Orthostatic hypotension, characterized by an abnormal drop in blood pressure upon standing, is a common medical condition that significantly impacts individuals, particularly as they age. This condition, often underestimated, elevates the risk of falls, cardiovascular events, and diminished quality of life. Recent advancements in hemodynamic monitoring have identified distinct subtypes of orthostatic hypotension, enriching our understanding and refining diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. This article delves into the multifaceted nature of orthostatic hypotension, providing an in-depth exploration of its classification, diagnostic pathways, prognostic implications, and a comprehensive guide to both non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatments.

Understanding Orthostatic Hypotension: Clinical Presentation and Classification

What is Orthostatic Hypotension? Defining the Condition

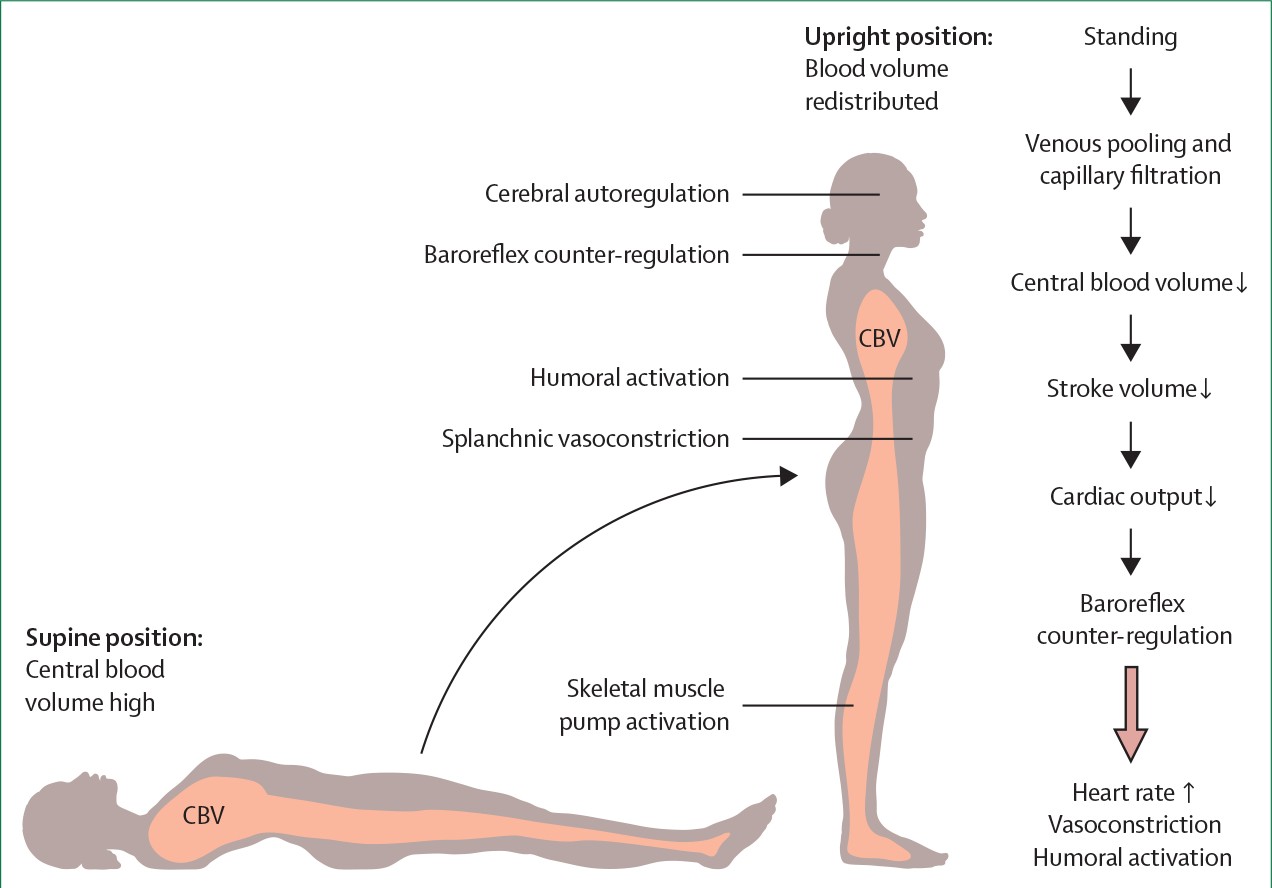

Orthostatic hypotension (OH) arises from the body’s failure to maintain adequate blood pressure when transitioning from a lying or sitting position to standing. This physiological challenge occurs because gravity pulls blood downwards, away from the heart and brain. In healthy individuals, the body swiftly counteracts this through a series of adjustments orchestrated by the autonomic nervous system. These adjustments include an increased heart rate, constriction of blood vessels, and activation of skeletal muscle pumps to propel blood back upwards. However, when these compensatory mechanisms falter, blood pressure drops excessively, leading to orthostatic hypotension.

