Early and accurate cancer diagnosis is critical for improving patient outcomes. However, delays in diagnosis, particularly within primary care settings, remain a significant concern. This article delves into the factors contributing to Delayed Diagnosis Of Cancer In Primary Care, drawing upon a comprehensive systematic review of existing literature. Understanding these factors is crucial for developing strategies to improve diagnostic pathways and ultimately enhance patient care.

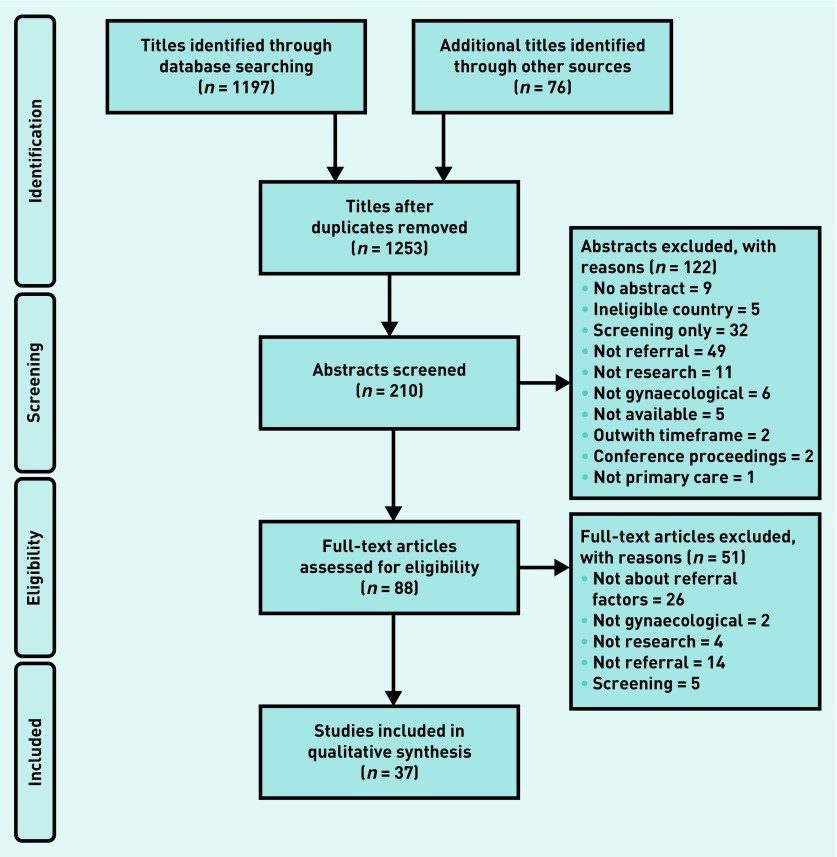

The systematic review process, outlined in the PRISMA diagram below, involved a thorough search and analysis of relevant studies to identify key themes and subthemes related to diagnostic delays. Initial searches yielded 1253 titles, which were narrowed down through abstract and full-text screening to a final set of 37 articles that met the rigorous inclusion criteria. These studies employed diverse methodologies, including cohort studies, retrospective reviews, questionnaires, qualitative research, and surveys, providing a multifaceted perspective on the issue of delayed cancer diagnosis.

PRISMA Flow Diagram Illustrating the Study Selection Process for a Systematic Review on Delayed Diagnosis of Cancer in Primary Care. This diagram details the stages of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of studies, outlining the number of articles at each step and reasons for exclusion.

PRISMA Flow Diagram Illustrating the Study Selection Process for a Systematic Review on Delayed Diagnosis of Cancer in Primary Care. This diagram details the stages of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of studies, outlining the number of articles at each step and reasons for exclusion.

The analysis of the collected data revealed three overarching themes mirroring the diagnostic intervals defined in the Aarhus statement: patient factors, doctor factors, and system factors. Each of these broad themes encompasses several subthemes that further elucidate the complexities of diagnostic delay in primary care.

Patient Factors Contributing to Delayed Diagnosis

Patient-related factors play a significant role in the timeline of cancer diagnosis. These factors can range from demographic characteristics to symptom perception and health-seeking behaviors.

Patient Demographics and Socioeconomic Status

Interestingly, several studies within the review indicated that socioeconomic status (SES) may not directly influence the diagnostic journey in all contexts. However, nuances emerge when examining specific cancer types and healthcare systems. For instance, while some research found no association between SES and diagnostic delay in general, one study highlighted delays in endometrial cancer diagnosis among patients with lower SES.

In healthcare systems where insurance and payment models are prevalent, lower income was demonstrably linked to both diagnostic and treatment delays. Furthermore, research from Denmark suggested that women of higher SES exhibited a greater capacity for ‘seeking and sustaining treatment,’ indicating proactive health-seeking behaviors. This is reinforced by findings that women of higher SES are generally more likely to expedite their engagement with healthcare services.

