Introduction

Lumbar radiculopathy is a prevalent condition frequently encountered and assessed by spine specialists. Affecting an estimated 3% to 5% of the general population, it impacts both genders, with the likelihood increasing with age due to spinal column degeneration. Typically, the onset of symptoms occurs in middle age, with men commonly experiencing issues in their 40s and women in their 50s and 60s [1, 2]. Certain demographics, such as women in physically demanding occupations like military service, face a heightened risk. However, overall, men exhibit a slightly higher incidence in the broader population [3]. Degenerative spondyloarthropathies stand out as the primary cause of lumbar radiculopathy [1]. Patients often report back pain alongside the characteristic radicular pain. Radiculopathy is defined by pain that radiates into the legs, frequently described as sharp, burning, or electric. The fundamental cause is often irritation of a specific nerve, which can occur at any point along its path, most commonly due to compression. In lumbar radiculopathy, this compression may occur within the thecal sac, at the lateral recess as the nerve root exits, in the neural foramina, or even after exiting the foramina. This compression can be attributed to disc bulges or herniations, facet or ligamentous hypertrophy, spondylolisthesis, or even, in rarer cases, neoplastic and infectious processes. Accurate diagnosis of the underlying cause is crucial and begins with a thorough physical examination, which is the cornerstone for effective management and treatment strategies.

Diagnostic Evaluation of Lumbar Radiculopathy

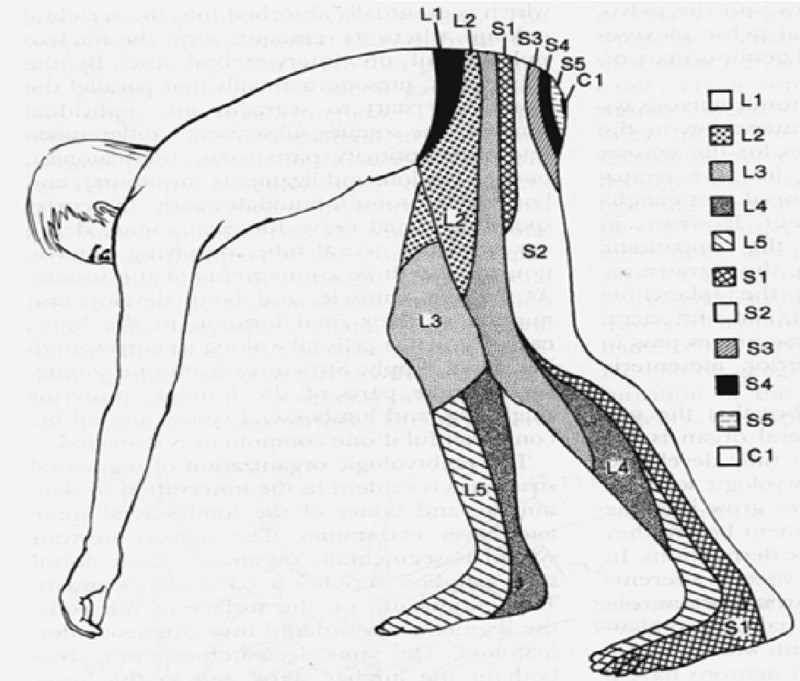

The initial diagnostic process for lumbar radiculopathy necessitates a detailed patient history and a comprehensive physical examination. This includes manual muscle strength testing, sensory assessments, deep tendon reflex evaluation, and the Lasegue’s sign test [4]. Lasegue’s sign, also known as the straight leg raise test, is performed with the patient supine, knee extended, ankle dorsiflexed, and cervical spine slightly flexed. The examiner then lifts the patient’s leg towards 90 degrees, which typically provokes radicular pain if nerve root irritation is present due to nerve stretching. Classically, radiculopathy stemming from nerve root compression manifests as sensory loss in a dermatomal pattern (Figure 1). Motor weakness may follow a myotomal distribution (Table 1). The patterns of pain and motor deficits identified during the physical exam are crucial in guiding the neurosurgeon to pinpoint the affected spinal region, directing the need for advanced diagnostic modalities like MRI and electrodiagnostic studies.

Figure 1. Dermatome Map for Radiculopathy Diagnosis

Anatomical representation of sensory dermatomes in the Lumbosacral region, essential for diagnosing radiculopathy.

Image courtesy of the National University of Córdoba.

