Diabetes is a global health crisis, affecting over 415 million individuals worldwide, and projections estimate this number will surge to 642 million by 2040 [1]. In the United States alone, the American Diabetes Association reports that 9.3% of the population, or 29.1 million Americans, are living with diabetes. The complexities of diabetes management in the US are further compounded by the fact that 20% of those with diabetes remain undiagnosed, with 1.4 million new cases emerging each year. Alarmingly, a significant proportion – one-third of adults with diabetes – are not achieving the generally recommended A1C targets for glucose control [2].

The economic burden of diabetes is equally substantial. In 2013, the diagnosed diabetes cost reached approximately $245 billion, marking a 41% increase in just five years. These staggering costs encompass a wide range of expenses, including inpatient care, medications and supplies for managing diabetes and its complications, physician visits, and skilled nursing and long-term care facilities [3].

Primary care settings are pivotal in healthcare delivery, accounting for 52.3% of all medical office visits in the United States in 2013, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes was the fifth most common primary diagnosis in these visits, representing about 3% of primary diagnoses [4]. The core challenge in diabetes care lies in achieving and maintaining optimal long-term glucose control to prevent severe complications such as retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy, while simultaneously minimizing the risk of potentially life-threatening hypoglycemia.

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) technology represents a significant advancement in addressing these challenges, offering the potential to enhance overall glycemic control and reduce hypoglycemic events [5]. Although CGM has been available since the late 1990s, its adoption in primary care has not been widespread. Clinical inertia, encompassing factors such as lack of awareness of its benefits and difficulties in integrating new technologies into existing workflows, often presents a significant hurdle. This article explores the role of CGM in primary care for the early diagnosis and management of type 2 diabetes, addressing barriers to its implementation and emphasizing its value in improving patient outcomes.

The Pivotal Role of Primary Care in Diabetes Diagnosis and Management

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are at the forefront of diabetes diagnosis and management. A 2014 study by the Endocrine Society highlighted a growing disparity between the demand for endocrinologists and their availability, predicting a shortage of 2,700 endocrinologists in the US by 2025 [6]. This increasing demand is largely driven by the aging population, as the prevalence of type 2 diabetes rises significantly with age. A 2012 study using the National Provider Identifier Registry revealed a ratio of endocrinologists to adults aged 65 and older of approximately 6,194 to 1, with average wait times for specialist appointments ranging from 3 to 4 months [7]. Currently, PCPs provide care for approximately 90% of individuals with type 2 diabetes, and this proportion is expected to increase [8]. This underscores the critical role of primary care in the early detection and ongoing management of this prevalent condition.

Given the expanding diabetes population, efficient use of PCPs’ time is crucial for effective patient management. However, diabetes care has become increasingly complex. This complexity arises from the multitude of medication classes available, the need to prevent both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia, the diverse range of medical devices for diabetes management, and the necessity to support patients in making significant lifestyle changes. A study analyzing trends in diabetes care complexity in primary care between 1991 and 2000 found a substantial increase in the number of patients with diabetes taking five or more medications, rising from 18.2% to nearly 30%. Despite this increasing complexity, the proportion of medical visits lasting over 20 minutes only increased by a marginal 3.1% during the same period [9]. This highlights the growing need for tools that can streamline diagnosis and management within the constraints of primary care practice.

How CGM Enhances Diabetes Diagnosis

Traditional methods for monitoring and diagnosing diabetes, such as Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose (SMBG) and A1C testing, have limitations in providing a comprehensive glycemic picture, particularly for early diagnosis. While SMBG is cost-effective and patient-friendly, it only captures glucose levels at single points in time, lacking information on glucose trends. A1C, while providing an average glucose level over three months, fails to reveal daily glucose fluctuations or time spent within the target range. These limitations can hinder the early and accurate diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, where glucose variability and postprandial spikes can be crucial indicators even before fasting hyperglycemia is consistently present.

In contrast, CGM offers dynamic glucose information, including trend data and the percentage of time spent in, above, or below the target glucose range. This detailed glucose profile is invaluable for identifying patterns of dysglycemia that may be missed by traditional methods, facilitating earlier and more accurate Diagnosis Of Type 2 Diabetes In Primary Care settings [10–15].

