Background

Anxiety disorders represent a significant global mental health challenge, affecting a considerable portion of the population annually [1]. These conditions are not merely transient worries; they are associated with substantial impairments in daily functioning, impacting occupational and social aspects of life, often leading to unemployment, social isolation, and strained relationships [2]. In fact, anxiety disorders are a leading cause of disability worldwide, contributing more to years lived with disability than any other mental health condition and surpassing many physical ailments in their impact [3].

Primary care settings are the frontline in managing anxiety disorders, as they are frequently the first point of contact for individuals seeking help. Despite their prevalence, less than half of those experiencing an anxiety disorder actively seek professional help [4–6]. Treating anxiety within primary care offers significant advantages, including improved accessibility and reduced financial burden for patients. Integrating mental health services into primary care is recognized as a crucial step towards achieving universal health coverage [7]. However, a concerning reality is that only a small fraction of individuals seeking help in primary care receive adequate treatment for their anxiety [8, 9]. Untreated or inadequately managed anxiety disorders often follow a chronic course, leading to persistent distress for the individual and substantial economic costs due to repeated healthcare utilization and decreased productivity [3, 10]. Furthermore, delayed or insufficient treatment elevates the risk of developing co-occurring conditions like depression and substance use disorders, which further complicate the clinical picture and increase overall impairment [10].

A range of healthcare professionals in primary care may be involved in the diagnosis and treatment of anxiety disorders, including social workers, nurses, and psychologists. However, general practitioners (GPs) remain the primary providers of care for these conditions [6, 11]. Best practice in managing anxiety disorders involves a stepped-care approach, tailored to the severity of symptoms, functional impairment, and considering co-occurring issues, patient preferences, and prior treatment experiences [12, 13]. These steps vary depending on the specific anxiety disorder, starting with low-intensity psychological interventions such as guided or unguided self-help and psychoeducation for milder cases. For more moderate to severe anxiety or when initial low-intensity interventions are not effective, higher-intensity treatments like individual cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or medications are recommended [14, 15]. Referral to specialist mental health services outside of primary care should be considered for complex and severe cases [14, 15]. Clinical guidelines generally recommend psychological interventions as the first-line approach, favoring them over pharmacological treatment [12]. Despite this recommendation, pharmacological interventions are often the most common treatment modality in primary care, regardless of anxiety severity [8, 11], even though research indicates that patients often prefer psychological therapies [16, 17].

While GPs may not routinely deliver high-intensity psychological treatments due to time constraints and limited specialized training [18, 19], they are well-positioned to offer low-intensity interventions such as psychoeducation and self-help programs. Computerized or internet-delivered CBT, in particular, has demonstrated effectiveness in treating anxiety and can be comparable in efficacy to face-to-face CBT [20, 21]. These programs typically involve modules accessible via desktop, internet, or phone applications, making them suitable for primary care delivery, either with clinician support (guided) or independently (unguided) [20].

For cases requiring higher intensity therapies, face-to-face CBT can be delivered in primary care by non-specialist providers such as nurses. This approach has been a focus of research aimed at improving access to these evidence-based treatments [22]. However, funding for non-specialists to provide psychosocial interventions remains a challenge in many healthcare systems, potentially contributing to the continued reliance on GPs as primary care providers for anxiety disorders. Although evidence is growing for psychological interventions delivered by non-specialists, much of the existing outcome research involves treatment provided by mental health specialists. For example, a previous systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological treatment in primary care indicated a moderate effect size for reducing anxiety symptoms [23]. However, it’s important to note that many studies included in that review involved treatment delivered by clinical psychologists, who are not typically integrated into primary care settings.

Medications like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are also recommended treatments for anxiety disorders [12, 13], potentially offering a more cost-effective and accessible option compared to psychological therapies. However, their effectiveness in primary care populations, particularly without concurrent psychological support, remains less clear. Benzodiazepines, while not currently recommended as a primary treatment, are still frequently prescribed for anxiety [24, 25]. Notably, there has been a gap in the literature regarding comprehensive reviews of pharmacological anxiety interventions specifically within primary care.

This review aims to synthesize current evidence on the effectiveness of both psychological and pharmacological treatments for anxiety in primary care settings, comparing them against control conditions. Our focus is on studies conducted in countries with universal healthcare systems, as these settings most closely mirror real-world treatment scenarios where mental health services are routinely available in primary care without significant financial barriers for patients. Regarding psychological treatments, this review seeks to update and expand upon the work of Seekles et al. [17] by: a) prioritizing the identification of studies where treatment was delivered by non-specialists or GPs, and b) excluding studies focusing on obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as these are now classified separately from anxiety disorders in current diagnostic systems. Furthermore, we aim to investigate factors that might influence the effectiveness of psychological treatments, specifically the type of treatment provider (specialist vs. non-specialist) and the treatment modality (face-to-face, online, or self-help).

