Introduction

Endometriosis, alongside adenomyosis, stands as a prevalent benign condition affecting women, second only to uterine fibroids in frequency, with an estimated occurrence rate between 5% and 15%. The past decade has witnessed significant advancements in our understanding and diagnostic capabilities for this disease. Concurrently, progress in treatment methodologies has been matched by an increasing awareness of endometriosis among both patients and healthcare providers. When considering differential diagnoses for pelvic pain and related gynecological issues, especially in women of reproductive age, endometriosis and particularly deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) should be a primary consideration. This article delves into the diagnosis of endometriosis, with a special focus on deep infiltrating endometriosis, providing a comprehensive overview for clinicians and those seeking in-depth knowledge on this condition.

Definition of Endometriosis

Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus. This tissue, similar biologically to the basal endometrial layer, can implant and grow in various locations, most commonly within the pelvic cavity. In rare instances, endometriosis can metastasize to distant organs. These ectopic endometrial implants are composed of glands, stromal cells, and smooth muscle, and are characterized by neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and lymphangiogenesis [1-5]. Crucially, endometriosis lesions express estrogen and progesterone receptors (ER α/β and PR A/B), rendering them responsive to hormonal treatments [6, 7]. While primarily considered a disease of reproductive-age women, endometriosis has been histologically documented even before menarche [4, 8], and postmenopausal cases constitute less than 3% of all diagnoses.

Learning Objectives

This article aims to equip readers with the knowledge to:

- Recognize and describe the primary clinical manifestations of endometriosis.

- Understand the diagnostic evaluation process and classification systems used for endometriosis, particularly focusing on Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis Diagnosis.

- Gain an overview of current curative and palliative treatment strategies available for endometriosis.

Epidemiology of Endometriosis and Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis

The overall prevalence of endometriosis is estimated to be between 5% and 15% among women of reproductive age, with higher rates observed in specific subgroups [2, 4, 6]. Notably, endometriosis is found in 20% to 48% of women experiencing infertility. The prevalence is even higher, around 70%, in young women with chronic pelvic pain unresponsive to hormonal therapy or NSAIDs [4]. Data specific to deep infiltrating intestinal endometriosis and urinary tract endometriosis are less robust. Ureteric endometriosis, for instance, is reported in 0.1% to 0.4% of all endometriosis cases, while urogenital endometriosis overall is estimated at 1% to 2% of all endometriosis cases [9, 10]. These figures underscore the importance of considering DIE in women presenting with relevant symptoms, necessitating a thorough diagnostic approach.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of endometriosis is significant, affecting 5% to 15% of women.

Etiology

The tissue injury and repair concept offers insights into the development of endometriosis.

Etiology and Pathogenesis: Understanding the Development of Endometriosis

While the exact cause of endometriosis remains a subject of ongoing research, the transplantation theory, suggesting retrograde menstruation as a primary mechanism, has been widely considered [11]. Retrograde menstruation involves the flow of menstrual blood containing endometrial cells through the fallopian tubes into the pelvic cavity. However, this theory alone fails to explain why not all women, who commonly experience retrograde menstruation, develop endometriosis.

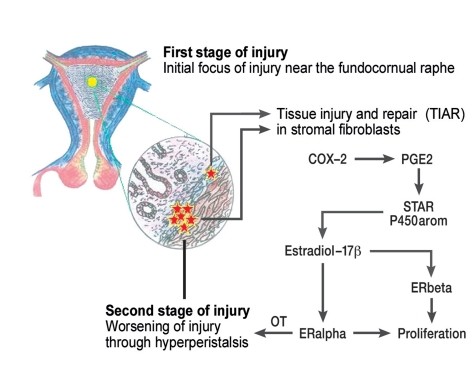

The currently favored etiological hypothesis is the Tissue Injury and Repair (TIAR) concept [7]. This concept highlights the unique embryological development of the uterus, composed of the archimetra (endometrial glands, stroma, subvascular layer) and the neometra (vascular and supravascular layers) [6, 7]. Ultrasonographically, the archimyometrium appears as a hypodense halo, and in MRI, as a hypointense junctional zone [2, 7]. Microtrauma at the interface between these uterine layers, especially in the fundocornual raphe region, can occur due to estrogen-driven peristalsis [7]. The subsequent repair processes are associated with local hyperestrogenism due to aromatase overexpression. This leads to paracrine-estrogen-induced uterine hyper- and dysperistalsis, resulting in desquamation and displacement of basal endometrium through the fallopian tubes into the abdominal cavity (Figure 1) [4, 7]. Simultaneously, basal layer cells can infiltrate the myometrium, leading to adenomyosis. Thus, endometriosis and adenomyosis are considered related conditions [1, 6, 7]. Stem cells within the basal endometrial layer are believed to play a crucial role in both the cyclical regeneration of eutopic endometrial tissue and in the pathogenesis of endometriosis [12]. Current genomic and proteomic research is further elucidating the molecular biology of endometriosis [13], promising advancements in our understanding and management of this complex disease.