Table 1. Lumbosacral Myotome Distribution in Radiculopathy

| Spinal Nerve | Myotome |

|---|---|

| L2 | Hip Flexion (Iliopsoas) |

| L3 | Knee Extension (Quadriceps Femoris) |

| L4 | Ankle Dorsiflexion (Tibialis Anterior) |

| L5 | Ankle Eversion (Peroneus Longus and Brevis), Great Toe Extension (Extensor Hallucis Longus) |

| S1 | Plantar Flexion (Gastrocnemius, Soleus) |

Anatomical distribution of lumbosacral myotomes, crucial for motor function assessment in radiculopathy diagnosis.

Following a thorough physical examination, diagnostic imaging plays a pivotal role in confirming the diagnosis of lumbar radiculopathy. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine, without contrast, is the preferred imaging modality. MRI excels in visualizing soft tissues and can clearly demonstrate nerve root compression (Figure 2). Contrast-enhanced MRI may be indicated in specific scenarios, such as suspected tumors, infections, or in patients with a history of prior spinal surgery. When MRI is not feasible or available, a CT myelogram serves as a viable alternative, offering detailed bony anatomy and spinal canal visualization.

Figure 2. MRI Findings in Lumbar Radiculopathy Diagnosis

A. Sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the lumbar spine without contrast showing a substantial 9 mm L5/S1 paracentral disc protrusion compressing the thecal sac. B. Axial T2-weighted MRI of the lumbar spine without contrast revealing compression of the right exiting S1 nerve root, consistent with right S1 radiculopathy.

Clinical Insight:

Always correlate MRI findings with the patient’s clinical presentation. For instance, far lateral disc herniations can be easily overlooked if not specifically sought. MRI, being a triplanar modality, requires careful review of axial, sagittal, and coronal sequences. Sagittal views are particularly useful for identifying far lateral disc herniations within the foramina. Coronal sequences help visualize nerve roots and foraminal and extraforaminal regions, crucial areas where far lateral disc herniations often occur.

In cases where there is a discrepancy between clinical findings and imaging results, electrodiagnostic testing becomes invaluable. Electromyography (EMG) and Nerve Conduction Velocity (NCV) studies, along with Somatosensory Evoked Potentials (SSEP), can effectively differentiate radiculopathy from broader peripheral nervous system disorders. It is essential to recognize that while EMG and NCV studies are valuable diagnostic adjuncts when integrated with a comprehensive history, clinical examination, and other diagnostic studies, they are not without limitations and potential pitfalls [5]. Factors that can influence EMG and NCV results include patient cooperation (which can be limited by pain), room temperature, electrolyte and fluid balance, pre-existing medical conditions like diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, or renal failure that can induce peripheral neuropathy, medications such as statins that may cause myopathy, movement disorders causing tremors, previous surgeries like laminectomy (potentially leading to false-positive results in paraspinous muscles), body habitus (extreme obesity hindering needle insertion into muscles), congenital anatomical variations (e.g., Martin-Gruber anastomosis), and the subjective interpretation of data by the clinician [5]. Diagnostic nerve root blocks can also aid in pinpointing the symptomatic level [6].

Treatment Strategies for Lumbar Radiculopathy

Non-Surgical Management

The decision-making process regarding surgical intervention, its timing, and the optimal surgical approaches for lumbar radiculopathy have been extensively researched. However, debates persist. Current guidelines generally advocate for an initial trial of conservative management for lumbar radiculopathy. This includes patient education, encouraging physical activity/exercise, manual therapy techniques (such as McKenzie exercises), and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as first-line treatments [7-9]. McKenzie exercises have demonstrated effectiveness in providing short-term symptomatic relief for patients undergoing conservative treatment for lumbar radiculopathy [10]. Oral corticosteroids, administered as a tapering dose, may also offer benefit during the acute phase [11]. Often, the next step in non-surgical management involves pain-relieving injections. These may include epidural steroid injections, facet joint injections, or transforaminal epidural steroid injections, which have been shown to provide sustained symptom relief [12]. These injections typically combine an anti-inflammatory agent, such as a glucocorticoid, with a long-acting anesthetic like Marcaine. In situations where the source of pain is unclear, spinal injections can serve both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. For example, a patient with significant low back pain and some foot numbness who exhibits extensive spinal arthritis might receive facet joint injections. Profound relief following the injection would suggest that facet joint arthritis, rather than nerve root compression, is the primary pain generator. Conversely, a patient with severe lower extremity pain in an L5 dermatomal pattern experiencing substantial relief after an epidural injection indicates that the compressed left L5 nerve root is likely the pain source, rather than facet joint arthritic changes.