Method

Search Strategy and Study Selection

This systematic review and meta-analysis adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and was pre-registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42018050659). A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed using MeSH terms (detailed in Table 1). To ensure a broad search, PsycINFO, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), CINAHL, and Scopus were also searched. The complete search strategy for each database is available in Supplementary File 1.

Table 1. MeSH Terms for PubMed Search

| Topic | MeSH Terms |

|---|---|

| Anxiety | “Anxiety Disorders” OR “Anxiety” |

| Primary Care | “Primary Health Care” OR “Physicians, Primary Care” OR “General Practice” OR “General Practitioners” OR “Physicians, Family” OR “Primary Care Nursing” OR “Family Nursing” OR “Nurses, Community Health” OR “Nurse Practitioners” OR “Nurse Clinicians” |

| Treatment (general) | “Outcome Assessment (Health Care)” |

| Treatment (psychological) | “Psychotherapy” OR “Counseling” OR “Relaxation” |

| Treatment (pharmacological) | “Drug Therapy” OR “Psychotropic Drugs” OR “Adrenergic beta-Antagonists” |

Duplicate articles were identified and removed using Endnote software. Two independent researchers (ELP and TH) screened titles and abstracts of retrieved articles to determine if they met the initial eligibility criteria. Full-text versions of potentially eligible studies were then screened by ELP and TH for final inclusion. Reference lists of included articles were manually searched to identify any additional relevant studies, but none were found. Any disagreements between reviewers during each stage were resolved through discussion and consensus.

The initial searches were carried out on April 17, 2017. To capture more recent publications, searches were repeated on April 22, 2020, for studies published since the initial search date. The first author screened these additional records using the same process. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Publication details | Peer-reviewed journal articles reporting primary data Published since 1997 Article written in English |

| Study type | Controlled trials |

| Population | Adults (18 + years) Primary diagnosis of anxiety disorder or clinically significant anxiety Mixed anxiety/depression |

| Setting | Primary care Country with universal healthcare |

| Treatment | Evidence-based psychological or pharmacological treatments for anxiety |

| Outcome | At least one measure of anxiety symptomatology |

To focus on contemporary evidence, we excluded studies published before 1997, setting a cut-off 20 years prior to our initial search. Participants included were adults (18+) with a primary diagnosis of an anxiety disorder based on DSM or ICD criteria, or those exhibiting clinically significant anxiety levels as indicated by assessment/screening tools (e.g., BAI, DASS). Studies of OCD and PTSD were excluded due to their reclassification outside of anxiety disorders. Studies involving mixed anxiety and depression were included if the treatment specifically targeted anxiety (e.g., anxiety-specific pharmacological agents or psychological treatments).

Evidence-based treatments were defined as psychological and pharmacological interventions supported by existing research and consistent with current clinical practice guidelines (e.g., NICE guidelines, [12]). Psychological interventions included self-help, mindfulness/applied relaxation, and individual cognitive behavioral therapy [12, 14, 15]. Pharmacological treatments included SSRIs, SNRIs, pregabalin (for generalized anxiety disorder), tricyclic antidepressants (for panic disorder), and benzodiazepines for short-term use [12, 14, 15].

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The primary outcome of interest was the treatment effect size, measured as the standardized mean difference, for the reduction of anxiety symptoms in each study. Secondary outcomes included treatment effect sizes for depressive symptom reduction and improvements in quality of life. Two independent reviewers (ELP and either TH or DBF) coded included papers using a standardized data extraction form. Extracted variables included participant demographics (age, gender), study country, anxiety disorder type, treatment type, treatment modality (self-help, online, face-to-face), treatment provider, control group type, and outcome statistics (means and standard deviations at post-treatment and follow-up, or alternative statistics if these were unavailable). Data were extracted from published reports, and study authors were contacted to obtain missing information when necessary. Inter-rater agreement was assessed by comparing coding forms after extraction, and disagreements were resolved through discussion and review of the articles.

Standardized mean differences (Hedges’ g) [26] and standard errors were calculated at post-treatment for each study, comparing treatment and control groups. Hedges’ g was chosen as it corrects for small sample sizes [27], relevant to some included studies. Separate effect sizes were calculated for each active treatment arm compared to the control group in studies with multiple treatment arms. When anxiety-specific measures were not the primary outcome, the most appropriate anxiety symptom measure (e.g., gold standard for a disorder, best test-retest reliability) was used. Measures from each study are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3. Characteristics of Included Studies

| First Author, Year | Country | n | FU | Disorder | Outcome | Treatment | Modality | Provider | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Treatment Studies | |||||||||

| Berger, 2017 | Germany/Switzerland/Austria | 139 | 6-mth | Anx | BAI | CBT | Online | Self | CAU |

| Gensichen, 2019 | Germany | 419 | 6-mth | Anx | BAI | CBT | Guided bibliotherapy | GP | CAU |

