Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic and progressive liver disease affecting the bile ducts. Characterized by inflammation and fibrosis, PSC leads to the destruction of bile ducts both inside and outside the liver. As a specialist from xentrydiagnosis.store, while my primary expertise lies in automotive diagnostics, understanding complex systems and their failures is universal. In PSC, it’s the biliary system that’s malfunctioning. This review delves into the critical role of diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy in the diagnosis and management of PSC, an area where precision and expertise are paramount, much like in automotive repair.

UNDERSTANDING PRIMARY SCLEROSING CHOLANGITIS (PSC)

PSC is a long-term condition that, while its exact progression is unpredictable, typically advances slowly towards biliary cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease in many patients[1]. It predominantly affects men, often manifesting in their 30s and 40s. Currently, liver transplantation remains the only proven intervention to significantly improve survival rates for PSC patients [1, 2]. A significant comorbidity, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), particularly ulcerative colitis, is present in 60%-80% of PSC cases [3]. The exact causes and mechanisms of PSC are still not fully understood, making it a challenging condition to manage.

In clinical practice, specialists are frequently consulted when patients, especially those with IBD, present with abnormal liver function tests. The crucial steps involve accurately diagnosing PSC, monitoring for complications such as dominant strictures, and excluding cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), a significant risk in PSC patients. The therapeutic endoscopist is central to this process, providing essential diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. This review aims to clarify the role of therapeutic endoscopy in PSC management, drawing on current literature and clinical experience to propose a practical management algorithm.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACHES FOR PSC

Diagnosing PSC relies on a combination of typical cholestatic biochemical profiles and detailed visualization of the biliary tree. Cholangiography is key, with characteristic findings including multifocal, short strictures alternating with normal or dilated segments, creating a distinctive “beaded” appearance [4]. Both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts are usually involved. In a minority of cases, the disease may be confined to the intrahepatic ducts, and isolated extrahepatic PSC is rare.

Historically, liver biopsy was considered for PSC diagnosis. However, it has largely been superseded by imaging techniques for several reasons. Histological features from liver biopsies in PSC are often non-specific [5]. Periductal fibrosis, or “onion skinning,” once considered pathognomonic, is not consistently observed [5]. Furthermore, studies have shown that PSC’s histological presentation can be patchy, with different stages potentially present within a single liver at any given time, indicating significant sampling variability [6]. Modern prognostic models for PSC generally do not include histological staging as a variable, further diminishing the diagnostic role of liver biopsy [7]. While liver biopsy may not routinely add diagnostic value for PSC itself [8], it remains relevant in identifying co-existing liver conditions, such as autoimmune hepatitis in overlap syndromes, which may influence treatment strategies. Biopsy is also essential in diagnosing small duct PSC, where cholangiography is typically normal.

Cholangiography remains the cornerstone for visualizing the biliary tree. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was once the gold standard. However, due to its invasive nature and associated risks, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is now favored as a safer initial diagnostic tool. Early studies comparing MRCP to ERCP demonstrated comparable diagnostic accuracy. One study reported MRCP accuracy at 90% versus ERCP’s 97% [9]. A meta-analysis of six studies confirmed high sensitivity (86%) and specificity (94%) for MRCP [10].

While MRCP and ERCP offer similar diagnostic accuracy, MRCP may not always optimally visualize bile ducts, especially in early PSC stages. In cases where MRCP is inconclusive, ERCP may still be necessary to definitively exclude PSC. Despite being invasive, ERCP, particularly in experienced centers, carries a low risk of adverse events. One study reported a 4.3% adverse event rate in a large cohort undergoing ERCP for PSC, including both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures [11]. Therefore, while MRCP is generally recommended as the first-line imaging test for PSC diagnosis, ERCP remains crucial for cases with non-diagnostic MRCP and when therapeutic interventions for bile duct strictures are needed. Many centers, including ours, adopt a protocol of initial MRCP followed by ERCP if MRCP is non-diagnostic or when therapy is indicated.

MANAGING DOMINANT STRICTURES IN PSC

Worsening symptoms in PSC patients often necessitate investigation for dominant extrahepatic biliary strictures. A dominant stricture is defined as a stenosis with a diameter of ≤ 1.5 mm in the common bile duct or ≤ 1 mm in the hepatic duct [12]. These significant strictures occur in 36%-57% of PSC patients [12]. Clinical indicators for treatment initiation include right upper quadrant pain, jaundice, pruritus, and cholangitis. Elevated bilirubin levels, common bile duct strictures, and dominant strictures are predictors of successful outcomes following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP), marked by clinical and laboratory improvements [13]. These factors can help identify patients most likely to benefit from ERCP versus those who might be managed conservatively. Endoscopic balloon dilatation, with or without stenting, are the primary endoscopic techniques employed.

