Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) stands as a significant global health challenge, ranking among the leading causes of mortality worldwide. Despite its prevalence and impact, COPD often remains underdiagnosed and receives insufficient prioritization within healthcare systems. This necessitates a critical review of existing healthcare policies to integrate COPD prevention and management as a paramount global health objective. This article aims to propose and elaborate on health system quality standard position statements designed for consistent implementation in the care of COPD patients.

Methods

In April 2021, a consortium of multidisciplinary clinicians specializing in COPD management, alongside patient advocates from eight nations, convened for a quality standards review meeting. The primary goal was to achieve a global consensus on health system priorities, ensuring uniform standards of care for COPD. The quality standard position statements formulated were grounded in evidence-based research and the collective expertise of the panel.

Results

Through collaborative discussions, the expert panel endorsed five quality standard position statements, each accompanied by a rationale, supporting clinical evidence, and essential criteria for quality metrics. These statements underscore critical aspects of COPD care: (1) timely and accurate diagnosis, (2) comprehensive patient and caregiver education, (3) accessible medical and non-medical treatments in accordance with the latest evidence-based recommendations, and specialist referral when indicated, (4) effective management of acute COPD exacerbations, and (5) consistent patient and caregiver follow-up for care plan evaluation.

Conclusions

These quality standards offer practical guidelines adaptable for implementation at local and national levels. While universally applicable to the fundamental elements of COPD care, they are designed to accommodate variations in healthcare resources, priorities, organizational structures, and care delivery capabilities across different healthcare systems. We advocate for the adoption of these global quality standards by policymakers and healthcare professionals to inform revisions in national and regional health system policies, ultimately enhancing the quality and consistency of COPD care worldwide, particularly within primary care settings.

Key Summary Points

| Quality standards encompassing the entire COPD care pathway, while acknowledging diverse healthcare system architectures globally, are currently lacking. |

|---|

| Global COPD experts, including clinicians and patient advocates from eight countries, reached a consensus on essential global standards of care for COPD. |

| The proposed quality standard position statements emphasize core components of COPD detection and treatment: (1) diagnosis, (2) patient and caregiver education, (3) access to evidence-based medical and non-medical treatments and specialist management when necessary, (4) acute exacerbation management, and (5) regular follow-up for personalized care plan reviews. |

| These quality standards, while ambitious, are designed with customization in mind, making them measurable and achievable within diverse healthcare systems. |

| Global adoption of these standards is recommended to ensure consistent and optimal COPD care across all disease stages, especially within primary care. |

Digital Features

This article is enhanced with digital features, including an infographic, to facilitate a deeper understanding. Digital features can be accessed at 10.6084/m9.figshare.19368125.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a prevalent, preventable, and progressive condition marked by persistent respiratory symptoms [1]. The 2016 Global Burden of Disease Study reported 251 million individuals living with COPD [2], and by 2019, it had become the third leading cause of global mortality [3]. Beyond exacerbations, COPD is associated with various extrapulmonary manifestations [4–8]. Effective COPD management focuses on alleviating symptom severity, reducing exacerbation risk, preserving functional status and quality of life (QoL), and decreasing disease-related mortality. A holistic approach to care, consistent with the latest evidence-based treatment guidelines, is crucial [1].

Adherence to treatment regimens aligned with Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recommendations demonstrably reduces exacerbation risk, COPD-related healthcare resource utilization (HCRU), and associated medical costs [9]. While guidelines [1, 10, 11] aim to optimize COPD management, their global implementation remains inadequate [12–18], leading to significant gaps in clinical care standards, especially within primary care settings. Guideline dissemination and adaptation are particularly deficient in low- and middle-income countries, where integrated disease management approaches face feasibility challenges [19–21]. Although guideline-directed treatment offers clinical benefits, guidelines alone often fail to drive systemic policy changes or alter practices across primary, secondary, and tertiary care. Despite being a leading cause of death, COPD is often underdiagnosed and underprioritized in healthcare systems [22]. Therefore, COPD must be a core component of global health agendas, and healthcare priorities should be reassessed to emphasize COPD prevention and management as a global public health imperative, particularly within primary care. Initiatives like the WHO Global Noncommunicable Diseases (NCDs) Action Plan [23] and the UN Decade of Healthy Ageing program [24] aim to enhance the accessibility, affordability, and consistency of COPD care worldwide.