There are two primary types of CGM systems: Professional CGM (P-CGM) and Real-Time CGM (RT-CGM). P-CGM, also known as “masked” or “retrospective” CGM, involves a short-term monitoring period (6 to 14 days) where the patient wears a sensor but is unaware of the glucose readings in real-time. The data is downloaded and analyzed later by healthcare providers. This method is particularly valuable for diagnostic purposes as it captures a patient’s natural glucose patterns without behavioral modifications that might occur with real-time feedback. This article focuses on P-CGM due to its suitability for diagnostic assessments in type 2 diabetes.

P-CGM’s strength in diagnosis lies in its ability to reveal glycemic patterns influenced by diet, medications, and physical activity, without patient intervention during data collection. This provides healthcare providers with an unbiased view of a patient’s glucose profile, crucial for identifying subtle dysglycemia and confirming a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. The detailed reports generated by P-CGM can then be shared with patients, enhancing their understanding of their condition and motivating them to engage in necessary lifestyle changes and treatment plans [16–18].

Commercially Available CGM Devices for Diagnostic Use

CGM technology relies on a glucose oxidase enzyme within a subcutaneous sensor that converts glucose into hydrogen peroxide, generating a signal proportional to the glucose level. This signal is then translated into glucose readings. Patients typically record meals, medications, and activities, either on paper or using mobile apps, to correlate with the glucose data. Currently, three major manufacturers provide FDA-approved P-CGM devices in the United States: Medtronic, Dexcom, and Abbott. A brief comparison of their systems is provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of P-CGM Systems by Manufacturer (7,8)

| Feature | Medtronic iPro2 P-CGM | Dexcom G4 Platinum | Abbott FreeStyle Libre Pro |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of use (days) | 6 | 7 | 14 |

| Insertion site | Abdomen | Abdomen | Upper arm |

| Number of components | 2 (sensor and recorder) | 3 (transmitter, sensor, and receiver) | 2 (sensor and reader) |

| Minimum number of calibrations per day | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Reading frequency (min) | 5 | 5 | 15 |

| Operational temperature (°F) | 36–86 | 36–77 | 50–86 |

Medtronic

Medtronic’s first P-CGM system, CGMS Gold, was FDA-approved in 1999. The iPro2 system, launched in 2009, uses a 6-day Enlite sensor (FDA-approved in 2016). Data is processed using CareLink software, requiring at least four daily fingerstick calibrations. The sensor is disposable, while the recorder is reusable.

Dexcom

The Dexcom G4 PLATINUM is a practice-owned P-CGM device providing readings every 5 minutes for up to 7 days. It can function as either a real-time or masked CGM system via software configuration, offering flexibility in diagnostic and management settings. It requires at least two calibrations per day.

Abbott

Abbott’s FreeStyle Libre Pro system is unique in requiring no fingerstick calibration. Applied to the upper arm by a healthcare provider, the sensor lasts up to 14 days, simplifying the diagnostic process for both providers and patients.

P-CGM Reports for Enhanced Diagnostic Insights

P-CGM reports are designed to facilitate informed discussions between healthcare providers and patients, providing an evidence-based approach to understanding glucose patterns for diagnosis and management. Manufacturers have focused on creating user-friendly reports suitable for busy primary care settings. These PDF reports, easily stored or printed, typically cover 1 to 14 days of glucose data and include features such as:

- Daily overlay: Superimposes daily glucose traces on a single 24-hour graph, highlighting daily trends and excursions, summarizing high and low glucose events, and showing time-in-range percentages. This is useful for identifying consistent patterns of hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia throughout the day.

- Overlay by meal: Organizes glucose traces by meal and overnight periods based on patient logs, overlaying daily traces for each period to reveal meal-related glucose trends. This is particularly helpful in diagnosing postprandial hyperglycemia.

- Daily summary: Provides a daily breakdown including glucose traces and logged events (meals, medications, activity), offering a comprehensive view of daily glucose control.

- Pattern snapshot report (Medtronic): Summarizes daily glucose data and identifies up to three recurring patterns using algorithms, including general statistics, observed patterns, and potential causes.