Figure 1. Tissue Injury and Repair Concept in Endometriosis Development

Figure 1: Illustrating the Tissue Injury and Repair (TIAR) concept in endometriosis and adenomyosis. The uterus develops from archimetra and neometra interactions. Ovarian function onset increases uterine contractility, causing tissue injury at the fundocornual raphe. Repair processes in the basal endometrium lead to local hyperestrogenism and uterine dysperistalsis, creating a cycle where endometrial tissue is sloughed off (transtubal transport, leading to endometriosis) or proliferates into the myometrium (adenomyosis). Illustration courtesy of Prof. Dr. med. Gerhard Leyendecker.

Clinical Manifestations: Recognizing Symptoms of Endometriosis

Endometriosis presents with a wide array of symptoms, varying in severity and nature. Key manifestations include:

- Pain: This is a hallmark symptom, often associated with menstruation (dysmenorrhea), sexual intercourse (dyspareunia), and defecation (dyschezia). Pelvic pain can be cyclical or chronic.

- Hemorrhagic Disturbances: Irregular or heavy uterine bleeding is common.

- Infertility: Endometriosis is a significant cause of infertility in women.

Major Manifestations of Endometriosis

- Pain related to menstruation, sex, or bowel movements; chronic pelvic pain.

- Uterine bleeding abnormalities.

- Infertility.

Types of Endometriosis

- Bladder endometriosis.

- Ureteric endometriosis.

- Rectovaginal endometriosis.

Diagnostic History and Evaluation for Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis

Diagnosing deep infiltrating endometriosis requires a comprehensive approach, beginning with a detailed patient history and physical examination, supplemented by imaging and, in some cases, invasive procedures.

History Taking: Uncovering Clues from Patient Symptoms

A thorough medical history is crucial in the diagnostic process. It allows the physician to understand the patient’s symptoms in detail and correlate them with physical findings. Key historical aspects to explore include:

- Symptom Dynamics and Timeline: When did symptoms begin? Have they changed over time? Are they cyclical, acyclical, or chronic?

- Menstrual History: Age at menarche, presence of pain with the first periods, impact of menstruation on daily life (school absence, analgesic use, oral contraceptive use).

- Previous Treatments and Surgeries: Past surgeries (gynecological, endometriosis-related, other), endocrine treatments (type, duration, outcome), alternative therapies (acupuncture, TCM, naturopathy, homeopathy – duration and results). Obtaining operative notes from previous surgeries is highly valuable.

- Pain Characteristics: Differentiate between primary and secondary dysmenorrhea. Characterize dyspareunia (position-dependent, position-independent, impact on libido, relationship issues, potential psychogenic factors). Assess pelvic pain (cyclical, acyclical, chronic, perimenstrual back pain).

- Urogenital Symptoms: Inquire about dysuria, polyuria, pollakisuria, irritable bladder symptoms, frequent cystitis, hematuria (micro or macro), perimenstrual incontinence, urinary obstruction, interstitial cystitis-like symptoms.

- Gastrointestinal Symptoms: Investigate constipation, pseudo-diarrhea, postprandial cramps, hematochezia, dyschezia, irritable bowel syndrome-like symptoms, perimenstrual tenesmus, painful bloating, and changes in stool consistency related to the menstrual cycle.

- Psychosomatic and Psychiatric Aspects: Assess for fatigue, depressive symptoms, anxiety, medication abuse, social and relationship problems.

- Past Medical History: Inquire about pre-existing conditions like diabetes, hypertension, depression, thyroid disorders, and their treatments.

- Medication Use: Current and past use of oral contraceptives, GnRH analogues, gestagens, antidepressants, antidiabetic agents, etc.

Gynecological Examination: Physical Assessment for Endometriosis

A careful gynecological examination is essential. Key steps include:

- Speculum Examination: Thorough inspection of anterior and posterior vaginal fornices to identify macroscopic signs of infiltration. Colposcopy may be indicated based on findings. Vaginal biopsy under local anesthesia can be useful if suspicious lesions are observed.

- Rectovaginal Palpation: Crucial for assessing deep infiltrating endometriosis, ideally performed under general anesthesia during a procedure to maximize patient comfort and muscle relaxation.

Ultrasonography: Imaging for Endometriosis Detection

Ultrasonography plays a vital role in the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Different approaches are used:

- Transvaginal Ultrasonography: Primary method for detecting ovarian endometriomas, uterine adenomyosis, and potential bowel involvement.

- Abdominal Ultrasonography: Renal ultrasound and bladder ultrasound (with a full bladder) to evaluate for vesical endometriosis and hydronephrosis secondary to ureteric involvement.

- Transanal Ultrasonography (Endosonography): Combined with rectosigmoidoscopy, this technique is valuable for assessing rectal endometriosis, particularly deep infiltrating lesions, and determining the layers of bowel involvement, especially for proximally located lesions beyond digital palpation reach.

Laboratory Tests: Biomarkers in Endometriosis Diagnosis

While no single lab test definitively diagnoses endometriosis, certain markers can be helpful:

- CA-125: A tumor marker, often elevated in endometriosis, although levels are typically lower than in ovarian cancer. Elevated CA-125 can support the suspicion of endometriosis, especially in active disease, but is not specific.

- Urinalysis and Bacteriology: To rule out urinary tract infections, especially when urogenital symptoms are present.

- β-HCG: Pregnancy test, if relevant to the clinical scenario.

- CRP (C-Reactive Protein): May be elevated in inflammatory conditions, but non-specific for endometriosis.