Quality standards are concise statements addressing unmet diagnostic and treatment needs in specific diseases. They guide healthcare practitioners in delivering optimal, evidence-based disease management [25]. Quality standards complement guidelines, reinforcing appropriate clinical behaviors. National COPD quality standards exist in countries like the UK, USA, Spain, Germany, and Canada [25–31], but comprehensive standards spanning the entire COPD care pathway are lacking. Performance improvement tools, such as the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), used in the USA to evaluate COPD care effectiveness, require updates. Local and national COPD quality standards must remain current with evidence-based recommendations to maximize effectiveness. Crucially, global COPD quality standards adaptable to diverse healthcare system structures and data-sharing networks are urgently needed. This article details quality standard position statements developed to ensure actionable standards of care, reflecting global diagnostic and treatment recommendations for all COPD patients. These statements target policymakers, healthcare practitioners, primary care physicians, and patient groups, promoting consistent care across all COPD stages through multidisciplinary collaboration, especially within primary care.

Methods

A virtual meeting on April 22, 2021, facilitated the development of quality standard position statements through evidence review and discussion by international COPD experts. Experts were selected based on publication history, leadership in policy revision initiatives, and clinical expertise. This multidisciplinary group, including clinicians and patient advocates from eight countries, achieved consensus on global quality standard position statements for COPD care. These statements were primarily formulated from patient charter principles [32] and refined to drive policy changes aimed at reducing COPD burden. Key considerations included: (1) patient-centricity, recognizing individual needs and cultural diversity; (2) practicality, adaptability, and ambitious yet achievable goals with measurable metrics; and (3) easy implementation across diverse healthcare systems, fostering global partnerships. These quality standard position statements are based on current evidence, updated clinical strategies like GOLD [1], and the clinical experience of the contributors. This article is based on expert consensus and does not involve studies with human or animal participants.

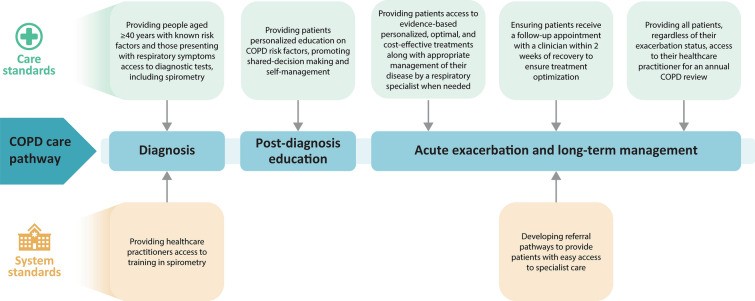

Following deliberation, experts agreed on five quality standard position statements, detailing their rationale, clinical evidence, and implementation criteria. These statements define core elements for improving COPD care quality and consistency: (1) accurate diagnosis, particularly in primary care; (2) comprehensive patient and caregiver education; (3) access to evidence-based medical and non-medical therapies, and specialist referral when needed; (4) effective acute exacerbation management; and (5) regular patient and caregiver follow-up for individualized care plan reviews (Fig. 1). Quality indicators and metrics were also proposed to monitor adoption progress within healthcare systems, especially within primary care settings.

Fig. 1.

Core elements of COPD care. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Results

Figure 2 provides an overview of the core elements of the quality standard position statements across the COPD care pathway, highlighting their relevance in primary care.

Fig. 2.

Specific gaps in the COPD care pathway addressed by the proposed quality standards. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Quality Standard Position Statement 1 (Diagnosis)

Individuals at risk and healthcare practitioners, particularly in primary care, should be vigilant in recognizing COPD risk factors and early symptoms. Clinicians should have ready access to appropriate diagnostic tools for informed, timely, and accurate diagnosis.

Rationale

Clinical diagnosis of COPD relies on medical history and physical examination, considering risk factors, symptoms, exacerbations, and comorbidities [1]. Spirometry confirms COPD by demonstrating poorly reversible airflow limitation [1]. However, a database study showed only about one-third of patients suspected of COPD underwent spirometry [33]. Timely, accurate diagnosis requires spirometry in primary care, where patients often present with early symptoms or risk factors. Multidisciplinary primary care teams, including nurses, are crucial in ensuring diagnostic confirmation [34]. Yet, many primary care professionals lack formal spirometry administration and interpretation training [35], with cost and device access being further barriers. Reimbursement for spirometry is essential in primary care. Countries with spirometry reimbursement and financial incentives for primary care physicians show higher testing rates [34, 36]. Healthcare systems must ensure providers are trained, compensated, and experienced in spirometry for suspected COPD cases, and proactively repeat lung function tests in at-risk patients with borderline FEV1 values.