- Ambulatory Glucose Profile (AGP; Abbott): A visual chart presenting a complete glycemic overview for up to 14 days, identifying out-of-range glucose levels and trends in hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia.

Key parameters within P-CGM reports include:

- Average Sensor Glucose (SG): The mean glucose value over the monitoring period.

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): Indicates the duration and magnitude of glucose excursions above or below target ranges.

- Percentage High or Low and Time-in-Range: Frequency of hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia and time spent within the desired glucose range.

- Standard Deviation (SD): Measures glucose variability; higher SD indicates greater fluctuations.

- Estimated A1C (eA1C): An A1C estimate derived from average glucose levels, based on the A1C-Derived Average Glucose study [19].

These comprehensive reports empower primary care physicians to gain a deeper understanding of patients’ glucose profiles, aiding in the accurate and timely diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and enabling personalized management strategies.

Recommendations for P-CGM in Early Diabetes Detection

P-CGM is a valuable tool for a wide spectrum of patients, including those at risk for or suspected of having type 2 diabetes [Table 2]. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Diabetes Association recognize the benefits of CGM. While their consensus statements primarily focus on diabetes management, the principles extend to diagnosis. CGM’s ability to detect subtle glycemic excursions and patterns makes it particularly useful in identifying individuals in the early stages of type 2 diabetes, or those with prediabetes who are progressing towards diabetes.

TABLE 2.

Reasons for P-CGM Use in Primary Care

| • Investigation of unexplained hyperglycemia |

|---|

| • Assessment of postprandial glucose excursions |

| • Evaluation of nocturnal glucose patterns |

| • Suspected hypoglycemia unawareness |

| • Monitoring glycemic variability |

| • Guiding lifestyle and dietary modifications for prediabetes and early type 2 diabetes |

| • Optimizing medication regimens in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes |

| • Enhancing patient understanding of glucose responses to food and activity |

| • Increased patient engagement in self-management through visual feedback |

| • Evaluation of the dawn phenomenon in early diabetes |

P-CGM Case Studies Illustrating Diagnostic Utility

Glucose trend data from P-CGM is instrumental in patient consultations, guiding discussions on lifestyle modifications, medication adjustments, and understanding individual glycemic responses. While the following case studies from the Diabetes Assessment and Management Center (DiAMC) in Shreveport, LA, primarily illustrate management benefits, they also highlight the diagnostic power of P-CGM in revealing underlying glycemic disturbances that are crucial for early detection and intervention.