Surgical Intervention

When conservative treatments fail to alleviate symptoms adequately, surgical intervention is considered. The timeframe for determining the failure of conservative measures and considering surgery typically ranges from four to eight weeks [13]. However, identifying ideal surgical candidates versus those who should continue conservative therapy remains a topic of discussion. The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) aimed to address this question [14]. This trial evaluated 501 patients with lumbar disc herniations, comparing surgical and non-surgical treatments. The primary outcome measures were the SF-36 (a health survey) and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores assessed at various intervals. The study concluded that both surgical and non-operative treatment groups showed substantial improvement over two years, with surgery consistently showing slightly greater improvement, although the differences were not statistically significant [14].

A key finding from the SPORT study was that most patients improve over time, regardless of treatment approach. At an eight-year follow-up, patients who benefited most from surgery were those with sequestered disc fragments, symptom duration exceeding six months, higher levels of low back pain, or those who were neither employed nor disabled at the start of the study [4].

Ultimately, the decision on surgical timing often depends on the severity of the patient’s symptoms and clinical judgment. Overall, surgery has been shown to be beneficial for patients with more severe symptoms [15].

Surgical Techniques for Radiculopathy

Discectomy remains the gold standard surgical procedure for lumbar disc herniation. Semmes first described a subtotal laminectomy with dural sac retraction to remove herniated discs in 1939 [16]. Since then, numerous refinements focusing on less invasive techniques have been developed. Caspar and Williams reported advancements in the surgical approach using microsurgical techniques in 1977 and 1978 [17]. In 1997, Foley introduced microendoscopic discectomy (MED) [18, 19].

Surgical options now include open laminectomy with discectomy, “mini-open” hemilaminectomy with microdiscectomy, minimally invasive hemilaminectomy with microdiscectomy using tubular retractors, and MED. Studies have indicated that MED is superior to open surgical techniques, resulting in less nerve irritation as measured by intraoperative EMG studies [20], reduced postoperative analgesic requirements during hospitalization, less operative blood loss, and fewer rest days [21, 22]. Less invasive methods may also lead to reduced joint destabilization due to less tissue disruption and lower surgical and hospital costs [22]. However, minimally invasive techniques have limitations, such as a restricted field of vision for the surgeon and challenges in approaching pathology from different angles. The suitability of minimally invasive techniques should be evaluated case-by-case, considering specific patient and pathology characteristics.

In traditional open discectomy, the target level is first identified using fluoroscopy, followed by a midline incision at the disc level. The incision is deepened subperiosteally to expose the lamina of the upper vertebra and the ligamentum flavum over the interspace laterally. Retractors are then placed. A microscope is brought into the operative field, and hemilaminectomy and partial medial facetectomy are performed using a high-speed drill and Kerrison rongeurs. The ligamentum flavum is detached from the lamina and removed, exposing the nerve root crossing over the disc. The nerve root and thecal sac are retracted medially to expose the annulus. A box incision is made in the annulus, and disc material is removed. A nerve hook can be used to probe anterior to the thecal sac to retrieve any herniated fragments. Loose fragments within the disc space are flushed out with irrigation. The advantages of this open approach include enhanced visualization, the ability to use a broader range of instruments, superior visualization, and the flexibility to approach pathology from multiple trajectories, unlike the restricted trajectory of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) approaches.

For a Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS) approach, a paramedian incision, approximately 2 centimeters off the midline, is made. A small stab incision is made in the lumbodorsal fascia, and a K-wire or initial tubular retractor is docked on the facet joint at the disc space level. A muscle-splitting technique is employed using sequential dilators. A microscope is then utilized, or in the case of MED, a rigid endoscope is inserted. The laminar-facet junction is visualized, and laminotomy, medial facetectomy, and microdiscectomy are performed, similar to the open technique.

Clinical Insight:

When employing the MIS approach, it is crucial to direct the trajectory of the tube perpendicular to the disc of interest. An incorrect trajectory can limit visualization and surgical decompression of the nerve root. Always confirm the trajectory using fluoroscopy.

