Abstract

Achieving equity in healthcare necessitates a deep understanding of the factors that contribute to disparities. This study employed a sequential, mixed-methods approach to investigate child, family, and organizational factors impacting wait times for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnostic evaluations. We analyzed data from 353 families scheduled for evaluations in English and Spanish (27% Spanish). Focus groups with parents and caregivers in both languages provided valuable insights into their experiences with the diagnostic process. Our findings revealed that Diagnosis In Spanish was associated with higher evaluation completion rates and longer wait times compared to English. Notably, appointment availability emerged as the key organizational factor mediating time-to-evaluation. Qualitative data highlighted potential reasons for the higher completion rates among Spanish-speaking families, such as limited alternative diagnostic resources in their communities. This case study underscores the critical role of organizational-level factors in creating delays and disparities in accessing childhood health and mental health services. We discuss strategies applicable across healthcare settings to promote equitable access to diagnostic and intervention services for all children.

Keywords: appointment availability, autism, health disparity, organizational factors, diagnosis in spanish

Culturally responsive care is essential in mental health services, extending beyond individual and family interactions to encompass organizational factors. Disparities in access, delivery, and quality of mental health services are often influenced by organizational structures. In the context of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), significant racial and ethnic disparities in diagnosis rates and age have been well-documented (Daniels & Mandell, 2014; Shattuck et al., 2009). Organizational factors are recognized as contributors to these persistent inequalities (Smith et al., 2020). Prompt diagnosis in spanish or English is crucial as it facilitates timely access to evidence-based interventions, optimizing children’s development and enhancing caregiver well-being by reducing family stress (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2015). Previous research on ASD diagnostic service access has predominantly focused on child- and family-level factors associated with diagnostic delays. These factors include racial or ethnic minority status, limited English proficiency among caregivers, immigrant status, and low household income (Daniels & Mandell, 2014; Valicenti-McDermott et al., 2012). While policy-level factors and healthcare systems contribute to these disparities, less attention has been paid to organizational factors within clinics that can be modified, such as the availability of services in a family’s preferred language (Daniels & Mandell, 2014; Zuckerman, Sinche, Cobian, et al., 2014).

In the United States, a significant proportion of children (5.7%) live in households where adults have limited English proficiency (Kids Data, 2018). Given the crucial role of caregivers in accessing mental health and neurodevelopmental services for children, linguistic accessibility is paramount (Yun, Jenicek, & Gerdes, 2019). Addressing household language is thus essential for improving access to services, including diagnosis in spanish and English for ASD in early childhood. Qualitative and quantitative research indicates that among Latinx families of children with ASD, primary household language affects service access. Spanish-speaking families often encounter greater obstacles in scheduling appointments and receiving quality care compared to English-speaking families (Zuckerman, Sinche, Cobian, et al., 2014; Zuckerman, Lindly, Reyes, et al., 2017). These findings mirror broader challenges in mental health access for individuals with limited English proficiency in the U.S., where bilingual services are frequently recommended as a solution. However, language is often intertwined with immigrant status, poverty, and racial/ethnic minority status in the U.S. Despite the promotion of bilingual services, empirical research examining the impact of non-English service availability on timely ASD diagnosis in spanish or other languages is limited. This study leverages data from a research clinic offering ASD diagnostic evaluations in both English and Spanish to shed light on scheduling dynamics that create disparities in clinical settings, impacting appointment attendance. We aim to understand the mechanisms behind diagnostic delays for ASD – specifically, at which stages delays occur from screening to evaluation and diagnosis, and how these delays contribute to disparities in time to diagnosis. Understanding these systemic contributions is vital for developing strategies to promote equitable access to diagnostic and intervention services.

The process of identifying and diagnosing any childhood condition involves interactions between the healthcare system, the patient, and the caregiver. Each interaction point can influence the time to diagnosis in spanish or English. Once an evaluation is requested, the time-to-evaluation is influenced by: (a) clinic appointment availability, dependent on institutional resource allocation; (b) caregiver appointment choice, influenced by resources, flexibility, and motivation; (c) alignment between family and clinic schedules; and (d) completion of the scheduled appointment. Furthermore, cancellations or rescheduling by either the clinic or family can prolong the time to diagnosis. Variations in any of these factors can contribute to health disparities.

Analyzing both family-level (e.g., caregiver cancellations) and organizational-level variables (e.g., appointment availability) concurrently can clarify the reasons for disparities in time-to-diagnosis. This approach helps to avoid fundamental attribution errors, such as solely attributing delays to family-level factors (e.g., lack of resources) without considering organizational factors. By identifying the mechanisms of disparity, we can better target resources to mitigate them.