| Kendrick, 2005 (1) | United Kingdom | 247 | 4-mth | CMD | HADS-A | Other | F2F | Mental health nurse | CAU |

| Kendrick, 2005 (2) | Other | F2F | Mental health nurse | CAU | |||||

| Klein, 2006 (1) | Australia | 55 | 3-mth | Anx | PDSS | CBT | Online | Psychologist | Waitlist |

| Klein, 2006 (2) | CBT | Bibliotherapy | Trainee psychologist | Waitlist | |||||

| Newby, 2013 | Australia | 99 | 3-mth | CMD | GAD-7 | CBT | Online | Unspecified clinician | Waitlist |

| Nordgren, 2014 | Sweden | 100 | 10-mth | Anx | BAI | CBT | Online | Trainee psychologist | Waitlist |

| Power, 2000 (1) | Scotland | 104 | 6-mth | Anx | HAM-A | CBT | Guided (std.) bibliotherapy | Clinical psychologist | CAU |

| Power, 2000 (2) | CBT | Guided (min.) bibliotherapy | Clinical psychologist | CAU | |||||

| Seekles, 2011a | Netherlands | 108 | – | Anx | HADS-A | Other/CBT | Guided online/bibliotherapy | Mental health nurse | CAU |

| Sharp, 2004 (1) | United Kingdom | 97 | 3-mth | Anx | HAM-A | CBT | F2F | Clinical psychologist | Waitlist |

| Sharp, 2004 (2) | CBT | F2F – group | Clinical psychologist | Waitlist | |||||

| Sundquist, 2015 | Sweden | 215 | – | CMD | HADS-A | Other | F2F – group | Psychologist/counsellor | CAU |

| van Boeijen, 2005 | Netherlands | 142 | 10-mth | Anx | STAI-S | CBT | Guided bibliotherapy | GP | CAU |

| Pharmacological Treatment Studies | |||||||||

| Laakmann, 1998 (1) | Germany | 125 | – | Anx | HAM-A | Buspirone | Tablet | GP | Placebo |

| Laakmann, 1998 (2) | Lorazepam | Tablet | GP | Placebo | |||||

| Lader, 1998 (1) | France and United Kingdom | 244 | – | Anx | HAM-A | Hydroxyzine | Tablet | GP | Placebo |

| Lader, 1998 (2) | Buspirone | Tablet | GP | Placebo | |||||

| Lenox-Smith, 2003 | United Kingdom | 244 | – | Anx | HAM-A | Venlafaxine | Tablet | GP | Placebo |

| Llorca, 2002 (1) | France | 334 | – | Anx | HAM-A | Hydroxyzine | Tablet | GP | Placebo |

| Llorca, 2002 (2) | Bromazepam | Tablet | GP | Placebo | |||||

| Combined Treatment and Stepped Care Studies | |||||||||

| Blomhoff, 2001 (1) | United Kingdom | 387 | – | Anx | SPS | Sertraline + CBT | F2F + tablet | GP | Placebo |

| Blomhoff, 2001 (2) | Sertraline | Tablet | GP | Placebo | |||||

| Blomhoff, 2001 (3) | CBT | F2F | GP | Placebo | |||||

| Muntingh, 2014 | Netherlands | 180 | 9-mth | Anx | BAI | Stepped Care | Multiple | Multiple | CAU |

| Oosterbaan, 2013 | Netherlands | 158 | 4-mth | CMD | HAM-A | Stepped Care | Multiple | Multiple | CAU |

| Seekles, 2011b | Netherlands | 120 | – | CMD | HADS-A | Stepped Care | Multiple | Multiple | CAU |

Anx anxiety disorders only, CMD common mental disorders, BAI Beck Anxiety Inventory, GAD-7 Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale, HADS-A Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety Subscale, HAM-A Hamilton Anxiety Scale, PDSS Panic Disorder Severity Scale, SPS Social Phobia Scale, STAI-S State Trait Anxiety Inventory-State Subscale, CBT Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, F2F face-to-face therapy, GP general practitioner, CAU care as usual, FU follow-up length post-treatment, n total n for study

Meta-analysis was performed on psychological treatment studies, while other study types were synthesized using narrative methods. Meta-analysis was conducted using RStudio with the metafor package [28]. For studies with multiple treatment arms, effect sizes for each active treatment compared to control were included. A random-effects multi-level model was used to account for intercorrelation of effect sizes from the same study, and meta-regression analyses explored moderator variables. Code for these analyses was obtained from the metafor package website (www.metafor-project.org) based on descriptions of meta-analysis for multiple treatment studies [29] and multivariate random and mixed-effects models [30]. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using Chi2 tests and I2 estimates, with I2 interpretation based on Cochrane handbook guidelines [31]. Meta-regression was used to explore heterogeneity through moderator variables.

Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s regression test of funnel plot asymmetry [32, 33] using sampling variance as a moderator in a multi-level model. Sensitivity analysis, limited for multivariate/multi-level models [34], was conducted using Cook’s distance [35, 36] to identify influential outliers, defined as observations with a Cook’s distance > 4/n.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Risk of bias for each study was independently assessed by ELP and DBF using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool [37]. Blinding of participants and personnel is often not feasible in psychological treatment studies. In such cases, studies were rated as “unclear” risk of bias for this criterion unless other factors warranted a “high” rating. Consistent with similar reviews of heterogeneous studies [38], reviewers reached agreement on all items through discussion and consensus.

Results

Study Characteristics

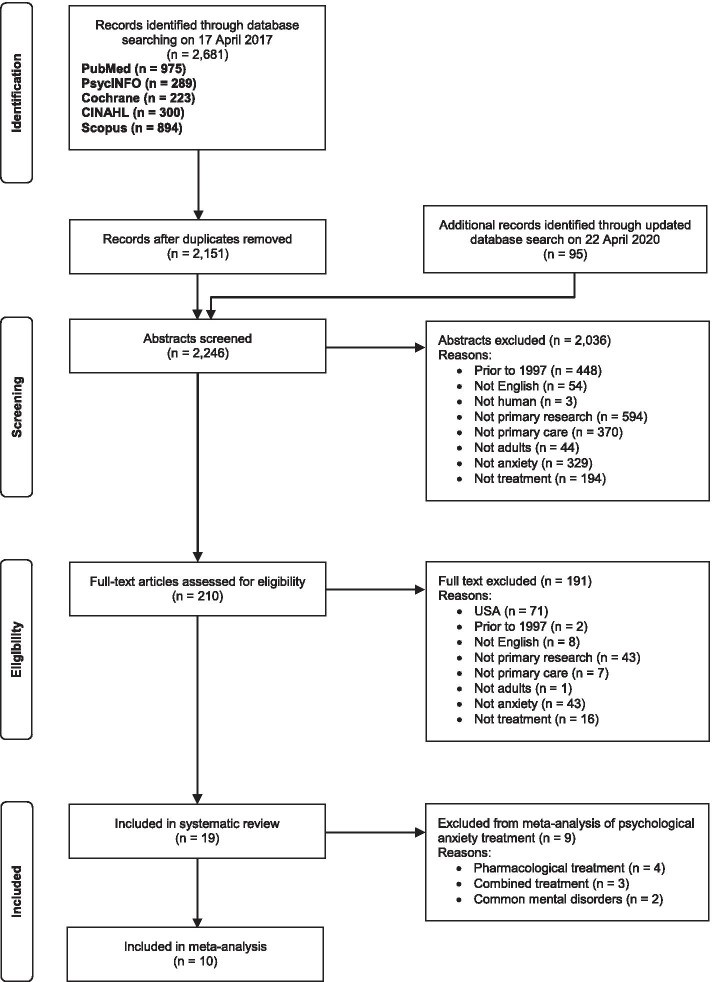

Initial searches yielded 2,151 articles after removing duplicates, with 207 full-text articles screened. Eighteen articles reporting 17 studies met all inclusion criteria. Inter-rater agreement for extracted variables was 89.3%. Updated searches in April 2020 identified one additional study from 95 articles published since the original search. Of 191 articles excluded after full-text screening, 71 were excluded for being conducted in countries without universal healthcare, all from the USA, including 31 publications from a single large collaborative care study for anxiety [39]. The study selection process is detailed in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram of Study Selection

In total, 19 articles reporting 18 studies were included. Two articles reported separate steps of the same study [40, 41], and eight studies included multiple active treatment conditions [19, 42–49]. Across all studies, there were 28 comparisons of active treatment with a control group (placebo, waitlist, or care as usual [CAU]). Key characteristics of included studies are in Table 3.

Participant Demographics and Clinical Profiles

The included studies randomized 2,059 participants to active treatment and 1,247 to control conditions. Participant age ranged from 18 to 80 years, with mean ages across studies ranging from 34.2 to 51 years. All studies had a higher proportion of female participants.

Thirteen studies focused specifically on anxiety disorders: generalized anxiety disorder (4 studies), panic disorder (4 studies), and multiple anxiety disorders (5 studies, including mixed anxiety/depression). Five studies included participants with “common mental disorders” (anxiety, depression, stress, and adjustment disorders). One study reported separate outcomes for anxiety-only participants [40], and anxiety-only data was obtained from authors for another [43].

Most studies reported moderate mean anxiety severity at baseline, using clinician-rated (e.g., CGI-S, HAM-A) or self-report (e.g., BAI) measures. Two studies reported mild-to-moderate baseline anxiety [41, 43], and five reported moderate-severe or severe anxiety [19, 44, 45, 50, 51].

Treatment and Control Group Characteristics

Psychological treatment studies were the most common (10/18, 55.5%). Four studies investigated pharmacological treatments (22.2%), and one compared psychological and pharmacological treatments. Three studies examined stepped care, including both types of treatments. Pharmacological studies were generally older (1998-2003) than psychological studies (2000-2019).

