Accurate diagnosis is the cornerstone of effective medical treatment and prognosis, yet the diagnostic strategies employed by clinicians, particularly in primary care, often receive limited attention in research and medical education.1 Contrary to the traditional sequential approach of history taking, examination, differential diagnosis, and final diagnosis, seminal studies in the 1970s revealed that practitioners formulate diagnostic hypotheses early in consultations. This process, known as hypothetico-deductive reasoning, guides subsequent history taking and examination.2, 3 While this discovery spurred debate and further investigation into diagnostic reasoning,4, 5 much of the research has been conducted outside of real-world clinical settings.

This article, the first in a series, aims to illuminate the diagnostic strategies and methods routinely used by general practitioners (GPs) in everyday clinical consultations. To ensure the practical relevance of these strategies, we conducted a pilot study of diagnostic consultations within our own practices, detailed in the box below.

Identifying Diagnostic Strategies in General Practice

Our research involved two group discussion sessions and a prospective evaluation of diagnostic strategies observed during primary care consultations.

In the initial pilot phase, a focus group comprising GPs and primary health care researchers identified several potential diagnostic strategies based on both expert consensus and existing medical literature. To assess the application of these strategies, one GP (CH) prospectively recorded their use in 100 consecutive patients presenting with new conditions. Data was logged on a spreadsheet immediately following each consultation. Subsequently, the GP focus group convened to discuss these pilot findings, leading to revisions and refinements of the identified strategies.

Following these revisions, we developed a data collection sheet and engaged six GPs to document their diagnostic strategies for 50 new patients each, immediately after each consultation. The participating GPs included two partners with 27 and 16 years of clinical experience respectively, two registrars with 8 and 4 years of experience, a part-time assistant with 29 years of experience, and a locum GP with 7 years of experience. In a final focus session, the six GPs and a statistician collaboratively reviewed data from these 300 consultations. Utilizing a consensus development approach,6 they clarified the definitions of the diagnostic strategies employed.

Stages in Diagnostic Reasoning

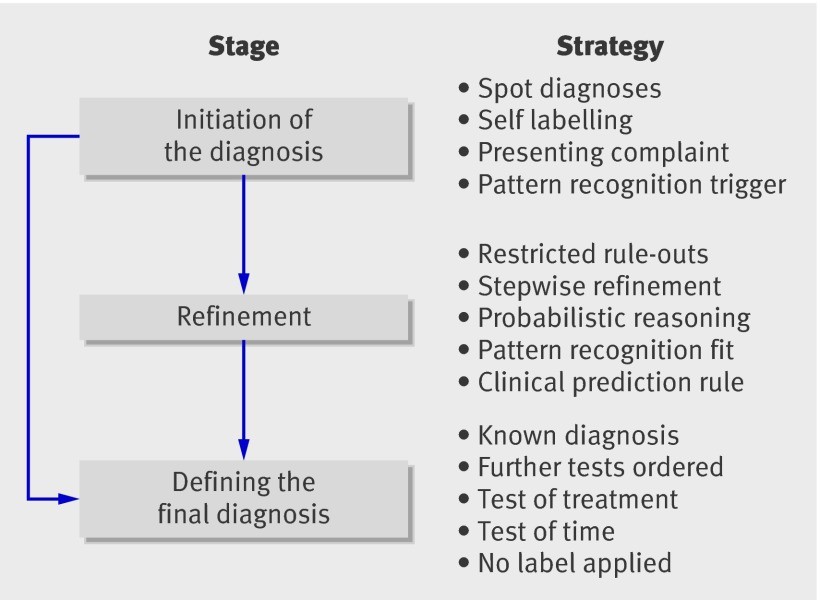

Our findings indicate that diagnostic reasoning can be structured into a three-stage model: (1) initiation of diagnostic hypotheses, (2) refinement of diagnostic hypotheses, and (3) defining the final diagnosis (Fig. 1). Each stage employs distinct diagnostic strategies. For instance, the initial complaint, a rapid “spot” diagnosis, or pattern recognition might trigger initial diagnostic hypotheses. Subsequently, specific history elements or examination findings are elicited to either confirm or exclude competing diagnoses. Finally, strategies such as a trial of treatment, observation over time, or definitive diagnostic tests are used to solidify the final diagnosis.