Advanced Imaging and Invasive Diagnostic Tests for Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis

For suspected deep infiltrating endometriosis, advanced imaging is crucial:

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): The imaging modality of choice for adenomyosis and deep infiltrating endometriosis. MRI excels in visualizing soft tissues and can delineate the extent of disease. For bladder infiltration, MRI with a full bladder is recommended. Contrast-enhanced rectal MRI provides detailed assessment of rectal involvement.

- Intravenous Urography (IVU): Indicated if ureteric involvement is suspected, though often replaced by MRI urography.

- Cystoscopy: Combined with biopsy if bladder endometriosis or interstitial cystitis is suspected. Transurethral resection (TUR) is contraindicated for treating bladder endometriosis.

- Rectosigmoidoscopy: Ideally performed during menstruation. Can be combined with biopsy to assess mucosal involvement in rectal endometriosis.

- Laparoscopy with Histological Confirmation: The gold standard for definitive diagnosis and staging of endometriosis. Laparoscopy is always a surgical procedure, not merely diagnostic. Histological confirmation of endometriosis lesions obtained during laparoscopy is essential for a definitive diagnosis.

- Spiral CT of the Chest: In cases of cyclical hemoptysis (coughing up blood related to menstruation), to rule out rare pulmonary endometriosis.

It’s important to note that current guidelines do not mandate specific diagnostic evaluations for endometriosis. The absence of a definitive recommendation for a particular method should not be interpreted as a recommendation against it. Clinical judgment and individual patient presentation guide the diagnostic pathway.

eBox: Minimum Diagnostic Evaluation for Suspected Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis

History-taking: Detailed assessment of symptoms, their chronology, and impact on patient’s life.

- Historical Aspects: Symptom dynamics, menstrual history, past treatments (surgical, endocrine, alternative), detailed pain characterization (dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain), urogenital and gastrointestinal symptoms, psychosomatic factors, past medical and surgical history, medication use.

Gynecological Examination:

- Speculum examination with vaginal fornices inspection.

- Rectovaginal palpation (ideally under anesthesia if procedure is planned).

Ultrasonography:

- Transvaginal ultrasound: ovarian endometriomas, adenomyosis, bowel involvement.

- Abdominal ultrasound: renal and bladder ultrasound for vesical endometriosis, hydronephrosis.

- Transanal ultrasound: rectal endometriosis, bowel layer involvement.

Laboratory Values:

- CA-125, urinalysis, bacteriology, β-HCG (if needed), CRP.

Imaging and Invasive Tests:

- MRI (preferred over CT) for adenomyosis and deep infiltrating endometriosis. Full bladder MRI for bladder involvement, rectal MRI with contrast for rectal involvement.

- Intravenous urography (if ureteric involvement suspected).

- Cystoscopy with biopsy (if needed, not for TUR).

- Rectosigmoidoscopy (ideally during menses).

- Laparoscopy with histological confirmation (gold standard – always surgical).

- Chest CT (spiral) for cyclical hemoptysis.

Women with endometriosis may also present with gastrointestinal, urological, autonomic, and non-specific symptoms, including fatigue and symptoms resembling chronic fatigue syndrome. Depression and anxiety disorders are common, affecting over 60% of women with diagnosed endometriosis. Therefore, when advanced endometriosis, especially DIE, is diagnosed, psychotherapy should be considered as part of a holistic treatment plan.

Endometriosis of Specific Sites: Bladder, Ureter, and Rectovaginal

Endometriosis can affect various organs, with bladder, ureter, and rectovaginal areas being clinically significant sites for deep infiltrating endometriosis.

Endometriosis of the Bladder

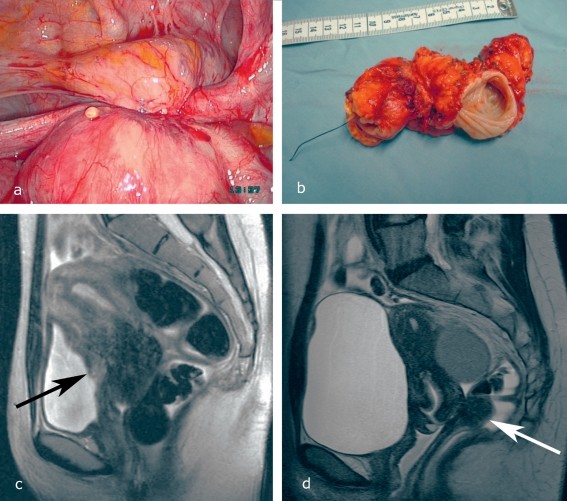

Bladder endometriosis involves infiltration of the bladder wall, often resulting in nodular adenomyofibrohyperplasia (Figure 2a). This can lead to painful and ineffective bladder contractions, as well as microcirculatory disturbances in the urothelium, causing micro- or macrohematuria.

Diagnostic Assessment of Bladder Endometriosis

- History Taking: Focus on urological symptoms like dysuria, hematuria, urinary frequency, and bladder pain.

- Vaginal Palpation: May detect anterior vaginal wall nodules.

- Vaginal Ultrasonography with Full Bladder: Helps visualize bladder lesions and assess infiltration depth (Figure 2c).

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Excellent for detailed imaging of bladder wall infiltration (Figure 2c).