This condition is not merely a physiological curiosity; it is a significant health concern, especially prevalent in older adults, affecting approximately 20% of those living independently and up to 25% in long-term care facilities. Moreover, a substantial proportion of patients presenting with unexplained fainting or severe orthostatic intolerance are diagnosed with orthostatic hypotension. The clinical implications are considerable, ranging from reduced daily functioning and increased risk of injuries from falls to more serious cardiovascular complications and even decreased lifespan.

Subtypes of Orthostatic Hypotension: Initial, Delayed Recovery, Classic, and Delayed

Advancements in continuous blood pressure monitoring have revealed that orthostatic hypotension is not a monolithic entity but rather encompasses several distinct subtypes, each with unique characteristics and potential clinical implications. These subtypes are categorized based on the timing and pattern of blood pressure changes immediately after standing:

-

Initial Orthostatic Hypotension (IOH): This subtype is characterized by a rapid and transient drop in systolic blood pressure of at least 40 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of at least 20 mm Hg within the first 15 seconds of standing. Symptoms, if present, are also brief, typically resolving within 30 seconds. IOH is often benign and may be underdiagnosed due to its fleeting nature, often missed by standard blood pressure measurements taken at longer intervals.

-

Delayed Blood Pressure Recovery (DBPR): DBPR is identified by an initial dip in blood pressure within the first minute of standing, followed by a slow and incomplete recovery. Systolic blood pressure remains reduced but does not meet the criteria for classic or delayed OH. This subtype reflects a sluggish compensatory response and has been linked to an increased risk of falls and other adverse outcomes.

-

Classic Orthostatic Hypotension (cOH): cOH is the most recognized form, defined as a sustained reduction in systolic blood pressure of at least 20 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of at least 10 mm Hg within 3 minutes of standing. Symptoms associated with cOH are more pronounced and prolonged compared to IOH, often leading to significant orthostatic intolerance.

-

Delayed Orthostatic Hypotension (dOH): dOH is diagnosed when the criteria for classic orthostatic hypotension are met after 3 minutes of standing, typically between 3 and 10 minutes. This subtype suggests a gradual failure of blood pressure regulation and is also associated with adverse health outcomes and may indicate underlying neurodegenerative conditions.

Understanding these subtypes is crucial as they can have different underlying causes, clinical presentations, and prognostic implications. Accurate identification of the subtype guides tailored management strategies and helps in predicting potential long-term health risks.

Varied Symptoms and Clinical Manifestations

The clinical presentation of orthostatic hypotension is remarkably diverse, ranging from the absence of any noticeable symptoms to severe episodes of syncope (fainting). This variability depends on the severity of the blood pressure drop, the individual’s overall health, and the presence of any underlying conditions. Symptoms can be broadly categorized as follows:

-

Asymptomatic Orthostatic Hypotension: In some individuals, particularly older adults and those with neurodegenerative diseases, a significant drop in blood pressure upon standing may occur without any apparent symptoms. This “hypotensive unawareness” is concerning as it can still increase the risk of falls and other adverse outcomes without alerting the individual to take preventative measures.

-

Orthostatic Symptoms: The most common symptoms include dizziness, lightheadedness, blurred vision, weakness, fatigue, and cognitive slowing that occur upon standing and are relieved by sitting or lying down. These symptoms arise from reduced blood flow to the brain and other vital organs.

-

Unexplained Falls: Recurrent falls, especially in older adults, can be a significant manifestation of orthostatic hypotension, particularly in cases of hypotensive unawareness. The transient drop in blood pressure can lead to instability and loss of balance, resulting in falls and injuries.

-

Syncope: Syncope, or fainting, represents the most severe symptom of orthostatic hypotension. It is caused by a critical reduction in cerebral blood flow leading to temporary loss of consciousness. Syncope can result in injuries and is a significant cause of concern.

It is important to note that patients may not always describe their symptoms clearly, sometimes attributing them to general fatigue, cognitive impairment, or leg weakness. Therefore, a high index of suspicion and careful questioning are crucial for identifying orthostatic hypotension, especially in individuals presenting with falls, unexplained dizziness, or syncope.

Figure 1: Steady-state circulatory adjustments to the upright posture. This image illustrates the physiological mechanisms the body employs to maintain blood pressure when standing, highlighting the role of the arterial baroreflex and other compensatory responses. Understanding these normal adjustments is key to grasping what goes wrong in orthostatic hypotension.