Conclusion

Lumbar radiculopathy remains a common neurological condition evaluated by neurosurgeons. While the underlying pathology persists, advancements in spine surgery are continually leading to the development of less invasive surgical techniques for patient treatment. A thorough understanding of the signs, symptoms, critical warning signs, radiographic imaging, diagnostic tools, and both conservative and surgical treatment options is essential for effective diagnosis and management. Red-flag symptoms necessitating immediate evaluation include saddle anesthesia, bowel or bladder incontinence, and sudden limb paresis.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always consult with a qualified healthcare professional for diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions.

References

[1] কনডেন ভিসি, হানফোর্ড ডিএ। Lumbar disc disease। ল্যানসেট। 2010 জুন 26;375(9732):2348-58। ডই: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60275-8। পিএমআইডি: 20594568।

[2] র্যাবিন ই, পারফেক্ট জেআর, মিলার জিডব্লিউ, জুনক ডিএল। মার্কিন সামরিক কর্মীদের মধ্যে কটিদেশীয় মেরুদণ্ড এবং স্যাক্রাম রোগের প্রবণতা এবং ঘটনার হার, 2000-2009। স্পাইন জে। 2014 মে 1;14(5):790-800। ডই: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.07.472। ইপাব 2013 আগস্ট 13। পিএমআইডি: 23954430।

[3] স্মিট ইএম, লিনসেন টিএ, ভিল্টজেস জেজে, কোয়েস বিডব্লিউ, ভ্যান টুলডার এমডব্লিউ। কটিদেশীয় ডিস্ক হার্নিশন এর প্রাগনোস্টিক ফ্যাক্টরগুলির একটি পদ্ধতিগত পর্যালোচনা। স্পাইন (ফিলা পিএ 1976)। 2007 ফেব্রুয়ারী 15;32(4):413-23। ডই: 10.1097/01.brs.0000254971.79541.91। পিএমআইডি: 17299298।

[4] টার্টাগলিয়া এমজে, ভেরো-ক্রিস্টোফোরি এ, এলেইন পি, পাস্কোয়াল্ডি এম, ট্রয়েস ডিআই। কটিদেশীয় ডিস্ক হার্নিশন: ইতিহাস, ক্লিনিকাল উপস্থাপনা এবং শারীরিক পরীক্ষা। ইউর রেভার মেড ফার্মাকল বিজ্ঞান। 2010 মে;14(5):441-8। পিএমআইডি: 20545243।

[5] নাদেল জে। ইলেক্ট্রোডায়াগনস্টিক মেডিসিনে ফাঁদ এবং পিটফলস। হাকুম-মেয়ার্স মেড জে। 2017 এপ্রিল;2(1):e1043। পিএমআইডি: 30214915; পিএমসিআইডি: পিএমসি6132252।

[6] বোগডুক এন। ডায়াগনস্টিক মেরুদণ্ড প্রক্রিয়া। 2nd সংস্করণ। এলসেভিয়ার স্বাস্থ্য বিজ্ঞান; 2005। পিএমআইডি: 27148123।

[7] কনস্ট্যান্টিনোভিচ এলএম, লিন্ডবাই-লারসেন পি, কুইস্টগাদ ই, পিটারসেন টি, ক্রিস্টেনসেন এফবি। কটিদেশীয় ডিস্ক হার্নিশন এবং রেডিকুলোপ্যাথি সহ রোগীদের জন্য অ-সার্জিক্যাল চিকিত্সার পদ্ধতিগত পর্যালোচনা। ইউর স্পাইন জে। 2016 ফেব্রুয়ারী;25(2):313-25। ডই: 10.1007/s00586-015-4396-1। ইপাব 2015 ডিসেম্বর 1। পিএমআইডি: 26621063; পিএমসিআইডি: পিএমসি4754359।

[8] ভ্যান ডার গাস্ট আরজে, ওস্টেন্ডোর্ফ আরএ, ভ্রিজ এ, ডেক্কার জে, ভ্যান রুলেন জেএইচ, ভ্যান ওয়েল এমজে, কেম্পার জেবি, ফনকস আরআর। তীব্র কটিদেশীয় রেডিকুলোপ্যাথির জন্য ম্যানুয়াল থেরাপি, ব্যায়াম থেরাপি, বা পরামর্শ: একটি এলোমেলো ট্রায়াল। স্পাইন (ফিলা পিএ 1976)। 2004 জুলাই 15;29(12):1348-56; আলোচনা 1356-7। ডই: 10.1097/01.brs.0000127549.72182.e6। পিএমআইডি: 15213558।

