Understanding and Addressing Spelling Disorders in Youth

Reading and spelling disorders affect a significant portion of children and adolescents, ranging from 3% to 11%. These difficulties in written language skills can severely impact academic performance and are frequently observed alongside other mental health conditions. Despite the prevalence and impact, considerable ambiguity remains regarding the most effective methods for both diagnosis and treatment. This article addresses these critical issues by presenting evidence-based guidelines derived from a comprehensive systematic review of existing literature and expert consensus.

Methods of Systematic Review and Guideline Development

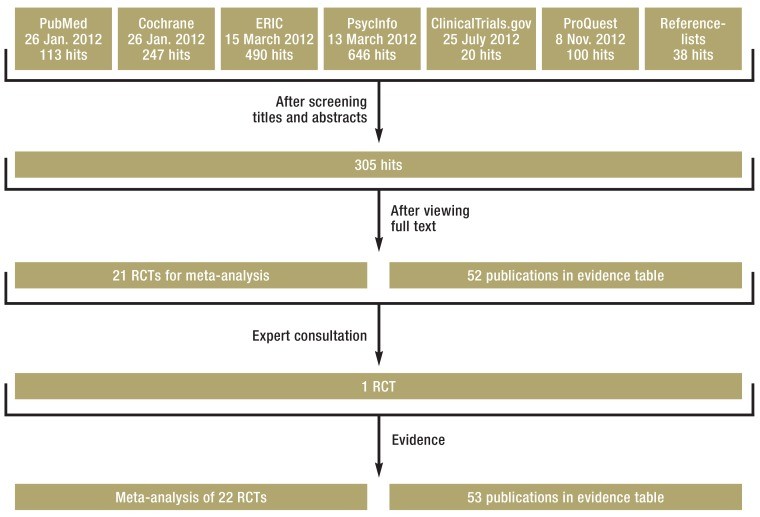

To establish robust recommendations, a thorough search was conducted across multiple databases and reference lists to identify relevant publications. The gathered evidence was meticulously summarized and, where feasible, analyzed using meta-analysis techniques. The culmination of this rigorous process was a consensus conference where the developed recommendations were finalized.

