Portal hypertension, characterized by elevated pressure in the portal venous system, is a significant clinical challenge, especially in patients with liver cirrhosis. As experts at xentrydiagnosis.store, understanding the Diagnosis Of Portal Hypertension is crucial for automotive technicians, as it highlights the complexity of systemic conditions that can impact overall health. This article provides an in-depth guide to diagnosing portal hypertension, aiming to surpass the original content in comprehensiveness and SEO value for English-speaking professionals.

Introduction

Portal hypertension is defined by an increased portal pressure gradient (PPG), which is the difference in pressure between the portal vein and the inferior vena cava or hepatic vein. Normally, this gradient is ≤ 5 mmHg. A PPG ≥ 6 mmHg is indicative of portal hypertension in most cases.[1] Clinically significant portal hypertension arises when the PPG exceeds 10 mmHg, while a gradient between 5 to 9 mmHg often represents a subclinical stage. The hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) is the standard measurement for assessing PPG.[1] Portal hypertension occurs due to increased resistance to portal blood flow, commonly within the liver as seen in cirrhosis, but also potentially pre-hepatic (e.g., portal vein thrombosis) or post-hepatic (e.g., constrictive pericarditis, Budd-Chiari syndrome). Identifying the location of resistance is key to diagnosing the cause of portal hypertension. This condition is a major driver of hospitalization, variceal bleeding, liver transplantation, and mortality in cirrhotic patients. The term “portal hypertension” was first introduced by Gilbert and Carnot in 1902.

Etiology of Portal Hypertension

Diagnosing portal hypertension effectively requires understanding its diverse etiologies. These are broadly categorized into prehepatic, intrahepatic, and posthepatic causes.

Prehepatic Causes: These are related to increased portal blood flow or obstruction in the portal or splenic veins. Increased flow can result from conditions like idiopathic tropical splenomegaly or arteriovenous malformations. Obstruction can be due to portal or splenic vein thrombosis, tumor invasion, or compression.[1]

Intrahepatic Causes: These are further divided into pre-sinusoidal, sinusoidal, and post-sinusoidal categories.

- Pre-sinusoidal: Include schistosomiasis, congenital hepatic fibrosis, early primary biliary cholangitis, sarcoidosis, chronic active hepatitis, and exposure to toxins such as vinyl chloride, arsenic, and copper.

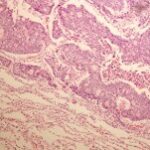

- Sinusoidal: Primarily caused by cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis, vitamin A toxicity, and certain cytotoxic drugs.

- Post-sinusoidal: Result from sinusoidal obstruction syndrome or veno-occlusive disease.[1]

Posthepatic Causes: These originate from obstructions at the level of the heart, hepatic veins (as in Budd-Chiari syndrome), or the inferior vena cava. Cardiac causes involve elevated atrial pressure, such as in constrictive pericarditis. Inferior vena cava obstructions may arise from stenosis, thrombosis, webs, or tumor invasion.[1]

Epidemiology of Portal Hypertension

In diagnosing portal hypertension, epidemiological context is important. Liver cirrhosis is the leading cause in Western countries. However, schistosomiasis is the most prevalent cause worldwide, especially in regions where it is endemic, such as Africa.[1] Understanding these epidemiological differences can guide diagnostic considerations based on patient demographics and geographical location.

Pathophysiology of Portal Hypertension

The pathophysiology of portal hypertension is crucial for accurate diagnosis. The portal vein, formed by the superior mesenteric and splenic veins, delivers blood to the liver. Normally, portal vein pressure is only slightly higher (1-4 mmHg) than hepatic vein pressure, facilitating blood flow through the liver into systemic circulation. The absence of valves in these veins means that increased resistance to flow in the portal venous system directly elevates portal venous pressure, leading to portal hypertension. This resistance is most commonly intrahepatic, as seen in cirrhosis, but can also be pre- or post-hepatic.