- Cystoscopy: Allows direct visualization of the bladder mucosa and biopsy of intravesical lesions.

- Laparoscopy: Confirms the diagnosis and extent of bladder endometriosis.

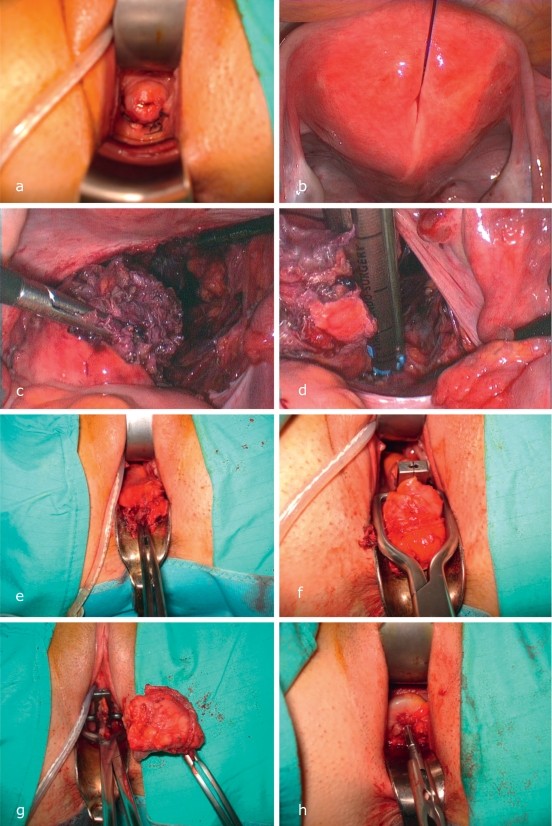

Transurethral resection (TUR) is contraindicated as endometriosis infiltrates from the outer bladder wall inward, making TUR ineffective and potentially harmful (eFigure 1 a-f). Cystoscopy can be used for biopsy and, if needed, insertion of ureteric stents [10, 15].

Figure 2. Typical Varieties of Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis

Figure 2: Demonstrating deep infiltrating endometriosis varieties: (a) Bladder infiltration with round ligament involvement. (b) Stenosing rectal endometriosis. (c) MRI showing bladder infiltration and adenomyosis of the anterior uterine wall (arrow). (d) MRI of uterine adenomyosis and deep infiltrating rectal endometriosis (arrow). Full bladder MRI is crucial for bladder endometriosis diagnosis.

Endometriosis of the Bladder – Renal Ultrasonography Recommendation

Women suspected of bladder endometriosis or any deep infiltrating endometriosis should undergo bilateral renal ultrasonography to assess for hydronephrosis due to potential ureteric involvement.

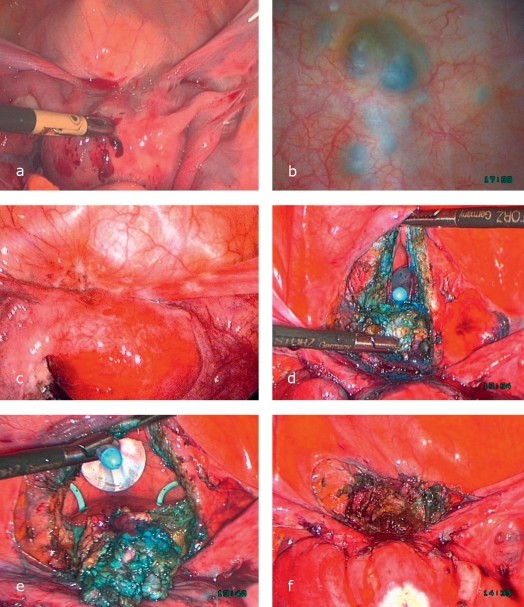

Ureteric Endometriosis

Ureteric endometriosis can be intrinsic or extrinsic [15]. Differentiating between these types preoperatively can be challenging. Extrinsic ureteric endometriosis, more common, involves compression of the ureter from outside by surrounding endometriosis tissue, often associated with bilateral ovarian endometriosis (“kissing ovaries”). The crossing point of the sacrouterine ligament, ureter, and uterine artery is a common site [16] (efigure 2). Intrinsic ureteric endometriosis is rarer and involves infiltration within the ureteric wall itself, occurring in less than 0.3% of endometriosis cases [17].

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis of Ureteric Endometriosis

Manifestations range from non-specific pelvic pain to flank pain, renal obstruction (usually unilateral), and asymptomatic hydronephrosis, potentially leading to kidney function loss.

Recommended diagnostic studies include:

- Renal Ultrasonography: To detect hydronephrosis.

- Intravenous Urogram (IVU) or MRI Excretion Urography: To visualize ureteric obstruction and function. MRI urography is preferred when available.

- Renal Function Tests: Laboratory assessment of creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, and renal scintigraphy to evaluate kidney function.