Key Findings: Diagnostic Criteria and Effective Interventions

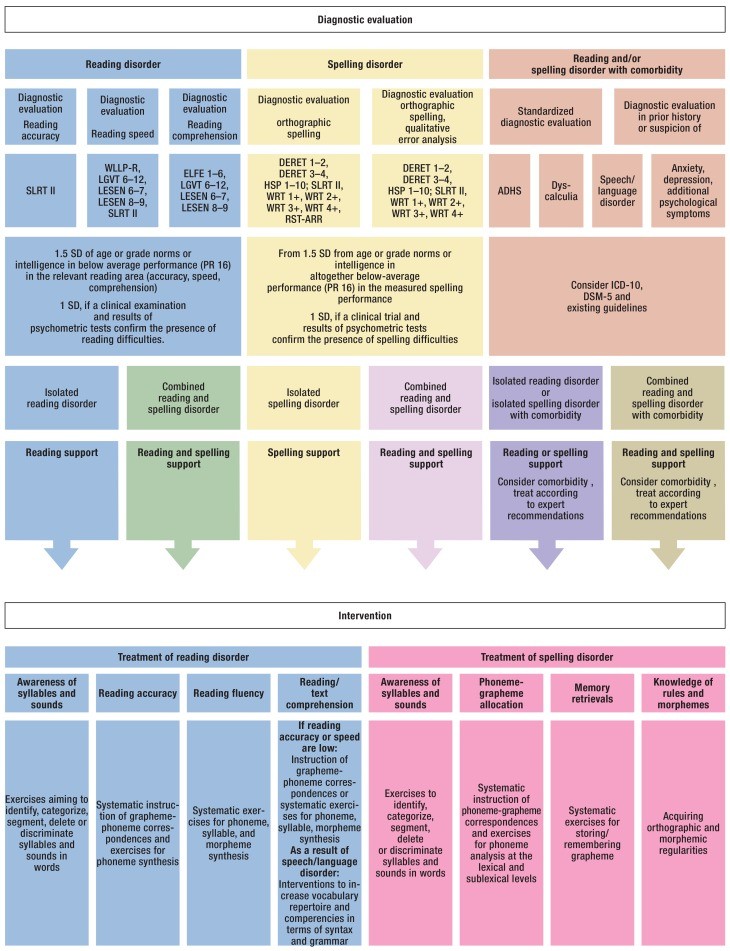

The consensus reached underscores that a diagnosis of reading and/or spelling disorder should only be made when an individual’s performance in these areas falls demonstrably below the average expectation for their age and educational level. Furthermore, a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation should include an assessment for co-occurring conditions such as attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety disorders, or difficulties in arithmetic.

Regarding intervention strategies, systematic instruction focusing on the fundamental connections between letters and sounds, along with the analysis and synthesis of letter-syllable-morpheme units, is strongly recommended to enhance both reading and spelling skills (recommendation grade A). Meta-analysis supports this, indicating a significant positive effect (g’ = 0.32). Specifically for improving Diagnosis Spelling accuracy, training in spelling rules has been identified as the most effective approach (recommendation grade A). Conversely, certain interventions such as Irlen lenses, visual or auditory perceptual training, hemispheric stimulation, piracetam, and prism spectacles are not supported by evidence and are not recommended (recommendation grade A).

Conclusions: Evidence-Based Practices for Diagnosis Spelling and Treatment

This evidence- and consensus-based guideline represents a significant advancement by providing clear directions for the diagnosis spelling and treatment of reading and/or spelling disorders in children and adolescents. The emphasis is placed on systematic and thorough interventions targeting reading and spelling abilities, coupled with the appropriate management of any comorbid disorders. It is crucial to recognize that the effectiveness of many currently used treatments remains unverified. Future practices should prioritize evidence-based methods and rigorously evaluate new treatments through randomized, controlled trials. Notably, the article points out a significant gap in available diagnostic tools and therapeutic methods tailored for adults with these disorders, highlighting an area for future development.

Worldwide, a substantial percentage of school-aged children and adolescents struggle with reading and/or spelling disorders, with prevalence rates ranging from 3% to 11% [1–3]. International classifications like the ICD-10 recognize both combined reading and spelling disorder (affecting approximately 8% of the population) and isolated spelling disorder (around 7%). Isolated reading disorder, though not formally included in ICD-10, is also prevalent, affecting about 6% [1]. Reading disorder manifests as frequent errors in silent and oral reading, slow reading speed, and impaired reading comprehension. These challenges impact performance across all academic subjects, including understanding mathematical problems and learning foreign languages [4]. Spelling disorder becomes apparent early in the writing process, characterized by significant difficulties in grasping sound-letter relationships and accurately spelling words and word parts [5]. Combined disorders present with symptoms of both reading and spelling difficulties.

Children experiencing reading and spelling disorders are often seen in primary care settings, such as pediatric offices or public health services, presenting with psychosomatic symptoms like headaches, stomachaches, nausea, and a lack of motivation. Repeated academic failures can lead to severe fear of failure and a negative self-perception of their abilities. Consequently, comorbidity with both externalizing and internalizing disorders is high [6]. Approximately 20% of children with reading disorders develop anxiety disorders, and conditions like depression and conduct disorders are also frequently observed [7–10]. Without appropriate intervention and support, reading and spelling disorders can lead to school failure, absenteeism, and have serious long-term consequences for educational and professional attainment, as well as psychological well-being in adulthood [11–13].

The diagnosis spelling disorder, along with reading disorders, has historically suffered from inconsistencies in medical and psychological practice. This variability stems from differing methodological approaches, diagnostic criteria, and assessment tools. Similarly, the treatment landscape is broad, offering a wide array of methods, many of which lack adequate or any scientific evaluation [15]. This situation underscores the urgent need to evaluate the effectiveness of support methods and the reliability and validity of diagnostic approaches to establish clear, evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice.