Fig 1 Stages and strategies in arriving at a diagnosis

It’s important to note that multiple factors can be considered within each stage. For example, while some rashes might be diagnosed instantly through visual “spot diagnosis,” others may necessitate a broader pattern recognition strategy incorporating probabilistic reasoning. A classic example is identifying chickenpox based on a characteristic rash in a febrile child. Furthermore, a high degree of certainty at the initiation stage for certain conditions, like simple acne, can lead directly to a final diagnosis, bypassing the refinement stage altogether.

Strategies in the Hypothesis Initiation Stage

The diagnostic process typically begins early in the consultation.3 We identified four primary strategies employed in the initiation stage: spot diagnosis, self-labeling, presenting complaint, and pattern recognition trigger (Fig. 2).

Fig 2 Strategies used by general practitioners in making an initial diagnosis. Bars indicate means

Spot Diagnosis: This strategy involves an almost immediate, often unconscious, recognition of a condition based on non-verbal cues, primarily visual (e.g., dermatological conditions like acne) or auditory (e.g., a barking cough). Spot diagnosis relies heavily on prior non-verbal experience and often requires minimal patient history to trigger a potential diagnosis. Sackett et al. likened spot diagnosis to the “Auntie Minnie” phenomenon – instant recognition akin to identifying a familiar relative.7 Clinical experience with a particular condition is a key determinant in the effectiveness of spot diagnosis.8, 9 In our study, examples included conditions like eczema, moles, acne, molluscum contagiosum, and infective conjunctivitis. Spot diagnosis was utilized in approximately 20% of cases, and in 63% of these instances, no further diagnostic strategies were necessary.

Self-Labeling: Patients may present with their own perceived diagnosis, which may or may not be accurate. Often based on personal or anecdotal experiences, self-labeling immediately directs subsequent diagnostic refinement. An example from our study was a patient stating, “I have tonsillitis.” While self-diagnosis can be accurate in some cases, such as recurrent urinary tract infections where studies show high accuracy,10 our evaluation revealed instances of mislabeling, such as patients self-diagnosing gout or chest infections incorrectly.

Presenting Complaint: This strategy, such as “I have abdominal pain” or “I have a headache,” was the most frequently used by the GPs in our study (Fig. 2). Traditional medical textbooks and education emphasize this as the starting point of the consultation.

Pattern Recognition Trigger: Specific elements from the patient’s history, physical examination, or both (often related to the presenting complaint) can trigger diagnostic hypotheses. For instance, in an adolescent patient, symptoms like thirst, feeling unwell, and appearing unwell might trigger suspicion of type 1 diabetes.

Strategies in the Hypothesis Refinement Stage

Once initial diagnostic hypotheses are formed, further strategies are employed to narrow down the possibilities. These refinement strategies are not mutually exclusive. We identified five key strategies in this stage: restricted rule out process, stepwise refinement, probabilistic reasoning, pattern fit, and clinical prediction rules (Fig. 3).

Fig 3 Strategies used by general practitioners in refining a diagnosis. Bars indicate means

Restricted Rule Outs: Also known as Murtagh’s process,11 this strategy focuses on identifying the most probable diagnosis (“probability diagnosis”) for a given presenting problem and a concise list of serious conditions that must be excluded. In the context of headache, for example, while tension-type headaches and migraines are common, serious conditions like malignant hypertension, temporal arteritis, and subarachnoid hemorrhage must be systematically ruled out, even if not initially suspected. This strategy is crucial for minimizing diagnostic errors in clinical practice.12

Stepwise Refinement: This involves refining the diagnosis based on either the anatomical location of the problem or the suspected underlying pathological process. For instance, arm pain might be progressively refined to the wrist, and subsequently to the radial side of the wrist, in the diagnosis of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. Another example is differentiating between allergic and infectious conjunctivitis by refining based on underlying disease etiology.