Among the 10 psychological treatment studies, four used a waitlist control and six used CAU. Control group care was described in four CAU-controlled studies [19, 48, 50, 52], commonly including antidepressants, benzodiazepines, CBT, or specialist mental health referral. Most control participants received at least one of these, although specific numbers for each care type were not consistently reported, except for one study [50]. All three stepped care studies used CAU controls and described control group care, with at least half receiving medication, specialist referral, or both. All pharmacological treatment studies used placebo controls.

Psychological Interventions: Focus on CBT and Delivery Modality

Four psychological treatment studies examined two different treatments versus control. Including the psychological arm of the combined treatment study [42] and the self-help step of a stepped care study [40, 41], there were 16 comparisons of psychological treatment with CAU or waitlist control.

CBT-based treatments were predominant (n=13, 81.2% of 16) and mainly individual. One study used group treatment [52], and another compared individual and group treatment [49]. Delivery was face-to-face (n=6, 37.5%) or via self-help manuals/internet with professional support (n=10, 62.5%). Specialists (clinical psychologists or psychologists) provided treatment in six conditions (37.5%). Non-specialists provided treatment in ten conditions: trainee psychologists (n=2), mental health nurses (n=3), GPs (n=3), unspecified clinicians (n=1), and self-guided (n=1).

Efficacy of Psychological Treatments for Anxiety Disorders

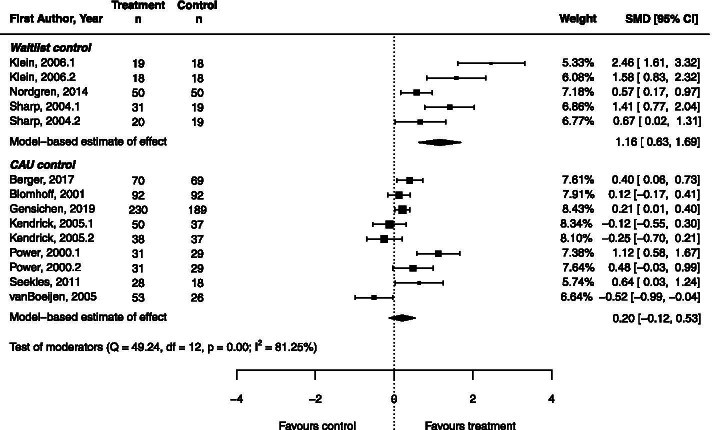

Meta-analysis was conducted on psychological treatment studies focusing solely on anxiety disorders, excluding studies of common mental disorders and mixed anxiety/depression to reduce heterogeneity [43, 53]. Narrative synthesis is used below for common mental disorders. The meta-analysis included 14 comparisons of psychological treatment versus control from ten studies (Figure 2, Table 4). Results showed a large pooled effect size for psychological treatment compared to waitlist control (g = 1.16, 95%CI = 0.63 – 1.69), but no significant effect compared to CAU (Z = 1.21, p = 0.225). Substantial heterogeneity was present (I2 = 81.25).

Fig. 2. Forest Plot of Psychological Treatments vs. Control for Anxiety Disorders

Table 4. Meta-Analytic Results for Psychological Treatment of Anxiety Symptoms

| n | g | se | 95% CI | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies | 14 | 0.49 | 0.20 | 0.10 – 0.88 | 2.44 | .015 |

| Treatment vs. CAU | 9 | 0.20 | 0.17 | -0.12 – 0.53 | 1.21 | .225 |

| Treatment vs. waitlist | 5 | 1.16 | 0.27 | 0.63 – 1.69 | 4.28 | |

| Non-specialist provider | 9 | |||||

| CAU control | 7 | 0.10 | 0.13 | -0.16 – 0.35 | 0.73 | .468 |

| Waitlist control | 2 | 0.80 | 0.25 | 0.31 – 1.28 | 3.22 | .001 |

| Specialist provider | 5 | |||||

| CAU control | 2 | 0.76 | 0.25 | 0.27 – 1.25 | 3.04 | .002 |

| Waitlist control | 3 | 1.46 | 0.26 | 0.96 – 1.96 | 5.71 |

n number of comparisons in analysis, se standard error, CAU care as usual

Treatment provider was investigated as a moderator variable. Meta-regression showed that treatment effect was significantly moderated by provider type (z = 2.61, p = 0.009), accounting for 53% of heterogeneity. However, residual heterogeneity remained significant (QE = 36.22, df = 11, p < 0.001).

Non-specialist treatment did not significantly improve anxiety symptoms compared to CAU (p = 0.468), but showed a large effect compared to waitlist control (g = 0.80, 95%CI = 0.31 – 1.28). Specialist-provided treatment showed large effects against both CAU (g = 0.76, 95%CI = 0.27 – 1.25) and waitlist (g = 1.46, 95%CI = 0.96 – 1.96).