Machine learning/artificial intelligence may enhance the accuracy of ATS/ERS spirometry interpretation algorithms [37]. However, spirometry may miss early COPD stages, necessitating procedures like chest CT scans, body plethysmography, and diffusion capacity tests [38]. Clinicians should recognize that 17–24% of patients without spirometric COPD criteria may still experience respiratory symptoms, exacerbations, and activity limitations with airway disease evidence [39, 40]. Notably, some patients with preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) progress to COPD and face increased risks of respiratory issues and mortality [41–43]. Current GOLD guidelines do not address PRISm management, representing a possibly underdiagnosed heterogeneous population. Further research is needed to identify PRISm-related conditions and potential treatments. Also, post-bronchodilator airflow obstruction does not always indicate COPD, especially in low- and middle-income regions with high tuberculosis (TB) prevalence [44].

A COPD diagnosis, being chronic and progressive, should be communicated with culturally appropriate educational materials in patients’ native languages, considering varying health literacy levels. Content and formats may need adjustment for specific healthcare systems. Educating primary care physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals is vital for patient instruction and fostering physician-patient partnerships in COPD care.

COPD typically presents in middle-aged or older adults, often asymptomatically in early stages or with mild symptoms overlapping with other conditions, leading to underreporting [45]. Social stigma associated with aging, smoking, or environmental exposures may deter patients from seeking timely help [32]. Consequently, 65–80% of COPD cases remain undiagnosed [46]. While evidence of early treatment benefits is limited [47, 48], smoking cessation can slow mild COPD progression [48]. Early, accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment can mitigate deterioration [26]. All patients should access resources, including COPD risk factor and symptom education, and clinical consultation for timely evaluation and diagnosis [32]. Case-finding strategies targeting at-risk individuals or groups are practical for identifying early-stage patients [49]. Tools like COPD Assessment in Primary Care To Identify Undiagnosed Respiratory Disease and Exacerbation Risk (CAPTURE™) can help identify symptomatic patients with mild-to-moderate airflow obstruction who could benefit from comprehensive COPD assessment [50].

Essential Criterion 1A

Individuals should have access to spirometry performed by trained healthcare professionals in pulmonary function tests to ensure accurate COPD diagnosis, particularly within primary care settings.

Essential Criterion 1B

All individuals over 40 with COPD risk factors (smoking, environmental/occupational exposures to dusts, chemicals, fumes [51]) or respiratory symptoms should have access to diagnostic pulmonary function testing, and as-needed imaging and biomarker assessments, especially within primary care.

Quality Indicators/Metrics

- Proportion of individuals with respiratory symptoms and/or risk factors suspected of having or being at risk of COPD identified in primary care.

- Proportion of individuals undergoing timely and accurate spirometry to confirm or exclude COPD following clinical suspicion or risk assessment in primary care.

- Proportion of COPD patients with documented quality-assured spirometry [52] in primary care records.

- Time from first symptom presentation to spirometry-confirmed diagnosis in primary care.

Quality Standard Position Statement 2 (Adequate Patient and Caregiver Education)

Patients, particularly in primary care settings, should receive education on COPD risk factors, symptoms, exacerbations, and the importance of self-management. Caregivers should also be included in educational initiatives to improve patient outcomes.

Rationale

COPD is symptomatically heterogeneous, with daily, weekly, and seasonal variability [53]. Morning symptoms like dyspnea, cough, and sputum production are common [54]. Nocturnal symptoms and sleep disturbances, often underrecognized, may correlate with lung function changes, exacerbation frequency, and comorbidities like cardiometabolic diseases and depression [55, 56].

COPD risk factors include tobacco smoke, occupational exposures, air pollution, lower socioeconomic status, congenital lung abnormalities, and genetic predisposition [1, 57–60]. While GOLD guidelines focus on cigarette smoking [1], other tobacco use forms (pipes, cigars, hookahs) also significantly increase COPD risk [61, 62]. In utero and early-life tobacco exposure, low birth weight, respiratory infections, and childhood asthma are also COPD risk factors [63]. Patients need education on COPD symptom types, onset, frequency, and severity [32]. National awareness campaigns can encourage symptom recognition and evaluation without stigma.