Administrative databases often contain data relevant to diagnostic timing processes, which can be valuable for research. For instance, shorter wait times have been linked to lower cancellation rates in children’s outpatient services (Dantas et al., 2018; Sherman et al., 2009), including ASD evaluation clinics (Kalb et al., 2012). The relationship between wait times and cancellation rates is likely complex (Sherman et al., 2009). Reduced wait times may offer families more schedule flexibility, decreasing cancellations. Conversely, longer waits may reduce motivation to pursue services. While wait time studies often use administrative data (Dantas et al., 2018; Kalb et al., 2012; Sherman et al., 2009), incorporating qualitative approaches can provide deeper insights by capturing family experiences with wait times. Historically, efforts to reduce wait times have focused on demand-side interventions, like minimizing family cancellations. More recently, attention has shifted to organizational-level factors influencing ASD diagnosis in spanish and English wait times. These efforts include expanding services to community settings and providing early intervention access during the diagnostic process (Gordon-Lipkin et al., 2016). Despite these interventions, racial and ethnic disparities in ASD diagnostic delays persist, necessitating further research into their underlying mechanisms.

This study provides a data-driven analysis of organizational factors contributing to disparities in ASD diagnosis within a university research clinic setting. Specifically, we explore child, family, and organizational factors that influenced wait times for diagnostic evaluations in young children screened as at-risk for ASD. The clinic was part of a larger study examining a Part C Early Intervention-based multi-stage screening and diagnostic evaluation protocol designed to address health disparities in ASD detection and diagnosis in spanish and English (Eisenhower et al., 2021). Previous analyses of this protocol showed no significant differences between Spanish- and English-speaking children in screening participation, positive screening rates, or ASD diagnosis rates (Eisenhower et al., 2021). However, disparities in the time taken during the detection process remained unexamined.

We hypothesized that analyzing organizational factors like appointment availability, selection, and cancellation would reveal crucial insights into the causes of diagnostic delays. We argue that overlooking organizational-level factors, such as clinic appointment availability, could lead to misinterpreting differences in completion times as solely resulting from family choices. We also incorporate findings from qualitative focus groups with English- and Spanish-speaking caregivers to contextualize our quantitative results. This study utilizes administrative data from clinic calendars and online scheduling systems to track screening completion dates, diagnostic evaluation request dates, open appointment slots at the time of request, family appointment choices, and appointment completion status (scheduled, rescheduled, or canceled). While focusing on early childhood ASD diagnosis in spanish and English, our methodology, adapted from adult medical literature (e.g., Dantas et al., 2018), is applicable to other childhood mental health conditions. A secondary goal is to demonstrate a methodology that can promote equitable access to child health and mental health services. Despite the research context of our clinic, its operational processes for appointment scheduling and completion mirror those in community-based settings.

Methods

We employed a sequential, mixed-methods, explanatory study design (Ivanoka, Creswell, & Stick, 2006). The quantitative phase aimed to identify the influence of child-, family-, and organizational-level characteristics on: (a) time to ASD evaluation, and (b) evaluation completion probability for families seeking English and Spanish language appointments. We were particularly interested in the role of appointment availability, an organizational factor, in explaining differences in completion time and rates between English and Spanish appointment groups. In the qualitative phase, focus groups were used to gain deeper understanding of caregiver perspectives on observed differences in time to and completion of ASD diagnostic evaluations across language groups. The University of Massachusetts Boston Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures, and informed consent was documented in writing.

Participants

Participants in the quantitative analyses were 353 families of young children (M = 24.66 months at diagnostic evaluation, SD = 5.04; 78.7% boys) referred for ASD diagnostic evaluations between November 1, 2014, and February 14, 2018, at a university research clinic partnering with three Part C Early Intervention (EI) agencies serving primarily low-resource families in a Northeastern urban area of the U.S. This sample is a subset of a larger study detailed elsewhere (Eisenhower et al., 2021). Eligibility criteria included: (a) enrollment in a participating EI agency, (b) no prior ASD diagnosis, (c) no medical condition limiting ASD diagnosis, (d) age between 14 and 33 months, and (e) a caregiver proficient in English or Spanish for screening questionnaires. Enrolled families were included if they were referred for diagnostic evaluation based on a two-stage screening process (Eisenhower et al., 2021).

Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The sample was diverse in race and ethnicity (83% non-White and/or Hispanic/Latinx), English proficiency (59% of caregivers rated English as “poor” or “fair”), and insurance status (76% public insurance). Caregiver language was categorized by the language of the booked appointment (English or Spanish). “English appointment” and “Spanish appointment” groups refer to families seeking evaluations in these languages. Bilingual families could choose either language. While analyses focus on English versus Spanish appointments, we acknowledge language as one way to categorize families accessing language-specific services. Language groups varied on other factors (Table 1) and potentially unmeasured factors (e.g., caregiver concern).