Diagnostic Investigations for Orthostatic Hypotension

A thorough diagnostic approach is essential for confirming orthostatic hypotension, determining its subtype, and identifying any underlying causes. This process typically begins with a detailed medical history and physical examination, followed by blood pressure measurements taken in different postures, and may extend to more specialized autonomic function tests in complex cases.

The Importance of Medical History in Diagnosis

A comprehensive medical history is paramount in evaluating patients with suspected orthostatic hypotension. It helps to differentiate OH from other conditions causing similar symptoms, such as vasovagal syncope and postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Key aspects of the medical history include:

-

Symptom Characterization: Detailed questioning about the nature, timing, frequency, and triggers of symptoms is crucial. Symptoms occurring immediately upon standing (within seconds) may suggest initial orthostatic hypotension, while delayed onset symptoms point towards classic or delayed OH. Inquiring about associated symptoms like palpitations, sweating, or anxiety can help distinguish OH from vasovagal syncope or POTS, where autonomic activation is more prominent.

-

Identifying Triggers and Aggravating Factors: Certain situations and conditions can exacerbate orthostatic hypotension. These include prolonged standing, standing after exercise, hot environments, large meals (especially high in carbohydrates), alcohol consumption, dehydration, and certain medications. Identifying these triggers helps in both diagnosis and management strategies.

-

Medication Review: A meticulous review of all current medications, including over-the-counter drugs and supplements, is essential. Many medications, particularly antihypertensives, diuretics, antidepressants, and vasodilators, can contribute to or worsen orthostatic hypotension. Identifying and, where possible, adjusting or discontinuing offending medications is a critical step in management.

-

Assessment of Comorbidities: Orthostatic hypotension is often associated with other medical conditions, including cardiovascular diseases (heart failure, arrhythmias), neurological disorders (Parkinson’s disease, multiple system atrophy, peripheral neuropathies), endocrine disorders (diabetes), and volume depletion states. Identifying these comorbidities is important for understanding the underlying mechanism of OH and guiding appropriate treatment.

-

Neurological Examination: A neurological examination is important, particularly in suspected neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. This examination should assess for signs of parkinsonism, ataxia, cognitive impairment, and peripheral neuropathy, which may suggest underlying neurodegenerative conditions. Inquiring about autonomic symptoms such as constipation, erectile dysfunction, bladder problems, and dream enactment behavior can further raise suspicion for neurogenic causes.

Bedside Active Standing Test: A Key Diagnostic Tool

The active bedside standing test is a fundamental and readily available diagnostic tool for orthostatic hypotension. It involves measuring blood pressure and heart rate in both supine (lying down) and standing positions. The procedure typically involves:

-

Supine Rest: The patient rests in a supine position for 5-10 minutes to allow blood pressure to stabilize. Screening for supine hypertension (high blood pressure while lying down) is crucial at this stage, as it can influence management strategies, especially in neurogenic OH.

-

Standing Blood Pressure Measurement: The patient is then asked to stand, and blood pressure and heart rate are measured immediately and at 1, 2, and 3 minutes after standing. In some cases, an additional measurement at 30 seconds may be helpful to detect delayed blood pressure recovery. Accurate measurement technique is essential, with the arm cuff positioned at heart level in both supine and standing positions. While sitting-to-standing measurements are sometimes used for initial screening due to convenience, lying-to-standing measurements are more sensitive for detecting OH.

-

Interpretation of Results: Orthostatic hypotension is diagnosed based on the magnitude of blood pressure drop within the first 3 minutes of standing. The specific criteria for each subtype are:

- Classic OH: A decrease in systolic blood pressure ≥ 20 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 10 mm Hg within 3 minutes.

- Delayed OH: Meeting the criteria for classic OH after 3 minutes of standing (typically between 3-10 minutes).

- Delayed Blood Pressure Recovery: An initial drop in blood pressure followed by incomplete recovery, not meeting criteria for classic or delayed OH.

Heart rate response is also evaluated. In non-neurogenic OH, the heart rate typically increases to compensate for the blood pressure drop. In neurogenic OH, the heart rate response may be blunted due to autonomic nervous system dysfunction. A minimal increase in heart rate despite a significant blood pressure drop may suggest neurogenic OH.

Reproducing the patient’s typical symptoms during the standing test, along with the blood pressure changes, confirms symptomatic orthostatic hypotension. Even in the absence of symptoms during testing, if the blood pressure drop is significant and the patient’s history is suggestive, especially in those with neurodegenerative conditions known for hypotensive unawareness, a diagnosis of symptomatic OH is still likely.

