Early and accurate diagnosis is paramount in managing dementia. A comprehensive evaluation is essential, incorporating a detailed medical history, thorough physical and neurological examinations, cognitive and behavioral assessments, activities of daily living evaluation, laboratory investigations, and neuroimaging studies. This detailed approach is crucial for differentiating dementia from other conditions and identifying the specific underlying cause.

Dementia, increasingly prevalent with the aging global population, represents a significant healthcare challenge. Characterized by a gradual and progressive decline in cognitive functions, dementia also manifests in personality and behavioral changes, and a decline in the ability to perform daily activities. The insidious onset of symptoms can be challenging to discern, as some manifestations may overlap with normal aging. The symptom complex evolves over months to years, highlighting the importance of early recognition to implement comprehensive therapeutic strategies, including pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, psychosocial support, and guidance for legal and financial planning. Addressing the misconception in some communities that dementia is an inevitable part of aging is crucial, necessitating culturally sensitive educational programs to promote timely diagnosis and intervention.

The economic impact of dementia diagnosis and treatment is substantial, affecting healthcare systems and families alike. Patients may be forced to leave employment or retire early, while family caregivers often reduce their work hours, facing increased emotional and physical strain due to the prolonged nature of many dementias. Healthcare costs escalate further when cognitive decline and behavioral symptoms complicate medical conditions, frequently requiring specialized tests, referrals, and expensive medications.

Etiology and Differential Diagnosis of Dementia: A Broad Spectrum

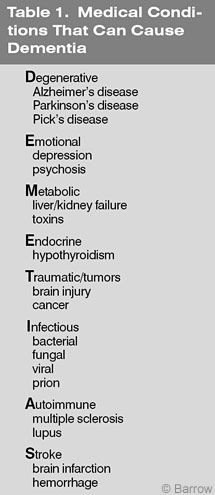

A wide range of systemic and neurological disorders can present with signs and symptoms mimicking dementia. The differential diagnosis is extensive, encompassing degenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and Pick’s disease, as well as emotional disorders like depression, metabolic imbalances from organ failure, neoplastic conditions such as carcinomatous meningitis, traumatic brain injury (TBI), immunological disorders like multiple sclerosis, infectious diseases such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, endocrine disorders like hypothyroidism, nutritional deficiencies such as vitamin B12 deficiency, and cerebrovascular diseases.

Diagnosis becomes particularly complex as the majority of dementia cases occur in middle-aged and older individuals who are also susceptible to systemic and neurological comorbidities. Polypharmacy is common in this population, increasing the risk of drug-related adverse events that can mimic or exacerbate neuropsychiatric symptoms. For example, extrapyramidal symptoms from chronic neuroleptic use could be misdiagnosed as PD with dementia or AD with Lewy bodies.

Degenerative central nervous system (CNS) disorders are the most prevalent cause of dementia. It’s important to remember that neurodegeneration is a protracted process, developing over months or years before clinical symptoms become apparent. Even with early detection, the pathological process likely began much earlier, progressing insidiously and bilaterally, although initial neurological signs may be asymmetrical. As the disease advances, it can become diffuse or multifocal due to transsynaptic degeneration. While risk factors are identified for some conditions, many neurodegenerative dementias are idiopathic.

Presenting symptoms may be triggered or exacerbated by emotional or physical trauma, or exposure to certain medications, particularly those with anticholinergic properties, which can worsen cholinergic deficiency in AD. For instance, some patients have developed progressive dementia after using anticholinergic eye drops. Bereavement can precipitate depression, memory loss, and language difficulties, while surgery and general anesthesia may lead to persistent agitation, confusion, hallucinations, and memory impairment. Neurobehavioral testing before surgery may be prudent for vulnerable patients undergoing general anesthesia.

AD is the most common neurodegenerative disorder, accounting for at least 65% of dementia cases in middle-aged and older adults. Vascular dementia, secondary to cerebrovascular disease, accounts for 10 to 15% of cases. However, neuropathological studies indicate that AD and vascular dementia lesions coexist in 30 to 35% of cases. PD, the third leading cause of dementia, is accompanied by cognitive impairment in at least 30% of cases.

Multiple factors can contribute to dementia in PD. Classic PD with dementia is characterized by deficits in executive function, linked to degeneration of prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia connections. Basal ganglia strokes, coexisting AD, and Lewy body dementia can also contribute to cognitive decline in PD and Parkinsonian syndromes with cognitive deficits. Less common etiologies include frontotemporal dementias like Pick’s disease, Lewy body dementia, Parkinsonian syndromes such as progressive supranuclear palsy, prion diseases, infections, neurotoxins, neoplasms, paraneoplastic syndromes, TBI, and metabolic, immunologic, nutritional, and endocrine disorders. Low vitamin B12 levels are a frequent finding in cognitively impaired patients, often due to altered eating habits rather than pernicious anemia. Vitamin B12 supplementation is indicated to correct deficiency and ensure adequate levels.