Figure 1

Figure 1

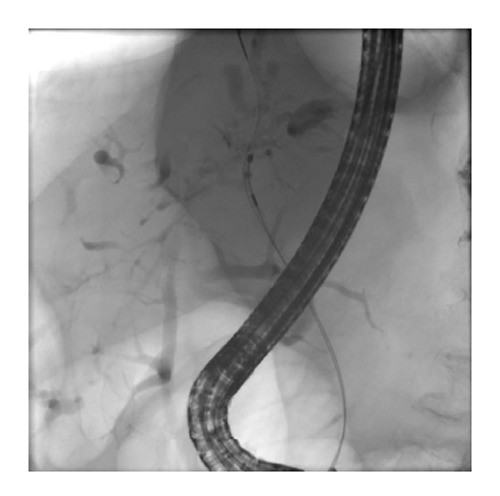

Figure 1: Depiction of left hepatic duct dominant stricture undergoing brushing for cytology during ERCP. The alt text aims to be descriptive and SEO-friendly, including keywords like “ERCP,” “cytology,” “hepatic duct,” and “biliary stricture.”

The effectiveness of ursodeoxycholic acid combined with or without endoscopic therapy on survival is complex to determine due to study limitations. Early research on endoscopic balloon dilatation in symptomatic patients showed improvements in bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase levels, and radiographic stricture scores [15]. However, other studies analyzing outcomes of biliary stricture management found that endoscopic balloon dilatation, with or without stenting, did not significantly change bilirubin levels in a subset of patients [16]. Some research suggests that intrahepatic strictures may indicate poorer prognosis [18, 19], potentially influencing decisions regarding intervention on extrahepatic strictures. Identifying ideal candidates and definitive indications for therapeutic endoscopy requires further long-term studies.

The search for the optimal endoscopic treatment approach continues. A retrospective study found no significant difference in outcomes between endoscopic dilation alone versus dilation plus stenting in improving cholestasis. The stenting group, however, experienced a higher rate of complications, suggesting this group may have had more severe disease initially, as stenting was often reserved for cases where dilation alone was insufficient [20, 21]. A randomized controlled trial comparing short-term stenting and balloon dilatation for dominant strictures is underway (NCT01398917) and is expected to provide clarity on the best approach. Plastic stents are considered a preferred option for benign dominant extrahepatic biliary strictures [22].

Endoscopic therapy has shown promising long-term outcomes. One study reported positive long-term results with repeated endoscopic dilations in patients followed for 20 years, with notable 5-year and 10-year survival rates [23]. Short-term stenting (up to 11 days) has been associated with fewer complications such as cholangitis/jaundice and effective symptom reduction and biochemical improvement [24]. These complications are often linked to stent occlusion. Further studies support short-term stenting for symptom relief and biochemical cholestasis resolution, with many patients remaining re-intervention-free at one year [25, 26]. One study even suggested a survival benefit from endoscopic treatment of strictures compared to predicted survival based on the Mayo risk score [27], although this requires cautious interpretation. Other studies have echoed these findings [28, 29].

However, some research has not found significant differences in bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels between PSC patients with and without dominant strictures [11]. Similarly, patients with small duct PSC, who have normal cholangiograms, do not consistently show different bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels compared to large duct PSC patients [30, 31]. Randomized trials comparing endoscopic and non-endoscopic therapies for dominant strictures are needed to resolve these discrepancies.

It’s important to consider that in pre-malignant conditions like PSC, cancer risk may increase with disease duration. However, endoscopic treatment of biliary strictures could potentially mitigate inflammation and delay cancer development. Furthermore, improved cancer detection methods and increased awareness may lead to earlier CCA diagnosis, potentially creating lead-time bias in survival studies of endoscopic therapy [27]. Interestingly, the same study suggesting survival benefits from endoscopic treatment did not find an increased cancer frequency. Similarly, a multi-center study did not link PSC duration with increased CCA incidence [32].

Despite treatment, dominant strictures generally indicate a poorer prognosis. A long-term prospective study reported reduced liver transplant-free survival in patients with dominant stenoses [33]. Another study linked dominant stenoses with IBD to an increased risk of various malignancies, including biliary, gallbladder, and colorectal cancers, and reduced survival [34]. Notably, most patients with dominant stenoses in this study received endoscopic treatment. A study following PSC patients found that those with dominant stenoses had more advanced histological PSC stages and reduced survival compared to those without. Importantly, after excluding patients with CCA, the survival difference was no longer statistically significant, and all CCA cases developed in patients with dominant strictures [35, 36]. This underscores the need for early detection of dominant strictures and accurate differentiation between benign and malignant strictures.