Increased intrahepatic resistance can stem from both structural and dynamic changes. Structural changes involve hepatic microcirculation alterations due to hepatic stellate cell activation, fibrosis, regenerative nodules, vascular occlusion, and angiogenesis. Dynamic changes involve sinusoidal constriction due to increased vasoconstrictors and decreased vasodilators within the liver.[2] The condition is further exacerbated by increased splanchnic blood flow, driven by splanchnic vasodilation from increased shear stress and reduced effective arterial volume. Therefore, portal hypertension is a consequence of both increased resistance to portal flow and increased portal blood flow due to splanchnic vasodilation. Elevated portal pressure triggers the development of collateral vessels as the body attempts to reduce pressure.[2]

History and Physical Examination in Diagnosing Portal Hypertension

Diagnosis often begins with recognizing clinical signs and symptoms. Initially, patients may be asymptomatic until complications manifest. Hematemesis from variceal bleeding is a common presenting symptom. Melena may also occur. Given that cirrhosis is a major cause, patients might exhibit stigmata of cirrhosis, including jaundice, gynecomastia, palmar erythema, spider nevi, testicular atrophy, ascites, pedal edema, and asterixis due to hepatic encephalopathy.[3]

Prominent abdominal wall veins may be observed, representing collateral circulation via paraumbilical veins. In caput medusae, blood flow is directed away from the umbilicus, whereas in inferior vena cava obstruction, flow is towards the umbilicus. A venous hum may be auscultated near the xiphoid process or umbilicus.[4] Cruveilhier-Baumgarten syndrome is characterized by dilated abdominal veins and a venous murmur at the umbilicus. An arterial systolic murmur might indicate hepatocellular carcinoma or alcoholic hepatitis.[4] Splenomegaly is a significant diagnostic sign of portal hypertension.[1] Its absence should prompt reconsideration of the diagnosis. Pancytopenia associated with hypersplenism is due to reticuloendothelial hyperplasia and is not reversed by portal pressure reduction. While a firm liver can suggest cirrhosis, hepatomegaly does not correlate with portal hypertension severity.

Evaluation and Diagnostic Procedures for Portal Hypertension

Effective diagnosis of portal hypertension involves a combination of patient history, physical examination, and specific diagnostic tests.

Laboratory Tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Helps identify thrombocytopenia (due to hypersplenism) and anemia (from gastrointestinal bleeding).

- Complete Metabolic Panel (CMP): Assesses renal function, liver enzyme levels (elevated in liver disease or hepatitis), and hypoalbuminemia.

- Coagulation Profile: Evaluates liver synthetic function. Prolonged prothrombin time and low serum albumin are strong indicators of impaired hepatic synthesis.

Imaging Studies:

- Doppler Ultrasound of the Portal Vein: Detects stenosis or thrombosis, and assesses portal vein flow direction (hepatopetal – towards the liver, or hepatofugal – away from the liver), which varies with portal hypertension severity. Hepatopetal flow is normal.

- Abdominal Ultrasound: Identifies signs of cirrhosis, ascites, and splenomegaly.[5]

- Endoscopy: Essential for detecting varices.

- Paracentesis: Required for patients with ascites to determine etiology and rule out spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.[6, 7]

- Duplex Doppler Ultrasound, Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA), or Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA): Assess the patency of portal and hepatic veins.

Portal Pressure Measurement:

Direct portal pressure measurement is invasive and complex, often unnecessary for diagnosis when clinical signs are evident. Indirect methods are preferred.

- Direct Method: Cannulation of the hepatic vein to measure free hepatic vein pressure.

- Indirect Method: Balloon occlusion of the hepatic vein to measure wedged hepatic vein pressure (WHVP). The HVPG is then calculated using these measurements.[1]

Treatment and Management Strategies Post-Diagnosis

Management following the diagnosis of portal hypertension is etiology-dependent. Reversible causes should be addressed. For instance, anticoagulation is necessary for portal vein or inferior vena cava thrombosis due to hypercoagulable states.

Further treatment focuses on managing complications. For cirrhotic patients, variceal screening via endoscopy is crucial. If large varices or high-risk varices are found, therapy with non-selective beta-blockers and/or endoscopic variceal ligation should be initiated.[8] Acute variceal bleeding requires endoscopic therapy or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement, along with prophylactic antibiotics against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.[9] Ascites management depends on liver disease severity and treatment response, involving dietary sodium restriction, diuretics (spironolactone with furosemide), large-volume paracentesis, TIPS, and potentially liver transplantation.[10] Liver transplantation is the definitive treatment for portal hypertension caused by cirrhosis.