Other conditions to differentiate from dementia include delirium or encephalopathy, intellectual disability, language disorders, and pseudodementia. Delirium is typically an acute condition caused by toxic-metabolic disturbances, characterized by fluctuating consciousness and mental status. Prompt identification and treatment of the underlying cause can reverse neuropsychiatric symptoms, while delayed management can lead to permanent brain damage. Individuals with intellectual disability may be misdiagnosed with dementia due to inherent cognitive and adaptive deficits. Neuropsychological testing is crucial to document higher cortical dysfunction and guide appropriate educational programs. Aphasias and language disorders can be mistaken for dementia if lateralizing neurological signs are absent. However, most cases involve focal or multifocal intracranial lesions detectable with CT and MRI.

Pseudodementia often refers to cognitive symptoms arising from depression, psychosis, or a history of substance abuse. Diagnosing these conditions can be challenging as dementia can also manifest with personality and behavioral changes preceding cognitive decline. Pseudodementia can mimic dementia symptoms. The absence of focal neurological abnormalities and a thorough neuropsychiatric history and assessment, including neuropsychological and psychiatric evaluations, are crucial for accurate diagnosis.

Dementia Differential Diagnosis Table

To aid in the differential diagnosis of dementia, the following table summarizes key differentiating features of various dementia types and related conditions:

| Condition | Etiology | Onset & Progression | Key Cognitive Symptoms | Other Neurological/Physical Signs | Diagnostic Clues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) | Neurodegenerative (plaques & tangles) | Insidious, gradual progression | Memory loss (early prominent), visuospatial deficits, language difficulties | None initially, later motor slowing, rigidity possible | Family history, biomarker evidence (CSF, PET), atrophy on MRI |

| Vascular Dementia (VaD) | Cerebrovascular disease (strokes, ischemia) | Stepwise or sudden onset, variable progression | Executive dysfunction, slowed processing speed, memory impairment (variable) | Focal neurological deficits (weakness, sensory loss), gait disturbance, dysarthria | History of stroke/vascular risk factors, focal lesions on neuroimaging (CT/MRI) |

| Lewy Body Dementia (LBD) | Lewy body deposition | Fluctuating, progressive | Fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, attention deficits, executive dysfunction | Parkinsonism (rigidity, bradykinesia), REM sleep behavior disorder | Fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, parkinsonism not explained by PD, DaTscan |

| Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) | Frontal and/or temporal lobe degeneration | Insidious, gradual progression | Behavioral changes (disinhibition, apathy), language deficits (aphasia), executive dysfunction | Motor neuron disease (in some variants), primitive reflexes | Prominent behavioral or language changes early, frontal/temporal atrophy on neuroimaging |

| Parkinson’s Disease Dementia (PDD) | Lewy body pathology in PD | Develops years after PD diagnosis | Executive dysfunction, attention deficits, visuospatial deficits, memory impairment (later) | Parkinsonian motor symptoms (tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia) precede dementia | Dementia onset > 1 year after PD diagnosis, Parkinsonian features prominent |

| Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH) | CSF circulation impairment | Gradual, progressive | Cognitive impairment (executive dysfunction, slowed processing) | Gait disturbance (magnetic gait), urinary incontinence | Ventriculomegaly on neuroimaging, improvement after CSF tap/shunt |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) | Prion disease | Rapidly progressive | Rapid cognitive decline, myoclonus, cerebellar signs, visual disturbances | Myoclonus, ataxia, pyramidal signs | Rapid progression, EEG (periodic sharp wave complexes), CSF 14-3-3 protein, MRI (DWI) |

| Depression (Pseudodementia) | Psychiatric disorder | Variable, can be rapid or gradual | Cognitive complaints, poor effort on testing, memory and concentration difficulties | Symptoms of depression (sadness, anhedonia, sleep disturbance), no focal neurological signs | History of depression, mood symptoms prominent, cognitive deficits improve with antidepressant treatment |

| Delirium | Toxic-metabolic, infection, medication side effects | Acute onset, fluctuating | Disturbed consciousness, attention deficits, disorganized thinking, fluctuating cognition | Underlying medical illness, autonomic instability, agitation/lethargy | Acute onset, fluctuating course, identifiable underlying cause, resolves with treatment of cause |

Dementia Etiologies and Differential Diagnoses Table

Dementia Etiologies and Differential Diagnoses Table

Figure 1: Differential Diagnosis of Dementia. This table summarizes various conditions that can cause dementia, highlighting key features for differential diagnosis.

Diagnostic Approach to Dementia

Diagnosing dementia necessitates a structured approach:

-

Comprehensive History: A detailed medical history is crucial. Often, patients themselves may not provide reliable information, making caregivers essential informants. Information should include symptom onset, evolution, duration, exacerbating and relieving factors, comorbidities, medications, travel history, occupational exposures, family history, and history of sexually transmitted infections. Changes noticed by family and friends, such as declining work performance, accidents, financial mismanagement, loss of interest in hobbies, repetitive questioning, and personality changes, can be significant indicators. Word-finding difficulties and progressive aphasia, sometimes attributed to strokes, may be early signs of AD or primary progressive aphasia. Family history, particularly early-onset dementia, may suggest familial AD, while late-onset dementia may be associated with Apo-E 4 genotype.