Case 1. Early Detection of Postprandial Hyperglycemia

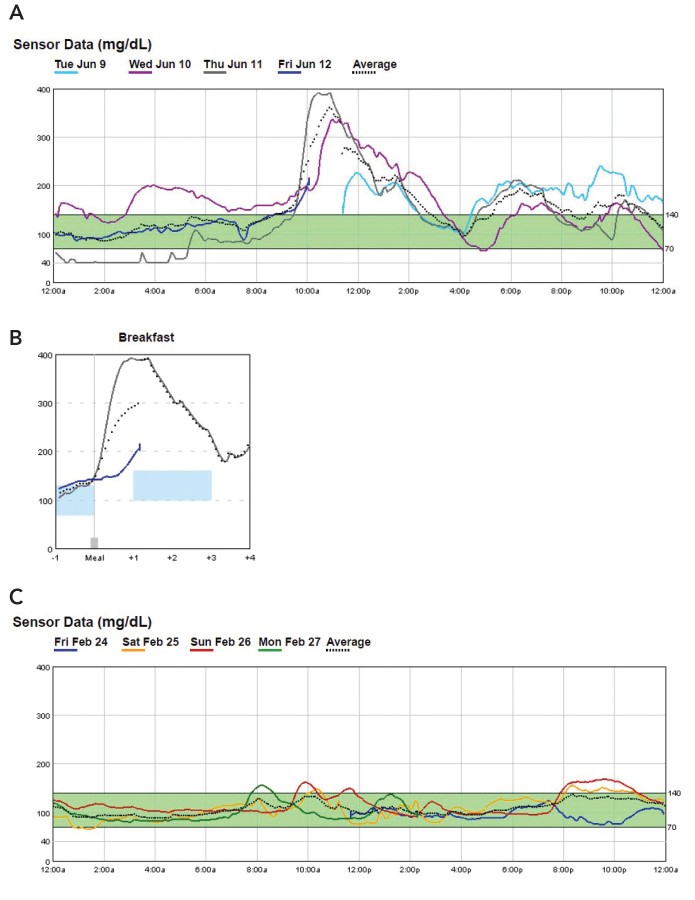

Patient 1, a 64-year-old man, presented with hyperglycemia symptoms and an A1C of 16.1%. A 72-hour P-CGM study quickly identified significant post-breakfast hyperglycemia Figure 1A and B.

FIGURE 1.

Case 1 P-CGM reports: A) initial overlay, B) breakfast overlay, and C) P-CGM overlay ∼18 months after initial evaluation (February 2017).

This targeted diagnostic insight enabled rapid and effective treatment adjustments, leading to significant improvement and diabetes remission. Even in follow-up, P-CGM confirmed sustained glycemic control Figure 1C.

Case 2. Lifestyle Adjustments Guided by CGM Insights

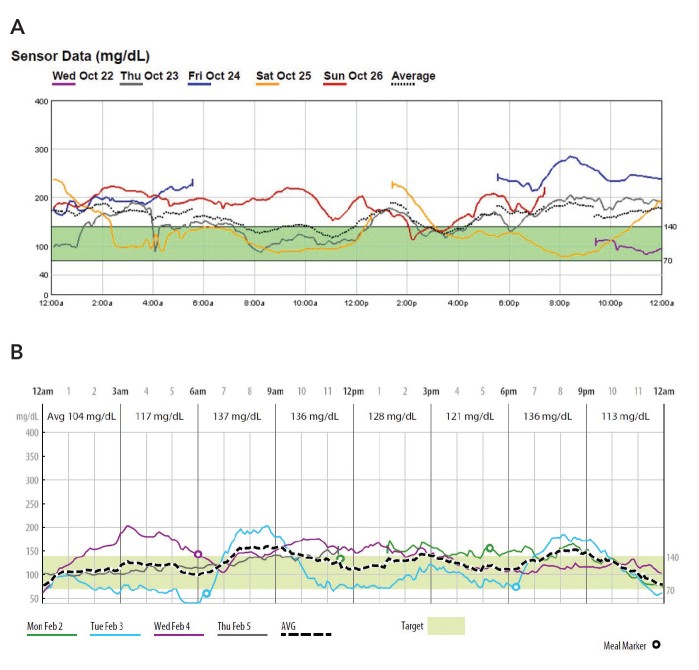

Patient 2, a 46-year-old woman with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes (A1C 13.7%), underwent P-CGM, revealing that her glucose was above 140 mg/dL 60% of the time Figure 2A.

FIGURE 2.

Case 2 P-CGM reports: A) initial P-CGM overlay (October 2014) and B) post-DiAMC program P-CGM overlay (February 2015).

Visualizing her glucose responses to meals and activity through P-CGM empowered her to make effective lifestyle modifications, significantly improving her glycemic control Figure 2B and reducing her A1C to 7.0%. This case demonstrates how CGM aids in patient education and behavior change, critical components of early diabetes management and even prevention in at-risk individuals.