Table 1. Child, family, and organizational characteristics (% or means and standard deviations)

| Overall (N = 353) | English appointment families (n = 259) | Spanish appointment families (n = 94) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % of Sample | 100% | 73.4% | 26.6% |

| Child Characteristics | |||

| Age in Months | 24.66 (5.04) | 24.47 (5.22) | 25.19 (4.45) |

| Sex, % Male | 78.7%** | 75.7% | 87.0% |

| Mullen ELC Scores | 60.26 (11.31) | 60.69 (12.2) | 59.15 (8.53) |

| ADOS-2 Calibrated Severity Score | 7.55 (2.29)* | 7.79 (2.16) | 6.90 (2.50) |

| Vineland ABC standard score | 64.23 (10.1) | 63.62 (9.87) | 66.06 (10.53) |

| Family Characteristics | |||

| Income, % ≤ 185% FPL§ | 57.4%** | 47.9% | 80.0% |

| Caregiver employment status, % unemployed | 39.7% | 35.0% | 44.0% |

| Insurance, % on public insurance | 75.9%** | 68.8% | 94.2% |

| Education, % ≤ High school | 44.5%* | 38.6% | 59.8% |

| Race and ethnicity, % | |||

| Asian | 5.9%* | 8.2% | 0.0% |

| Black | 21.4%** | 28.6% | 2.4% |

| Latinx | 45.1%** | 26.4% | 94.0% |

| White (Non-Latinx) | 17.4%** | 24.1% | 0.0% |

| Multi-Ethnic/Racial | 3.3%* | 4.5% | 0.0% |

| Other or not reported | 6.9% | 8.2% | 3.6% |

| English Proficiency^ | 3.78 (1.44)** | 4.4 (1.01) | 2.19 (1.15) |

| Organizational characteristics | |||

| Appointment Availability, time to third next available appointment in days | 50.24 (42.52)** | 39.94 (36.44) | 74.59 (46.06) |

| Appointment Selection | 3.46 (2.41)** | 4.04 (2.49) | 2.09 (1.49) |

| Appointment Cancellation, % | 17.3% | 16.2% | 20.2% |

| Days from request for appointment to evaluation | 38.5 (19.21)** | 33.35 (15.29) | 50.66 (21.97) |

Note. Abbreviations: ABC, Adaptive Behavior Composite; ADOS-2, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-2; ELC, Early Learning Composite; FPL, federal poverty line.

^ 1-Poor, 2-Fair, 3-Good, 4-Very Good, 5-Excellent

* p < .05

** p < .01; p-values from χ2 tests or t-tests, representing statistical significance across the English and Spanish appointment families.

§ The income variable was missing 24% of data and was therefore not included in subsequent analyses.

For the qualitative study, we purposefully selected caregivers who primarily spoke English or Spanish. Participants were recruited from two of the three EI agencies involved in the larger study. The qualitative sample included 16 caregivers (12 English-speaking and four Spanish-speaking) in four focus groups. Three focus groups were conducted in English and one in Spanish. In the English focus groups, 83% were female, and 50% identified as non-Latinx White. In the Spanish focus group, all participants were female and identified as Latinx.

Procedures of the multi-stage screening and evaluation protocol

Screening procedures

Our research team trained Early Intervention providers (EI providers) at each EI agency to implement a multi-stage screening protocol as part of routine practice to facilitate earlier ASD diagnosis in spanish and English. All screening materials were available in both languages. Stage 1 involved caregiver completion of the Brief Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (BITSEA; Briggs-Gowan & Carter, 2006) and Parent Observation of Social Interaction (POSI; Smith et al., 2013). Children were referred to Stage 2 based on positive questionnaire results or caregiver/EI provider concerns about ASD. Stage 2 involved EI provider administration of the Screening Tool for Autism in Toddlers (STAT; Stone et al., 2000). Families were referred for diagnostic evaluation if children scored positive on the STAT or if EI providers reported ASD concerns.

Booking diagnostic evaluations

When a child screened positive at Stage 2, EI providers booked diagnostic evaluation appointments using online software (www.YouCanBook.Me). This software notified study staff, updated clinic calendars, blocked time slots, and recorded booking and appointment dates/times. Separate online calendars were used for booking English and Spanish appointments.

Diagnostic evaluations

Diagnostic evaluations were conducted with caregivers and EI providers present by trained research assistants or doctoral students in Clinical Psychology, supervised by licensed psychologists specializing in early childhood ASD diagnosis in spanish and English. Evaluations included the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2; Lord et al., 2000), Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995), Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Third Edition (Sparrow et al., 2016), and a developmental/medical history interview. Licensed psychologists assigned final DSM-5 ASD diagnoses after observing the evaluation and reviewing all information. Diagnostic appointments were available with English-speaking or bilingual (Spanish) teams, with a weekly ratio of approximately one Spanish to three English slots. Therefore, appointment availability varied by language. Screening and diagnostic evaluations, and transportation, were provided free of charge. While common access barriers were removed, scheduling logistics, limited appointment availability, and wait times mirrored community clinics. This strengthens the study by allowing a clearer focus on organizational processes.

Measures

Primary outcomes: Time until and completion of diagnostic evaluations

Time to evaluation was calculated as days between positive Stage 2 screening (referral date) and completed diagnostic evaluation date. The date of scheduled diagnostic evaluation appointment (request date) was also recorded. A binary variable, “evaluation completion,” indicated whether the evaluation was completed, even if rescheduled.

