Osteoarthritis (OA), particularly in the knee, stands as the most prevalent joint disorder affecting adults globally. As a leading cause of pain and disability, especially with advancing age, comprehending its complexities is paramount. While the quest for a definitive cure continues, the most potent approach to managing knee osteoarthritis lies in prevention. This article delves into the multifaceted nature of knee osteoarthritis, emphasizing the critical relationship between diagnosis and etiology – understanding the underlying causes to achieve accurate identification and effective intervention. Just as etiology is the study of causation, diagnosis in knee osteoarthritis aims to pinpoint the specific nature and extent of the condition, guiding targeted and effective treatment strategies.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors: Setting the Stage for Osteoarthritis

Knee osteoarthritis is a widespread concern, with studies indicating that a significant portion of the adult population exhibits radiological signs of the disease. While not all radiological findings correlate with clinical symptoms, the prevalence of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis remains substantial, affecting approximately 6% of adults. The likelihood of developing this condition escalates with age, with prevalence rates soaring to as high as 40% in individuals aged 70 to 74. Interestingly, epidemiological data reveals gender-specific patterns in knee involvement. Men aged 60 to 64 are more prone to right knee osteoarthritis, while women exhibit a more balanced distribution between both knees.

Figure 1: Radiographic evidence of advanced knee osteoarthritis, illustrating severe joint space narrowing and bone changes.

Understanding the etiology of knee osteoarthritis requires acknowledging both endogenous (intrinsic) and exogenous (extrinsic) risk factors. Endogenous factors encompass age, sex, heredity, and ethnicity. Genetic predisposition plays a role, although osteoarthritis is typically a complex polygenic condition influenced by multiple genes rather than a single gene defect. Exogenous factors, on the other hand, include macrotrauma, repetitive microtrauma, overweight or obesity, prior joint surgery, and lifestyle choices. Occupational hazards, such as frequent kneeling or squatting, as seen in underground coal miners and construction workers, significantly elevate the risk of knee osteoarthritis. Furthermore, a clear dose-response relationship exists between excess weight (BMI >30) and the risk of knee osteoarthritis, highlighting the modifiable nature of some etiological factors.

| Endogenous Risk Factors | Exogenous Risk Factors |

|---|---|

| Age | Macrotrauma (e.g., knee injury) |

| Sex | Repetitive Microtrauma (e.g., occupational stress) |

| Heredity | Overweight and Obesity |

| Ethnic Origin (European descent more susceptible) | Resective Joint Surgery |

| Post-menopausal Changes | Lifestyle Factors (alcohol, tobacco use) |

Table 1: Key factors contributing to the development of knee osteoarthritis, categorizing them into intrinsic and extrinsic influences.

Etiology and Pathophysiology: Deciphering the Origins of Joint Degeneration

Knee osteoarthritis is broadly classified into primary (idiopathic) and secondary forms. Primary osteoarthritis arises without a clear underlying cause, often attributed to the cumulative effect of aging and general wear and tear. Secondary osteoarthritis, conversely, develops as a consequence of identifiable factors such as trauma, congenital abnormalities, malalignment (varus/valgus deformities), post-surgical conditions, metabolic disorders, endocrine imbalances, or aseptic osteonecrosis.

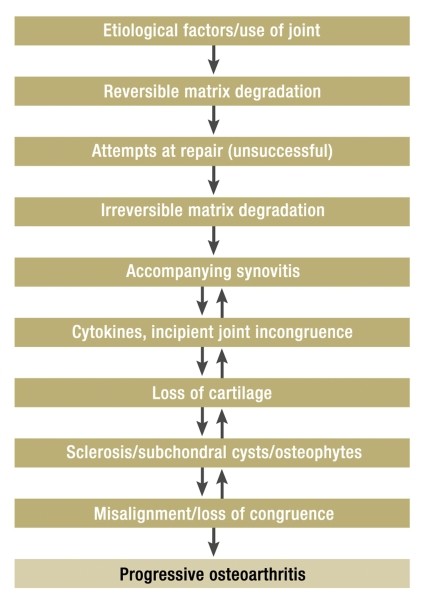

At the core of osteoarthritis pathology lies the hyaline cartilage, the specialized tissue that cushions and facilitates smooth joint movement. This cartilage, primarily composed of extracellular matrix, is the primary target in osteoarthritis. The concept of the “organ of articulation” emphasizes the interconnected function of all joint structures – from bone and cartilage to ligaments, menisci, and muscles. Disruptions in the dynamic equilibrium between cartilage matrix formation and breakdown initiate the osteoarthritic process.

Figure 2: A simplified representation of osteoarthritis pathogenesis, illustrating the interplay of mechanical and enzymatic factors in cartilage breakdown.

This equilibrium is maintained by a delicate balance of anabolic (building) and catabolic (breaking down) influences. Anabolic factors like insulin-like growth factors promote matrix synthesis, while catabolic factors such as interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and proteinases contribute to matrix degradation. When catabolic influences overwhelm the compensatory mechanisms, cartilage degradation ensues, marking the initial step in osteoarthritis progression. While the precise mechanisms driving cartilage degeneration are still under investigation, mechanical stress and enzymatic degradation are considered key contributors to chondrocyte dysfunction and matrix damage.