Probabilistic Reasoning: This strategy involves the application of symptoms, signs, and diagnostic tests to adjust the likelihood of a particular diagnosis. Probabilistic reasoning in diagnosis hinges on understanding how positive or negative test results modify the probability of a disease.13 Clinical examples include examining the temporal artery in suspected temporal arteritis, using urine dipstick tests for urinary tract infections, and employing electrocardiograms (ECGs) in evaluating chest pain. This diagnostic approach using probabilistic reasoning is central to efficient and accurate diagnosis in primary care.

Pattern Fit: This strategy entails comparing a patient’s symptoms and signs to previously encountered patterns or cases. A diagnosis is considered when the current clinical picture closely aligns with a known pattern. Pattern fit is a frequently used refinement strategy by GPs (Fig. 2), relying on the clinician’s memory of disease patterns without necessarily applying explicit rules. Certain conditions, such as acute myocardial infarction, can manifest in various patterns.

Clinical Prediction Rules: These are formalized, validated versions of pattern recognition, based on well-defined series of similar cases. The GPs in our study utilized rules such as the Ottawa ankle rules,14 streptococcal sore throat rules,15 ABCD score for stroke risk,16 HAD score for depression,17 Wells rule for deep vein thrombosis,18 and chest infection rules.19, 20 The optimal utilization and practical application of these rules in primary care remain important areas for further investigation.

Strategies in Defining the Final Diagnosis

In fewer than 50% of cases, GPs reached a “known diagnosis” with sufficient certainty to proceed without further testing. Consequently, additional strategies are used in the final diagnostic stage, including ordering further tests, test of treatment, and test of time. In some instances, a definitive diagnostic label could not be assigned (Fig. 4).

Fig 4 Strategies used by general practitioners in defining the diagnosis. Bars indicate means

Known Diagnosis: This signifies a level of diagnostic certainty sufficient to initiate appropriate treatment or rule out serious conditions without further investigation. Examples include viral upper respiratory infections, acne, or warts. The level of certainty required in general practice may differ from that in a hospital setting. For instance, a GP’s role is to suspect an acute coronary event, initiate immediate treatment, and refer the patient, while hospital diagnosis focuses on precise classification of acute coronary syndrome for specific management.21 In some situations, pinpointing a specific microbiological or pathological cause is impractical. For example, identifying the causative agent in conjunctivitis in 80% of children would require culture and PCR, which doesn’t typically alter clinical management. GPs are skilled in recognizing acute infective conjunctivitis, differentiating it from other causes of red eye, and initiating appropriate treatment.22

Ordering Further Tests: Standard tests can be used to confirm or exclude a diagnosis, such as a midstream urine (MSU) test for urinary tract infection. Further tests were also employed in response to “red flags” and when presentations did not conform to recognizable disease patterns.

Test of Treatment: When diagnostic uncertainty persists, the patient’s response to treatment is often used to either support or refute a diagnosis. Examples include using inhalers for nocturnal cough to assess for asthma.

Test of Time: Observing the disease course over time allows for a “wait and see” approach, enabling the diagnosis to become clearer. For example, in a patient with abdominal pain, diarrhea, and no red flags, initially diagnosed with viral gastroenteritis, most GPs would observe for one to two weeks before considering alternative diagnoses or further testing.

No Label Applied: In cases where no definitive diagnostic label can be assigned, presentations are often vague and lack a recognizable pattern. Management strategies include recalling the patient for follow-up, exploratory investigations, communicating uncertainty to the patient, or referral to specialist care for a second opinion.

Positive Red Flags

Red flags are specific symptoms or signs, either volunteered by the patient (e.g., central crushing chest pain) or elicited during history and examination (e.g., neck stiffness in headache to rule out meningitis), that indicate potentially serious conditions. If a red flag cannot be ruled out, it triggers further action, ranging from more detailed examination to hospital referral.