Independent Variables: Child- and Family-Level Factors

Child factors included age, developmental functioning, ASD severity, and adaptive functioning. Family factors included language of evaluation (proxy for caregiver language), race/ethnicity, insurance status, caregiver employment, and education level.

Potential mechanisms: Availability, selection, and cancellation of diagnostic evaluation appointments

Appointment availability was defined as appointment options open to caregivers when requesting an evaluation. We hypothesized that appointment availability, selection, and cancellation, organizational-level factors, would mediate the relationship between demographic factors and evaluation completion likelihood and time. For appointment availability, we calculated days to the 1st through 9th available appointments (English or Spanish calendars) on the day of each family’s request. Following guidelines, days to the third next available appointment was used as a proxy for appointment availability (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, n.d.). This metric is solely influenced by organizational factors. We assessed days to available appointments but not time-of-day or day-of-week flexibility.

Appointment selection was operationalized as the ordinal rank of the chosen appointment (1st, 2nd, etc., available). A smaller number indicates choosing an earlier appointment. This metric reflects family factors and/or interactions between organizational and family factors.

Appointment cancellation/reschedule was a binary variable indicating any cancellation or rescheduling. Clinic calendars were used to determine appointment status. Cancellation can reflect family or organizational factors. Rescheduling sometimes occurred to earlier dates if slots opened up.

Clinic capacity to conduct evaluations

Weekly appointment numbers varied due to demand fluctuations, staffing changes, and availability of bilingual staff. Appointment offerings ranged from 1-2 Spanish and 2-4 English appointments weekly, a higher Spanish-to-English ratio than initially planned to meet demand. English and Spanish appointments were booked on separate calendars, resulting in different availability for each language group.

Qualitative measures

We used a survey and focus group guide to identify caregiver perceptions of factors facilitating completion rates (Appendix A). The English guide was translated into Spanish and back-translated to ensure comparability. Focus groups (45-60 minutes) covered: (a) experiences with ASD screening, (b) benefits/challenges of the multi-stage protocol and evaluation, and (c) perspectives on universal ASD screening in primary care versus EI settings.

Analytic Approach

Quantitative analyses

Quantitative analyses were conducted in Stata version 15. Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic and baseline variables for the total sample and language groups. Box plots illustrated appointment availability differences across language groups. Cox regression models estimated time-to-evaluation and completion probability. Proportional hazards assumptions were checked with interaction tests. Significant associations were further analyzed using path analyses with structural equation models (SEM) to test mediation (more powerful than Baron and Kenny’s method; Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). SEM model fit is not reported as models were saturated.