Egger’s regression test indicated significant funnel plot asymmetry (z = 3.70, p < 0.001), suggesting publication bias. Sensitivity analysis identified one influential outlier study [19] with a Cook’s distance of 0.23, close to the threshold of 0.29 (4/n), indicating a larger model influence.

Narrative Synthesis of Psychological Treatments for Common Mental Disorders

One study examined problem-solving and generic mental health nurse care for common mental disorders and found no significant treatment effect compared to CAU [43]. Anxiety-only data from this study was included in the meta-analysis above. Another study on online CBT for mixed anxiety and depression found a large effect size (g = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.43 – 1.27) compared to waitlist control [53].

Pharmacological Interventions in Primary Care

All four pharmacological studies investigated medications for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), with three comparing two medications. There were eight comparisons of pharmacological treatment to placebo, including the pharmacological arm of a combined treatment study for generalized social phobia [42]. Meta-analysis was not feasible due to incomplete outcome statistics in primary articles.

Two benzodiazepine-placebo comparisons [45, 47] showed no significant difference at post-treatment. Two studies [45, 46] also reported no buspirone effect over placebo. Hydroxyzine showed significant treatment effects in both comparisons to placebo; one reported a moderate effect size (g = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.16 – 0.78) [46], and the other a similar effect (g = 0.32, 95% CI = 0.05 – 0.60) [47]. SSRI/SNRI medications also showed treatment effects; sertraline had a small effect (g = 0.29, 95% CI = 0.00 – 0.58) versus placebo [42], and venlafaxine showed a small effect (g = 0.25, 95% CI = 0.00 – 0.50) versus placebo [51].

Combined and Stepped Care Interventions

Meta-analysis was not performed on combined interventions due to limited studies and clinical diversity. A single study on combined psychological and pharmacological treatment compared exposure therapy, sertraline, and their combination to placebo [42]. Psychological and pharmacological treatment results are reported above. Combined treatment also showed a significant effect versus control (g = 0.35, 95% CI = 0.07 – 0.64), but was not significantly different from either treatment alone.

Three stepped care studies [41, 54, 55] involved multiple professionals, including mental health nurses and psychiatrists, with higher steps including medication and psychological therapy. Two studies found small, significant stepped care effects compared to CAU for common mental disorders (g = 0.23, 95%CI = -0.13 – 0.58 [41]; g = 0.31, 95%CI = -0.01 – 0.63 [55]). One study on stepped care for anxiety only also found a significant effect (g = 0.21, 95%CI = -0.12 – 0.54) [54].

Long-Term Follow-Up of Anxiety Treatment Outcomes

Eleven of 18 included studies reported follow-up data (≥3 months post-treatment), but synthesis was challenging due to reporting variability. Narrative methods are used below.

All but one psychological treatment study [52] reported follow-up. Waitlist control studies showed maintained treatment gains at 3- [44, 53] and 10-month [56] follow-up within the treatment group (control data not recorded as they received intervention post-waiting). One study comparing group and individual CBT reported maintained gains in group CBT but decreased clinically significant change in individual CBT at follow-up [49].

Among CAU-controlled studies, four reported follow-up outcomes for both groups. Two showed no significant difference between groups [19, 43], with no significant score changes in any group from post-treatment to follow-up. One study reported a follow-up effect size of g = 0.31 (95%CI = 0.08 – 0.53, p = 0.01) for self-help CBT vs. control [50], and another reported maintained clinically significant change rates from post-treatment [48]. One study reported sustained treatment gains in assessed treatment group participants [57].

Two of four stepped care studies reported follow-up; one reported an effect size of g = 0.37 (95%CI = 0.02 – 0.72, p = 0.04) for stepped-care vs. CAU [54], and the other reported maintained gains within the treatment group but no significant stepped-care effect vs. CAU due to control group improvements at follow-up [55]. Pharmacological treatment studies did not report follow-up data.

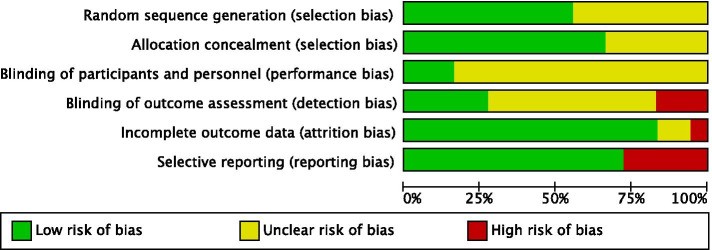

Risk of Bias Assessment Across Studies

Most included studies had unclear risk of bias in one or more key domains (Figure 3 and 4). Inter-rater agreement for risk of bias was 85.3%. Psychological and combined treatment studies often had unclear performance bias due to lack of participant blinding and detection bias due to self-report measures or unblinded assessors. Reporting bias was low for these studies, and selection bias was low-to-unclear. Most studies reported similar dropout rates across conditions and used intention-to-treat analyses.