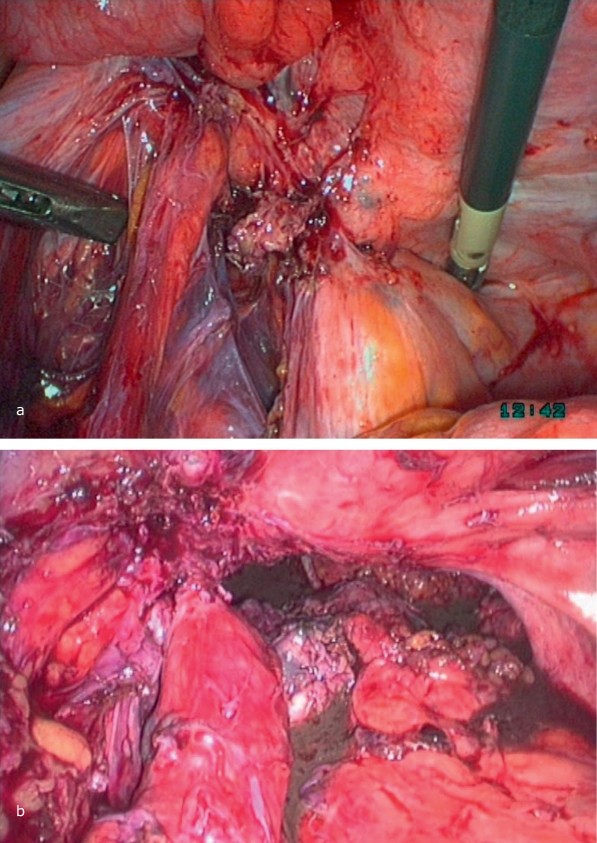

eFigure 2. Extrinsic Ureteric Endometriosis

eFigure 2: Illustrating ureteric endometriosis: (a) Extrinsic involvement of the left ureter with endometriosis infiltrating bowel and right parametria. (b) Intrinsic endometriosis of the left ureter in a 30-year-old woman with a non-visualized kidney, indicating severe obstruction.

Endometriosis of the Ureter – Extrinsic vs. Intrinsic

Ureteric endometriosis can be extrinsic (compression from outside) or intrinsic (rarely, infiltration within the ureter wall).

Rectovaginal Endometriosis

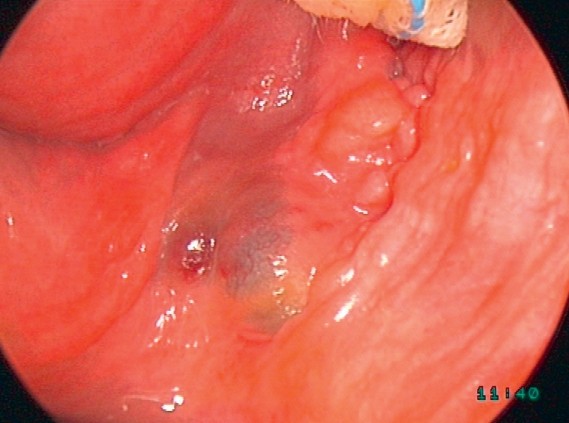

Rectovaginal endometriosis, a common form of deep infiltrating endometriosis, is typically visible in the posterior vaginal fornix and palpable in the rectovaginal septum (Figure 3).

Clinical Features and Diagnosis of Rectovaginal Endometriosis

Infiltration into the adjacent intestine and sacrouterine ligaments, along with adhesions, can cause obliteration of Douglas’s pouch, often contributing to infertility, especially when combined with adenomyosis. Pelvic pain is often severe, intestinal symptoms are common, and dyspareunia, sometimes leading to loss of libido, is typical. These symptoms arise from the location and innervation of the invasive lesions [18]. Bowel endometriosis, particularly transmural infiltration, can lead to stenosis or, rarely, intestinal obstruction (Figure 2b). Abnormal microcirculation in the endometriosis nodule and intestinal mucosa (or mucosal infiltration) can cause cycle-dependent rectal bleeding. Parametrial infiltration often involves the ureters [15, 19], potentially necessitating bilateral ureterolysis and surgical ureter exposure [9, 16, 19].

For optimal preoperative diagnosis:

- History and Rectovaginal Examination: Thorough evaluation as described earlier.

- Transrectal Ultrasonography: Combined with rectosigmoidoscopy, to assess bowel wall involvement and mucosal integrity.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Documents invasive lesions and provides clear evidence of uterine adenomyosis (Figure 2d).

Histological diagnosis and staging are achieved through tissue sampling via laparoscopy or, less commonly today, laparotomy (eBox).

Figure 3. Rectovaginal Endometriosis

Figure 3: Typical infiltration of the posterior vaginal fornix in rectovaginal endometriosis, visible during gynecological examination with correct cervix positioning using a speculum.

Rectovaginal Endometriosis – Diagnostic Visibility

Rectovaginal endometriosis is often readily visible in the posterior vaginal fornix and rectovaginal septum during examination.

Surgical Treatment of Endometriosis and Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis

General Surgical Principles

Endometriosis is a chronic, hormone-dependent condition with variable clinical courses. Treatment must be individualized, considering the patient’s primary needs – whether it’s pain relief or fertility preservation [20, 21]. The biology of endometriosis suggests that a combination of surgery and endocrine therapy (typically anti-estrogenic), complemented by supportive approaches, yields the best outcomes (eTable 1).

Renal Ultrasonography – Pre-surgical Assessment

In rectovaginal endometriosis, renal ultrasound is essential to rule out renal obstruction. Cervical carcinoma and endometriosis should be considered in cases of renal obstruction.