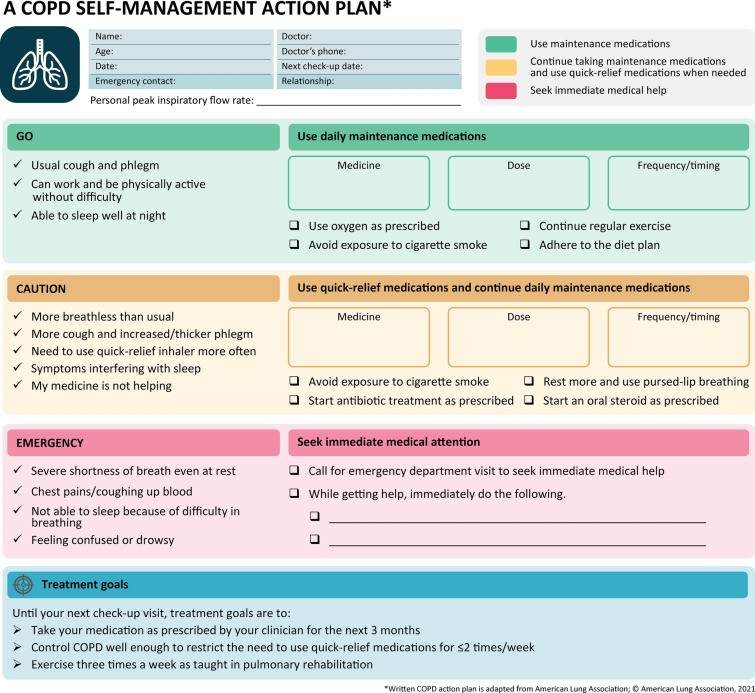

COPD self-management strategies, especially individualized action plans (Fig. 3) for exacerbation prevention, structured education, tailored case management, and healthcare network access, are critical [64, 65]. Healthcare practitioner engagement influences action plan impact and may require adjustments for health literacy and healthcare access [66, 67]. Action plans should be personalized with SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, time-bound) treatment goals. Other self-management strategies include smoking cessation, reducing irritant/infection exposure, exercise, medication adherence, and nutrition. Coping skills, vaccinations, breathing techniques (pursed-lip breathing, huff cough), and safe oxygen therapy also help [1, 64, 68]. COPD self-management interventions are linked to reduced symptoms, hospital admissions, and improved HRQoL [69]. Patients need personalized education on COPD and comorbidity interactions to actively participate in care and report changes to prevent exacerbations and progression [32]. Caregivers significantly contribute to COPD patient care. Educational sessions for patients and caregivers improve clinical outcomes [70]. Healthcare systems could reimburse these educational activities to promote uptake in primary care.

Fig. 3.

An example of a COPD action plan. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Shared decision-making among practitioners, patients, and caregivers enhances patient involvement and treatment compliance. This is crucial for older patients with comorbidities, ensuring treatment goals are met with minimal adverse effects and daily life disruption [71]. Shared decision-making and patient engagement (SDM-PE) showed benefits in a randomized controlled trial of hospitalized acute COPD exacerbation patients. SDM-PE improved perceived health status at discharge, COPD knowledge, medication adherence, and functionality at 3-month follow-up compared to standard treatment alone [72]. Active engagement in shared, informed decision-making and patient confidence in self-management are vital for maximizing clinical benefits, especially within primary care.

Essential Criterion 2

Patients in primary care should receive personalized education on risk factors, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up, tailored to their needs and abilities. They should be actively involved in decision-making and their self-management plans.

Quality Indicators/Metrics

- Proportion of confirmed COPD patients in primary care with documented education on risk factors, symptom identification, and disease management.

- Proportion of confirmed COPD patients with documented self-management plans, including action plans, recorded in primary care.

Quality Standard Position Statement 3 (Treatment Aligned with the Latest Evidence-Based Recommendations)

Patients, particularly in primary care, should have access to evidence-based, personalized treatments and appropriate specialist management when needed.

