. Serotonin’s role in mood regulation and anxiety is well-established, making it a primary target for pharmacological interventions in the “current diagnosis treatment” of anxiety disorders.

Numerous serotonin receptor subtypes exist, each with potentially varying roles depending on their location. For example, the serotonin-1a receptor can act as both a mediator and an inhibitor of serotonergic neurotransmission, depending on whether it is located on the presynaptic or postsynaptic neuron.46 Furthermore, not all serotonin receptor subtypes mediate anxiolytic effects, as demonstrated by the fact that serotonin-2a receptor agonism is responsible for the psychedelic properties of drugs like LSD and mescaline.47 This receptor subtype complexity underscores the challenges in developing highly specific serotonergic medications for anxiety.

Despite this complexity, it is well-established that medications inhibiting serotonin reuptake, thus increasing serotonergic neurotransmission, effectively reduce anxiety symptoms in many patients.48 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a cornerstone of pharmacological “current diagnosis treatment” for various anxiety disorders.

Gamma-aminobutyric Acid

GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS). Increased GABA neurotransmission mediates the anxiolytic effects of barbiturates and benzodiazepines.49 These medications do not directly bind to the GABA receptor itself; instead, they enhance the open configuration of an associated chloride channel. Barbiturates increase the duration of channel opening, while benzodiazepines increase the frequency of opening. By enhancing GABAergic inhibition, these drugs effectively reduce neuronal excitability and anxiety.

While modulating GABAergic pathways can provide rapid anxiety relief, compensatory mechanisms within these circuits and the use of barbiturates and benzodiazepines can lead to tolerance and potentially life-threatening withdrawal syndromes.50 Furthermore, these drugs can impair memory encoding, potentially hindering the effectiveness of concurrent psychotherapy. These limitations restrict their role in the long-term “current diagnosis treatment” of anxiety disorders.

Anticonvulsant agents also modulate GABA transmission and are used to treat anxiety.51 This class of medications indirectly affects GABA transmission by blocking calcium channels, resulting in a lower risk of withdrawal and addiction compared to benzodiazepines.52 Agents like pregabalin and gabapentin are increasingly used in the “current diagnosis treatment” of anxiety, particularly for generalized anxiety disorder.

Dopamine

The primary dopaminergic pathways originate in the midbrain (ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra) and project to the cortex, striatum, limbic nuclei, and infundibulum. Dopamine’s role in normal and pathological anxiety states is intricate, and dopaminergic pathways can influence anxiety in multiple ways.53 Dopamine D2 receptor blockade, the mechanism of antipsychotic medications, is known to be anxiolytic.54 This explains why some antipsychotics are used off-label for anxiety management.

While dopamine receptor blockade can reduce anxiety, dopamine, as a catecholamine, is also upregulated alongside norepinephrine in anxiety states. Conversely, increased dopaminergic signaling appears to mediate feelings of self-efficacy and confidence, which can, in turn, reduce anxiety.55, 56 This complexity results in variable responses to dopamine-modulating medications. Some patients with anxiety disorders respond favorably to pro-dopaminergic drugs like bupropion (Wellbutrin), while others experience symptom exacerbation. This variability necessitates careful patient selection and monitoring in the “current diagnosis treatment” utilizing dopaminergic agents.

Norepinephrine

Noradrenergic neurons primarily originate in the locus coeruleus in the pons and project widely throughout the CNS.57 Similar to dopamine, norepinephrine is a catecholamine upregulated in anxiety states, but it has a complex, potentially bidirectional role in mediating normal and pathological anxiety. Many physiological symptoms of anxiety are mediated by norepinephrine, and antagonists of various norepinephrine receptor subtypes are used to manage specific anxiety aspects.

For example, propranolol, a beta2-norepinephrine receptor antagonist, is used to alleviate physiological symptoms like rapid heart rate, tremor, and voice quivering associated with performance anxiety.58 While effective for these physical manifestations of anxiety, propranolol is less effective in addressing the emotional and cognitive dimensions of anxiety and is not typically used as a primary therapy for anxiety disorders.

Similarly, prazosin (Minipress), an alpha1-norepinephrine receptor antagonist, is used to reduce nightmares associated with PTSD but has not proven effective for other anxiety disorder symptoms.59,60 Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as venlafaxine (Effexor) and duloxetine (Cymbalta), are effective in treating anxiety disorders.61 These medications also help reduce neuropathic pain and may target the agonal component of anxiety. SNRIs represent a valuable class in the pharmacological “current diagnosis treatment” of anxiety disorders, particularly when SSRIs are insufficient.