Differential Diagnosis of Portal Hypertension

Differential diagnosis is vital in accurately diagnosing portal hypertension. Conditions to consider include:

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

- Cirrhosis

- Constrictive pericarditis

- Myeloproliferative disease

- Polycystic kidney disease

- Sarcoidosis

- Tricuspid regurgitation

- Tuberculosis

- Vitamin A deficiency

- Wilson disease

Prognosis of Portal Hypertension

Prognosis is highly dependent on the underlying cause of portal hypertension. Early and accurate diagnosis, followed by appropriate management, can significantly impact patient outcomes.

Complications of Portal Hypertension

Understanding potential complications is crucial for comprehensive diagnosis and management:

- Thrombocytopenia

- Abdominal wall collaterals

- Variceal bleeding (gastroesophageal, anorectal, retroperitoneal, stomal)

- Acute bleeding or iron deficiency anemia (portal hypertensive gastropathy, enteropathy)

- Ascites

- Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

- Hepatic hydrothorax

- Hepatorenal syndrome

- Hepatic encephalopathy

- Hepatopulmonary syndrome

- Portopulmonary hypertension

- Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy

Consultations for Portal Hypertension Management

Effective management often requires interdisciplinary consultation, including specialists in:

- Gastroenterology

- Hepatology

- Nephrology

Deterrence and Patient Education for Portal Hypertension

Patient education is a critical aspect of managing portal hypertension. Patients need to be informed about the risks of alcohol consumption, a major cause of cirrhosis, and the potential complications of portal hypertension. Early awareness and proactive medical care seeking can improve outcomes and reduce morbidity and mortality.

Pearls and Key Considerations in Diagnosing Portal Hypertension

- Cirrhosis is the most common cause in Western countries, while schistosomiasis and portal vein thrombosis are more prevalent in other regions.

- Portal hypertension can be asymptomatic until complications arise.

- HVPG measurement and abdominal imaging are essential for diagnosis and etiology determination.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes in Portal Hypertension

Managing portal hypertension necessitates a multidisciplinary approach. An interprofessional team, including nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, primary care physicians, gastroenterologists, hepatologists, transplant teams, and potentially cardiologists and pulmonologists, is essential for comprehensive care. Pharmacists ensure medication accuracy and compliance. Nurses monitor patient vitals and detect changes in status. Clinicians provide regular follow-up, ensuring vaccinations, screenings, and addressing diet, medication, and mental health. Effective interprofessional collaboration is crucial to minimize morbidity and mortality associated with portal hypertension. [Level 5]

References

1.Berzigotti A, Seijo S, Reverter E, Bosch J. Assessing portal hypertension in liver diseases. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Feb;7(2):141-55. [PubMed: 23363263]

2.García-Pagán JC, Gracia-Sancho J, Bosch J. Functional aspects on the pathophysiology of portal hypertension in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2012 Aug;57(2):458-61. [PubMed: 22504334]

3.Schuppan D, Afdhal NH. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2008 Mar 08;371(9615):838-51. [PMC free article: PMC2271178] [PubMed: 18328931]

4.Hardison JE. Auscultation of the Liver. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd ed. Butterworths; Boston: 1990. [PubMed: 21250262]

5.Tchelepi H, Ralls PW, Radin R, Grant E. Sonography of diffuse liver disease. J Ultrasound Med. 2002 Sep;21(9):1023-32; quiz 1033-4. [PubMed: 12216750]

6.Diaz KE, Schiano TD. Evaluation and Management of Cirrhotic Patients Undergoing Elective Surgery. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019 Jun 15;21(7):32. [PubMed: 31203525]

7.Alukal JJ, Thuluvath PJ. Gastrointestinal Failure in Critically Ill Patients With Cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019 Aug;114(8):1231-1237. [PubMed: 31185004]

8.Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2017 Jan;65(1):310-335. [PubMed: 27786365]

9.Chavez-Tapia NC, Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Tellez-Avila F, Soares-Weiser K, Mendez-Sanchez N, Gluud C, Uribe M. Meta-analysis: antibiotic prophylaxis for cirrhotic patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding – an updated Cochrane review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Sep;34(5):509-18. [PubMed: 21707680]

10.Pedersen JS, Bendtsen F, Møller S. Management of cirrhotic ascites. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015 May;6(3):124-37. [PMC free article: PMC4416972] [PubMed: 25954497]