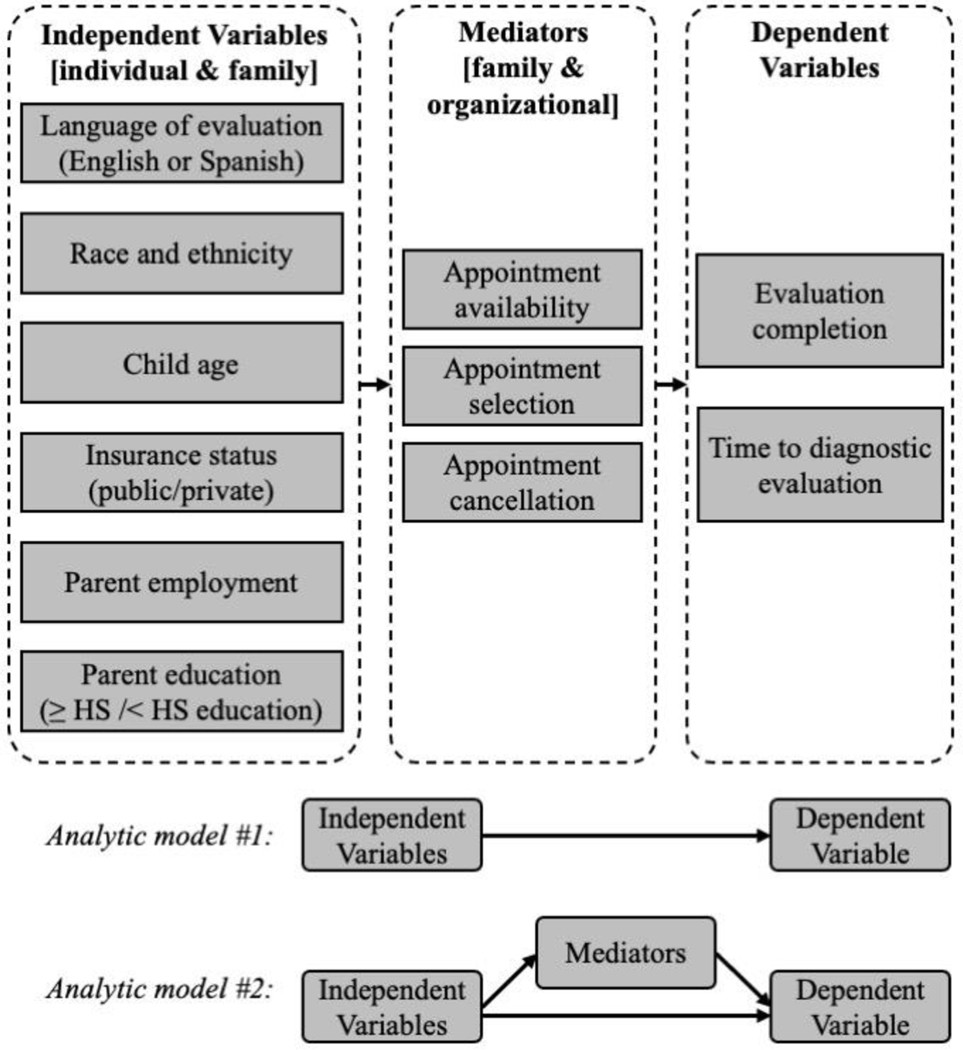

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model. The primary focus was the effect of caregiver language (English or Spanish appointment) on time-to-evaluation and completion probability. Socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity variables were included based on prior research linking them to appointment cancellations (Daniels & Mandell, 2014). Mediating variables included: (a) appointment availability (days to third next available appointment), (b) appointment selection (rank of chosen appointment), and (c) appointment cancellations. Sensitivity analyses examined child symptoms and functioning associations with wait times.

Figure 1. Conceptual model and analytic plan

Qualitative analysis

Three English and one Spanish focus group transcripts were analyzed. Spanish transcripts were professionally translated and then back-translated by research team members to ensure accuracy. Team members (TIM, LR) inductively coded transcripts, highlighting key terms, experiences with scheduling/attending appointments, and passages relevant to appointment availability and attendance (Corbin & Strauss, 1990). Team meetings validated data, reviewed codes, and identified patterns across focus groups (Charmaz, 1990; Willms et al., 1990). Themes were identified through persistent engagement with text, team discussions, and seeking disconfirming evidence. Findings highlight common themes facilitating evaluation completion and unique experiences of the Spanish-speaking group to understand observed differences in time to diagnosis in spanish and completion probability.

Results

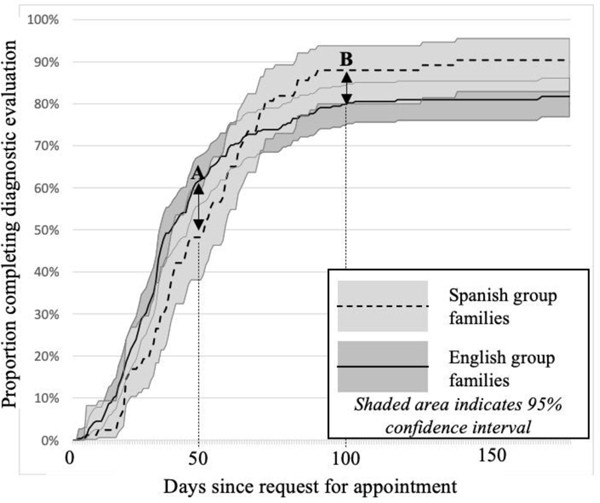

Descriptive statistics are in Table 1. Cox regression analysis showed that among tested variables, only language of evaluation was associated with time-to-evaluation (p = .01). Spanish appointments had approximately 2.5 weeks longer wait times. However, language of evaluation interacted with time (p = .004), violating proportional hazards assumption, preventing joint analysis of time to evaluation and completion probability in a single Cox model. Survival curves (Figure 2) showed that Spanish appointment completion rates lagged English rates until ~65 days post-request, after which Spanish rates exceeded English rates. Therefore, within 65 days, English appointments had higher completion likelihood, but beyond 65 days, Spanish appointments had higher completion likelihood among remaining families. Due to violation of proportional hazards assumption, separate SEMs were conducted for: (a) evaluation completion probability, (b) time from Stage 2 screening to appointment request, and (c) time from request to evaluation (among those who completed). SEM approach allowed for testing parameter equality across language groups.

Figure 2. Completion of diagnostic evaluation by English versus Spanish appointment group families

Note. Point A: 50 days after request for appointment, 48.2% of Spanish group families and 61.2% of English group families have completed evaluations. Point B: 100 days after request for appointment, 88.0% of Spanish group families and 79.1% of English group families have completed evaluations.

