Dental hygiene diagnosis (DHDx) is a cornerstone of modern dental practice. Moving beyond simply identifying oral diseases, DHDx empowers dental hygienists to critically assess patient conditions, communicate effectively, and develop tailored care plans. This article delves into the essential components of dental hygiene diagnosis, providing clear Dental Hygiene Diagnosis Statements Examples to enhance your clinical practice and patient outcomes.

Understanding Dental Hygiene Diagnosis in Contemporary Practice

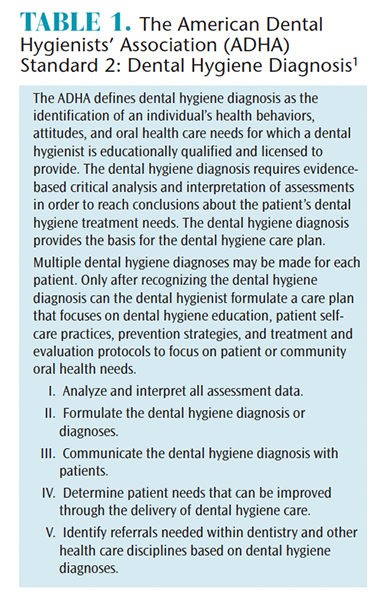

The field of dental hygiene is constantly evolving. The American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) has updated its standards to reflect the expanded role of dental hygienists in diagnosis. This shift is further underscored by the US Office of Management and Budget’s reclassification of dental hygienists as “Healthcare Diagnosing or Treating Practitioners,” placing them alongside dentists, physicians, and other diagnosticians. This recognition highlights the critical thinking and diagnostic skills inherent in dental hygiene practice.

Why is this evolution important? Research indicates that teaching and implementing DHDx leads to significant benefits:

- Enhanced Patient Communication: Clear diagnoses improve patient understanding of their oral health needs and the importance of recommended treatments.

- Individualized Care Planning: DHDx facilitates the development of comprehensive care plans tailored to each patient’s unique situation.

- Improved Informed Consent: Patients can provide truly informed consent when they understand their diagnoses and the rationale behind treatment recommendations.

- Boosted Critical Thinking: The diagnostic process strengthens the critical thinking abilities of dental hygienists.

Despite these advancements, confusion persists in clinical settings. This confusion can stem from varied classification systems for periodontal diseases, limiting DHDx to periodontal conditions only, or even debates about who is authorized to diagnose. However, the reality is that dental hygienists are uniquely positioned to provide comprehensive, patient-centered care through effective diagnosis and treatment planning.

What Constitutes a Dental Hygiene Diagnosis?

A dental hygiene diagnosis is more than just labeling a disease. It’s a clinical judgment made by a dental hygienist about an individual’s oral health conditions, needs, and well-being based on assessment data. It identifies actual or potential human responses to oral health problems that dental hygienists are educated and licensed to treat or refer.

Key components of DHDx, as outlined by professional standards, include:

- Assessment Findings: DHDx is directly linked to thorough patient assessments, including health history, clinical examinations, and risk assessments.

- Problem Identification: It clearly identifies existing or potential oral health problems that fall within the dental hygiene scope of practice.

- Etiology (Contributing Factors): Whenever possible, DHDx considers the contributing factors or etiology of the identified problems.

- Care Planning Link: DHDx serves as the foundation for developing individualized dental hygiene care plans.

- Communication and Referral: It facilitates clear communication with patients, dentists, and other healthcare professionals, enabling appropriate referrals when necessary.

Crafting Effective Dental Hygiene Diagnosis Statements: Examples and Guidance

The ability to articulate a clear and concise dental hygiene diagnosis is paramount. These statements serve as the bridge between assessment and care planning. Here are examples and guidance to help you formulate effective DHDx statements:

General Principles for DHDx Statements:

- Patient-Centered: Focus on the patient’s needs and conditions, not just disease labels.

- Clear and Concise: Use easily understandable language for both professionals and patients.

- Specific: Be specific about the problem and its location or extent when possible.

- Linked to Evidence: Statements should be directly supported by assessment findings.

- Action-Oriented: Statements should guide the development of appropriate interventions and care plans.

Dental Hygiene Diagnosis Statement Examples – Categorized:

To provide practical application, let’s explore dental hygiene diagnosis statements examples across common clinical scenarios:

1. Gingival and Periodontal Conditions:

- Example: “Gingivitis associated with plaque biofilm and exacerbated by inadequate daily oral hygiene practices, as evidenced by generalized gingival inflammation, bleeding on probing, and moderate plaque accumulation.”