Laparoscopy is the surgical gold standard. However, robust evidence supporting specific surgical methods for endometriosis and deep infiltrating endometriosis is still limited (as is true for many surgically treated conditions). A safe laparotomy is preferable to an unsafe laparoscopy; surgical skill is a critical factor in endometriosis surgery.

eTable 1. Current Treatments of Endometriosis

| Treatment | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Surgical treatments | Peritoneal endometriosis |

| Ovarian endometriosis | |

| Deep infiltrating endometriosis | |

| Uterine adenomyosis | |

| Sterility | |

| Pharmacotherapeutic modalities | Gestagens |

| Combined oral contraceptives | |

| GnRH analogues | |

| Pain therapy | |

| Complementary approaches and initial measures | Psychosomatic therapy |

| Physiotherapy | |

| Nutrition | |

| Traditional Chinese medicine | |

| Ayurveda | |

| Homeopathy | |

| Osteopathy |

Endocrine Pharmacotherapy

Endocrine therapy is generally used as neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment after histological confirmation of endometriosis, and for recurrence management.

Potential Side Effects of Gestagens in Endometriosis Treatment

Breakthrough bleeding, weight gain, fluid retention, skin changes, hot flashes, breast tenderness, headache, vaginal dryness.

While surgery combined with pharmacotherapy is often the best approach, asymptomatic patients with stenosing ureteric endometriosis are an exception, where surgery is clearly indicated (level 1a evidence). The necessity of surgery for asymptomatic ovarian endometriomas remains unclear, as surgery can damage ovarian tissue. Asymptomatic endometriosis is rare (5-10% of cases, level 4 evidence). It is crucial to address clinical manifestations of endometriosis (eBox) while avoiding over-treatment and considering psychosomatic, social, occupational, and relationship impacts. Cyclical symptoms and pain affecting daily life necessitate timely gynecological and laparoscopic evaluation to confirm or exclude endometriosis before initiating treatment. Chronification of symptoms is a serious complication to avoid in endometriosis management.

Surgical Treatment of Bladder Endometriosis

Surgery is the primary treatment for symptomatic bladder endometriosis [10, 15]. The surgical approach (laparoscopy or laparotomy) depends on surgeon expertise [10, 14]. Innovative techniques have evolved [10, 15, 17].

Symptomatic Rectovaginal Endometriosis – Surgical Choice

Surgery is the preferred treatment for symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis.

The procedure involves dissecting the infiltrated bladder portion from the uterus or cervicoisthmic junction until disease-free vesico-uterine space is reached (eFigure 1). A partial vesical resection, whetstone or orange-slice shaped, is performed [10]. The bladder trigone and its neural structures are vulnerable during resection [10, 15]. R0 resection (complete removal) is the surgical goal. The bladder is closed with seromuscular sutures and tested for leaks with methylene blue. Postoperative transurethral drainage is recommended for six days. A neurogenic bladder is a serious complication due to vesical denervation from endometriosis or treatment, potentially requiring permanent catheterization or neurostimulator implantation. Adjuvant anti-endocrine therapy follows national guidelines for deep infiltrating endometriosis [e4]. Rehabilitation or specialized care is often needed for chronic endometriosis (level 4 evidence).

Surgical Treatment of Ureteric Endometriosis

Surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis or endometriosis-related pelvic adhesions carries a risk of ureteric complications [9], including urinoma or uroperitoneum leading to infection. Interdisciplinary collaboration is crucial for complex cases [20].

In extrinsic ureteric endometriosis, surgery aims at ureterolysis and decompression [15]. For intrinsic ureteric endometriosis, partial ureter resection with end-to-end anastomosis or ureteric reimplantation (e.g., psoas hitch) is needed [15]. Ureter freeing down to the bladder junction is often necessary for parametrial resection. Retroperitoneal nerve preservation (hypogastric, splanchnic, femoral, obturator) is vital to prevent neurogenic bladder. Ureteric stents are recommended for four to six weeks postoperatively after extensive ureteric surgery.

The Treatment of Choice – Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is the gold standard for surgical endometriosis treatment, though robust evidence for deep infiltrating endometriosis surgical methods is limited.

Surgical Treatment of Rectovaginal Endometriosis

Asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic deep infiltrating endometriosis can be managed conservatively with close monitoring (annual rectovaginal exams by an experienced gynecologist), provided there is no stenosis, hemorrhage, or progressive disease (level 2 evidence). Further diagnostics like MRI or transrectal ultrasound with rectosigmoidoscopy may be needed. Surgery is the treatment of choice for symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis [20]. Various surgical techniques aim for R0 resection (eTable 1). Regardless of approach, the infiltrated rectosigma needs mobilization from adhesions (Case Illustration Figure 4) and resection with end-to-end anastomosis. Full patient informed consent is essential [16, 19]. Specialized endometriosis centers are recommended for deep infiltrating endometriosis treatment due to potential complications and disease severity. Suture-line dehiscence and rectovaginal fistula are potential complications [22-24]. Laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation (LUNA) and other nerve ablation techniques are not widely adopted based on current evidence for pain management. Adjuvant and experimental treatments should be discussed individually with patients [25].