Fig. 3. Risk of Bias Assessment for Each Study

Fig. 4. Summary of Risk of Bias Items Across All Studies

Pharmacological treatment studies generally had unclear-to-high risk of bias across domains. All four studies reported inadequate information on randomization and allocation concealment. Three had high risk of selective outcome reporting, presenting results visually without statistics. Three studies were pharmaceutical company funded [46, 47, 51] and none included conflict of interest statements.

Secondary Outcomes: Depressive Symptoms and Quality of Life

Most studies (n=15, 83.3%) measured depressive symptoms, often as secondary or combined primary outcomes. Most of these (n=8) found no significant difference in depressive symptoms between groups. Seven studies reporting significant treatment effects on depression showed effect sizes from g = 0.35 to 1.00.

Less than half of studies (n=7, 38.8%) measured quality of life. Three found no significant group differences, and four reported significant treatment effects ranging from g = 0.31 to 1.36.

Discussion

This review synthesized evidence for psychological and pharmacological treatments for anxiety, focusing on the impact of treatment provider on psychological treatment efficacy in primary care. Psychological treatment studies were diverse, broadly categorized into those for specific anxiety disorders and those for common mental disorders.

Meta-analysis confirmed that psychological treatments, predominantly CBT, are effective in reducing anxiety symptoms in primary care for individuals with primary anxiety disorders. However, the extent of improvement varies by treatment provider and comparison group. Specialist-provided treatment shows significant symptom reduction regardless of the control group type, although the effect size is smaller when compared to usual care versus waitlist control. Non-specialist treatment is also effective compared to no treatment (waitlist control) but not superior to usual care. These findings align with prior reviews indicating greater efficacy for specialist-delivered interventions [23]. Existing research also shows smaller effect sizes for both face-to-face and computerized CBT when compared to active control conditions like CAU versus inactive controls [20, 23].

CBT is well-established as effective for anxiety [13, 23], but more research is needed on long-term primary care effectiveness. In this review, CBT was mostly delivered via bibliotherapy or computer-based methods with varying clinician support. Self-help CBT effectiveness is supported by other reviews [20, 21], and our results support its implementation in primary care. Computerized CBT offers high fidelity, delivering interventions as designed, unlike face-to-face therapy where provider experience and adherence to manuals can vary, particularly for non-specialists [13].

Follow-up results in psychological treatment studies were mixed. However, most studies reported maintained treatment gains within the treatment group, superior to usual care control groups. Limited long-term data is a general limitation, though non-primary care studies suggest psychological treatment effects for anxiety are generally well-maintained [59, 60].

Narrative synthesis of common mental disorder treatment studies showed similar patterns to anxiety-specific studies: psychological treatments were not significantly better than CAU, but showed large effects compared to waitlist control.

Pharmacological treatment studies were limited, with only two [42, 51] involving current first-line anxiety agents (sertraline and venlafaxine) [12]. Both showed small, superior effects to placebo, indicating effectiveness in primary care. Hydroxyzine also showed small to moderate effects in three studies, while buspirone and benzodiazepines did not outperform placebo. However, hydroxyzine and buspirone are not first-line agents, and benzodiazepines are only recommended in specific situations like SSRI initiation [61]. Furthermore, most pharmacological studies were pharmaceutical-funded and had high risk of bias, raising concerns about result validity. Overall, strong research evidence for pharmacological treatments in primary care was lacking, even considering the exclusion of non-universal healthcare country studies.

Pharmacological studies lacked long-term follow-up data, limiting assessment of effectiveness beyond acute treatment. Relapse risk is known to be high after discontinuing pharmacological interventions post-acute treatment, necessitating 6-24 months of continued treatment post-remission [62]. Given the prevalence of pharmacological treatment in primary care, more research is crucial to determine its effectiveness in this setting.

Combined medication and psychological therapy was directly studied in only one trial [42], showing combined treatment effectiveness versus control but no superiority over either treatment alone. Despite common combined treatment use, evidence for better outcomes is limited [13]. Stepped care interventions, including both treatment types, appear effective for anxiety based on three included studies, consistent with emerging evidence for collaborative stepped care in primary care, showing small to moderate effect sizes in prior reviews [63].

Limitations of the Current Evidence Base

This review has several limitations. Study heterogeneity requires cautious interpretation of meta-analytic results. Heterogeneity may stem from mixed self-report and clinician measures, varied treatment modalities (online, face-to-face, group), and inclusion of multiple anxiety disorders, potentially with differential treatment responses. Limited study numbers prevented exploration of additional moderators, including treatment modality. Pooling heterogeneous studies, while statistically and theoretically complex, may reflect real-world primary care diversity. While combining diverse interventions limits conclusions about individual intervention effects, it can address broader questions, such as summarizing drug class effects [31]. Despite heterogeneity limitations, findings contribute to understanding psychological intervention effectiveness for anxiety in primary care.