Case 3. Diagnosing and Managing Long-Standing Poorly Controlled Diabetes

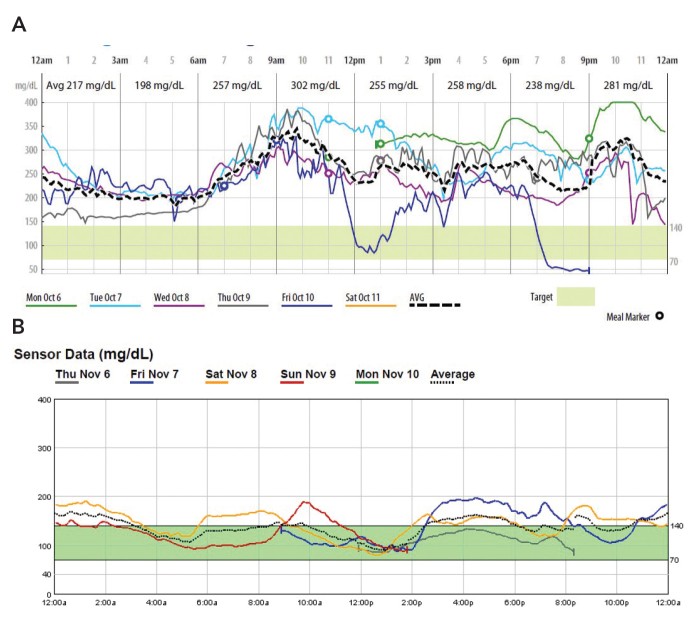

Patient 3, a 54-year-old woman with a 20-year history of type 2 diabetes and A1C of 13.7%, showed extremely poor glycemic control on initial P-CGM, with 96% of readings above target Figure 3A.

FIGURE 3.

Case 3 P-CGM reports: A) initial P-CGM overlay (October 2014) and B) 30-day follow-up P-CGM overlay (November 2014).

P-CGM not only highlighted the severity of her condition but also guided rapid treatment intensification, including lifestyle changes and insulin therapy. Subsequent CGM monitoring demonstrated dramatic improvement in glycemic control Figure 3B, achieving an A1C of 7% within a month.

Case 4. CGM-Assisted Remission of New-Onset Diabetes

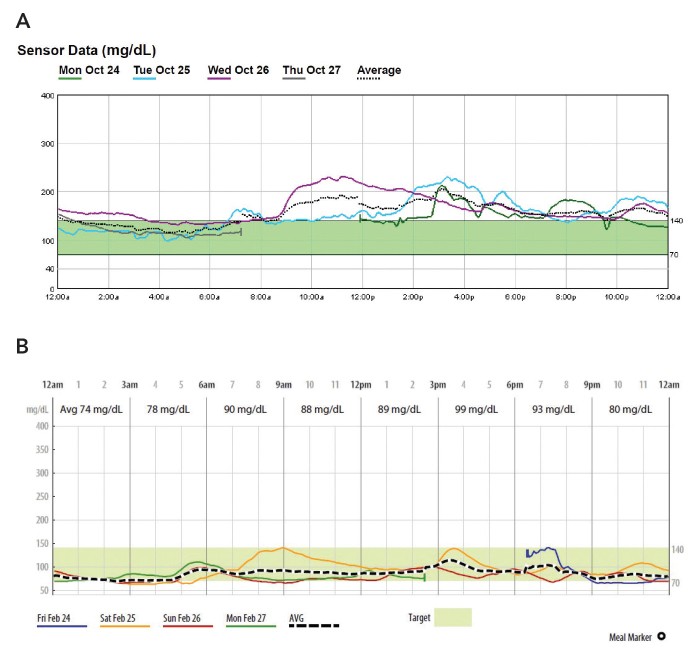

Patient 4, a 75-year-old man newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (A1C 10.5%), exhibited meal-related hyperglycemia on P-CGM Figure 4A.

FIGURE 4.

Case 4 P-CGM reports: A) initial P-CGM overlay (October 2016) and B) recent P-CGM report (February 2017).

P-CGM guided lifestyle interventions and metformin therapy, resulting in diabetes remission. Follow-up CGM confirmed sustained euglycemia Figure 4B and an A1C of 5.9% without medication. This case emphasizes the potential for early intervention, guided by CGM, to reverse the course of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes.

Integrating P-CGM into Primary Care Diagnostic Workflows

Studies like the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial [22] and the T1D Exchange data [23] underscore the link between frequent blood glucose monitoring and improved diabetes outcomes. For early and accurate diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, especially in primary care, P-CGM offers a significant advantage over SMBG alone. Integrating P-CGM into primary care practice is a streamlined process [Table 3]. In the DiAMC program, PCPs introduce P-CGM to patients, explaining its benefits in providing detailed glucose information to guide diagnosis and management. This includes discussing the patient’s role in logging food, activity, and medications during the monitoring period, sensor insertion, and addressing potential questions. Adverse events with P-CGM are rare [24].