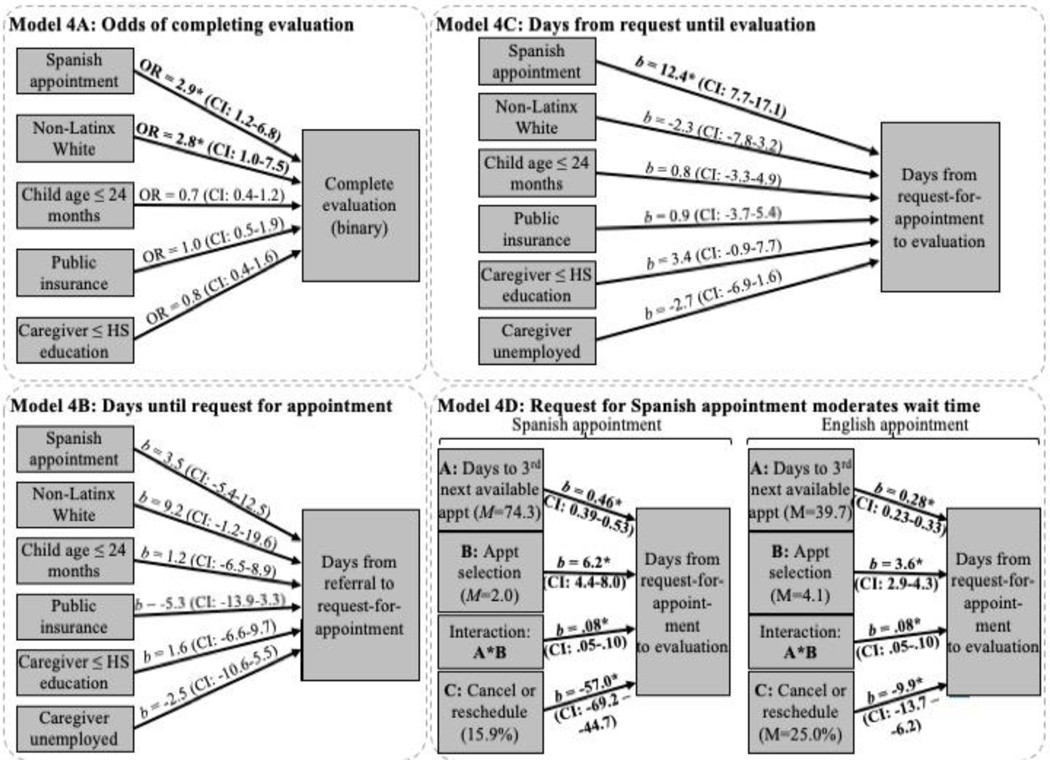

Predicting evaluation completion

A SEM examined odds of evaluation completion. Caregiver unemployment perfectly predicted completion and was removed. Generalized SEM (log link for binary outcome) revealed no parameter equality differences across Spanish language appointment groups (except for White families). Figure 4A shows positive associations between booking a Spanish appointment (OR = 2.9, p = .02) and evaluation completion, and identifying as White (OR = 2.9, p = .04) in the English group. No other variables were significant (Figure 4A). Spanish appointment families (91.6% Latinx) had higher completion rates (88.0% within 100 days) than English appointment families (79.1% within 100 days, 29.9% Latinx). White families (English evaluations) also had higher completion rates than Latinx/non-White families. Mediators were only measured among completers, and no path analysis was conducted for this outcome.

Figure 4. Results of SEM analyses

Note: Caregiver unemployment perfectly predicted the outcome for Model 4a and therefore was dropped from the model.

Abbreviations: Appt, Appointment; HS, High School; OR, Odds Ratio

Predicting days from referral to request for appointment

SEM for time from Stage 2 screening to appointment request (Figure 4B) showed no parameter equality differences across language groups and no significant associations with any independent variable. Spanish appointment families descriptively took slightly less time to request appointments, while White families (English group) took somewhat longer. No path analysis was conducted due to lack of significance.

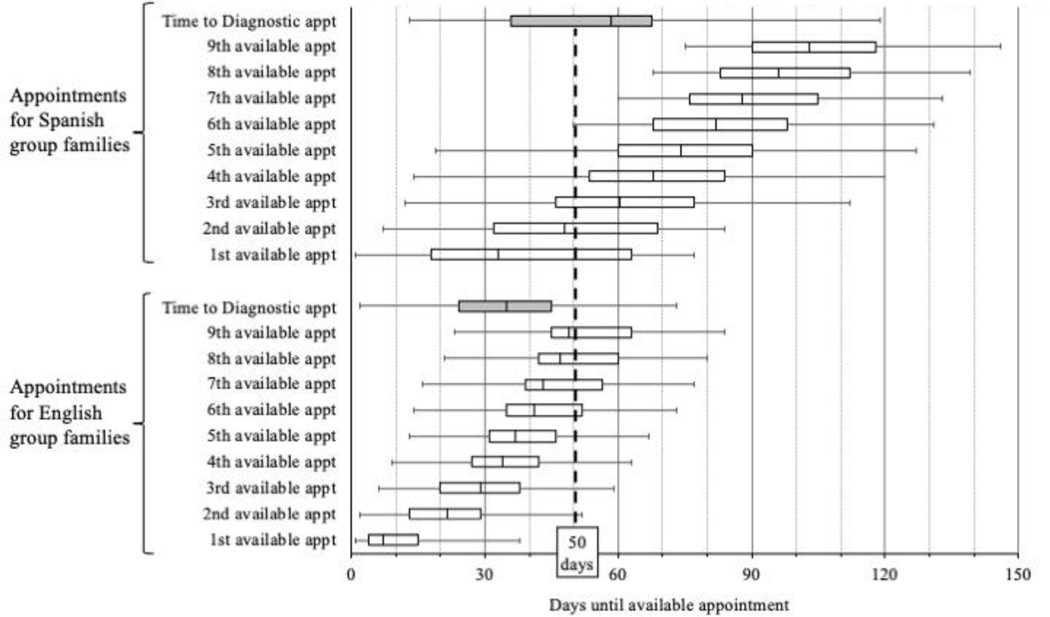

Predicting time from request for appointment to evaluation

Figure 3 shows box plots of appointment availability differences. Spanish evaluations had fewer available appointments within 50 days compared to English evaluations.