To address this need, the German Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy (DGKJP) spearheaded the development of an evidence-based and consensus-based (S3) clinical practice guideline for the diagnostic evaluation and treatment of reading and spelling disorders in children and adolescents.

Methodological Approach to Guideline Development

The recommendations put forth in this guideline are based on comprehensive, systematic literature searches across several prominent databases (PubMed, PsycInfo, ERIC, Cochrane, ClinicalTrials.gov, ProQuest) (Figure 1). Where possible, the data extracted from these searches were subjected to meta-analysis. The literature search encompassed publications up to April 2015. To ensure comprehensiveness, databases such as PSYNDEX and Testzentrale were also consulted. Two independent assessors evaluated each identified publication against predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (see eBox 1 for inclusion criteria). Studies meeting the inclusion criteria were then rigorously evaluated for methodological quality using checklists from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and assigned evidence levels based on the Oxford Center for Evidence Based Medicine (OCEBM) scheme [16].

Key Diagnostic and Intervention Messages

- Diagnosis spelling and reading disorder should be grounded in a demonstrable discrepancy between an individual’s reading and/or spelling proficiency and age-related norms, grade-level expectations, or intellectual capacity (IQ). Specifically, a diagnosis is warranted only when reading and/or spelling performance deviates from age or grade norms by at least one standard deviation.

- A thorough diagnostic process must include screening for associated conditions, such as attention deficit syndrome (ADS), attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety disorders, or arithmetic skill disorders.

- Interventions should be designed to directly address the symptoms of reading and spelling disorders while also considering and managing any co-occurring conditions.

- Supportive measures should be initiated as early as possible, ideally in a child’s first year of formal schooling, for those identified as having difficulties in acquiring reading and spelling skills.

- Intervention should be sustained until the individual achieves a level of reading and spelling proficiency that enables full and age-appropriate participation in social and public life.

To assess the methodological rigor of psychometric tests used for evaluating reading and spelling abilities, an abbreviated version of the DIN 33430 Screen V2 checklist 1 [17] was used. Manuals for these tests were evaluated based on core quality criteria [18 deemed essential for diagnostic testing methods (see eBox 2). A consensus meeting, facilitated by a neutral moderator, involved structured voting by participating specialty societies (eBox 3) on each recommendation. A consensus level was defined as strong if agreement exceeded 95%, consensus for 75–95% agreement, and majority agreement for 50–57%.

Diagnostic Evaluation of Spelling Skills

Clinical practice employs three primary diagnostic criteria for diagnosis spelling and reading disorders, rooted in the ICD-10 [19, each potentially yielding different prevalence rates: age discrepancy, grade discrepancy, and IQ discrepancy criteria. A key challenge is determining the most appropriate criterion or combination of criteria for future diagnostic use. Given the absence of empirical evidence differentiating therapeutic effects, disorder progression, or heritability based on whether diagnosis is based on age/grade or IQ discrepancy (evidence table available at www.kjp.med.uni-muenchen.de/forschung/leitl_lrs.php for diagnostic evaluation), no single criterion is preferentially recommended. Instead, any one of these three criteria can serve as a basis for diagnosis. When using the IQ discrepancy criterion, it’s essential to confirm below-average reading and spelling achievements. Specifically, the deviation from age or grade norms should be at least one standard deviation (SD) (Table 1). Regarding psychometric tests, no comparative criteria were available to rank instruments definitively. However, the guideline provides recommendations on preferred testing methods for assessing reading and/or spelling ability (eTable 1).

Recommended Diagnostic Criteria for Spelling Assessment

| Diagnostic criterion | Observed as | Expressed as |

|---|---|---|

| Age discrepancy criterion | Below average performance in the chosen testing method compared with age standard | At least percentile rank≤ 16 or T value ≤ 40 |

| Grade discrepancy criterion | Below average performance in the chosen testing method compared with standard grade performance; if available, use of school-type specific standard | At least percentile rank≤ 16 or T value ≤ 40 |

| Age or grade standard and intelligence discrepancy criterion | Below average performance in the chosen testing method compared with standard age or grade performanceANDUnexpected poor performance in the chosen testing method compared with IQ | At least percentile rank ≤ 16 or T value ≤ 40ANDDiscrepancy from respective T or IQ values ≥ 1 standard deviation |

Beyond diagnostic instruments, a comprehensive evaluation should include a detailed history of development, family, and school experiences, alongside neurological and physical examinations, intelligence testing, and differential diagnostic assessments to rule out visual or auditory processing disorders [20.