TABLE 3.

Two-Visit P-CGM Workflow for PCP Clinic

| Visit 1: P-CGM Initiation | Visit 2: P-CGM Report Review |

|---|---|

| 1. Discuss CGM basics with the patient. | 1. Remove the sensor from the P-CGM recorder and download data. |

| 2. Set up and deploy P-CGM device on patient. | 2. Set preferences for individual target values and generate reports. |

| 3. Describe requirements for calibrating the device using a blood glucose meter. | 3. Interpret reports and provide recommendations to the patient. |

| 4. Reinforce the need for log-keeping (food, medication, and activity) and provide a log sheet or explain how to use a mobile app log (patient’s choice). | 4. Inform the patient about the effects of food, activity, and medications on blood glucose levels. |

| 5. Schedule a return visit to maximize device utility (typically 7–14 days of P-CGM wear, depending on the specific device’s approved duration of use). | 5. Provide the patient with a take-home copy of reports as an educational tool. |

Patients receive detailed instructions, provide consent, and have the sensor inserted during the first visit. They are equipped with a glucose meter for calibration and instructed to wear the sensor for 6-7 days, although even 72-hour data collection is billable and can yield valuable diagnostic information. At the follow-up visit, sensor data is uploaded, logs are reviewed, and P-CGM software generates reports. Healthcare providers analyze these reports to identify trends, understand factors influencing glucose control, and formulate diagnostic and treatment plans. Diabetes educators or other trained staff may assist in data review and patient education, ensuring consistent and efficient P-CGM integration within the primary care setting.

Cost and Reimbursement Considerations for P-CGM

P-CGM devices are typically owned or leased by healthcare providers, with sensors being disposable per-patient items. Reimbursement for P-CGM procedures is available through CPT codes 95250 and 95251 [Table 4].

TABLE 4.

Work Breakdown for CGM CPT Codes

| Code | Workflow | May Be Performed by:* | Face-to-Face Meeting Required? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 95250: CGM placement, training, downloading, and report generation | Sensor insertion | Physician, nurse practitioner, or physician’s assistant or licensed staff within scope of practice or under direct supervision of provider | Yes |

| Patient training | Yes | ||

| Meter instruction | Yes | ||

| Removal of transmitter | Yes | ||

| Downloading of data | No | ||

| Entering blood glucose readings | No | ||

| Generating printed reports | No | ||

| 95251: interpretation of CGM data | Provider analysis of reports | Physician, nurse practitioner, or physician’s assistant | No |

*Staff may provide services if they meet the Medicare “incident to” rules for reimbursement of services rendered incident to a physician’s professional services.

CPT code 95250 covers P-CGM initiation services, including sensor insertion, training, and data downloading, with a national average Medicare reimbursement of $159 when billed by a physician. CPT code 95251 covers data interpretation and analysis, reimbursing approximately $44 on average by Medicare when billed by a physician. Both codes can be billed multiple times per year, and most private payers have P-CGM medical policies, often covering type 1, type 2, and gestational diabetes. Understanding coding and reimbursement is crucial for the sustainable integration of P-CGM into primary care for enhanced diabetes diagnosis and management.

Conclusion: P-CGM – A Vital Tool for Early and Effective Diabetes Care in Primary Settings

Widespread adoption of P-CGM in primary care holds immense potential for improving the early diagnosis and subsequent management of type 2 diabetes. P-CGM technology provides detailed glucose data in an easily interpretable format, empowering PCPs to engage in more meaningful dialogues with patients regarding lifestyle modifications and treatment adjustments. Integrating P-CGM data with information from meal and activity trackers further enhances these conversations, leading to more personalized and effective care plans. As demonstrated in the case studies, intermittent use of P-CGM, alongside lifestyle interventions and medication management, can be a powerful tool for early diagnosis, patient education, and improved diabetes outcomes in the primary care setting.