Rationale

While the GOLD strategy report is widely recognized, its dissemination and implementation are suboptimal in primary and specialist care settings globally [12–18], and it lacks resource-stratified recommendations. Many COPD patients are managed in primary care, presenting unique challenges. Primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants report limited awareness and application of COPD guidelines, and limited knowledge of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, including pulmonary rehabilitation [73]. Time constraints in primary care further complicate patient management [74]. Consequently, COPD misdiagnosis and misclassification are more common in primary care than specialist settings [75]. A global physician survey indicated respiratory specialists focus more on spirometry and disease trajectory, while primary care physicians prioritize treatment history and symptoms for diagnosis and treatment decisions [76]. The National Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Audit Program in the UK showed specialist COPD care within 24 hours of hospitalization reduced inpatient mortality and increased smoking cessation initiatives [77]. Streamlined referral pathways are essential for timely and appropriate patient transfer within healthcare systems. Respiratory therapists, working across care settings, significantly contribute to respiratory care by addressing community cardiorespiratory health needs, providing education, improving policies, and developing treatment protocols [78]. Pharmacists can also support COPD patients by addressing medication queries, administration frequency, and adverse effects, and facilitating specialist referrals [79]. Access to specialist care can be geographically challenging. A US study showed only 34.5% of rural COPD patients had a pulmonologist within a 10-mile radius in 2013 [80]. Telehealth consultations can overcome geographical barriers, but virtual diagnostics have limitations [81]. Smartphone-connected spirometry may monitor existing COPD patients, but its diagnostic use for new cases is not fully established [82], and it may not be suitable for all severe patients long-term. Patient care should not be limited by digital exclusions or socioeconomic background, especially in primary care.

COPD management includes pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments [1]. However, patient access to appropriate and affordable care faces gaps. Despite GOLD recommendations for inhaled bronchodilator maintenance therapy [1], about two-thirds of US patients were not prescribed maintenance inhalation therapy [83]. A UK analysis showed up to three-quarters of patients with at least two exacerbations were undertreated according to GOLD 2019 guidelines [13]. Patients need access to evidence-based and cost-effective therapies for effective COPD management within healthcare budgets [84]. Correct inhaler technique is vital; patients need training and regular re-evaluation. Inhaler device choice should be patient-tailored, considering drug cost, patient preference, and inhalation therapy freedom of choice [1]. Nonpharmacological interventions complement pharmacological treatments and should be part of comprehensive COPD management plans [1]. Post-discharge pulmonary rehabilitation reduces mortality in patients hospitalized for exacerbations [85]. Limited access to smoking cessation support, pulmonary rehabilitation, and immunizations hinders effective COPD management [86]; these nonpharmacological treatments should be more accessible, especially within primary care.

Essential Criterion 3A

Patients in primary care should have timely access to assessment, diagnosis, and medical intervention, in institutional or community settings. Healthcare systems should establish reliable referral systems for transitions from primary to secondary or tertiary care when necessary.

Essential Criterion 3B

Patients should have access to cost-effective, optimal, evidence-based pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments informed by clinical guidelines, especially within primary care.

Quality Indicators/Metrics

- Proportion of patients consulting a respiratory specialist or practitioner with respiratory expertise (including primary care) according to local/national guidelines.

- Time from clinical COPD suspicion to spirometry-confirmed diagnosis, specifically in primary care.

- Time from COPD diagnosis confirmation to specialist review (as defined above) when referral is needed, according to guidelines, tracked from primary care referral.

- Proportion of COPD patients whose care aligns with evidence-based treatment recommendations, including smoking cessation, vaccinations, pulmonary rehabilitation, and pharmacotherapy, within primary care.

Quality Standard Position Statement 4 (Post-exacerbation Management)

Patients, particularly in primary care follow-up, should have timely management plan reviews after acute COPD exacerbation recovery to prevent recurrent exacerbations and disease progression.

Rationale

Patients report exacerbations as the most disruptive aspect of COPD, often leading to hospital or emergency department visits [87]. COPD exacerbations increase cardiovascular event risks (myocardial infarction, stroke [88 and mortality [89, and accelerate lung function decline [89, 90]. Exacerbation history strongly predicts future exacerbations [91]. A large database study showed subsequent severe exacerbation risk increasing threefold after the second exacerbation and 24-fold after the tenth versus the first [92]. However, medical reviews and management plan reassessments post-exacerbation are suboptimal [32], with only about one-quarter of patients with exacerbation history receiving adequate follow-up [93]. Hospitalized exacerbation patients should receive care from a respiratory specialist team and a personalized written/digital management plan at discharge [94]. A cohort study showed over one in five COPD patients died within a year of discharge [95]. Patients should be re-evaluated within 2 weeks of discharge to optimize therapy and improve outcomes [26, with primary care playing a crucial role in this follow-up. While exacerbations often require systemic corticosteroids or antibiotics [1], both have adverse effects. Long-term corticosteroid use is linked to osteoporosis, hyperglycemia, infections, ocular complications, and cardiovascular events [96], while inappropriate antibiotic use promotes bacterial resistance [97]. Patients need education on exacerbation prevention and management, and the importance of follow-up to minimize negative impacts [90], with primary care reinforcing these messages.