Diagnostic Evaluation: Linking Symptoms to Etiology

Effective management of knee osteoarthritis hinges on accurate diagnosis. The diagnostic process aims to confirm the presence of osteoarthritis and exclude other conditions, ensuring targeted treatment. A comprehensive diagnostic evaluation integrates medical history, physical examination, imaging studies, and, in specific cases, laboratory investigations.

History and Physical Examination: Unveiling Clues through Patient Presentation

Patients with knee osteoarthritis typically present with activity-related pain, often described as a dull ache that worsens with initial movement or weight-bearing. As the disease advances, pain may become persistent, even occurring at rest or nocturnally, significantly impacting joint function. Key historical features suggestive of osteoarthritis include pain at the start of movement, during movement, and at rest, alongside stiffness, limited range of motion, and functional impairment in daily activities. Crepitus (joint noise) and sensitivity to cold or damp conditions are also commonly reported symptoms.

Physical examination plays a crucial role in assessing the stage and severity of osteoarthritis. Pain elicited by movement and relieved by rest is a hallmark finding. Persistent pain at rest may indicate advanced disease. The physical exam should encompass inspection, palpation, range of motion assessment, and specific functional tests. Ligament stability testing (varus/valgus stress, drawer tests for cruciate ligaments) and meniscal tests are essential to rule out other knee pathologies. The patellofemoral joint should also be evaluated for signs of irritation and patellar mobility, including tests like the Zohlen test (pain upon patellar compression during quadriceps contraction). Gait analysis may reveal limping due to pain or leg length discrepancy.

Imaging Studies: Visualizing Osteoarthritis

Radiographic imaging, primarily plain radiography (X-rays), is fundamental in both initial diagnosis and monitoring osteoarthritis progression. Standardized anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views are essential. Functional views may be added to address specific diagnostic questions. Radiological features of knee osteoarthritis are systematically staged using the Kellgren-Lawrence grading system, which ranges from stage 0 (no abnormalities) to stage 4 (severe joint destruction).

| Kellgren-Lawrence Stage | Radiographic Features |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Normal X-ray |

| Stage 1 | Doubtful joint space narrowing, possible osteophytes |

| Stage 2 | Definite joint space narrowing, osteophytes |

| Stage 3 | Moderate joint space narrowing, multiple osteophytes, some sclerosis and cyst formation |

| Stage 4 | Severe joint space narrowing, large osteophytes, marked sclerosis and cyst formation, deformity |

Box 3: Kellgren-Lawrence Grading System for Knee Osteoarthritis, outlining radiographic severity stages.

While supplementary imaging modalities like MRI, bone scanning, and ultrasonography may be used in specific situations, they generally do not provide significant additional diagnostic value for routine osteoarthritis assessment. MRI can visualize cartilage and soft tissues but is not typically necessary for initial diagnosis. Ultrasonography is useful for soft tissue and effusion evaluation but is highly operator-dependent.

Staging and Clinical Severity: Quantifying Osteoarthritis Impact

Staging systems, like the Kellgren-Lawrence radiographic staging, and clinical indices, such as the WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index), are used to assess the severity of osteoarthritis. The WOMAC index quantifies pain, stiffness, and functional limitations, providing a reproducible measure of disease impact. Joint-specific scoring systems also exist, incorporating both subjective and objective criteria to evaluate disease severity.

Treatment Strategies: Addressing Etiology and Symptoms

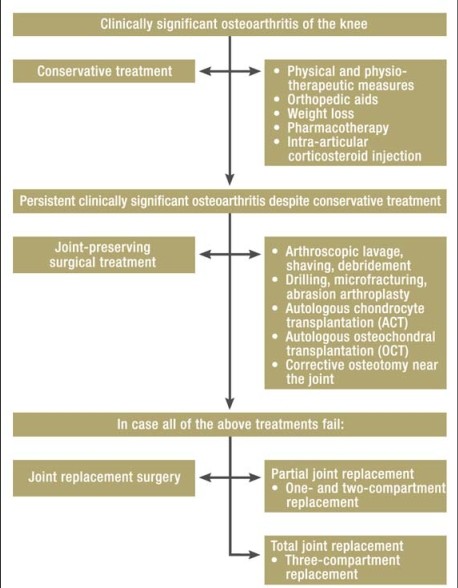

As osteoarthritis remains a non-curable condition, the primary goals of treatment are symptom alleviation and slowing disease progression. The therapeutic spectrum spans conservative measures to surgical interventions. Prevention remains the cornerstone of management. Treatment strategies are tailored to the individual patient, considering symptom severity, disease stage, and overall health status.