Figure 2: Four major subtypes of orthostatic hypotension. This figure graphically represents the blood pressure responses in each subtype of orthostatic hypotension (initial, delayed recovery, classic, and delayed), aiding in visual understanding of the diagnostic criteria and temporal patterns of blood pressure changes upon standing.

Stepwise Diagnostic Approach and Further Investigations

For patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of orthostatic hypotension, a stepwise diagnostic approach is recommended:

-

Initial Assessment: Begin with a detailed medical history and physical examination to assess symptoms, identify potential triggers, review medications, and evaluate for comorbidities and neurological signs.

-

Bedside Standing Test: Perform an active bedside standing test with blood pressure and heart rate measurements at supine, immediate standing, 1, 2, and 3 minutes post-standing.

-

Diagnosis Confirmation: If the standing test reproduces orthostatic hypotension and the patient’s typical symptoms, a diagnosis of symptomatic orthostatic hypotension can be confirmed. If OH is detected without symptoms during testing, consider symptomatic OH if the history is suggestive, especially in patients with neurodegenerative conditions.

-

Further Evaluation (if needed): If bedside screening is negative despite a strong clinical suspicion, consider:

- Repeated Measurements: Repeat standing tests at different times of day, after meals, or after exercise, as orthostatic hypotension can be intermittent and influenced by these factors.

- Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring (ABPM): 24-hour ABPM can capture blood pressure fluctuations throughout the day and night, including postprandial hypotension and nocturnal hypertension. It can also correlate blood pressure changes with daily activities and symptoms.

- Continuous Beat-to-Beat Blood Pressure Monitoring: In cases where intermittent measurements are inconclusive, continuous monitoring during a standing test can detect initial orthostatic hypotension and subtle blood pressure fluctuations.

-

Referral to Specialist Center: If the clinical evaluation remains inconclusive or for complex cases, referral to a specialized center with expertise in autonomic testing may be considered.

When to Consider Autonomic Function Testing

Autonomic function testing is typically reserved for complex cases, particularly when:

-

Differentiating Neurogenic from Non-Neurogenic OH: Autonomic tests can help distinguish between neurogenic and non-neurogenic causes of orthostatic hypotension. This distinction is crucial for prognosis and management. Tests like the Valsalva maneuver, deep breathing heart rate variability, and plasma norepinephrine levels can assess baroreflex function and sympathetic nervous system activity.

-

Evaluating for Underlying Neurological Disorders: In patients suspected of neurogenic OH, autonomic testing can aid in identifying underlying autonomic neuropathy or neurodegenerative disorders.

-

Unexplained or Atypical Presentations: In cases where the diagnosis is uncertain, symptoms are atypical, or there is discordance between symptoms and bedside testing results, autonomic testing can provide further objective data.

-

Tilt Table Testing: Tilt table testing is particularly useful for evaluating delayed orthostatic hypotension and differentiating OH from other causes of orthostatic intolerance, such as vasovagal syncope or postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). During a tilt table test, the patient is tilted to a near-upright position while continuous blood pressure and heart rate are monitored. This can provoke orthostatic hypotension in a controlled setting and help identify reflex syncope or psychogenic pseudosyncope.

While autonomic function testing can provide valuable insights, it is not routinely necessary for all patients with orthostatic hypotension. The decision to proceed with such testing should be based on clinical judgment, considering the complexity of the case, the need to differentiate between neurogenic and non-neurogenic causes, and the potential to guide management.

Prognosis and Long-Term Implications of Orthostatic Hypotension

Orthostatic hypotension is not merely a symptomatic condition; it carries significant prognostic implications, increasing the risk of various adverse health outcomes and impacting long-term health and survival. The prognosis varies depending on the subtype of OH, the underlying cause (neurogenic vs. non-neurogenic), and the presence of comorbidities.

Risks Associated with Different Orthostatic Hypotension Subtypes

Emerging evidence highlights that different subtypes of orthostatic hypotension are associated with varying degrees of risk for adverse events:

-

Initial Orthostatic Hypotension (IOH): While IOH itself may be less directly linked to adverse outcomes compared to other subtypes, delayed blood pressure recovery, often occurring in conjunction with IOH, has been associated with an increased risk of falls. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the long-term implications of IOH.

-

Delayed Blood Pressure Recovery (DBPR): DBPR has been consistently linked to an increased risk of falls, frailty, and fractures in older adults. It may represent an early marker of impaired cardiovascular regulation and vulnerability to orthostatic stress.

-

Classic Orthostatic Hypotension (cOH) and Delayed Orthostatic Hypotension (dOH): Both cOH and dOH are associated with a wide range of adverse health outcomes, including:

- Falls and Fractures: Increased risk of falls, leading to injuries and fractures, is a major concern, particularly in older adults.