Differential Diagnosis: Ruling Out Other Conditions

In cases where children or adolescents report symptoms such as blurred vision, rapid fatigue, and headaches after extended reading, particularly if symptoms worsen throughout the school day, an eye-related reading disorder should be considered. These disorders can arise from several causes:

- Refractive errors (anomalies in how the eye focuses light), especially hyperopia (farsightedness)

- Latent and intermittent strabismus (heterophoria, eye misalignment)

- Hypo-accommodation (reduced ability to focus on near objects)

- Convergence insufficiency (difficulty in coordinating eye movement to focus on close objects).

Hypo-accommodation and convergence insufficiency often co-occur [21. eTable 2. summarizes the recommended diagnostic approach for ophthalmological assessment. Studies indicate that approximately 6.7% of primary school children diagnosed with reading and spelling disorders may have underlying ocular issues contributing to their reading difficulties [22].

Peripheral hearing problems are another critical differential diagnosis, as they can significantly impair language acquisition and the development of writing skills. Hearing problems are categorized into conductive hearing loss, sensorineural hearing loss, and combined hypoacusis [23]. The guideline recommends the following methods for diagnosing hearing problems in school-aged children:

- Impedance audiometry with stapedius reflex measurement to evaluate middle ear ventilation.

- Otoacoustic emissions to assess the function of auditory hair cells.

- Hearing threshold level determination using air and bone conduction audiometry.

A hearing disorder is considered relevant to speech development if bilateral hearing loss (>25 dB in the better ear) has persisted for more than three months or is permanent within the primary speech frequency range (500 to 4000 Hz). Even mild hearing loss can significantly impair a child’s ability to discriminate sounds, a foundational skill for acquiring spelling and written language proficiency.

Effective Support Strategies for Spelling Improvement

The guideline focuses on evaluating the effectiveness of various therapeutic options for treating reading and spelling disorders. These options range from symptom-specific approaches that directly target reading and spelling deficits and their prerequisite skills, to causal therapies aimed at improving basic functions like auditory and visual perception. Medication treatments and various esoteric or alternative medical approaches also exist.

Meta-analysis has demonstrated that only symptom-specific interventions show improvement in reading and spelling performance. Consequently, these approaches are recommended for treating these disorders. Table 2 presents the included studies and meta-analysis results.

Meta-Analysis of Intervention Methods

| Intervention method | Effect sizes | References |

|---|---|---|

| Phonological awareness training | Reading performance: g’ = 0.28; 95% CI [–0.24; 0.80] | (e33, e34) |

| Training in letter-syllable -morpheme synthesis and analyses of phonemes, syllables and morphemes | Reading performance: g’ = 0.32; 95% CI [0.18; 0.47] Spelling performance: g’ = 0.34; 95% CI [0.06; 0.61] | (e34– e45) |

| Whole word reading training | Reading performance: g’ = 0.30; 95% CI [–0.11; 0.71] | (e35, e39, e41, e45) |

| Reading comprehension training | Reading performance: g’ = 0.18; 95% CI [–0.18; 0.54] | (e37, e46) |

| Auditory perception training | Reading performance: g’ = 0.39; 95% CI [–0.07; 0.84] | (e47, e48) |

| Medication treatment | Reading performance: g’ = 0.13; 95% CI [–0.07; 0.32] | (e49, e50) |

| Irlen lenses | Reading performance: g’ = 0.316; 95% CI [–0.01; 0.64] | (e51, e53) |

Systematic instruction in letter-sound correspondences and letter-syllable-morpheme synthesis is most effective in developing reading performance (g’ = 0.32; 95% confidence interval [0.18; 0.47]) [24]. For diagnosis spelling improvement, systematic instruction in sound-letter correspondences, sound-syllable-morpheme analysis (g’ = 0.34; [0.06; 0.61]), and training to acquire and generalize orthographic rules are most beneficial [24–27]. Figure 2 provides examples of evidence-based methods. Additionally, reading performance can be enhanced by using larger print (≥ 14 pt) and increased spacing between letters, words, and lines (≥ 2.5 pt) in reading materials [28].