The impact of SES extends beyond diagnostic timelines, influencing survival rates as well. Studies in Denmark revealed a correlation between SES and cancer mortality, with endometrial and ovarian cancer mortality being highest among women with lower educational attainment. Conversely, cervical cancer survival was highest in those with higher SES. While some studies found no direct effect of education on delay, others indicated decreased delay in individuals with higher educational attainment, and an association between lower survival and lower attainment. Notably, women with higher education are also more likely to be referred to specialists by their primary care physicians, suggesting a potentially smoother and faster diagnostic pathway. A pooled analysis of multiple studies further underscored the link between lower educational attainment and an increased risk of being diagnosed with advanced-stage ovarian cancer.

Ethnicity and Cultural Factors

The role of ethnicity in diagnostic delay presented a mixed picture in the reviewed literature. One study in the UK indicated that Black or ethnic minority women were more likely to require multiple GP visits before referral, potentially suggesting barriers in initial access or communication. However, other studies found no direct correlation between ethnicity and diagnostic delay.

Despite the ambiguity regarding diagnostic delay, poorer survival rates were observed in Black and Latino women in the US, and Pacific and Maori women in New Zealand. This disparity suggests that factors beyond the initial diagnostic interval, such as cultural attitudes towards health, access to follow-up care, or treatment disparities, may significantly influence cancer outcomes in these populations. Cultural beliefs and healthcare system navigation complexities could contribute to differences in presentation, adherence to treatment, and overall survival.

Age and Life Stage

Age emerged as a significant factor in several studies, particularly in the UK, Sweden, and Denmark. Counterintuitively, some studies found that older females (≥75 years), housebound individuals, and retirees were more likely to present earlier. Conversely, working-age females were more prone to delay presentation, although other research found age to be an insignificant factor. Interestingly, patients diagnosed with ovarian cancer aged ≤55 years were more likely to have had multiple consultations before referral, indicating potential diagnostic challenges in younger women.

When examining urgent referrals, older patients were more likely to receive an earlier diagnosis compared to younger patients. However, in the specific context of endometrial cancer, older patients were more frequently diagnosed with late-stage disease, highlighting the complexity of age as a factor and the potential for age-related biases in diagnostic processes.

Rurality and Geographic Access

Geographic factors, specifically rurality and distance from healthcare facilities, consistently emerged as contributors to diagnostic delay. Studies demonstrated that patients residing in rural areas or further from healthcare centers experienced increased delays. This is likely due to a combination of factors, including reduced access to primary care physicians, longer travel times to specialists, and potentially limited awareness of cancer symptoms in geographically isolated communities.

Symptoms and Symptom Knowledge

A critical patient-related factor is the understanding and interpretation of cancer symptoms. Research consistently showed a lack of symptom knowledge regarding ovarian, cervical, and endometrial cancers among patients. This lack of awareness can lead to delayed recognition of symptoms as potentially serious and consequently, delayed presentation to primary care.

The nature of symptoms also plays a crucial role. Abnormal vaginal bleeding, a more specific and often alarming symptom, was associated with less delay compared to vague or gastrointestinal symptoms. Patient delay was found to be more pronounced in cervical cancer compared to endometrial cancer, likely because bleeding in premenopausal women is less frequently perceived as a symptom of serious illness. Women may attribute abnormal bleeding to menstrual irregularities or other benign causes, delaying their consultation with a healthcare provider.

Furthermore, patients may experience ‘bodily sensations’ like abdominal distension or pain, but organizational, cultural, and social factors heavily influence whether these sensations are interpreted as symptoms requiring medical attention. Many women may normalize such sensations, attributing them to menopause or non-gynecological causes, thus delaying health-seeking behavior.

Presentation to Primary Care and Health-Seeking Behavior

Timely presentation to primary care is paramount for early diagnosis. Studies indicated that women who undergo regular cancer screening experienced less diagnostic delay. Conversely, consulting with multiple GPs before diagnosis was linked to later disease stages, potentially reflecting a longer and more complex diagnostic journey.

The International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership highlighted significant differences in cancer awareness and beliefs across countries, impacting presentation behaviors. The UK was found to have the ‘highest mean barriers to symptomatic presentation,’ including embarrassment and worry about potential diagnoses, compared to other high-income countries. These barriers can contribute to significant patient delay in seeking medical attention even when symptoms are present.

Doctor Factors in Delayed Diagnosis

Physician-related factors are equally critical in understanding diagnostic delays. These factors encompass GP demographics, symptom interpretation, and referral practices.

Doctor Demographics and Patient Socioeconomic Status

Similar to patient-level observations, some studies suggested that GPs in Denmark were less likely to delay referrals for women with higher SES. Systematic reviews also indicated that lower patient educational status was associated with referral delays initiated by doctors. This raises concerns about potential unconscious biases or systemic factors within primary care settings that might inadvertently contribute to disparities in access to timely diagnosis.