Figure 3. Differences in appointment availability for families seeking English (n = 259) versus Spanish (n = 94) appointments

Note. Box-and-whisker plots represent the minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum. Plots shaded gray represent days until scheduled English and Spanish language appointments occurred. Plots shaded in white represent days until available appointment options for each group.

SEM for time from request to evaluation (Figure 4C) showed no parameter equality differences. Booking a Spanish appointment was associated with longer wait times (b = 12.4, p < .001). Path model with mediators (appointment availability, selection, cancellation/rescheduling, and interaction between availability and selection) predicted 63.2% of variance. Separate SEMs for English and Spanish appointment families (Figure 4D) revealed that means and coefficients differed by language. Appointment availability was higher for Spanish families and had a larger effect on wait time (b = 0.48 vs 0.28; p < .05). Appointment selection and cancellation also had different effects across language groups (see Figure 4 and Supplemental Table 1).

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses found no significant associations between child factors (developmental functioning, ASD severity, adaptive functioning) and time to evaluation, appointment selection, or cancellations. Language of evaluation remained significant in regression models including child factors.

Qualitative analyses

Qualitative analyses revealed that both English- and Spanish-speaking families valued a clear pathway from screening to ASD diagnosis in spanish and English facilitated by EI providers. A Spanish-speaking participant highlighted the circuitous path before EI intervention:

“Look, [Child’s name] did have a screening, now which she [the pediatrician] said is for autism … but I was only focused on [starting] the early intervention. The early intervention did not evaluate him [for autism], it was only by medical referral. Almost at the year marker that I was in early intervention, the EI provider observed different things in [Child’s name] – so she told me “Look, I am not a specialist. You need this to be done by a special team.” And so the EI coordinator referred me to [University site].” – Spanish Focus Group, translated (original text in Supplemental Table 2).

Facilitating factors included: (a) bidirectional information exchange during screening, and (b) emotional support from EI providers. Spanish-speaking participants also valued culturally responsive evaluations and free transportation.

Both language groups valued bidirectional expertise exchange during screening, enabling caregivers to learn about child needs and intervention options. English-speaking caregivers expressed the need for more information from EI providers, particularly on developmental milestones.

EI providers provided emotional support, guiding families despite potential lack of family support. Spanish-speaking caregivers valued Spanish evaluations responsive to cultural and linguistic needs, citing concerns about culturally insensitive evaluations elsewhere. They noted cultural beliefs that might hinder ASD diagnosis in spanish within their communities.

Participant 2: There are many times in our culture, or depending on the nationality of the people, [that people] have a tendency to say…

Participant 3: Autism.

Participant 2: There. These illnesses [autism] do not exist.

Participant 4: [Or say] your child acts like that because it is normal [to behave that way]. – Spanish Focus Group, translated.

Spanish-speaking caregivers valued EI provider strategies to address family reluctance towards evaluation. Long waitlists for Spanish evaluations in the community were also reported. The research clinic addressed barriers to linguistically and culturally responsive diagnosis in spanish. Free transportation was uniquely valued by Spanish-speaking caregivers, addressing challenges of transporting toddlers without a car.

Participant 3: And we don’t have a car and … (on the bus) is how I must go. And sometimes they tell me, the ladies [referring to bus drivers], ‘I admire you.’ Because sometimes they wait for me at the door, and sometimes I am a few minutes late and they are going to arrive at the house, and I go running with the stroller with the child like a crazy person to all the appointments, or whatever it is.

Participant 2: Because it is terrible …

Participant 3: To go in the cold running with the child.

Participant 2: And it is not for nothing that for the diagnostic [evaluation] they also give it [transportation] to you. – Spanish Focus Group, translated.

Discussion

Disparities in ASD screening and diagnosis in spanish and English are well-documented, but modifiable mechanisms are rarely examined. This study investigated organizational factors and found that Spanish language status was associated with both higher evaluation completion and longer wait times. Despite longer waits due to limited Spanish appointments, Spanish-speaking families were more likely to complete evaluations. SEM analyses indicated that appointment availability, not cancellations or appointment selection, explained longer wait times for Spanish appointments. Spanish-speaking families chose earlier ranked appointments but still experienced longer waits due to limited availability. Organizational factors, specifically appointment availability, were the primary driver of disparities.