Glutamate

Glutamate is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the CNS and is involved in virtually all neuronal pathways, including those underlying normal and pathological anxiety states.62,63 The N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subtype is particularly relevant to anxiety disorders as it is believed to mediate learning and memory processes. NMDA receptor activation triggers protein synthesis, strengthening neuronal connections when they fire concurrently. Thus, glutamatergic pathways are likely involved in both conditioning and extinction, processes central to the development and treatment of anxiety disorders.64 This role in synaptic plasticity makes glutamate a key target for understanding and treating anxiety.

Preliminary evidence suggests that both enhancing and antagonizing NMDA-mediated pathways can be effective in treating anxiety disorders, although no glutamatergic medications are currently FDA-approved for this indication. D-cycloserine, which enhances glutamatergic neurotransmission, has shown promise in augmenting exposure therapy for anxiety disorders.65 Conversely, NMDA receptor antagonists like memantine (Namenda) and riluzole (Rilutek) have shown efficacy in treating OCD.66 Interestingly, memantine appears less effective in GAD treatment, suggesting distinct underlying pathways for different anxiety disorders.67 Glutamatergic modulation holds potential for future “current diagnosis treatment” strategies, but further research is needed.

Other Neurotransmitters

Numerous other neurotransmitter systems participate in the biological mechanisms of fear and anxiety. Neuropeptides, including substances P, N, and Y; corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF); cannabinoids; and others, modulate fear responses in animal models.68–70 However, none of the experimental agents targeting these systems have yet been translated into FDA-approved treatments.71 Stringent approval criteria and high placebo response rates in anxiety trials may contribute to this translational gap.72 Continued research into these systems may uncover novel therapeutic targets for “current diagnosis treatment”.

PHARMACOLOGICAL THERAPY

While numerous neurotransmitters play a role in anxiety, relatively few medication classes are routinely used in clinical practice for anxiety treatment. These established drug classes are briefly reviewed below, representing the mainstay of pharmacological “current diagnosis treatment”.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

SSRIs, typically indicated for depression, are considered first-line therapy for many anxiety disorders. This class includes fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), citalopram (Celexa), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluvoxamine (Luvox), paroxetine (Paxil), and vilazodone (Viibryd).72 The defining characteristic of SSRIs is their inhibition of the serotonin transporter, leading to presumed desensitization of postsynaptic serotonin receptors and normalization of serotonergic pathway activity.

The precise mechanism by which SSRIs alleviate anxiety symptoms is not fully understood. Vilazodone, the most recently approved SSRI (indicated for major depressive disorder), also acts as a partial agonist at the serotonin-1a receptor, potentially contributing to its anxiolytic effects.73 Buspirone (BuSpar), while not an SRI, is a 5-HT1a agonist and is often used as monotherapy or as augmentation to SSRI treatment.74 SSRIs are foundational in the “current diagnosis treatment” algorithms for various anxiety disorders.

Serotonin–Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors

SNRIs, which inhibit both serotonin and norepinephrine transporters, include venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine (Pristiq), and duloxetine.75 Milnacipran (Savella) is rarely used for anxiety, primarily indicated for fibromyalgia.76 SNRIs are typically considered after inadequate response to SSRIs or as augmentation strategies. Combining SSRIs and SNRIs is generally avoided due to the risk of serotonin syndrome.

Patient responses to SNRIs can vary. Some may experience worsened physiological anxiety symptoms due to increased norepinephrine signaling from norepinephrine transporter inhibition. However, for others, increased noradrenergic tone may contribute to the anxiolytic efficacy. SNRIs are a crucial second-line option in the “current diagnosis treatment” of anxiety, offering a broader neurotransmitter modulation.

Benzodiazepines

While historically widely used, benzodiazepines are no longer considered first-line therapies for anxiety due to risks associated with chronic use.75 They are highly effective for acute anxiety relief but carry significant adverse effects with long-term, high-dose use, including:

- Physiological and psychological dependence.

- Potentially fatal withdrawal syndromes.

- Cognitive and coordination impairment.

- Risk of lethal overdose when combined with alcohol or opioids.

- Inhibition of memory encoding, interfering with psychotherapy efficacy.