Our clinical approach typically favors balloon dilation alone for dominant strictures in PSC patients. Stenting is reserved for refractory strictures or cholangitis cases, using short-term stents removed within 10-14 days. We also recommend post-procedure oral antibiotics to minimize cholangitis risk. This protocol has shown a low overall adverse event rate in our practice [11], with cholangitis remaining the most common complication.

CHOLANGIOCARCINOMA (CCA) SCREENING IN PSC

The risk of developing CCA in PSC patients is significant, increasing to approximately 9% after 10 years and 19% after 20 years [37]. Therefore, effective CCA screening is a critical aspect of PSC management. While definitive guidelines are still evolving, tumor markers and imaging modalities are key components of surveillance strategies. Cancer antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) levels > 130 U/mL in symptomatic patients show high sensitivity and specificity for CCA [38]. Imaging modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have varying sensitivities, with MRI often preferred for its detailed biliary imaging [39].

Bile duct brushings during ERCP are routinely used for tissue sampling in suspected CCA (Figure 1). However, brush cytology alone has limitations, with meta-analyses showing high specificity but modest sensitivity [40]. Advanced techniques aim to improve diagnostic yield.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is one such technique, detecting chromosomal abnormalities common in cancer cells. Aneuploidy, or abnormal chromosome numbers, is more prevalent in CCA associated with PSC compared to PSC alone [41, 42]. Studies have shown that FISH can improve sensitivity compared to routine cytology in diagnosing malignant pancreaticobiliary strictures, although specificity may be slightly lower [43, 44]. Elevated CA 19-9 levels combined with FISH polysomy can strongly predict malignancy risk, especially when imaging is inconclusive [45]. However, not all FISH abnormalities indicate cancer risk, with some studies showing similar outcomes in patients with certain FISH abnormalities and those with negative FISH results [46]. Meta-analyses indicate moderate FISH sensitivity with high specificity, but the overall diagnostic accuracy remains debated [47]. Serial polysomy testing may help monitor risk, with persistent polysomy correlating with higher CCA development rates [48].

Newer diagnostic methods are emerging, focusing on aspects of cancer biology like angiogenesis. Probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy (pCLE) can detect neovascularization in biliary strictures. Studies report high sensitivity for pCLE in diagnosing biliary malignancies, but specificity varies [49, 50, 51, 52, 53]. One study specifically in PSC patients showed 100% sensitivity and negative predictive value for pCLE [54]. Intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS) is another valuable tool for analyzing dominant strictures, showing superior sensitivity and specificity compared to ERCP in some studies [55].

Peroral cholangioscopy offers direct visualization of bile ducts, improving diagnostic accuracy. Studies have shown higher specificity for cholangioscopy compared to ERCP alone in PSC patients with dominant stenoses [56]. Narrow band imaging (NBI) enhances mucosal surface visualization and may increase biopsy yield, although its impact on dysplasia detection needs further study [58]. Table 1 summarizes the performance characteristics of various CCA screening tests in PSC patients.

Table 1. Performance of Screening Tests for Cholangiocarcinoma in PSC

| Test | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA19-9 [38] | 79 | 98 | 56 | 99 |

| Ultrasound [39] | 57 | 94 | 48 | 95 |

| CT [39] | 75 | 80 | 38 | 95 |

| MRI [39] | 63 | 79 | 40 | 91 |

| Bile duct brushings [40] | 43 | 97 | 78 | 87 |

| FISH [47] | 68 | 70 | – | – |

| FISH polysomy [47] | 51 | 93 | – | – |

| pCLE [54] | 100 | 61 | 22 | 100 |

| Cholangioscopy [56] | 92 | 93 | 79 | 97 |

| IDUS [55] | 87 | 90 | 70 | 96 |

Table 1: Summary of screening methods for cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) patients, including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) for various diagnostic tests.

Emerging research includes analyzing bile aspirated during ERCP for CCA biomarkers, such as oxidized phospholipids and volatile organic compounds, showing promising clinical utility [59, 60].

Our current practice involves obtaining two sets of brushings during ERCP, one for cytology and one for FISH. Bile aspiration is also performed for ongoing research purposes.

CONCLUSION

Therapeutic endoscopists play a vital and expanding role in the diagnosis and comprehensive management of PSC. As diagnostic and therapeutic techniques continue to advance, their expertise will become even more integral in improving outcomes for patients with this challenging condition.

References

References are identical to the original article and thus are not re-listed here for brevity, but would be included in a final, complete version.