- Explanation: This statement clearly identifies the condition (gingivitis), the primary etiological factor (plaque biofilm), a contributing factor (inadequate oral hygiene), and the supporting evidence from the assessment.

- Example: “Periodontal disease risk due to history of smoking and presence of localized moderate periodontitis, as evidenced by probing depths of 4-5mm with bleeding on probing at sites #3, #14, and #29, and patient report of smoking half a pack of cigarettes daily.”

- Explanation: This statement highlights periodontal disease risk factors and the existing condition (localized periodontitis), linking it to specific clinical findings and patient history.

- Example: “Peri-implant mucositis around implant #19, secondary to biofilm accumulation, as evidenced by inflammation and bleeding on probing around the implant, with no signs of bone loss radiographically.”

- Explanation: This statement addresses a specific condition related to dental implants, identifying the cause and supporting evidence.

2. Caries Risk and Existing Caries:

- Example: “High caries risk due to frequent consumption of sugary beverages and snacks throughout the day, inadequate fluoride exposure, and presence of multiple areas of enamel demineralization.”

- Explanation: This statement identifies a high caries risk, listing specific contributing factors and clinical signs.

- Example: “Dental caries present on occlusal surface of tooth #30, as evidenced by visual examination and confirmed with radiographic findings.”

- Explanation: This statement clearly diagnoses existing caries, specifying the location and method of diagnosis.

- Example: “Risk for early childhood caries due to nighttime bottle feeding with juice and lack of parental awareness regarding early childhood caries prevention.”

- Explanation: This statement focuses on risk factors for a specific population, highlighting behavioral and knowledge deficits.

3. Oral Hygiene and Self-Care Deficits:

- Example: “Ineffective oral hygiene practices, related to lack of dexterity and knowledge deficit, as evidenced by generalized heavy plaque biofilm accumulation, calculus deposits, and patient’s verbalization of difficulty with toothbrushing due to arthritis.”

- Explanation: This statement diagnoses ineffective oral hygiene, linking it to contributing factors like physical limitations and knowledge gaps.

- Example: “Poor compliance with recommended oral hygiene regimen, possibly due to lack of perceived need and motivation, as evidenced by persistent gingival inflammation and patient’s inconsistent report of flossing.”

- Explanation: This statement addresses patient compliance issues, suggesting potential underlying reasons.

4. Other Oral Health Concerns:

- Example: “Potential for dentinal hypersensitivity related to gingival recession and toothbrush abrasion, as evidenced by patient complaint of sensitivity to cold stimuli on teeth #8, #9, and #25, and clinical observation of gingival recession and wedge-shaped defects.”

- Explanation: This statement addresses dentinal hypersensitivity, linking it to clinical observations and patient symptoms.

- Example: “Risk for oral cancer due to history of tobacco use and lack of regular oral cancer screenings.”

- Explanation: This statement highlights oral cancer risk based on patient history and preventive care patterns.

- Example: “Xerostomia potentially related to medication side effects, as evidenced by patient report of dry mouth, thick saliva, and medication history including antihistamines.”

- Explanation: This statement addresses xerostomia and suggests a possible contributing factor (medications).

Applying DHDx Statements in Case Scenarios:

Let’s revisit the case studies from the original article to see how these principles and examples apply.

Case Study A: Robert (12-year-old boy)

Instead of just listing diagnoses, we can formulate them as clear statements:

- “Uncontrolled asthma, requiring consideration for stress reduction protocols and potential medication interactions during dental hygiene care.”

- “Elevated risk for dental caries due to high frequency of sugary drink consumption and inadequate oral hygiene practices, necessitating intensive caries management and dietary counseling.”

- “Gingivitis associated with plaque biofilm accumulation, exacerbated by puberty, requiring comprehensive oral hygiene instruction and professional prophylaxis.”

- “Knowledge deficit regarding oral health prevention, impacting self-care practices and contributing to caries and gingivitis, necessitating targeted patient education for both Robert and his parents.”

- “Risk for traumatic dental injury due to participation in contact sports without a mouthguard, requiring recommendation and fabrication of a custom sports mouthguard.”

Case Study B: Mary (32-year-old pregnant woman)

- “Gingivitis associated with pregnancy and exacerbated by hyperemesis gravidarum, requiring gentle oral hygiene techniques, frequent professional care, and strategies to manage nausea during oral hygiene.”

- “Elevated risk for dental caries due to frequent vomiting associated with hyperemesis gravidarum and diet high in fermentable carbohydrates, necessitating intensive caries management, dietary counseling with a registered dietitian, and strategies to minimize enamel erosion.”

- “Peri-implant mucositis around implant #30, secondary to biofilm accumulation, requiring targeted biofilm management strategies and close monitoring.”