Duality of Interest

M.S., R.S., J.A.S., and R.V. are employees of Medtronic Diabetes. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions

M.S. wrote the manuscript, researched the data, and contributed to the discussion. W.G. and J.A.S. researched the data, contributed to the discussion, and wrote parts of the manuscript. R.S. and R.V. contributed to the discussion, wrote parts of the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. K.E., C.K., and R.S. contributed to the discussion and wrote parts of the manuscript. M.S. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

[1] International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 7th edn. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2015

[2] American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. J Clin Appl Res Educ 2017;40(Suppl. 1):S1–S135

[3] American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care 2013;36:1033–1046

[4] National Center for Health Statistics. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 summary tables. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2010_namcs_web_tables.pdf. Accessed 12 December 2016

[5] Национальный стандарт Российской Федерации. Системы управления качеством. Основные положения и словарь. Available from http://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200109444. Accessed 12 December 2016

[6] Feldman EL, Tutuncu AN, Hellman R, et al. Endocrine Society 2014 Workforce Report: Endocrine Society Task Force on Endocrine Workforce. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:3277–3284

[7] অপেক্ষা করুন। 2012 National Provider Identifier Registry data. Available from https://npiregistry.cms.hhs.gov/registry/DownloadRegistryDBs. Accessed 12 December 2016

[8] Lin EH, Rutter CM, Peterson D, et al. Intensive diabetes therapy and mortality among patients with chronic kidney disease. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:285–292

[9] Gill JM, Mainous AG 3rd, Nsereko M, et al. Trends in diabetes care complexity in family practice. Ann Fam Med 2005;3:508–512

[10] Bergenstal RM, Tamborlane WV, Ahmann A, et al. Effectiveness of sensor-augmented insulin pump therapy in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2010;363:311–320

[11] Deiss D, Bolinder J, Riveline JP, et al. Real-time continuous glucose monitoring in patients with type 1 diabetes and impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia or severe hypoglycaemia treated with multiple daily insulin injections (SENSOR trial): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:391–400

[12] Національна академія медичних наук України. Інститут ендокринології та обміну речовин ім. В.П. Комісаренка. Available from http://www.endocrin.kiev.ua/. Accessed 12 December 2016

[13] Національна академія медичних наук України. Інститут ендокринології та обміну речовин ім. В.П. Комісаренка. Available from http://www.endocrin.kiev.ua/. Accessed 12 December 2016

[14] Vigersky RA, Fonda SJ, Chellappa M, et al. Real-time continuous glucose monitoring for patients with type 2 diabetes on basal insulin. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2011;5:977–984

[15] Vigersky RA, McMahon C. The science of intermittent scanning continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Technol Ther 2019;21(Suppl. 2):S2-S15

[16] Miller KM, Beck RW, Bergenstal RM, et al. Evidence of adherence and effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013;36:2009–2014

[17] Sequeira PA, Roy TA, Arora P, et al. Impact of real-time continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes using basal insulin. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2013;7:146–155

[18] Soupal J, Petruzelkova L, Cigna M, et al. Intermittent scanning continuous glucose monitoring system and its impact on glycemic variability in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016;18:178–183

[19] Nathan DM, Kuenen J, Borg R, et al. Translating the A1C assay into estimated average glucose values. Diabetes Care 2008;31:1473–1478

[20] Grunberger G, Sherr JL, Allende-Vigo MZ, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring in adults with diabetes. Endocr Pract 2016;22:1383–1421

[21] American Diabetes Association. Glycemic targets. Sec. 6. In Standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. J Clin Appl Res Educ 2017;40(Suppl. 1):S48–S56

[22] Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993;329:977–986

[23] T1D Exchange Clinic Network. T1D Exchange clinic registry. Available from https://www.t1dexchange.org/research/registry. Accessed 12 December 2016

[24] Brazg RL, Brazg TV, Chase HP, et al. Clinical experience with a professional continuous glucose monitoring system in outpatient diabetes management. Endocr Pract 2007;13:497–504

[25] Medical Policy & Technology Assessment Committee. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). Available from https://www.bluecrossnc.com/sites/default/files/content/dam/corporate/public/pdfs/medicalpolicy/continuous_glucose_monitoring.pdf. Accessed 12 December 2016