These risks limit benzodiazepine use to short-term treatment of acute anxiety or as a last resort for treatment-refractory anxiety after other drug trials have failed. However, some patient subgroups may benefit from low-dose benzodiazepines and can safely taper off, especially with concurrent CBT.77 Benzodiazepines remain a tool in the “current diagnosis treatment” arsenal, but with carefully considered and limited application.

Antiseizure Medications

Due to benzodiazepine side effects, antiseizure agents have gained prominence in anxiety treatment. Initially used for mood stabilization, their anxiolytic properties were quickly recognized. Many antiseizure drugs are used off-label for anxiety, particularly gabapentin (Neurontin) and pregabalin (Lyrica).51,78 Less data exists for topiramate (Topamax), lamotrigine (Lamictal), and valproate (Depacon).79 At higher doses, antiseizure medications can produce side effects similar to benzodiazepines.80 They represent a valuable alternative, especially for patients with substance use history or concerns about benzodiazepine dependence in “current diagnosis treatment”.

Tricyclic Antidepressants

All tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) inhibit norepinephrine reuptake, and some also inhibit serotonin reuptake. While comparable in efficacy to SSRIs or SNRIs for anxiety, TCAs have a greater side effect burden and are potentially lethal in overdose. Consequently, TCAs are rarely used for anxiety disorders, with a notable exception being clomipramine (Anafranil), potentially more effective than SSRIs or SNRIs for OCD.81 TCAs are generally reserved for specific cases, primarily OCD, in “current diagnosis treatment”.

Additional Medications

Hydroxyzine (Atarax), mirtazapine (Remeron), nefazodone (Bristol-Myers Squibb), and atypical neuroleptics are also used to treat anxiety.82 While effective, especially for OCD, they are not first-line and are typically adjuncts to SSRIs or SNRIs. Hydroxyzine, indicated for anxiety, likely exerts its anxiolytic effect by inhibiting histamine H1 and serotonin-2a receptors.83 These medications provide additional options, particularly for augmentation strategies in “current diagnosis treatment”.

TREATMENT STRATEGIES

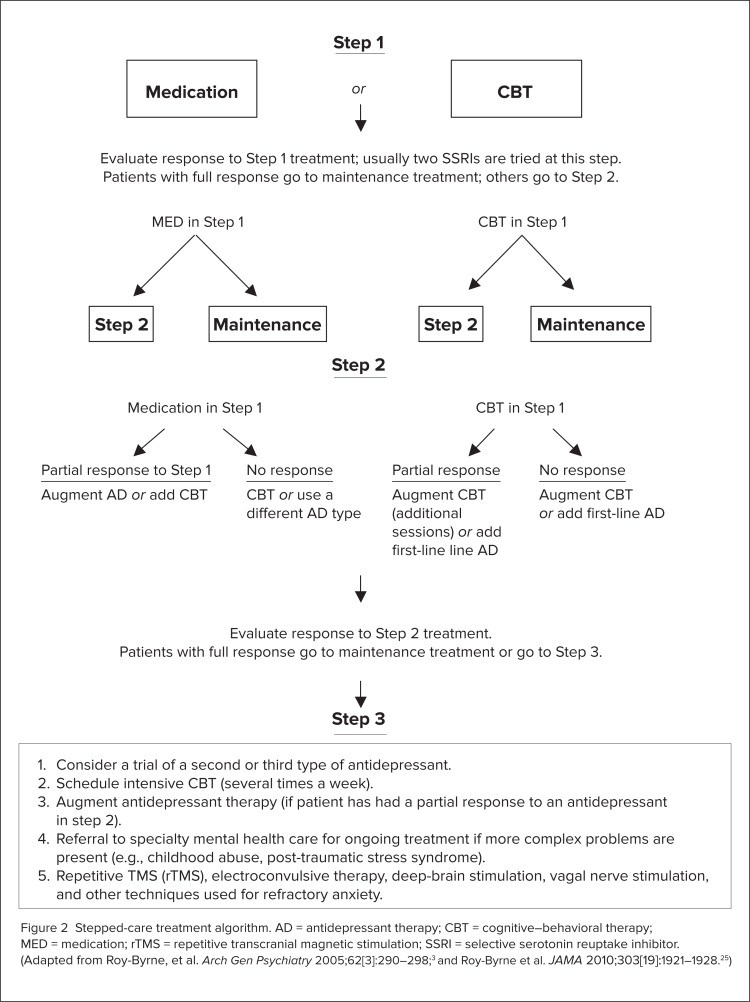

Initial Treatment Algorithms

During the 1990s, mainstream psychological and pharmacological treatments for anxiety disorders were developed and validated, leading to a generally consistent initial treatment algorithm for major anxiety disorders.84,85 A typical algorithm, adapted from Roy-Byrne et al.,25 is presented in Figure 2. This algorithm represents a stepped approach to “current diagnosis treatment”.

