Cushing’s Syndrome (CS) can be a challenging condition to diagnose, particularly in its early stages. Often overlooked, despite its significant health implications, timely diagnosis in primary care settings is crucial to mitigate associated morbidities and mortality. This article aims to provide an enhanced guide for primary care clinicians on recognizing and diagnosing Cushing’s Syndrome, emphasizing the importance of early detection and appropriate screening strategies.

Why Early Cushing Syndrome Diagnosis Matters

Endogenous Cushing’s Syndrome, while historically considered rare, may be more prevalent than previously thought, especially in certain age groups. Characterized by excessive cortisol production, CS can be broadly categorized as ACTH-dependent (driven by pituitary adenomas or ectopic tumors) or ACTH-independent (typically adrenal in origin). Regardless of the cause, undiagnosed and untreated Cushing’s Syndrome carries substantial risks. The condition is associated with a range of serious physical and psychological health issues and significant comorbidities. Historically, before effective treatments were available, the 5-year mortality rate was alarmingly high, underscoring the critical need for prompt diagnosis and intervention.

Recognizing Cushing’s Syndrome in Primary Care: When to Suspect

Cushing’s Syndrome can manifest at any age, but the likelihood of specific subtypes can vary across patient demographics. For instance, pituitary-related Cushing’s is more frequently observed in younger women, while ectopic ACTH production might be more suspected in older individuals, particularly smokers.

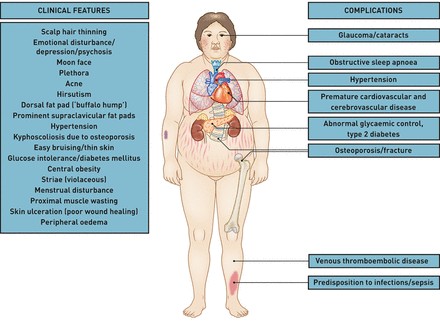

The classic Cushingoid appearance, while striking, represents the more advanced stages of the condition. Many patients in primary care present with subtler signs and symptoms, which may only become fully apparent in retrospect after successful treatment of hypercortisolism. Reviewing a patient’s older photographs can sometimes reveal noticeable changes in appearance over time, offering valuable clues.

Figure 1: Clinical features and associated comorbidities commonly observed in Cushing’s syndrome patients.

A significant challenge in timely diagnosis is the potential failure to recognize the importance of symptom clusters and linked comorbidities. The appearance of conditions like early-onset hypertension, diabetes mellitus, unexplained venous thromboembolism (VTE), or osteoporosis, especially in younger individuals, should raise suspicion for Cushing’s Syndrome. Similarly, dermatological signs such as violaceous striae, easy bruising, thinning skin, adult-onset acne coupled with facial redness (plethora) and a rounded face (“moon face”), alongside musculoskeletal symptoms like muscle weakness and proximal myopathy, warrant further investigation for hypercortisolism. Recognizing these diverse presentations is key to effective Cushing syndrome diagnosis in primary care.

Effective Screening Tests for Cushing’s Syndrome in General Practice

No single diagnostic test perfectly identifies Cushing’s Syndrome. Clinical guidelines typically suggest a suite of screening options, each with its own advantages and limitations. Common first-line tests include the overnight dexamethasone suppression test (O/N DST), 24-hour urinary free cortisol (UFC) measurement, and late-night salivary cortisol (LNSC) assessment.

Figure 2 provides a guide on performing and interpreting these initial screening tests, as well as key considerations for test selection in primary care. Despite perceptions of complexity, the O/N DST is a safe, effective, and often preferred initial screening tool for many endocrinologists in the primary care setting. It’s important to differentiate the O/N DST from the more complex 48-hour dexamethasone suppression tests, including the low-dose DST (LDDST) used for confirming or excluding CS, and the high-dose DST (HDDST) used to differentiate between pituitary and ectopic ACTH sources in specialized settings.

Figure 2: Overview of common screening tests used in the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome in primary care settings.

Referral to Secondary Care: When is it Necessary?

Diagnosing Cushing’s Syndrome can be an evolving process. Initial presentations may be ambiguous, and the diagnosis often becomes clearer as the condition progresses or with further investigation. A period of watchful observation might be appropriate in some cases. When considering referral to an endocrinologist, assessing the clinical suspicion level (low, intermediate, or high) alongside initial screening test results is helpful.

For instance:

- Low clinical suspicion and a negative screening test: Referral is likely unnecessary.

- Low clinical suspicion but a positive screening test (without an obvious cause for a false positive): Referral is recommended.

- Intermediate to high clinical suspicion: Proceed with a screening test and arrange for referral concurrently.

These guidelines help streamline the referral process for suspected Cushing syndrome diagnosis in primary care.

Future Directions in Cushing’s Syndrome Diagnosis in Primary Care

Given the rarity of Cushing’s Syndrome and the breadth of symptoms seen in primary care, it’s not feasible to screen every patient presenting with potentially related but common symptoms. Automated digital health tools offer a promising avenue for improving early detection. Integrating sensitive algorithms into electronic health record systems could help flag potential CS cases by identifying specific patterns of clinical features. Emerging technologies, such as software analyzing facial photographs over time for subtle Cushingoid changes, are also being explored. While the latter assumes CS is already considered, these digital aids can enhance the efficiency of Cushing Syndrome Diagnosis Primary Care pathways.

Key Messages for Primary Care

The potential consequences of untreated hypercortisolism emphasize the importance of considering Cushing’s Syndrome in differential diagnoses. While the investigation of CS might seem complex, the initial screening steps are practical and well-suited for the primary care setting. By increasing awareness and utilizing appropriate screening tools, primary care clinicians play a vital role in the timely Cushing syndrome diagnosis and improving patient outcomes.

References

[1] Lindstedt, K. A., et al. “Incidence of Cushing’s syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98(1): R9-16.

[2] Lacroix, A., et al. “Prevalence of Cushing’s syndrome in patients consulting for obesity, hypertension, diabetes or osteoporosis.” Eur J Endocrinol 2015; 173(6): 763-71.

[3] Plotkin, M., et al. “Mortality in Cushing’s syndrome before and after diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018; 103(10): 3637-47.

[4] Nieman, L. K., et al. “Treatment of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100(8): 2807-31.

[5] Arnaldi, G., et al. “Diagnosis and complications of Cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statement.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88(12): 5593-602.

[6] Fleseriu, M., et al. “Cushing’s syndrome due to adrenocorticotropin secretion.” Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2015; 44(1): 1-20.

[7] আহমেদ, A., et al. “Deep learning for automated detection of facial features of Cushing’s syndrome.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020; 105(5): e1723-32.