[9] ভ্যান টুলডার এমডব্লিউ, কুইজলার জে, কোয়েস বিডব্লিউ। কটিদেশীয় রেডিকুলার সিন্ড্রোমের জন্য রক্ষণশীল চিকিত্সা। কোচরেন ডেটাবেস সিস্ট রেভ। 2007 অক্টোবর 17;(4):CD001794। ডই: 10.1002/14651858.CD001794.pub2। পিএমআইডি: 17943760।

[10] পিটারসেন টি, সোবর্গ কে, ক্রিস্টেনসেন আর, পিটারসেন পি, লাসলেট এম, নর্ডস্টিন জে, ড্যাম এসই, অ্যান্ডারসেন জে, হ্যান্সেন বিএস, ম্যাকেনজি আর, জুউল-ক্রিস্টেনসেন জে, লিন্ডবাই-লারসেন পি। কটিদেশীয় ডিস্ক হার্নিশনের সাথে রেডিকুলোপ্যাথির জন্য মেকেনজি থেরাপির প্রভাব: একটি এলোমেলো নিয়ন্ত্রিত ট্রায়াল। স্পাইন (ফিলা পিএ 1976)। 2011 ডিসেম্বর 1;36(26):2485-93। ডই: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31821b414b। পিএমআইডি: 21119592।

[11] নোভাক সিবি, ভন ডের লিথ এ, লিন্ডেম্যান্ন ই, মেইনার্স এলসি। কটিদেশীয় রেডিকুলোপ্যাথির জন্য মৌখিক স্টেরয়েড। কোচরেন ডেটাবেস সিস্ট রেভ। 2017 জুন 13;6(6):CD012990। ডই: 10.1002/14651858.CD012990। পিএমআইডি: 28608429; পিএমসিআইডি: পিএমসি6481544।

[12] রাত্তেগাল সিবি, এন্ডারসন আর, ডেইগগার্ড এলডি, পিটারসেন কেডি, ক্রিস্টেনসেন এফবি, মেয়ার এফ, ডাহল বি। দীর্ঘমেয়াদী ফলোআপে কটিদেশীয় রেডিকুলোপ্যাথির জন্য ট্রান্সফোরমাইনাল এপিডিউরাল স্টেরয়েড ইনজেকশন: একটি এলোমেলো নিয়ন্ত্রিত ট্রায়াল। স্পাইন (ফিলা পিএ 1976)। 2015 জুন 15;40(12):847-54। ডই: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000919। পিএমআইডি: 25658842।

[13] ওয়াটসন পি, ফেয়ারব্যাঙ্ক জে, ডেম্পস্টার এম, কুলাস্টি ভি, কনকেলম্যান এফ, ডায়াগনস্টিক এবং ট্রিটমেন্ট পাথওয়ে ওয়ার্কিং গ্রুপ, সোসাইটি ফর ব্যাক পেইন রিসার্চ। কটিদেশীয় রুট পেইন। লুম্বার রুট পেইন ম্যানেজমেন্টের জন্য এসবিপিআর গাইডলাইন। পোস্টগ্রাড মেড জে। 2011 অক্টোবর;87(1032):750-9। ডই: 10.1136/pmj.2010.107498। ইপাব 2011 জুলাই 26। পিএমআইডি: 21795459; পিএমসিআইডি: পিএমসি3193532।

[14] ওয়েইনস্টেইন জেএন, টোস্টেসন টিডি, লুরি জেডি, ট্রুকি জে, লুরিন আরএ, বার্ড জেডি, রবার্টসন ডিআর। কটিদেশীয় ডিস্ক হার্নিশনের জন্য সার্জারি বনাম নন-অপারেটিভ চিকিত্সা: স্পাইন রোগী ফলাফল গবেষণা ট্রায়াল (স্পোর্ট)। জেএএমএ। 2006 নভেম্বর 22;296(20):2441-50। ডই: 10.1001/jama.296.20.2441। পিএমআইডি: 17132830।