- “Poor oral self-care secondary to hyperemesis gravidarum, impacting biofilm control and contributing to gingivitis and caries risk, requiring modified oral hygiene techniques and supportive care.”

The Impact of Clear DHDx Statements on Patient Care

Formulating clear dental hygiene diagnosis statements examples is not just an academic exercise. It has profound implications for patient care:

- Enhanced Patient Understanding and Engagement: Patients are more likely to understand their oral health status and actively participate in their care when diagnoses are communicated clearly and understandably.

- Effective Care Planning: Well-defined diagnoses directly guide the development of targeted and effective dental hygiene care plans. Every planned intervention should logically flow from a diagnosed need.

- Improved Interprofessional Communication: Clear DHDx statements facilitate communication with dentists, physicians, and other healthcare providers, ensuring a collaborative approach to patient care, especially when referrals are necessary.

- Professional Accountability: Articulating diagnoses demonstrates the dental hygienist’s expertise and accountability in patient care, reinforcing their role as a diagnostician within their scope of practice.

Conclusion: Embracing Dental Hygiene Diagnosis for Optimal Outcomes

Dental hygiene diagnosis is an indispensable component of contemporary dental hygiene practice. By mastering the principles of DHDx and utilizing clear and effective diagnosis statements, dental hygienists can significantly enhance patient care. Moving forward, embracing the diagnostic role is crucial for dental hygienists to fully realize their potential in promoting optimal oral and overall health for their patients. Every dental hygiene care plan should be rooted in a comprehensive and well-articulated dental hygiene diagnosis.

References

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- United States Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2010 Standard Occupational Classification. Available at: bls.gov/soc/2010/2010_major_groups.htm. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- United States Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2018 Standard Occupational Classification. Available at: bls.gov/soc/2018/major_groups.htm. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- Gurenlian JR, Sanderson TR, Garland K, Swigart D. Exploring the integration of the dental hygiene diagnosis in entry-level dental hygiene curricula. J Dent Hyg. 2018;92:18–26.

- French KE, Perry KR, Boyd LD, et al. Variations in periodontal diagnosis among clinicians: dental hygienists’ experiences and perceived barriers. J Dent Hyg. 2018;92:23–30.

- Swigart DJ, Gurenlian JR. Implementing dental hygiene diagnosis into practice. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2015;13(9):56–59.

- Caton JG, Armitage G, Berglundh T, et al. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions—Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S1–S8.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Dental Hygiene Diagnosis: an ADHA White Paper. Available at: eiseverywhere.com/esurvey/index.php?surveyid=40570. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- Zill JM, Scholl I, Harter M, Dirmaier J. Which dimensions of patient-centeredness matter? Results of a web-based expert Delphi survey. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:1–15.

- Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL. Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. 8th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2013:106.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinician FAQ: CDC Recommendations for HPV Vaccine 2-Dose Schedules. Available at: cdc.gov/hpv/downloads/HCVG15-PTT-HPV-2Dose.pdf. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- Jenson L, Budenz AW, Featherstone JD, Ramos-Gomez FJ, Spolski VW, Young DA. Clinical protocols for caries management by risk assessment. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:714–723.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Best practices on periodicity of examination, preventive dental services, anticipatory guidance/counseling, and oral treatment for infants, children, and adolescents. Available at: aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/BP_Periodicity.pdf#page=5&zoom=auto,-274,495. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on Prevention of Sports-Related Orofacial Injuries. Available at: aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/P_Sports.pdf. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- Burkhart NW. Preventing dental erosion in the pregnant patient. RDH. 2012;32(1):72–73.

- Johnson CD, Koh SH, Shynett B, et al. An uncommon dental presentation during pregnancy resulting from multiple eating disorders: Pica and bulimia. Gen Dent. 2006;54:198–200.

- Lane MA. Effect of pregnancy on periodontal and dental health. Acta Odontol Scand. 2002;60:257–264.

- Gruppen LD, Frohna AZ. Clinical reasoning. In: Norman GR, van der Vleuten CPM, Newble DL, eds. International Handbook of Research in Medical Education. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2002:205–230.

- Ilgen JS, Eva KW, Regehr G. What’s in a label? IS diagnosis the start or the end of clinical reasoning? J Gen Intern Med. 2016:31:435–437.

- Cook DA, Sherbino J, Durning SJ. Management reasoning: Beyond the diagnosis. JAMA. 2018:319:2267–2268.

Dental hygiene diagnosis examples table

Dental hygiene diagnosis examples table

Table 1: Examples of Dental Hygiene Diagnosis Statements. This table provides further examples of dental hygiene diagnoses, linking assessment findings to potential diagnosis statements.