Conservative Treatment: A Stepwise Approach

Conservative management forms the initial and often ongoing approach to knee osteoarthritis. It follows a stepwise algorithm, individualized to each patient’s needs. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines and similar national guidelines advocate for a combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological approaches.

| EULAR Stepwise Recommendations for Conservative Treatment |

|---|

| 1. Combine non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatments. |

| 2. Tailor treatment to risk factors, pain severity, effusion, and osteoarthritis damage. |

| 3. Non-pharmacological: weight loss, orthotics, physiotherapy. |

| 4. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) as first-line analgesic for long-term use (if effective). |

| 5. Topical NSAIDs for pain relief. |

| 6. Opioid analgesics if paracetamol/NSAIDs are inadequate. |

| 7. SYSADOAs (Symptomatic Slow-Acting Drugs for Osteoarthritis) for symptom relief. |

| 8. Intra-articular corticosteroids for effusion and severe pain. |

Box 4: EULAR Guidelines for Conservative Knee Osteoarthritis Management, emphasizing a multimodal approach.

Non-pharmacological measures include patient education, lifestyle modifications, and weight loss if indicated. Reducing joint stress through activity modification and appropriate footwear is crucial. Physiotherapy encompasses exercise therapy and physical modalities like ultrasound, electrotherapy, heat/cold application, manual therapy, and acupuncture. Orthopedic aids, such as cushioned insoles and shoe wedges, can correct malalignment and reduce joint load. Knee orthoses can also provide pain relief and improve function.

Pharmacological treatment includes analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, and SYSADOAs. Paracetamol is often the first-line analgesic. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) offer pain relief and anti-inflammatory effects, but their use requires consideration of potential side effects. Intra-articular corticosteroid injections can provide short-term relief from pain and effusion. SYSADOAs, like glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, are thought to have a slower onset of action but may offer long-term symptom benefit for some patients.

| Non-Pharmacological Treatment Modalities | Evidence Level | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Physiotherapy | Ia | Pain relief, functional improvement |

| Orthotics | Ib | Positive effect on pain and function |

| Ice Treatment (Massage/Compresses) | Ib | Massage improves flexion/extension; Compresses no pain reduction |

| Electrical Stimulation (TENS) | Ia | Pain relief, improved mobility |

| Ultrasound | Ib | No significant effect |

Table 2: Evidence-based non-pharmacological treatments for knee osteoarthritis, summarizing effectiveness and evidence levels.

Surgical Treatment: When Conservative Measures Fall Short

Surgery is considered when conservative treatments fail to provide adequate symptom relief and functional improvement, and when radiological findings correlate with clinical severity. Joint-preserving surgical options range from arthroscopic procedures to osteotomies.

Arthroscopic procedures include lavage (joint irrigation), debridement (removal of damaged cartilage and bone), and chondroplasty (cartilage smoothing). While arthroscopy is minimally invasive, evidence for its long-term efficacy in osteoarthritis is limited. Bone-stimulating techniques like microfracturing aim to stimulate cartilage repair by accessing subchondral stem cells. Cartilage restoration techniques, such as autologous chondrocyte transplantation (ACT) and autologous osteochondral transplantation (OCT), are used to repair cartilage defects in younger, more active patients with localized cartilage damage.

Corrective osteotomy involves surgically realigning the bones around the knee to shift weight-bearing away from the damaged joint compartment. Osteotomy can be beneficial in younger patients with malalignment and early-stage osteoarthritis.

In advanced osteoarthritis, joint replacement (arthroplasty) becomes the definitive surgical option. Total knee arthroplasty involves replacing the entire knee joint with artificial components, providing significant pain relief and functional restoration.

| Joint-Preserving Surgical Options | Description |

|---|---|

| Arthroscopic Lavage & Debridement | Irrigation and removal of debris/damaged tissue |

| Microfracturing | Stimulating cartilage repair through subchondral bone access |

| Autologous Chondrocyte Transplantation (ACT) | Transplanting cultured cartilage cells |

| Autologous Osteochondral Transplantation (OCT) | Transplanting bone and cartilage plugs |

| Corrective Osteotomy | Realigning bones to redistribute joint load |

Box 5: Joint-preserving surgical options for knee osteoarthritis, outlining different procedural approaches.

Conclusion: Diagnosis and Etiology – Cornerstones of Osteoarthritis Management

Knee osteoarthritis is a complex and prevalent condition. Effective management necessitates a comprehensive understanding of its etiology and a precise diagnostic approach. Just as Diagnosis Is To Etiology As identification is to cause, accurately diagnosing knee osteoarthritis requires considering its diverse underlying causes and risk factors. Prevention, through lifestyle modifications and risk factor management, remains the most impactful strategy. For established osteoarthritis, a stepwise, individualized treatment plan, encompassing both conservative and, when necessary, surgical options, aims to alleviate symptoms, improve function, and enhance quality of life. Continued research into the pathogenesis and treatment of osteoarthritis is crucial to developing more effective therapies and ultimately, a cure for this debilitating condition.

Figure 3: A treatment algorithm for knee osteoarthritis, illustrating the stepwise progression from conservative to surgical interventions based on disease severity.

References

References are the same as in the original article.