-

Physical and Neurological Examinations: A thorough physical and neurological examination is essential to identify systemic diseases and focal or multifocal neurological deficits. Signs like uncontrolled hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, valvular heart disease, carotid bruits, and peripheral arterial disease, along with stepwise dementia progression and focal signs, suggest vascular dementia. Temporal tenderness, muscle aches, joint pains, and abnormal pulses may indicate vasculitis. Cranial bruising may indicate TBI.

The neurological examination should assess activities of daily living, cognition, and behavior. Parkinsonian signs (tremor, masked facies, bradykinesia, rigidity, gait disturbance) combined with visual hallucinations and mood fluctuations are suggestive of LBD. In contrast, PD patients developing dementia may have PDD, PD with AD, or PD with vascular disease. Parkinsonism with falls, abnormal eye movements, rigidity, and cognitive impairment may suggest progressive supranuclear palsy. Increased reflexes and sensory deficits can be associated with vitamin B12 deficiency. Myoclonic jerks and ataxia are red flags for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Asymmetrical weakness, pathological reflexes, and sensory changes indicate structural lesions. Frontal lobe release signs can be seen in neurodegenerative disorders.

-

Cognitive and Behavioral Testing: Standardized tests are essential to evaluate cognition, behavior, and activities of daily living. Tools like the Mini-Mental State Examination, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale, Dementia Rating Scale, Geriatric Depression Scale, Neuropsychiatric Inventory, and Progressive Deterioration Scale help quantify impairments, determine disease stage, and guide management. Formal neuropsychological assessment can further define cognitive, behavioral, personality, language, and motoric functions. Serial neuropsychological testing is valuable in early or atypical cases to track subtle changes.

-

Laboratory and Neuroimaging Studies: Diagnostic tests are necessary to identify treatable conditions and exclude reversible causes of cognitive impairment. Routine tests include complete blood count, sedimentation rate, metabolic profile, thyroid function tests, VDRL, serum B12, folate, homocystine levels, urinalysis, and non-contrast brain CT or MRI. Contrast imaging is indicated if intracranial mass lesions are suspected. MRI can also assess for cerebrovascular disease. PET scans may help differentiate AD from frontotemporal dementia in atypical cases. EEG is useful for suspected epilepsy, Herpes simplex encephalitis, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. CSF studies are important for suspected CNS infections and prion diseases, with elevated CSF 14-3-3 protein supporting CJD diagnosis. PCR, smears, and cultures can detect viral and bacterial antigens/antibodies. Urine heavy metal levels are relevant in cases of neurotoxin exposure. HIV and related tests are indicated in appropriate clinical settings.

Societal Issues and Conclusion

Early and accurate dementia diagnosis, while crucial, involves comprehensive and costly medical and neurological evaluations. As diagnostic tools and therapeutic modalities advance, the economic burden of dementia care will continue to rise. A dementia diagnosis can significantly impact a patient’s life, potentially leading to loss of career, financial independence, legal rights, and social roles.

In conclusion, dementia is a complex symptom complex requiring thorough medical and neurobehavioral assessment. Early and accurate diagnosis and etiological identification are essential to provide individuals with the most appropriate and timely therapy and support. The Dementia Differential Diagnosis Table and the outlined diagnostic approach serve as valuable tools for healthcare professionals in navigating this challenging clinical landscape.

References

- Fuchs GA, Gemende I, Herting B, et al: Dementia in idiopathic Parkinson’s syndrome. J Neurol 251 Suppl 6:VI/28-VI/32, 2004

- Helpern JA, Jensen J, Lee SP, et al: Quantitative MRI assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci 24:45-48, 2004

- Johnson RT: Prion diseases. Lancet Neurol 4:635-642, 2005

- Mendez HA: Comment on The APOE-epsilon4 allele and Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics by Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K et al. JAMA 279(10):751-755, 1998. JAMA 280:1663, 1998

- Pokorski RJ: Differentiating age-related memory loss from early dementia. J Insur Med 34:100-113, 2002

- Reyes PF, Dwyer BA, Schwartzman RJ, et al: Mental status changes induced by eye drops in dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 50:113-115, 1987

- Roman GC, Royall DR: A diagnostic dilemma: Is “Alzheimer’s dementia” Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, or both? Lancet Neurol 3:141, 2004

- Silverberg GD, Mayo M, Saul T, et al: Alzheimer’s disease, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, and senescent changes in CSF circulatory physiology: A hypothesis. Lancet Neurol 2:506-511, 2003

- Swartz RH, Black SE, Sela G, et al: Cognitive impairment in dementia: Correlations with atrophy and cerebrovascular disease quantified by magnetic resonance imaging. Brain Cogn 49:228-232, 2002

- Wolters M, Strohle A, Hahn A: Cobalamin: A critical vitamin in the elderly. Prev Med 39:1256-1266, 2004