Essential Criterion 4

Following a COPD exacerbation, patients should be reviewed within 2 weeks of non-hospitalized exacerbation treatment onset or exacerbation-related hospital discharge to optimize treatment, especially in primary care follow-up.

Quality Indicator/Metrics

- Proportion of patients receiving a review within 2 weeks of non-hospitalized exacerbation treatment onset or 2 weeks post-exacerbation hospital discharge, and overall time from exacerbation onset to post-exacerbation review, particularly tracked in primary care.

- Proportion of patients referred for pulmonary rehabilitation after an exacerbation, documented in primary care records.

Quality Standard Position Statement 5 (Regular Patient Review)

All COPD patients should have annual evaluations, regardless of exacerbation history, and more frequent reviews after exacerbations, to ensure tailored care plan appropriateness and adequacy, especially within primary care.

Rationale

COPD exacerbations often initiate healthcare system interactions. However, healthcare systems should also support patients without exacerbations or those with symptoms overlapping other respiratory diseases [98], and this is particularly relevant in primary care. Even stable patients need regular re-evaluation to assess symptom control, comorbidities, physical activity levels, exercise capacity, and treatment needs [1]. Practitioners should assess therapeutic effectiveness and adverse effects to determine pharmacological or nonpharmacological treatment modifications. Patient action plans should be reviewed and updated [1]. COPD patients should be re-evaluated at least annually for treatment adherence, inhaler technique, side effects, mild exacerbations, follow-up spirometry, and GOLD risk assessment, ideally within primary care. Caregiver attendance at follow-up appointments should be facilitated to incorporate their health perception of the patient [99]. Given COPD’s association with cognitive, mobility, and auditory disabilities [100], a holistic preventive care approach, including smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation, and patient/caregiver education beyond exacerbation management, is crucial, and primary care is central to this ongoing support.

Essential Criterion 5

All COPD patients, regardless of exacerbation status, should have annual reviews by suitably trained practitioners, especially within primary care.

Quality Indicator/Metrics

- Proportion of confirmed COPD patients receiving at least annual reviews, documented in primary care records.

Discussion

Despite available evidence-based guidelines, including GOLD, significant gaps persist in COPD prevention, identification, and care. This expert group developed five quality standard position statements to improve COPD care globally. These standards maintain patient-centricity from prior COPD patient charter principles [32], refined to guide practitioners, policymakers, patients, and caregivers towards high-quality, priority COPD care, driving global disease management improvements based on best evidence, especially within primary care.