[15] ওয়েবার কেএ, হাল্ডেম্যান এস, ডুন ডি, মিলার জে, রুবিনস্টেইন এসএম, ওভারম্যান সি, ফুরমানস্কি ও, রেইটার টি, নরলিয়ান্ড এ, ইয়াজ্দি এম, কাসনার সিটি, গোয়েন জে, ফনকস আরআর, লিন্ডেমুলার ইএইচ, ডেন্নার্ড্ট-স্টাম্পফ এইচবি, গ্রুনিং আর, শোয়েব পি, পেহম্যান এলজে, ভ্যান টুলডার এম। তীব্র এবং দীর্ঘস্থায়ী ননস্পেসিফিক লো ব্যাক পেইন এবং রেডিকুলোপ্যাথির জন্য ইন্টারডিসিপ্লিনারি পুনর্বাসন বনাম বিভিন্ন একক চিকিত্সা হস্তক্ষেপের কার্যকারিতা: একটি পদ্ধতিগত পর্যালোচনা এবং মেটা-বিশ্লেষণ। ইউর স্পাইন জে। 2017 নভেম্বর;26(Suppl 3):513-545। ডই: 10.1007/s00586-017-5230-z। ইপাব 2017 নভেম্বর 2। পিএমআইডি: 29098534; পিএমসিআইডি: পিএমসি5690817।

[16] সেমস আরই। প্রোলাপসড ইন্টারভার্টিব্রাল ডিস্কের অস্ত্রোপচার চিকিত্সা। সাউথ মেড জে। 1939 মে;32(5):525-9। ডই: 10.1097/00007611-193905000-00019। পিএমআইডি: 29114147।

[17] ক্যাসপার ডব্লিউ। কটিদেশীয় ডিস্ক হার্নিশনের মাইক্রোসার্জিক্যাল চিকিত্সা। নিউরো-অর্থোপেডিক্স। 1983;2:63-74। পিএমআইডি: 6879048।

[18] ফোলি কেটি, স্মিথ এমএম, মিশেল বিএস, লেফলার জে। মাইক্রোএন্ডোস্কোপিক ডিসেক্টমি। টেকনিক এবং প্রাথমিক ক্লিনিকাল অভিজ্ঞতা। স্পাইন (ফিলা পিএ 1976)। 1998 সেপ্টেম্বর 15;23(15):1796-802। ডই: 10.1097/00007632-199808010-00023। পিএমআইডি: 9708462।

[19] ফোলি কেটি, মিশেল বিএস। মাইক্রোএন্ডোস্কোপিক ডিসেক্টমি (MED) টেকনিক। নিউরোসার্জারি। 1997 আগস্ট;41(2 সাপ্ল):S197-202। পিএমআইডি: 9258186।

[20] কোমাটসুবারা এম, নাকাইমা এস, ইয়ামাগুচি এইচ, কামিজো আর, ওহটা এস। কটিদেশীয় ডিস্ক হার্নিশনের জন্য মাইক্রোএন্ডোস্কোপিক ডিসেক্টমি এবং মিনি-ওপেন ডিসেক্টমির মধ্যে ইন্ট্রাওপারেটিভ নিউরোফিজিওলজিক্যাল পর্যবেক্ষণ দ্বারা মূল্যায়ন করা স্নায়ু রুটের জ্বালা তুলনা। স্পাইন (ফিলা পিএ 1976)। 2008 নভেম্বর 15;33(24):2631-7। ডই: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181856557। পিএমআইডি: 19001981।

[21] হেসন এমএ, ফোলি কেটি। কটিদেশীয় ডিস্ক হার্নিশনের জন্য মাইক্রোএন্ডোস্কোপিক ডিসেক্টমি। একটি পদ্ধতিগত পর্যালোচনা। জে নিউরোসার্গ ফিমেল। 2000 আগস্ট;11(2):118-23। ডই: 10.3171/foc.2000.11.2.a3। পিএমআইডি: 10913358।

[22] রুইটেনবার্গ বি, ভ্যান রালটে এএফ, হামলুরি আর, ভ্যান ডেন বেন্ডার জে, পেহম্যান এলজে, ভ্যান ডিক সিজি, ভ্রিজ জেপি। কটিদেশীয় ডিস্ক হার্নিশনের জন্য মাইক্রোএন্ডোস্কোপিক ডিসেক্টমি বনাম ওপেন ডিসেক্টমি: একটি এলোমেলো নিয়ন্ত্রিত ট্রায়াল, অর্থনৈতিক মূল্যায়ন এবং ফলো-আপের 2 বছর ফলাফল। স্পাইন (ফিলা পিএ 1976)। 2011 জানুয়ারী 1;36(1):29-39। ডই: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b209fa। পিএমআইডি: 20154582।