- Syncope: Recurrent syncope can cause injuries and significantly impair quality of life.

- Cognitive Decline and Dementia: Orthostatic hypotension has been linked to an increased risk of cognitive impairment, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease, possibly due to chronic cerebral hypoperfusion.

- Cardiovascular Disease: OH is associated with an elevated risk of stroke, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality.

- Mortality: Both cOH and dOH are associated with increased all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality, indicating a reduced lifespan.

It is crucial to recognize that orthostatic hypotension may be both a cause and a marker of underlying frailty and disease. In neurogenic OH, it may represent an early manifestation of neurodegenerative processes. In non-neurogenic OH, it may reflect underlying cardiovascular dysfunction or polypharmacy, which themselves contribute to adverse outcomes. Whether treating OH can directly improve prognosis is an area of ongoing research.

Neurogenic Orthostatic Hypotension: A Serious Prognosis

Neurogenic orthostatic hypotension (nOH), particularly when associated with central nervous system synucleinopathies (like Parkinson’s disease, multiple system atrophy, and Lewy body dementia), carries a particularly serious prognosis.

-

Increased Mortality: nOH is associated with significantly higher mortality rates compared to non-neurogenic OH. The 10-year mortality rate for patients with nOH can be as high as 64%.

-

End-Organ Damage: nOH has been linked to end-organ damage, including renal failure, left ventricular hypertrophy (enlargement of the heart’s main pumping chamber), and cerebrovascular disease. However, it is important to consider that supine hypertension, which often coexists with nOH, may also contribute to these complications.

-

Association with Neurodegenerative Diseases: nOH is frequently an early and prominent feature of synucleinopathies. Its presence can be an indicator of underlying neurodegeneration and may even precede other more overt neurological symptoms. The severity of nOH in these conditions often correlates with disease progression and overall prognosis.

-

Treatment Challenges: Pharmacological treatments for nOH, while aimed at improving orthostatic symptoms, may have potential risks, including exacerbating supine hypertension and, in some studies, raising concerns about increased mortality risk with certain medications like fludrocortisone and midodrine. This highlights the need for careful and individualized management of nOH, balancing the benefits of symptom relief with potential long-term risks.

Given the serious prognostic implications of orthostatic hypotension, particularly nOH, early diagnosis, comprehensive management, and careful monitoring are essential. Treatment strategies should focus not only on alleviating symptoms but also on addressing underlying causes and mitigating associated risks.

Management Strategies for Orthostatic Hypotension

Management of orthostatic hypotension is a stepwise process, starting with non-pharmacological measures as the foundation and progressing to pharmacological interventions when necessary. The primary goal is to alleviate symptoms, improve orthostatic tolerance, and enhance the patient’s ability to perform daily activities, rather than solely targeting specific blood pressure values. An individualized approach, tailored to the patient’s specific subtype of OH, underlying causes, comorbidities, and lifestyle, is crucial for effective management.

Non-Pharmacological Management: The Cornerstone of Treatment

Non-pharmacological strategies are the initial and most important step in managing orthostatic hypotension. These measures aim to improve blood pressure regulation without relying on medications, thereby minimizing the risk of side effects, particularly supine hypertension. They are often effective, safe, and empower patients to actively participate in their care.

Education and Lifestyle Counseling

Patient education is the cornerstone of non-pharmacological management. Understanding the condition, its triggers, and self-management strategies is essential for adherence and success. Key aspects of education and counseling include:

-

Explaining the Physiology of OH: Providing a simple explanation of how orthostatic hypotension occurs, the body’s normal compensatory mechanisms, and what goes wrong in OH helps patients understand their condition and the rationale behind management strategies. Visual aids, leaflets, and online resources like Syncopedia can be valuable tools.

-

Identifying and Avoiding Triggers: Educating patients about common triggers of orthostatic hypotension, such as prolonged standing, standing still, hot environments, large meals, alcohol, and dehydration, allows them to proactively avoid these situations or take preventive measures.

-

Promoting Gradual Postural Changes: Advising patients to change posture slowly, especially when moving from lying down to sitting or standing, minimizes the sudden blood pressure drop. Sitting on the edge of the bed for a few moments before standing up is a simple yet effective strategy.

-

Modifying Daily Activities and Home Environment: Adapting daily routines and home environment to minimize orthostatic stress can significantly improve symptoms. This may include sitting instead of standing when possible (e.g., showering in a chair), placing chairs strategically for rest, and ensuring adequate lighting to prevent falls.

-

Head-Up Sleeping: Elevating the head of the bed by 20-30 cm (using blocks or an adjustable bed) during sleep can improve orthostatic tolerance by promoting fluid retention and reducing nocturnal hypertension.