The meta-analysis did not confirm the effectiveness of auditory or visual perception and processing training programs (g’ = 0.39; [–0,07; 0.84]) [e1–e3], medication (g’ = 0.13; [–0.07; 0.32]), and Irlen lenses (g’ = 0.316; [–0.01; 0.64]) [e1–e3] [24]. Controlled studies have also failed to demonstrate benefits from neuropsychological hemisphere-specific stimulation training compared to no treatment [e4–e6]. Alternative approaches such as homeopathy, acupressure, osteopathy, kinesiology, food supplements, visual biofeedback, motor exercises, and occlusion therapy (eTable 3) have not been shown to improve reading and spelling performance in affected children [e7–e11].

Prism spectacles have not been proven effective for improving spelling performance. While prisms are used for heterophoria, this condition does not explain the symptoms of reading and spelling disorders. The concept of visual angle defects, arising from the H J Haase measurement and correction methodology, should be distinguished from heterophoria. Prisms are used to correct fixation disparity, but the H J Haase methodology for determining fixation disparity is scientifically controversial and not widely accepted [e12, e13].

Optimal Support Settings and Duration

The guideline provides recommendations regarding the initiation and duration of treatment, therapist qualifications, and the most effective support settings (individual or small group).

Early intervention is crucial; support should begin in the first year of schooling as it is more effective than starting later (recommendation grade A) [29].

Support measures are recommended in individual or small group settings (≤ five individuals) (recommendation grade A). Effectiveness does not significantly differ between individual and group sessions [24]. However, the choice of setting should consider comorbidities and the severity of the disorder.

The therapist’s profession influences intervention effectiveness. Interventions led by teachers and study authors showed significant effectiveness. However, interventions by peers, parents, or university students did not consistently demonstrate effectiveness [24, 30]. Therefore, interventions should be implemented by experts in reading and spelling development and intervention (recommendation grade A).

Longer intervention duration is associated with greater improvement in reading and/or spelling performance [24, 31]. Support should continue until the individual achieves age-appropriate reading and spelling skills for full participation in public life (clinical consensus point). This often requires several years of intensive support, which is frequently limited by healthcare funding structures. Consequently, individuals with reading and spelling disorders may face diminished scholastic and psychosocial integration prospects compared to their peers.

Addressing Comorbidities in Diagnosis and Treatment

The impact of comorbidities on the effectiveness of treatments for reading and spelling disorders has been historically underestimated. Common comorbidities include anxiety disorders, depressive symptoms, hyperkinetic disorder or ADHD, school absenteeism, and conduct disorders in adolescents. ADHD is four times more prevalent in children and adolescents with reading and spelling disorders, with prevalence rates of 8–18% in diagnosed cases [7, 9, 32].

Furthermore, significantly increased rates of anxiety disorders (20%) and depressive disorders (14.5%) are found in young individuals with reading and spelling disorders. The risk of anxiety disorder is quadrupled, and social phobia risk may increase sixfold [7, 9, 10].

Comorbidity between reading and spelling disorders and arithmetic skill disorders is also substantially elevated, with prevalence rates between 20% and 40% in children diagnosed with reading and spelling disorders. The risk of arithmetic skill disorders is increased four to fivefold [33]. Prevalence of both disorders in the general population is 3–8% [33–37].

Studies on language performance in children with reading and spelling disorders show a significant accumulation of expressive and/or receptive language disorders, although reliable prevalence rates are not yet available [38, 39].

In summary, the diagnosis spelling and reading disorders should include a thorough assessment of comorbidities, which should then be integrated into the treatment plan.

Future Directions: Action and Research Needs

Significant needs for action and further research remain in both the diagnosis spelling and treatment of reading and spelling disorders.