Figure 2.

Stepped-care treatment algorithm for anxiety disorders, outlining the progression from initial treatments like CBT and SSRIs to more advanced strategies for treatment-resistant cases. AD = antidepressant therapy; CBT = cognitive–behavioral therapy; MED = medication; rTMS = repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. (Adapted from Roy-Byrne, et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62[3]:290–298;3 and Roy-Byrne et al. JAMA 2010;303[19]:1921–1928.25)

Generally, clinicians choose between CBT and an SSRI as initial monotherapy, switching to another SSRI if the first is ineffective or poorly tolerated. No SSRI has demonstrated superior efficacy over others. SSRI selection is typically based on side effect profiles, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, and potential interactions with other medications. This individualized approach is critical in “current diagnosis treatment”.

Several excellent reviews of SSRI therapies for anxiety disorders are available.86 A general SSRI principle is to “start low and go slow,” initiating treatment at approximately half the antidepressant dose and gradually titrating upwards, with dosage changes no more frequent than weekly. This gradual titration minimizes initial side effects and improves tolerability.

Antidepressants with broader mechanisms of action, like venlafaxine and clomipramine, are considered for non-responders. This rationale is based on their multi-neurotransmitter effects and meta-analytic data suggesting potential superiority in depression and OCD.87 Benzodiazepines are generally avoided except in acute states or treatment-resistant chronic conditions, reflecting their limited role in long-term management.

Limited data exists on subsequent treatment steps, such as maintenance therapy duration. Clinical experience suggests continuing treatment until marked symptom reduction is sustained for at least 6 months. Further research is needed to optimize maintenance strategies and relapse prevention in “current diagnosis treatment”.

Further research has examined combined treatments at initial and later stages of these algorithms.88,89 In later treatment stages, GABAergic antiepileptic drugs and atypical antipsychotics may be considered. Atypical neuroleptics have shown promising efficacy in placebo-controlled anxiety disorder trials.90 These augmentation strategies are essential for managing treatment-resistant cases.

Side Effect Profiles

Patients and physicians must be aware of potential adverse drug reactions. Valuck published an extensive review of SSRI side effects.91 Studies have linked SSRIs and SNRIs to increased suicidality risk92, and atypical neuroleptics to tardive dyskinesia and arrhythmias.93 Weight gain and sexual dysfunction are potential side effects across these drug classes. With polypharmacy becoming increasingly common, especially in complex and treatment-resistant anxiety, practitioners must be vigilant about potential drug-drug interactions.94 Careful side effect monitoring and management are integral to effective “current diagnosis treatment”.

Serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome, while rare, should be considered. SSRI discontinuation can lead to withdrawal syndrome, including paresthesias, dizziness, nausea, diaphoresis, and rebound anxiety.95 SSRI and SNRI cessation should involve gradual tapering, ideally concurrent with CBT. Gradual discontinuation minimizes withdrawal symptoms and facilitates smoother transition in “current diagnosis treatment”.

Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy and Medications

CBT has the strongest empirical evidence base for psychological treatment of anxiety disorders.96 Our treatment algorithm positions CBT alongside SSRIs as a first-line treatment choice (see Figure 2). Combination therapy (medication and CBT) has shown mixed results compared to monotherapy, with outcomes varying by anxiety disorder type.

A meta-analysis comparing combination treatment to monotherapy (medication or CBT) in anxiety hypothesized that CBT would be more effective than medication, while medication would be more advantageous for depression.97 Within anxiety disorders, responsiveness to CBT or medication varied considerably, with CBT showing superiority in panic disorder, while medication was more effective for social anxiety disorder. This highlights the importance of tailoring “current diagnosis treatment” to specific anxiety disorders.

The choice between medication, CBT, or combination therapy depends on factors like therapist availability, CBT affordability (more expensive than medication, especially in primary care), and patient preference. Patient access, cost, and individual needs are critical determinants in treatment selection.