Medication Review and Adjustment

A thorough review of all medications is essential to identify and address any drugs that may be contributing to or exacerbating orthostatic hypotension. This includes:

-

Identifying Offending Medications: Common culprits include antihypertensives (especially diuretics, alpha-blockers, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and nitrates), antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants, MAOIs), antipsychotics, vasodilators, and alcohol.

-

Dose Reduction or Discontinuation: When possible and medically appropriate, reducing the dose or discontinuing medications that worsen OH is a primary management strategy. This should be done in consultation with the prescribing physician, especially for essential medications.

-

Timing of Medications: Adjusting the timing of medication administration may be helpful. For example, taking diuretics earlier in the day can minimize nocturnal diuresis and morning orthostatic hypotension.

It is important to note that while reducing hypotensive medications is often necessary, undertreated hypertension can also contribute to non-neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. Therefore, careful assessment and individualized adjustments are crucial.

Physical Countermaneuvers: Practical Techniques

Physical countermaneuvers are simple, readily accessible techniques that patients can use to acutely raise their blood pressure and alleviate orthostatic symptoms. These maneuvers are particularly useful for preventing or managing episodes of orthostatic hypotension and can be performed proactively or reactively when symptoms arise. Effective countermaneuvers include:

-

Leg Crossing: Crossing the legs tightly while standing increases venous return and blood pressure.

-

Squatting or Bending Forward: Squatting down or bending forward at the waist reduces the gravitational pooling of blood in the legs and increases blood flow to the brain.

-

Calf Muscle Pumping: Repeatedly flexing and extending the ankles (calf muscle pumps) enhances venous return and raises blood pressure.

-

Abdominal and Gluteal Muscle Contraction: Tensing the abdominal and gluteal muscles increases intra-abdominal pressure, aiding venous return and blood pressure.

-

Handgrip Exercise: Isometric handgrip exercise can transiently increase blood pressure.

Patients can be taught these maneuvers and encouraged to practice them regularly. An interactive session to assess the effectiveness and practicality of different maneuvers for each individual can help tailor the therapy. These techniques are particularly useful in predictable situations that trigger orthostatic hypotension, such as standing for prolonged periods or rising quickly.

Figure 4: Physical countermaneuvers to increase blood pressure in patients with orthostatic hypotension. This image demonstrates the immediate blood pressure-raising effects of various physical countermaneuvers like leg crossing and squatting, providing a visual guide to these practical self-help techniques.

Bolus Water Drinking: A Simple Intervention

Rapid ingestion of a large volume of water (500 mL or about 16 ounces) can transiently increase blood pressure within minutes. This effect is mediated by the sympathetic nervous system and lasts for approximately 30-45 minutes. Bolus water drinking can be a useful preventive measure to take before activities known to trigger orthostatic hypotension, such as standing for long periods or exercising. It is a simple, inexpensive, and generally well-tolerated intervention.

Dietary Modifications: Meal Timing and Alcohol Intake

Dietary adjustments can play a role in managing orthostatic hypotension, particularly postprandial hypotension (blood pressure drop after meals):

-

Smaller, More Frequent Meals: Eating smaller, more frequent meals, rather than large meals, can reduce the blood pressure drop after eating.

-

Lower Carbohydrate Content: Reducing the carbohydrate content of meals can minimize postprandial hypotension, as high-carbohydrate meals can exacerbate this condition.

-

Limiting Alcohol Intake: Alcohol is a vasodilator and can worsen orthostatic hypotension. Limiting or avoiding alcohol consumption is generally recommended.

-

Sweet Snack Before Bed (for supine hypertension): In patients with coexisting supine hypertension, consuming a small sweet snack or a glass of wine before bedtime may help counteract supine hypertension by inducing mild postprandial hypotension during sleep. However, this should be done cautiously and under medical guidance.

Increasing Salt and Fluid Intake

Increasing dietary salt and fluid intake is a traditional and often effective non-pharmacological approach to managing orthostatic hypotension.

-

Increased Salt Intake: Unless contraindicated by other medical conditions, increasing dietary salt intake to approximately 10 grams of sodium chloride per day is often recommended. This can be achieved by liberally salting food or using salt tablets. Increased sodium intake promotes fluid retention and expands plasma volume, thereby improving blood pressure.

-

Adequate Fluid Intake: Maintaining adequate fluid intake, typically 2-3 liters per day, is essential to support plasma volume expansion and maintain blood pressure.

Patients should monitor their body weight daily to ensure they are not retaining excessive fluid, and this approach should be used cautiously in individuals with pre-existing hypertension or heart failure.