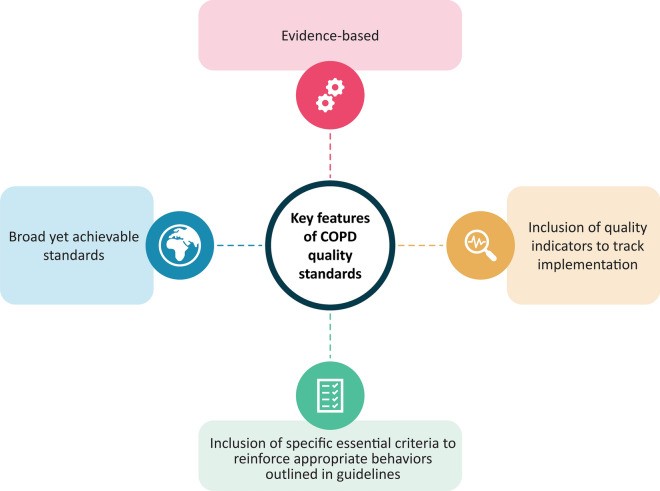

While ambitious, these quality standards are customizable and measurable within healthcare systems. All quality standards must be tailored to individual healthcare system needs, with indicators measured contextually (Fig. 4). Implementation extent can be monitored using methods appropriate for each healthcare system, from case-finding tools and questionnaires to EMRs, insurance claims, and clinical audits. However, methodological limitations must be considered. EMR use assumes routine and accurate data recording [101]. Patient surveys may have self-reporting and recall biases [102]. Clinical audits overcome some limitations, measuring outcomes against evidence-based standards [52]. We avoided specific measurement recommendations to allow adaptation to individual healthcare system infrastructure and resources. Not all position statements apply to all target groups. Primary, community, secondary, and tertiary care services must ensure reliable referral pathways for smooth patient transitions. Addressing primary care clinicians’ knowledge gaps in referral pathways requires CME focusing on parameters warranting timely specialist referral. Healthcare practitioners need adequate training and CME in spirometry and inhaler technique, and improved awareness and application of evidence-based treatment guidelines for COPD case management. Policymakers should establish national provisions and incentives, creating a framework to optimize COPD care through expanded education for practitioners, patients, and caregivers, improved access to specialist care and treatments, and prioritizing COPD management commensurate with its public health importance. COPD patients need ongoing instructions on risk factors, early symptom recognition, self-management, and active engagement in shared decision-making to optimize outcomes, with primary care being the cornerstone of this effort.

Fig. 4.

Key features of COPD quality standards. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Several global initiatives aim to improve COPD care access, affordability, and quality. The WHO Global NCDs Action Plan (2013–2020) seeks to reduce NCD burden, including COPD, through multisector cooperation [23]. The European Lung Health Group’s Breathe Vision envisions respiratory health policy decisions centered on diagnosis, cure, and disease management by 2030 [103]. The UN Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030) promotes global collaboration to improve older persons’ lives [24], relevant to COPD as it primarily affects middle-aged and older adults [1]. The US COPD National Action Plan outlines practical ways to educate the public and improve COPD prevention, diagnosis, and treatment [104]. The CONQUEST program, a collaborative COPD registry with quality improvement, mobilizes targeted, risk-based management through enhanced clinical assessment [29], demonstrating quality standard integration into healthcare systems and clinical practice improvements [29]. We anticipate these global quality standard position statements and ongoing initiatives will enhance COPD understanding and position it as a global public health priority, reducing COPD mortality, particularly through strengthened primary care.

Implementation challenges include disparities between well-resourced and resource-limited healthcare systems. Healthcare infrastructure, delivery systems, health literacy, and cultural norm differences may necessitate adaptations [105]. A “one size fits all” approach to COPD diagnosis, treatment, and control will not succeed in diverse settings, especially in primary care. Quality standard position statements may require refinement based on local needs, models, and resources. These global quality standard position statements are adaptable regionally and nationally. Healthcare systems can modify and implement them, measure quality indicators, assess alignment with model standards, revise quality improvement plans, remeasure indicators, and establish quality improvement trajectories to achieve aspirational goals, starting with primary care enhancements.

This publication is a first step towards awareness and policy revision. Further strategies are needed for dissemination and long-term implementation of these global quality standards. We have proposed quality indicators for each statement. A practical, adaptable “tool kit” should be developed for active dissemination across platforms, including print, social media, and multichannel awareness, maximizing outreach to patients, caregivers, practitioners, and policymakers. Simple, educational infographics with visual elements can be shared through CME courses and social media. As governments and healthcare systems recover from COVID-19, prioritizing COPD as a public health issue can support healthcare system recovery and sustainability by reducing unnecessary emergency service burden and HCRU associated with chronic respiratory diseases, with primary care playing a vital role in long-term management and prevention.

Conclusion

These global quality standard position statements aim to provide core elements of essential, universal COPD care, based on high-quality evidence for embedding in global health systems to improve clinical outcomes. We urge policymakers and healthcare practitioners to recognize COPD as a global public health priority and adopt these statements as a critical step towards consistent COPD care across all disease stages, especially by strengthening diagnosis and management within primary care.

Supplementary Information

Electronic supplementary material is available at: Supplementary file1 (PDF 4358 KB)

Acknowledgements

Funding

AstraZeneca funded the development of this manuscript, including journal fees.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Writing and editorial support was provided by Saurabh Gagangras of Cactus Life Sciences, funded by AstraZeneca.

Authorship

All authors meet ICMJE criteria for authorship and responsibility for the work, and approved the publication. Authors were not compensated.

Author Contributions

All authors met ICMJE criteria, contributed equally to conception and reviews, and take full responsibility for content.

Disclosures

Detailed author disclosures are provided in the original publication.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on expert consensus and does not involve human or animal studies.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no datasets were generated or analyzed.

References

[References]

Associated Data

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 (PDF 4358 KB)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no datasets were generated or analyzed.