Cognitive Behavior Therapy Alone

Suboptimal anxiety disorder treatment is partly due to CBT therapist scarcity and session affordability. Distilling effective therapy elements and integrating them into primary care settings, emphasizing education and staff training, is crucial.25 Oxford University Press offers excellent therapist and patient manuals for CBT.98 Internet-based self-administered therapies are proliferating, necessitating further efficacy research.99 Complex anxiety disorders may not be suitable for self-treatment, while specific phobias might be manageable alone or with support. Self-directed CBT and online resources are expanding access to psychological “current diagnosis treatment”.

Koszycki et al.100 investigated self-administered CBT alone versus therapist-directed CBT, self-administered CBT, or medication augmented with self-administered CBT. Their findings suggested that even self-administered CBT could be a valuable addition to the CBT armamentarium. This underscores the potential of scalable, self-help CBT approaches.

While numerous effective anxiety treatments exist, no single treatment works for everyone or all anxiety disorders. Simple phobias are more readily treated than complex PTSD. SSRIs and CBT are the most empirically supported treatments. CBT relapse rates compared to medication are understudied, but clinical experience suggests CBT offers longer-lasting effects if patients continue utilizing learned skills. Long-term effectiveness and relapse prevention are key considerations in “current diagnosis treatment”.

Technique

CBT shares common ground with more psychodynamic psychotherapies. Patients seek help from a skilled caregiver in a supportive relationship to improve functioning and well-being in a reality-oriented context. However, CBT is directive and collaborative; therapists set clear, specific goals with patients and use evidence-based techniques to explore feelings, bodily sensations (Alarms), dysfunctional cognitions (Beliefs), and behaviors (Coping). The ABC model provides a framework for understanding and addressing these components.

While the therapeutic relationship is less emphasized as a curative factor in CBT compared to other therapies, it is crucial for building trust and rapport, enabling patients to examine maladaptive beliefs and behaviors contributing to anxiety. Therapists explicitly conceptualize the patient’s disorder, addressing genesis, evolution, and maintenance over time. Manuals and psychoeducational materials are often incorporated, and daily homework assignments may be given to facilitate adaptive anxiety management, belief modification, and coping mechanism development, often through exposure exercises. Patients are ideally taught the ABC model to understand the dynamic interplay between feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. Patient education and active participation are central to CBT’s effectiveness in “current diagnosis treatment”.

Patient compliance directly correlates with treatment effectiveness. Motivational interviewing, examining the cost-benefit ratio of maladaptive thoughts and behaviors, can enhance compliance and efficacy.101 Patients learn self-monitoring and symptom-reduction techniques to increase motivation to confront anxiety. Breathing and relaxation techniques are taught as mental hygiene to raise the threshold for alarm reactivity and enhance awareness of escalating alarm reactions. Self-management skills and motivational enhancement are key aspects of CBT.

The linchpin of CBT for anxiety is considered to be patient’s thoughts.102 Modifying misguided beliefs is essential for down-regulating alarms and fostering adaptive coping, replacing avoidance and escape-based behaviors. While beliefs are central, exposure to anxiety-provoking stimuli (thoughts, images, situations) is often the core CBT component for shifting these beliefs. Cognitive restructuring techniques targeting catastrophic thinking help reduce irrational cognitions, increasing willingness to test beliefs through exposure exercises. Cognitive and behavioral techniques are intertwined and essential for effective CBT.

Exposure

Exposure involves the gradual, systematic presentation of anxiety-inducing stimuli (thoughts, images, or situations) for sufficient duration to allow patients to experience anxiety reduction without avoidance or escape behaviors. For example, a dog-phobic patient might progress from viewing dog pictures to standing across from a pet shop, and eventually holding a dog. Each step is repeated until anxiety gradually diminishes before advancing. Gradual, repeated exposure is key to habituation and anxiety reduction.

Ideally, patients experience gradual anxiety reduction at each step before progressing. They experience alarm reduction, and the exaggerated belief (e.g., “all dogs are dangerous”) can be modified towards a more accurate belief (e.g., “most pet dogs are not threatening”). The desired outcome is eliminating phobic avoidance of dogs. Successful exposure therapy restructures maladaptive beliefs and reduces avoidance behavior, central to CBT’s “current diagnosis treatment” approach.