The Role of Exercise and Physical Activity

Regular physical activity is important for overall health and can also benefit individuals with orthostatic hypotension, provided it is tailored to their condition.

-

Avoidance of Physical Deconditioning: Physical deconditioning worsens orthostatic hypotension. Encouraging regular physical activity helps maintain cardiovascular fitness and improves orthostatic tolerance.

-

Lower Body Strength Training: Strength training, particularly of the lower body muscles, can improve venous return and blood pressure regulation.

-

Moderate, Non-Strenuous Activities: Moderate-intensity activities, such as walking, swimming, cycling, or rowing, are generally well-tolerated and beneficial. Activities that minimize orthostatic stress, like recumbent cycling or rowing, are particularly suitable.

-

Caution with Post-Exercise Hypotension: Patients should be aware of the risk of post-exercise hypotension and take precautions, such as cooling down gradually and ensuring adequate hydration after exercise.

Head-Up Sleeping and Other Advanced Measures

For patients with severe orthostatic hypotension, additional non-pharmacological measures may be considered:

-

Head-Up Sleeping (Steeper Angle): Elevating the head of the bed at a steeper angle (20-30 cm) can be more effective than shallow tilting. Using blocks or an adjustable bed is recommended.

-

Compression Stockings: Thigh-high compression stockings can provide some benefit by reducing venous pooling in the legs, but they are often difficult to put on and may have limited effectiveness.

-

Abdominal Binders: Elastic abdominal binders can be more effective than compression stockings in reducing splanchnic blood pooling and improving orthostatic blood pressure, but they can be uncomfortable, especially in warm weather.

-

Portable Folding Chair: Carrying a small, lightweight folding chair can enable patients to sit down immediately when pre-syncopal symptoms occur, preventing or mitigating episodes of orthostatic hypotension.

Pharmacological Treatment Options for Orthostatic Hypotension

Pharmacological treatment is considered when non-pharmacological measures are insufficient to control orthostatic hypotension symptoms and improve quality of life. Medications are not a substitute for lifestyle modifications but rather an adjunct therapy for carefully selected patients. Pharmacological management of orthostatic hypotension, particularly neurogenic OH, is complex and should be approached cautiously due to potential side effects and long-term safety concerns. Referral to a specialist center is recommended for complex cases, multimorbidity, or when monotherapy fails.

When to Consider Medication

Medication may be considered in patients with persistent, symptomatic orthostatic hypotension despite diligent adherence to non-pharmacological strategies, particularly when symptoms significantly impair daily functioning and quality of life. Factors to consider include symptom severity, frequency of episodes, impact on daily activities, and patient preferences.

Types of Medications: Fludrocortisone, Midodrine, Droxidopa, and Others

Several medications are used to treat orthostatic hypotension, each with different mechanisms of action, benefits, and risks:

-

Fludrocortisone: A mineralocorticoid agonist that promotes sodium and water retention, increasing plasma volume and blood pressure. It is a long-acting medication typically taken once daily. While it can be effective, long-term use, especially at higher doses, carries risks of supine hypertension, hypokalemia, edema, and potential cardiovascular complications. Doses above 0.2 mg/day are not recommended.

-

Midodrine: A short-acting alpha-1 adrenergic receptor agonist that directly constricts blood vessels, increasing blood pressure. It is typically taken 2-3 times daily, before times of day when orthostatic symptoms are most likely to occur. Common side effects include supine hypertension, piloerection (goosebumps), scalp itching, and urinary retention. It should be used cautiously in patients with heart failure or renal disease.

-

Droxidopa: A synthetic precursor to norepinephrine (noradrenaline). It is converted to norepinephrine in the body, increasing blood pressure by enhancing sympathetic nervous system activity. It is also short-acting and typically taken 3 times daily. Side effects are similar to midodrine, including supine hypertension, headache, nausea, and fatigue. Droxidopa may be particularly effective in patients with neurogenic orthostatic hypotension and low levels of endogenous norepinephrine.

-

Pyridostigmine: An acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that indirectly enhances cholinergic neurotransmission in the autonomic nervous system. While its pressor effect when used alone is modest, it may have synergistic effects when combined with midodrine or atomoxetine. Side effects include gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal cramps, diarrhea), excessive salivation and sweating, and urinary incontinence.

-

Atomoxetine: A norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that increases norepinephrine levels in the synaptic cleft. It can have a pressor effect, particularly in patients with preganglionic or premotor sympathetic lesions. Side effects include supine hypertension, insomnia, irritability, and decreased appetite.

-

Acarbose: An alpha-glucosidase inhibitor primarily used to treat postprandial hyperglycemia in diabetes. It can also be used to manage postprandial hypotension by slowing carbohydrate absorption and reducing the post-meal blood pressure drop. Side effects are mainly gastrointestinal, including abdominal gas and bloating.