Case Illustration: Transvaginal Laparoscopic Anterior Resection of Rectum (TLARR) for Rectovaginal Endometriosis

A 23-year-old woman with severe abdominal pain, factor VII deficiency, and endometriosis underwent TLARR.

Case Illustration: Transvaginal Laparoscopic Anterior Resection of Rectum (TLARR) for Rectovaginal Endometriosis. (a) Mobilization of endometriosis focus from posterior fornix and rectum, vaginal closure. (b) Uterus fixation to abdominal wall for access. (c) Rectum with endometriosis freed from adhesions, myometrium separation, nerve/vessel preservation. (d) Focus separation with linear stapler. (e-h) Descending colon mobilization, rectum pulled in front of vagina, focus resection, oral stump preparation, stapler head introduction, vaginal closure, laparoscopic anastomosis via transanal approach, functionality testing.

Endocrine Treatment for Endometriosis

Endocrine therapy is used adjuvant to surgery, neoadjuvant (less favored due to tissue plane effects), and for recurrence. For extensive and deep infiltrating endometriosis, R0 resection is often unattainable, making adjuvant endocrine therapy to induce therapeutic amenorrhea valuable. Options include:

- Gestagens

- Oral contraceptives

- GnRH analogues

- Pain therapy

- Combinations

- Experimental treatments

Options for Pharmacotherapy

- Gestagens

- Oral contraceptive drugs

- GnRH analogues

- Analgesics

Gestagens in Endometriosis Treatment

Gestagens induce secretory transformation in estrogen-primed endometrium (Tables 1 & 2).

Table 1. Efficacy Spectrum of Gestagens in Endometriosis Treatment

| Gestagen | Partial effects |

|---|---|

| Gestagenic effect | |

| Progesterone derivatives | |

| Progesterone | + |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | + |

| Megestrol acetate | + |

| Chlormadinone acetate | + |

| Cyproterone acetate | + |

| Drospirenone | + |

| Dydrogesterone | + |

| Nortestosterone derivatives | |

| Norethisterone | + |

| Norethisterone acetate | + |

| Ethynodiol diacetate | + |

| Lynestrenol | + |

| Levonorgestrel | + |

| Desogestrel | + |

| Gestodene | + |

| Norgestimate | + |

| Dienogest | + |

Table 1: Efficacy spectrum of gestagens in endometriosis treatment. Dienogest (2mg) approved in Europe for endometriosis, alongside GnRH analogues.

Table 2. Endocrine Pharmacotherapy Recommendations for Endometriosis

| Substance | Dosage |

|---|---|

| GnRH analogues (selected) | |

| Leuporelin acetate | 3.75 mg / 4 weeks SC |

| Leuporelin acetate | Three-month depot SC |

| Goserelin acetate | 3.8 mg / 4 weeks SC |

| Buserelin acetate | 3–4 × 300 μg/d |

| Nafarelin acetate | 2–4 × 460 μg/d |

| Triptorelin acetate | 105 μg/d |

| Parenteral gestagen preparataions (selected) | |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | 150 or 104 mg IM every 12 weeks |

| Etonogestrel | 68 mg SC implant for up to three years |

| Norelgestromin | One patch per week |

| Gestagen-containing intrauterine devices | |

| Levonorgestrel | 20 μg / 24 h |

| Progesterone derivatives (selected) | |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) | 30–50 mg/d |

| Medrogestone | 50–75 mg/d |

| Nortestosterone derivatives (selected) | |

| Lynestrenol | 10 mg/d |

| Desogestrel | 0.075–0.15 mg (= 1–2 Tabl/d) |

| Dienogest*2 | 2 mg/d |

| Combined oral contraceptives (selected) | |

| Second-generation preparations | |

| Levonorgestrel | 100 µg + 20 µg EE |

| Levonorgestrel | 150 µg + 30 µg EE |

| Levonorgestrel | 250 µg + 30 µg EE |

| Norethisterone | 0.5 mg + 20 µg EE |

| Norethisterone acetate | 0.5 mg + 30 µg EE |

| Norethisterone acetate | 1.5 mg + 30 µg EE |

| Third-generation preparations | |

| Dienogest *2 | 2 mg + 30 µg EE |

| Norgestimate | 250 µg + 35 µg EE |

| Gestodene | 0.750 µg + 30 µg EE |

| Desogestrel | 150 µg + 20 µg EE |

| Desogestrel | 150 µg + 30 µg EE |

| Chlormadinone acetate | 2 mg + 30 µg EE |

Table 2: Recommendations for endocrine pharmacotherapy of endometriosis. Includes GnRH analogues, gestagens, and oral contraceptives. Dienogest is also categorized as a progesterone derivative.

Gestagen side effects include:

- Breakthrough bleeding (40-80%)

- Weight gain, fluid retention (40-50%)

- Acne, skin changes (20%)

- Hot flashes, libido loss (>30%)

- Breast tenderness (10%)

- Headache (10%)

- Vaginal dryness, transient alopecia, osteopenia, mood swings (10%)

Metabolic effects:

- Atherogenic indices (↑LDL, ↓HDL)

- Carbohydrate metabolism (↓glucose tolerance, ↑insulin resistance)

Increased venous thromboembolism risk, mild natriuretic effect, cervical secretion alteration, and vaginal candidiasis are also noted.