Another limitation is the interpretability of psychological treatment effects compared to CAU, given the poor CAU descriptions in included studies. Control participants’ care could range from medication to psychological treatments, general advice, or no treatment, with most studies not reporting care type frequencies. However, studies indicated at least half of control participants received some active intervention, including specialist referral and antidepressants, potentially reducing the apparent effectiveness of non-specialist treatments, as control participants may have received higher intensity treatments.

Like all systematic reviews, our search strategy and inclusion criteria may have missed relevant primary care anxiety treatment studies, especially those from non-universal healthcare countries (USA) and non-English publications. The limited number of primary care-specific pharmacological treatment studies might have been expanded with searches of additional biomedical databases (e.g., Embase), which were not accessible for this review.

Despite efforts to identify non-specialist provider studies, relatively few studies of GP-delivered psychological treatments were found. Combined with limited pharmacological treatment studies, the identified evidence base is inconsistent with real-world primary care anxiety disorder treatment [6, 11], limiting our ability to describe treatment effectiveness. Generalizability to low-income and non-universal healthcare high-income countries is also limited. Finally, only one study directly compared medication and psychological treatment in primary care, hindering comments on their relative effectiveness. Other reviews note the lack of psychological vs. pharmacological treatment comparisons as a significant limitation, particularly for computerized CBT vs. medication [20].

Implications for Primary Care Practice and Diagnosis

Despite limitations, this review has key implications for primary care. Results reinforce prior research supporting CBT-based psychological treatments for anxiety and the preference for specialist-provided treatment [23]. Our findings extend previous work by providing data on non-specialist treatment, crucial given limited specialist access in primary care. While non-specialist psychological treatment was not superior to usual care, it was not inferior, suggesting it is at least as effective as usual treatments and a suitable option. Moreover, non-specialist treatment significantly improved anxiety compared to no treatment.

Although pharmacological treatments are generally effective for anxiety [61] and offer cost and accessibility advantages, strong evidence for their primary care use is lacking due to limited studies and high risk of bias. Anxiety medications carry side effects [64], and benzodiazepines, still commonly prescribed despite not being first-line [24, 25], pose physiological and psychological dependence risks. Benzodiazepines may prolong anxiety if used alone, acting as safety behaviors and potentially impairing fear extinction [65, 66], especially when physiological anxiety symptoms are the feared stimuli, as in panic disorder.

We recommend cautious pharmacological treatment use in primary care pending further research and suggest CBT-based psychological treatments, including online and self-help options, as first-line anxiety disorder treatments. Specialist delivery is preferred if available and affordable. However, non-specialists should offer psychological treatment when specialist care is not feasible.

Conclusions

This review highlights the need for better alignment between research and practice in managing anxiety disorders in universal healthcare systems. More research is needed on primary care pharmacological treatment and its comparative effectiveness to psychological interventions. Future psychological treatment research should better reflect real-world primary care delivery (treatment provider types). Implementation science, including provider and patient perspectives, should explore barriers to psychological treatment delivery for anxiety in primary care.

Supplementary Information

12875_2021_1445_MOESM1_ESM.docx (15.2KB, docx) Additional file 1. Additional Table. Full Search Strategy. Full search strategy used for all databases.

Acknowledgements

The first author conducted this review as part of a PhD in Clinical Psychology at the Australian National University (ANU), under the supervision of the second, third, and last authors. We thank Professor Philip Batterham for his contributions.

Abbreviations

BAI Beck anxiety inventory

CAU Care as usual

CBT Cognitive behaviour therapy

DASS Depression anxiety stress scale

DSM Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

GAD Generalised anxiety disorder

GP General practitioner

ICD International classification of diseases

OCD Obsessive compulsive disorder

PTSD Post-traumatic stress disorder

SNRI Serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors

SSRI Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

Authors’ contributions

ELP, MB, DBF, and MK conceptualized and designed the study. ELP and TH assessed study eligibility. ELP and TH or DBF extracted data. ELP conducted analyses, and ELP, MB, and DBF interpreted data. ELP drafted the article, and all authors critically revised and approved the final version.

Funding

This research received no specific funding. ELP was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (AGRTP) Stipend Scholarship. MB is supported by a Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) TRIP Fellowship MRF1150698, unrelated to this work. Funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or report writing.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed are included in this article, its supplementary files, and the cited published articles.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not required for this systematic review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

ELP is paid by Marathon Health for psychological therapy and has a private psychology practice. No other conflicts of interest are declared.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral on jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[References listed in the original article should be included here, maintaining the original numbering and links]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

12875_2021_1445_MOESM1_ESM.docx (15.2KB, docx) Additional file 1. Additional Table. Full Search Strategy. Full search strategy used for all databases.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article, its additional files, and the published articles included in this review.