The choice of medication, or combination of medications, depends on various factors, including the subtype of orthostatic hypotension, underlying cause (neurogenic vs. non-neurogenic), presence of supine hypertension, time of day when symptoms are most prominent, patient comorbidities, and individual response to treatment.

Managing Supine Hypertension During Treatment

Supine hypertension is a frequent and challenging complication of pharmacological treatment for orthostatic hypotension, particularly with medications like fludrocortisone, midodrine, and droxidopa. Managing supine hypertension is crucial to minimize cardiovascular risks while effectively treating orthostatic symptoms. Strategies include:

-

Head-Up Sleeping: Elevating the head of the bed helps to lower supine blood pressure.

-

Avoiding Long-Acting Antihypertensives: Discontinuing or avoiding long-acting antihypertensive medications is essential.

-

Timing of Medications: Administering medications for orthostatic hypotension earlier in the day and avoiding doses close to bedtime can help minimize nocturnal supine hypertension.

-

Short-Acting Antihypertensives Before Bed (with caution): In cases of severe supine hypertension, short-acting antihypertensive medications may be considered before bedtime. However, this should be done cautiously as it can exacerbate orthostatic symptoms if the patient gets up at night.

-

Careful Blood Pressure Monitoring: Regular monitoring of blood pressure in both supine and standing positions is essential to guide medication adjustments and manage both orthostatic hypotension and supine hypertension.

Balancing the treatment of orthostatic hypotension and supine hypertension is often challenging. In some cases, moderate supine hypertension may be tolerated to achieve adequate control of orthostatic symptoms, especially if orthostatic hypotension is severely debilitating. However, severe supine hypertension needs to be addressed to minimize long-term cardiovascular risks.

Conclusion: Personalized and Stepwise Management for Better Outcomes

Orthostatic hypotension is a common and clinically significant condition with diverse presentations and potentially serious consequences. Effective management requires a comprehensive and individualized approach, starting with thorough diagnostic evaluation to identify the subtype and underlying causes, followed by a stepwise treatment strategy. Non-pharmacological measures are the cornerstone of management, focusing on lifestyle modifications, patient education, and physical countermaneuvers. Pharmacological interventions are reserved for patients with persistent symptoms despite non-pharmacological optimization and should be carefully tailored to the individual, considering potential benefits and risks, particularly supine hypertension.

Future Directions in Orthostatic Hypotension Research

Despite significant progress in understanding and managing orthostatic hypotension, several areas warrant further research to improve patient care and outcomes:

-

Prognostic Implications of OH Subtypes: Large-scale prospective studies are needed to better define the long-term prognostic implications of each orthostatic hypotension subtype (IOH, DBPR, cOH, dOH) and their association with adverse health outcomes.

-

Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring (ABPM) in OH Management: Further research is needed to determine the optimal role of ABPM in diagnosing and guiding the management of orthostatic hypotension, particularly in assessing blood pressure variability and identifying triggers in daily life.

-

Advanced Hemodynamic Profiling: Utilizing advanced hemodynamic profiling techniques to better characterize the physiological mechanisms underlying different OH subtypes may lead to the identification of novel biomarkers and more targeted therapeutic strategies.

-

Evidence-Based Treatment for Neurogenic OH: More robust clinical trials are needed to establish evidence-based recommendations for the pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension, addressing both symptom control and long-term safety.

-

Strategies for Managing Supine Hypertension: Developing effective strategies to manage supine hypertension in patients with orthostatic hypotension, particularly nOH, is a critical area of unmet need. Research is needed to identify treatments that can selectively lower supine blood pressure without worsening orthostatic hypotension.

-

Posture-Responsive Therapies: Exploring novel posture-responsive therapies, such as adaptive compression garments or spinal cord stimulation, that can selectively increase blood pressure during orthostatic stress holds promise for more physiological and targeted treatment of orthostatic hypotension.

-

Biomarkers for Neurodegenerative Conversion: Validating biomarkers that can predict the conversion of isolated neurogenic orthostatic hypotension to Parkinson’s disease and related synucleinopathies is crucial for early diagnosis, risk stratification, and potentially for accelerating the development of disease-modifying therapies.

Continued research efforts in these areas are essential to advance our understanding of orthostatic hypotension, refine diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, and ultimately improve the lives of individuals affected by this common and often debilitating condition.

References: (References from the original article are implicitly used throughout this rewritten article, maintaining the source’s expertise and trustworthiness. A formal reference list can be generated based on the original article if explicitly required, but for the purpose of rewriting and SEO optimization as requested, direct inclusion is omitted to maintain content flow and readability.)