Age also appears to influence physician behavior. Several articles found that increasing patient age was associated with increased referral delay by GPs. However, contrasting findings indicated that delay was greater if the patient was younger, potentially linked to menstrual status and the perception of risk in younger women. Marital status, however, was not found to affect referral delay, suggesting it is not a significant factor in physician decision-making in this context. Rurality, on the other hand, was associated with referral delay in one study, possibly reflecting resource limitations or access to specialist services in rural areas.

Symptom Interpretation and Clinical Decision-Making

The nature of symptoms presented significantly impacts physician response and diagnostic timelines. Non-specific, atypical, and gastrointestinal symptoms were consistently linked to increased delays. Failure by physicians to recognize the significance of certain symptoms, particularly postcoital bleeding, led to longer delays in cervical cancer diagnosis. Conversely, older women with postmenopausal bleeding experienced shorter delays, likely due to the higher index of suspicion for cancer in this population.

Research exploring ‘suboptimal clinical decisions’ revealed that endometrial cancer was less likely to involve such decisions compared to ovarian cancer and cases presenting with non-alarm symptoms. This suggests that diagnostic pathways for endometrial cancer, often characterized by more specific symptoms like postmenopausal bleeding, may be more streamlined. Non-investigation of symptoms, including postmenopausal bleeding, was directly associated with increased diagnostic delay. Critically, failing to even consider cancer as a possible diagnosis is a fundamental factor leading to diagnostic delays.

Misdiagnosis, whether through treating patients symptomatically without further investigation or attributing symptoms to other conditions, is a significant contributor to both referral and diagnostic delay. Comorbidities can further complicate diagnostic processes and contribute to delays, potentially by diverting clinical attention or masking cancer symptoms.

Referral Process and Communication

Inefficiencies and inadequacies within the referral process itself are major sources of delay. Failure to refer patients to gynecology specialists, non-urgent referrals when urgency is warranted, and referrals made without explicitly stating a suspicion of cancer were all associated with diagnostic delays.

In cases involving multiple consultations before referral, a lack of follow-up was frequently observed, leading to delays. Poor communication can also hinder patient re-presentation with persistent symptoms or impede effective follow-up. Furthermore, inadequate communication can impair a GP’s ability to formulate an accurate differential diagnosis, contributing to delays. False-negative results from initial investigations ordered by GPs can also lead to significant diagnostic delays.

The role of pelvic examinations in primary care was investigated, with conflicting findings. While one study found no association between pelvic exams and diagnostic delay, others demonstrated delays when pelvic exams were not performed. Misinterpreting abnormal findings as normal during pelvic examinations also contributed to delays.

The implementation and effectiveness of clinical guidelines, such as USCR guidelines, were examined. One study showed no survival difference in ovarian cancer patients based on USCR guideline use. However, other research indicated that failure to meet urgent referral criteria could lead to delay, and that guidelines were not consistently applied in cervical cancer diagnoses. Paradoxically, further study of USCR guidelines showed that their use was associated with increased median diagnostic intervals for cervical and endometrial cancers, although referrals using NICE symptom guidelines demonstrated decreased diagnostic intervals. This complexity suggests potential issues with specific guideline implementation or interpretation. Ovarian cancer diagnosis was found to be quicker with USCR referrals, regardless of the specialty referred to, compared to routine referrals.

The interface between primary and secondary care is also a critical point for potential delays. The need for senior clinicians to screen referrals and delays arising from slow communication of test results between primary and secondary care settings were highlighted. Furthermore, waiting times for secondary care appointments themselves contribute to overall diagnostic delay.

System Factors Influencing Diagnostic Timelines

System-level factors, encompassing healthcare organization and resource allocation, also play a crucial role in shaping diagnostic timelines.

Shorter system delays were observed in wealthier females and patients seen by GPs who did not routinely manage their care, potentially suggesting differences in referral pathways or resource allocation for different patient groups. Patients described as ‘less compliant’ and those with high alcohol intake experienced greater system delays, as did patients referred by female GPs, raising questions about potential biases or systemic issues within the healthcare system.

The gatekeeper role of GPs in healthcare systems has been suggested as a potential source of diagnostic delay. Limited access to investigations, both actual and perceived, was consistently identified as a system-level barrier contributing to delays. This includes delays in obtaining necessary imaging, biopsies, or specialist consultations due to resource constraints, bureaucratic processes, or geographical limitations.

Conclusion

Delayed diagnosis of cancer in primary care is a multifaceted problem stemming from a complex interplay of patient, doctor, and system-level factors. Addressing this issue requires a comprehensive approach that considers each of these domains. Improving patient awareness of cancer symptoms, enhancing communication between patients and physicians, optimizing referral pathways, ensuring timely access to investigations, and mitigating potential biases within the healthcare system are all essential steps. Further research is needed to develop and implement targeted interventions to reduce diagnostic delays and ultimately improve outcomes for individuals affected by cancer. By focusing on these key areas, healthcare systems can strive to achieve earlier and more accurate cancer diagnoses in primary care, leading to more effective treatments and improved patient survival.