Qualitative findings suggest the multi-stage screening protocol guided caregivers toward diagnosis in spanish or English through bidirectional expertise exchange and emotional support. The limited availability of Spanish evaluations in the community may have increased the perceived value of research-based evaluations among Spanish-speaking families. Efforts to address cultural and linguistic barriers may also have contributed to higher participation (DuBay et al., 2018; Vigil & Hwa-Froelich, 2004; Zuckerman, Sinche, Cobian, et al., 2014). Higher completion rates in Spanish-speaking families may indicate resilience and strong follow-through once motivated. Organizations should prioritize pre-diagnostic engagement with Spanish-speaking families, emphasizing evaluation importance and process. Conversely, English-speaking non-completers may have sought evaluations elsewhere, an option less available for Spanish-speaking families. We recommend recruiting and training bilingual/bicultural staff. When interpreters are necessary, their expertise in ASD terminology should be considered, and organizations should establish protocols for linguistic services, including workflow adjustments and longer appointment slots. Language accessibility is an organizational responsibility, not just individual staff.

Transportation assistance also appeared more critical for Spanish-speaking families, addressing a significant social determinant of health (Yang et al., 2006). Free transportation linked to the screening protocol may have met their needs. Qualitative findings highlight how intersecting factors like language barriers, immigrant experiences, and financial constraints shape experiences with ASD diagnosis in spanish. Leveraging IDEA programs and services like transportation can reduce access disparities.

Methodologically, this study demonstrates the value of analyzing child-, family-, and organizational-level factors to understand disparity mechanisms. Organizational factors, not family or child factors, explained diagnostic delays in our study. Regular monitoring of equity and access is crucial for organizations providing diagnostic and intervention services. Even in a study designed to address barriers, systemic delays for Spanish appointments persisted due to lack of routine monitoring and timely resource reallocation.

Analyzing appointment availability offers concrete, actionable insights into diagnostic delays. Our results support the importance of assessing appointment availability to understand disparities. Modeling appointment availability reveals supply-side issues contributing to documented disparities in ASD diagnosis in spanish and English time. Analyzing organizational factors is generalizable to other childhood conditions and can be broadly used by clinics. Administrative data on appointment availability should be routinely monitored. Organizations could use dashboards to track appointment availability by language, alerting staff to discrepancies. Qualitative interviews can provide direct family insights. Mixed-methods approaches, like this study, combine administrative data and lived experiences for a comprehensive understanding.

Analyzing multi-level factors reduces unfounded assumptions that delays are solely family-driven. Despite efforts to promote Spanish-speaking family participation, limited access to Spanish-speaking EI providers and a 1:3 Spanish-to-English appointment ratio still resulted in longer wait times for Spanish appointments. A ratio matching population demographics is insufficient for equitable time to evaluation, though it may achieve overall evaluation completion equity. Resource limitations and misconceptions about equitable access led to disparities. Bilingual families might prefer Spanish appointments if wait times were equal. Systems should anticipate higher demand for linguistically responsive services from non-English speaking families due to ongoing barriers elsewhere. Systems should build in greater availability for bilingual appointments than population needs suggest. Qualitative data complements quantitative indicators, providing richer insights.

Limitations include modest sample sizes and focus on one referral chain link. Results are best interpreted as a case study supporting the utility of organizational-level factor analysis and methods using readily available data. Measurement error and use of proxy measures like days to third next appointment exist. Cancellation data was limited. Findings from a research-based clinic may not fully generalize to community clinics due to potentially higher service quality.

In conclusion, mixed-methods approaches are valuable for analyzing and monitoring equity in access to services. Organizational-level factor analysis reveals mechanisms explaining wait time disparities beyond individual and family factors. These methods should be used to actively monitor equity in childhood diagnostic and intervention services. Qualitative data provides unique, complementary insights. Addressing organizational factors is essential for culturally responsive care, alongside focusing on child and family levels.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 2

NIHMS1766977-supplement-Supplemental_Table_2.docx (21.2KB, docx)

Supplemental Appendix A

NIHMS1766977-supplement-Supplemental_Appendix_A.docx (24.1KB, docx)

Supplemental Table 1

NIHMS1766977-supplement-Supplemental_Table_1.docx (87.2KB, docx)

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under Grant R01MH104400; Health Resources Services Administration under Grant R40MC26195; and Autism Speaks under grant AS #7415.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Sheldrick and Dr. Carter are co-creators of the POSI, which is one of the two first-stage screeners used in this study. They conduct research related to this instrument but receive no royalties. Dr. Carter is also co-creator of the BITSEA, which is one of the two first-stage screeners used in this study. Dr. Carter receives royalties on the sale of the BITSEA, which is distributed by MAPI Research Trust.

References

[References section from the original article, maintain all references]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 2

NIHMS1766977-supplement-Supplemental_Table_2.docx (21.2KB, docx)

Supplemental Appendix A

NIHMS1766977-supplement-Supplemental_Appendix_A.docx (24.1KB, docx)

Supplemental Table 1

NIHMS1766977-supplement-Supplemental_Table_1.docx (87.2KB, docx)