Mindfulness (The Third Wave)

A recent evolution in CBT is mindfulness-based approaches (acceptance-based therapies), representing the “third wave” of CBT. The first wave was strict behavior therapy, the second emphasized cognitive therapy.103 Mindfulness-based therapies integrate principles of Eastern meditative practices with Western cognitive and behavioral techniques.

Mindfulness, derived from Buddhist psychology, is defined as “awareness of present experience with acceptance.”103 These therapies are indebted to Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program, initiated at the University of Massachusetts in 1979.104 MBSR and related mindfulness-based interventions have gained significant traction in mental health.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is one integration of mindfulness into CBT.105 MBCT has been applied to panic disorder and other anxiety disorders, but further controlled research is needed.106 MBCT emphasizes relapse prevention through meta-cognitive, mindful awareness, helping patients recognize that current symptoms do not necessarily indicate relapse. Mindfulness-based approaches are increasingly recognized for their relapse prevention benefits in “current diagnosis treatment”.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) incorporates a mindful focus; exercises aim at the meta-cognitive level, helping patients perceive thoughts and anxiety as separate from their self-concept. Anxiety-provoking thoughts are to be observed and accepted, not struggled against or changed, contrasting with traditional CBT and Western psychology.107 Acceptance and commitment are central tenets of ACT, promoting psychological flexibility and reducing avoidance.

Shifting Treatment to Primary Care

In managed care environments, anxiety treatment increasingly occurs in primary care settings. Primary care physicians’ time constraints contribute to under-recognition and under-treatment of anxiety disorders. Simultaneously, SSRIs (antidepressants) are increasingly prescribed in primary care, with physicians being the largest prescriber group. This presents a mixed picture: increased access to medication but potential challenges in comprehensive care.

- SSRIs are sometimes prescribed quickly for emotional distress that may not meet anxiety disorder criteria.

- Therapy dose and duration may be inadequate.

- Adverse effects may be managed solely by treatment discontinuation.

This scenario may partly explain why psychiatrists see more patients disillusioned with numerous failed pharmacotherapy attempts. Primary care’s role in “current diagnosis treatment” is expanding, but challenges in comprehensive management exist.

Another primary care issue is limited understanding of behavioral strategies, resulting in low mental health professional referral rates. A trend exists towards developing comprehensive panic disorder treatments deliverable by primary care physicians. Integrating behavioral health into primary care is crucial for improving access to comprehensive “current diagnosis treatment”.

One study tested a panic disorder treatment algorithm for primary care.108 This reflects a trend of psychiatrists becoming consultants to primary care physicians, assisting with initial management and managing severe, treatment-resistant anxiety. Collaborative care models are emerging to enhance primary care’s capacity for effective anxiety management.

Management of Treatment-Resistant Anxiety

Managing refractory anxiety requires re-evaluating the patient, including diagnosis, comorbidities, and cognitive, stress-related, and biological factor interplay. Patient and family coping strategies should be reviewed. Initial treatment doses and durations should be assessed to ensure adequate trials. Comprehensive re-evaluation is the first step in managing treatment resistance.

Initially, more intensive CBT, combined with adequate SSRI, SNRI, or combination trials, may be needed for refractory anxiety. Subsequent treatment might progress to SSRI combination with antiepileptic or atypical neuroleptic agents, especially if bipolar or psychotic disorders are suspected.109,110 Partial hospitalization in specialized centers with intensive CBT and medication management may be recommended later.111 Stepped-care intensification and multidisciplinary approaches are essential for treatment-resistant anxiety.

While other therapy forms lack demonstrated anxiety disorder efficacy, they may address personality issues in chronically anxious patients. Addressing comorbid personality traits can improve overall treatment outcomes in complex cases.

Experimental and Off-Label Nonpharmacological Treatments

Anxiety disorder therapies beyond conventional treatments, off-label agents (antiepileptics, antipsychotics), and intensive CBT, are largely experimental. Promising medications have included intravenous clomipramine, citalopram, and morphine.109 Many other treatments targeting specific neurotransmitter systems have failed.72 Research into novel pharmacological targets continues, but clinical translation remains challenging.

A few invasive therapies have emerged for treatment-resistant cases with significant functional impairment, particularly severe OCD. These target brain circuits involved in fear and anxiety processing. Invasive procedures are reserved for the most refractory cases after exhausting conventional and off-label options.