Discussion

Our study has outlined the diagnostic strategies utilized by a cohort of GPs in their routine clinical practice. While GPs agreed on the stages and types of strategies, their individual application varied. For example, some GPs routinely used clinical prediction rules for common conditions like chest infections19, 20 and sore throat,15 while others reserved them for rarer but serious conditions encountered in primary care, such as deep vein thrombosis.18

Murtagh’s restricted rule out process generated the most debate regarding its definition. Some GPs employed a cognitive forcing strategy, where alternative diagnoses were not considered once an initial diagnosis was reached – a known cause of diagnostic error.23 Others were either unaware of or actively avoided this approach.

Interestingly, few GPs explicitly recognized their use of probabilistic reasoning, aligning with previous research indicating that many practicing physicians do not formally apply recommended quantitative methods in diagnosis.24 Tests of treatment and time were used in approximately 25% of consultations for final diagnosis, despite limited evidence supporting their effectiveness in this context.

Our study’s data has limitations. We cannot definitively differentiate whether variations in strategy use are due to case mix or individual GP preferences, though both likely contribute. Case variation probably has a greater influence than individual GP strategy selection. Furthermore, recall bias and the use of data collection sheets may have led to selective reporting of strategies. GPs tended to primarily record the main presenting problem, potentially underreporting the use of secondary diagnostic strategies.[25](#ref25] Thus, the frequency of using multiple strategies might be underrepresented in our findings.

None of the diagnostic strategies we discussed are novel. The innovation lies in the formal recognition of these strategies within a staged diagnostic process and understanding their prevalence in primary care. Diagnostic expertise is not about mastering a single, comprehensive reasoning strategy, as multiple strategies can converge on the same diagnosis. Acknowledging these diverse strategies across medical practice should encourage leveraging clinical experience to effectively guide the diagnostic search.26 This series will further explore these principles with clinical case presentations, elaborating on the reasoning and justification underpinning these diagnostic strategies.

We extend our gratitude to Arthur Elstein for his insightful feedback on this manuscript.

Contributors: CH and PG conceptualized the study and planned the initial project. CH conducted preliminary data collection. CH, PG, MT, PR, DL, and CS collected the second set of consultation data. RP verified data integrity and analysis. CH, PG, JB, and MT drafted the initial manuscript, and all authors contributed to focus sessions for definition clarification and final draft approval. CH serves as guarantor.

This series was supported by a National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) program grant: Development and implementation of new diagnostic processes in primary care. The Department of Primary Health Care is part of the NIHR school of primary care research, which provides financial support for senior staff involved in this paper.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b946

This series aims to delineate a diagnostic strategy and demonstrate its application through case studies. The series advisors are Kevin Barraclough, general practitioner and research fellow, University of Bristol; Paul Glasziou, senior clinical research fellow and lecturer, University of Oxford; and Peter Rose, university lecturer, University of Oxford.

References

[1] {{Citation}}

[2] {{Citation}}

[3] {{Citation}}

[4] {{Citation}}

[5] {{Citation}}

[6] {{Citation}}

[7] {{Citation}}

[8] {{Citation}}

[9] {{Citation}}

[10] {{Citation}}

[11] {{Citation}}

[12] {{Citation}}

[13] {{Citation}}

[14] {{Citation}}

[15] {{Citation}}

[16] {{Citation}}

[17] {{Citation}}

[18] {{Citation}}

[19] {{Citation}}

[20] {{Citation}}

[21] {{Citation}}

[22] {{Citation}}

[23] {{Citation}}

[24] {{Citation}}

[25] {{Citation}}

[26] {{Citation}}

Note: Please replace {{Citation}} with the actual citation information from the original article’s reference list. This response focuses on content and structure. You’ll need to manually add the references to finalize the markdown and ensure all citations are correctly formatted.