Oral Contraceptives for Endometriosis

Oral contraceptives (off-label use) induce a pseudopregnancy state (Table 2, eTable 1). Side effects vary by preparation but include breakthrough bleeding, nausea, headache, increased venous thromboembolism risk, libido loss, cutaneous reactions, sodium/fluid retention, weight gain, breast tenderness, and blood pressure rise. Generally, they are well-tolerated.

Treatment goal is therapeutic amenorrhea. Breakthrough bleeding can be managed by doubling the daily dose temporarily, then returning to a single tablet. Patient education is crucial.

GnRH Analogues in Endometriosis Treatment

GnRH analogues cause a “functional oophorectomy,” inducing hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (Table 2, eTable 1). Side effects include:

Women with Endometriosis and Fertility Desires

Hormonal drugs are not recommended for women desiring pregnancy as they do not improve fertility.

- Hot flashes and perspiration (80-90%)

- Sleep disturbance (60-90%)

- Vaginal dryness (30%)

- Headache (20-30%)

- Mood changes (depressive mood, >10%)

- Osteopenia, libido loss (>30%)

- Weight gain (ca. 15%).

Combined Treatment Approaches: Pharmacotherapy and Pain Management

Complementary treatments without strong scientific evidence can be used alongside surgery and pharmacotherapy. Women with impaired quality of life due to pain seek pain-free status, improved quality of life, and productivity (eTable 2). Specialized endometriosis centers offer team-based care involving gynecologists, surgeons, pain specialists, psychotherapists, and patient participation. Untreated pain can lead to job loss or relationship breakdown.

eTable 2. NSAIDs and Co-analgesics for Endometriosis-Related Pain

| Substance | Recommended dose | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Diclofenac | 50–150 mg/d (2–3 ×/d) or 100 mg sustained release/d | GI ulcer risk, ulcer prophylaxis recommended. |

| Ibuprofen | 200–2400 mg/d (3–4 ×/d) or Ibuprofen 800 mg sustained release (max. 3 x 800 mg/d) | Insomnia, asthma, alopecia, psychotic reactions, edema, abuse potential. |

| Naproxen | 500–1000 mg/d (2–4 ×/d) | |

| Metamizole sodium | 8–16 mg per kg body weight, up to 4 ×/d | |

| Etoricoxib | 1 × 90–1 × 120 mg/d | Edema, diarrhea, dizziness, rare arrhythmia, cardiovascular events. Off-label use for endometriosis pain. |

| Celecoxib | 2 × 200–400 mg/d | Similar to etoricoxib. Off-label use. |

| Coanlagesics and opioids | ||

| Amitriptyline | 12.5–75 mg/d (evening) | Improves sleep, cholinergic side effects, ECG, blood counts, transaminases monitoring, slow titration. |

| Nortriptyline | Cf. amitriptyline | Fewer sedative effects than amitriptyline. |

| Gabapentin | 1800–3600 mg/d (3 doses) | Well-tolerated anticonvulsant, slow titration. Alternative: pregabalin. |

| Tramadol | Individual titration; 100–200 mg sustained release (2 ×/d) | Weak opioid, non-narcotic, additional non-opioid analgesia. |

| Tilidine/naloxone | Individual titration; 2 × 100 to 3 × 200 mg sustained release/d | Weak opioid, non-narcotic, opioid antagonist (overdose protection). |

| Morphine sulfate | Individual titration | Sedation, dizziness, respiratory depression, constipation, drug interactions, monitor for adverse effects. |

| Fentanyl | Individual titration | Transdermal patch, long-term use only. |

Experimental Treatment Approaches for Endometriosis

Endometriosis cells share properties with malignant tumors: invasiveness, migration, metastasis, angiogenesis, neurogenesis. Cytokines, TNF-α, COX-2, oxytocin, and aromatase responsiveness are targeted for new diagnostic and therapeutic methods [3, 4, 13, 25]. Aromatase inhibitors combined with gestagens or GnRH analogues show effectiveness, but side effects and cost limit practicality [4].

Experimental Approaches in Endometriosis

Cytokines, tumor necrosis factor, cyclooxygenases, oxytocin, and aromatases are targets for novel endometriosis diagnosis and treatment strategies.

Overview and Conclusion

Therapeutic nihilism for extensive endometriosis is not justified. Germany is at the forefront of endometriosis care, with quality patient care, research infrastructure, physician training, CME, and certified endometriosis centers, supported by organizations like the German Foundation for Endometriosis Research (SEF), European Endometriosis League (EEL), and German Endometriosis Association.

Complementary Treatment Approaches

These can supplement pharmacotherapy and surgery, as discussed, for a holistic patient management.

Further Information on CME

[Section on CME information from original article – retain if relevant for target audience, otherwise can be omitted in a general guide].

eFigure 1. Endometriosis with Transmural Bladder Infiltration

eFigure 1: Endometriosis with transmural bladder infiltration. (a) “V for victory” sign in bladder endometriosis with round ligament involvement. (b) TUR ineffectiveness due to outward-to-inward growth. (c-d) Whetstone-shaped resection of bladder roof endometriosis. (e-f) Laparoscopic bladder wall closure.

Acknowledgments

[Keep acknowledgements from original article if desired].

Footnotes

[Keep footnotes from original article if desired].

References

[Use references from original article, ensuring proper formatting].