Electroconvulsive Therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) involves brief electrical scalp impulses inducing widespread neuronal discharge and generalized seizure activity. While effective for treatment-resistant mood disorders, limited data exists on ECT efficacy in anxiety disorders.112 ECT mechanisms and focal targets remain unclear. ECT is a last-resort option for severe, treatment-resistant anxiety disorders.

Vagal Nerve Stimulation

Vagal nerve stimulation (VNS), initially developed for epilepsy, was used in psychiatric patients after mood improvements were noted.113 VNS is thought to stimulate brain networks relevant to anxiety and fear processing (amygdala, hippocampus, insula, orbitofrontal cortex) via the afferent vagal nerve. VNS is not routinely used for anxiety, and evidence of effectiveness in resistant anxiety is limited.114 No randomized controlled trials have further investigated this intervention. VNS remains experimental for anxiety, with limited evidence of efficacy.

Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

Focal magnetic scalp stimulation aims to excite or inhibit cortical neurons. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is less invasive than ECT; anesthesia is unnecessary, and rTMS does not induce generalized seizures. It can target brain regions implicated in anxiety disorders. rTMS offers a more targeted and less invasive neuromodulation approach.

rTMS limitations include inability to penetrate deep brain structures involved in OCD (caudate nucleus, thalamus, anterior capsule) or panic disorder (amygdala, hippocampus, anterior cingulate) and lack of stimulation site specificity. Deep brain targets are challenging to reach with rTMS.

rTMS is not approved for any anxiety disorder, likely due to limited large-scale studies. Limited evidence suggests efficacy in OCD, with larger effects reported by altering stimulation sites.115,116 rTMS has reportedly improved anxiety symptoms in PTSD and panic disorder, but is not yet clinical practice.117 A small study reported anxiety reductions in GAD using symptom-provocation fMRI to guide rTMS site selection.118 No studies have investigated rTMS in social anxiety disorder. rTMS shows promise, particularly for OCD and potentially GAD, but further research is needed for clinical translation.

Surgery

Psychosurgery has been used for treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (GAD, panic disorder, social phobia), but long-term follow-up revealed adverse cognitive outcomes, including apathy and frontal lobe dysfunction.119 Surgical approaches are now primarily reserved for OCD due to its significant functional deficits in refractory cases. Psychosurgery is a highly invasive last resort for severe, treatment-refractory OCD.

Several surgical approaches exist: anterior capsulotomy (anterior internal capsule), anterior cingulotomy (anterior cingulate and cingulum bundle), subcaudate tractotomy (substantia innominata), and limbic leucotomy (cingulotomy + subcaudate tractotomy).120,121 Cingulotomy is the most common psychosurgical procedure in North America, likely due to efficacy and lower morbidity/mortality. Cingulotomy is considered the safest and most widely used psychosurgical option for OCD.

Postoperative effects can include transient headache, nausea, or urinary difficulty. Postoperative seizures, the most serious common side effect, are reported in 1-9% of cases. Careful patient selection and monitoring are crucial.

Patient outcomes are assessed at least 6 months to 2 years post-procedure, suggesting postoperative neural reorganization is important for recovery. Direct comparisons of lesion approaches are rare. Long-term outcomes show significant therapeutic effects across procedures, with response rates ranging from 30-70% in remission, response, and functional quality of life improvements. Psychosurgery can offer significant relief for severely affected OCD patients unresponsive to other treatments.

Deep-Brain Stimulation

Deep-brain stimulation (DBS) involves implanting small electrodes under stereotactic MRI guidance. DBS advantage over ablative surgery is adjustable neurostimulation.122 Electrode stimulation parameters (polarity, intensity, frequency, laterality) can be modified and optimized by trained clinicians during long-term follow-up. DBS offers adjustable and reversible neuromodulation, a key advantage over ablative surgery.

Blinded stimulation studies have shown moderate-to-fair results.123 More recently, structures adjacent to the internal capsule have been targeted.124,125 Response rates are consistently reported around 50% in trials.125 DBS shows promise for treatment-resistant OCD, with ongoing research to optimize targets and stimulation parameters.

Postoperative complications (infections, lead malfunctions) are more common with DBS due to its prosthetic nature. Battery replacements are periodically needed. Stimulation-related side effects include mood changes (transient sadness, anxiety, euphoria, hypomania), sensory disturbances (olfactory, gustatory, motor), and cognitive changes (confusion, forgetfulness). These are typically stimulation-dependent and resolve with parameter adjustments. Careful surgical technique and long-term management are needed for DBS.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

During the 1990s, numerous alternative anxiety disorder treatments emerged.126 These include herbal medications (St. John’s wort most common), vitamins, nutritional supplements, magnetic and EEG synchronizing devices, “energy” treatments, and meditation-based therapies (Mindfulness). CAM represents a broad spectrum of non-conventional approaches to anxiety management.

These treatments may be provided by alternative medicine practitioners (acupuncture, homeopathy, Ayurvedic medicine, Reiki, healing touch). Due to minimal FDA regulation and over-the-counter availability, many patients self-select and use these treatments. Herbs are the most common CAM products, particularly popular among those with psychiatric disorders. Anxiety is a strong predictor of herbal remedy use,127 and patients often use them without physician knowledge. Clinicians and pharmacists should regularly monitor patients’ full treatment regimens, including prescription, non-prescription, herbs, and supplements at each visit. Open communication about CAM use is crucial for patient safety and integrated care.

Herbal trial results for anxiety disorders are mixed. Piper methysticum (Kava) use for anxiety was curtailed by hepatotoxicity reports, leading to government warnings and market withdrawal in many Western countries.128,129 However, a randomized placebo crossover trial using a supposedly benign aqueous formulation reported moderate anxiety symptom reductions in a small mixed anxiety disorder sample.128,130 Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort) and Silybum marianum (milk thistle) have been used for OCD symptoms, but placebo-controlled trials showed no significant symptom differences or adverse effects between treatment groups.131,132 Lower-quality CAM studies reported modest treatment effects for mindfulness meditation, yoga, and acupuncture.133 Evidence for CAM efficacy in anxiety disorders is generally weak and inconsistent.

Despite limited efficacy data, many patients continue using CAM therapies, necessitating monitoring for potential interactions with prescription medications.134 St. John’s wort interacts with many medications by inducing cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes 3A4 and 2C9. CYP3A4 induction can decrease alprazolam (Xanax) and clonazepam (Klonopin) serum levels. Combining St. John’s wort with SSRIs increases serotonin syndrome risk. Milk thistle inhibits CYP3A4, potentially increasing levels of other medications metabolized by this pathway. Kava has been linked to inhibiting several CYP isoenzymes (1A2, 2D6, 2C9, 3A4).135 Further research on alternative anxiety strategy efficacy is needed, but caution regarding interactions is paramount in “current diagnosis treatment”.

Functional Status

While many anxiety disorder patients experience symptom relief with treatment, residual symptoms can still impact daily function. Even subclinical anxiety can cause disability exceeding that seen in severe mental illnesses.111,136 Chronic, persistent anxiety disorders significantly impact lives, often causing social and work skill deficits. Few interventions or programs specifically target rehabilitation and functional restoration in these patients. Functional outcomes and rehabilitation are under-addressed aspects of “current diagnosis treatment”.

Stress significantly contributes to anxiety syndromes. Patients returning to work can experience increased stress, potentially causing symptom re-emergence, reduced productivity, and job loss. More research is needed to address this. Vocational rehabilitation and stress management strategies are needed to improve functional outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Anxiety disorders are treatable. Effective treatments and refined algorithms exist. However, further progress requires integrating our understanding of anxiety biological mechanisms with treatment to better predict and improve treatment response. Dynamic anxiety models—like the ABC model—are helpful for understanding symptom development, maintenance, and biological-psychological interplay over time. A more integrated and personalized approach to “current diagnosis treatment” is essential.

We must improve delivery of effective treatments in real-world healthcare settings, like primary care, and educate the public via media. Continued testing of alternative therapies for anxiety treatment and prevention and assisting patients with treatment-resistant anxiety are crucial. Enhancing access to evidence-based care and public awareness are key priorities.

Finally, we must consider patient feelings about mental illness and address them early in treatment. All these measures will enhance anxiety patient care. Addressing stigma and promoting patient-centered care are vital for improving “current diagnosis treatment” outcomes.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Bystritsky reports that he has received honoraria, research grants, and travel reimbursements from AstraZeneca, Takeda, and Brainsway. He has also served as a consultant for UpToDate, John Wiley & Sons, Brainsonix Corp., and Consumer Brands. Dr. Khalsa, Dr. Cameron, and Dr. Schi3man report that they have no financial or commercial relationships in regard to this article. This work was supported in part by a grant from the Saban Family Foundation.