Many diagnostic procedures were excluded from guideline recommendations due to insufficient methodological quality. Reliable and valid tools for early detection of precursor skills for reading and spelling disorders are lacking. Germany lacks standardized spelling tests applicable throughout the entire school year; many existing tests are limited to specific time intervals. Furthermore, reading tests for adolescents and adults are absent in Germany, making diagnosis in these age groups exceedingly difficult.

In treatment, substantial research is needed, particularly randomized controlled trials, for all interventional approaches and methods [40].

Prevalence studies on comorbidities in reading and spelling disorders are scarce in German-speaking regions. High-quality studies in this area are primarily available for arithmetic skill disorders [1, 33]. Regional factors are critical for generalizing research findings due to variations in diagnostic approaches, criteria, and environmental conditions. Prevalence estimates for developmental scholastic skill disorders should be based on unselected samples to avoid biases.

Implementing the S3 Guideline in Practice

This guideline is intended for use in all clinical, outpatient, and inpatient settings where children and adolescents with school-related problems and associated psychosomatic symptoms or psychological disorders are seen. It also provides valuable guidance for diagnostic evaluation in eye care centers, ENT practices, and pediatric audiology for children with hearing, reading, and spelling problems. Currently, statutory health insurers do not cover targeted support interventions for reading and spelling disorders, placing the financial burden of treatment on affected individuals. The variety of available support methods is vast and often confusing, with unclear effectiveness. Methods lacking evidence of effectiveness should be avoided. These guidelines offer clear, evidence-based therapeutic recommendations that can help reduce costs and prevent serious psychosocial stress resulting from ineffective or inadequate therapy.

References

1. Landerl K, Ramus F, Moll K, Lyytinen H, Leppänen PH, Lohvansuu K, et al. Predictors of developmental dyslexia in European orthographies with varying complexity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(6):686–94. DOI: 10.1111/jcpp.12026

2. Brunswick N, McManus IC, Steer C, Wood D. Literacy, numeracy, and adult social inclusion. London: Department for Education and Skills; 2007.

3. Carroll JM, Maughan B, Goodman R, Meltzer H. Literacy difficulties and psychiatric disorders: evidence for comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(5):524–32. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00381.x

4. Warnke A, Henninghausen J. Leitlinie zur Diagnostik und Behandlung der Lese- und/oder Rechtschreibstörung. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2007;35(3):159–80. DOI: 10.1024/1422-4917.35.3.159

5. Dummer-Smoch L. Grundlagen der Lesen- und Rechtschreibschwierigkeiten. 6., vollst. überarb. Aufl. edn. München: Ernst Reinhardt; 2014.

6. DuPaul GJ, Gormley MJ, Laracy SD. Comorbidity of ADHD and reading disorders: implications for diagnosis and intervention. J Learn Disabil. 2013;46(1):30–43. DOI: 10.1177/0022219412464351

7. Willcutt EG, Pennington BF, Olson RK, DeFries JC. Comorbidity of reading disability and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: differences by gender and subtype. J Learn Disabil. 2000;33(2):179–91. DOI: 10.1177/002221940003300205

8. Zentall SS, Goldstein S. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: theoretical models and implications for diagnosis, treatment, and research. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1999;11(3):207–19. DOI: 10.1080/095402699100171

9. August GJ, Garfinkel BD. Comorbidity of ADHD and reading disability among clinic-referred children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1993;21(1):29–45. DOI: 10.1007/BF00913753

10. McGee R, Share DL, Moffitt TE, Williams S, Silva PA. Reading disability, behavior problems, and juvenile delinquency. Criminology. 1988;26(4):589–609. DOI: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1988.tb00853.x

11. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Literacy at age 12 and educational achievement at ages 15 and 18 years. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1995;36(3):461–75. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb02300.x

12. Maughan B, Pickles A, Hagell A, Rutter M, Yule W. Reading problems and antisocial behaviour: developmental trends in comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1996;37(4):405–18. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01419.x

13. Snowling MJ, Melby-Lervåg M, Hulme C. Evidence for, and assessment of, cognitive deficits in dyslexia. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(2):119–28. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02284.x

14. национальные клинические рекомендации. расстройства обучения: дислексия, дизграфия, дискалькулия. Союз педиатров России. 2016.

15. Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA. Dyslexia (specific reading disability). Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1301–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.09.059

16. OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. 2011.

17. DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e. Normen-Download der DIN 33430 Screen V2. Berlin: Beuth Verlag GmbH; 2013.

18. Moosbrugger H, Kelava A. Testtheorie und Fragebogenkonstruktion. 2. Aufl. edn. Heidelberg: Springer; 2012.

19. Dilling H, Mombour W, Schmidt MH, Schulte-Markwort E. Internationale Klassifikation psychischer Störungen ICD-10 Kapitel V (F). Klinisch-diagnostische Leitlinien. 5. Aufl. edn. Bern: Huber; 2000.

20. Birle K, Weber J, Schulte-Körne G. [Vision and reading disability]. Ophthalmologe. 2010;107(12):1149–55. DOI: 10.1007/s00347-010-2251-8

21. von Kienlin M, Mühlendyck H. Orthoptics. 4th revised edition. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2015.

22. Richard P, Auffarth GU, Golenhofen M, Kohnen T, Kreiner CF, Langenbucher A, et al. [S2k guideline: Refractive errors and strabismus in children]. Strabismus. 2010;18(4):121–40. DOI: 10.3109/09273972.2010.533255

23. Biesalski HK, Grimm P, editors. Taschenatlas der Ernährung. 5., vollst. überarb. Aufl. edn. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2011.

24. Schneider W, Niklas F, Ehm JA. Entwicklung von Vorläuferfertigkeiten und des Lesens und Rechtschreibens im Vorschul- und frühen Schulalter. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2016.

25. Stock C, Marx P, Schneider W. Training der phonologischen Bewusstheit, der Buchstabenkenntnis und der Automatisierung des Lesens und der Rechtschreibung. Kindheit und Entwicklung. 2010;19(3):162–70. DOI: 10.1026/0942-5403/a000017

26. Naumann CL, Prediger S, Schneider W. Wirksamkeit eines computerbasierten Trainings zur Förderung von Rechtschreibstrategien. Empirische Sonderpädagogik. 2012;4(3):249–68.

27. Schulte-Körne G, Mathwig F, Mannhaupt G, Hasselhorn M. Prävention von Leseschwierigkeiten durch Förderung der phonologischen Bewusstheit im Kindergarten. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2004;32(2):103–10. DOI: 10.1024/1422-4917.32.2.103

28. Schnitzer C, Richter T, Faupel D, Gross C, Huber S, Löffler C, et al. Wirksamkeit von Maßnahmen zur Verbesserung der Leseflüssigkeit bei Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Lesestörung. Empirische Sonderpädagogik. 2014;6(1):5–22.

29. Torgesen JK, Mathes PG, Simmons D. Individual variation in response to early interventions for phonological awareness and reading. J Educ Psychol. 1997;89(4):667–82. DOI: 10.1037/0022-0663.89.4.667

30. Galuschka K, Görgen R, Brunner R, Mayer A, Schulte-Körne G. Effectiveness of spelling intervention for students with orthographic difficulties: a meta-analysis. Learn Disabil Res Rev. 2014;29(4):177–89. DOI: 10.1111/ldrr.12077

31. Vellutino FR, Scanlon DM, Small SG, Tanzman MS. Longitudinal research on reading disability in children: assumptions, findings, and future directions. Learn Disabil Res Pract. 1991;6(1):58–63.

32. German guideline (S3) “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents”. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2016;44(2):157–71. DOI: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000423

33. Moll K, Kunze S, Neuhoff N, Bruder J, Schulte-Körne G. Comorbidity of specific learning disorders: prevalence and predictive factors. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132883. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132883

34. Landerl K, Moll K, Ramus F. A meta-analysis of phonological awareness, visual-orthographic and lexical retrieval deficits in dyslexia. Sci Stud Read. 2014;18(2):97–124. DOI: 10.1080/10888438.2013.856387

35. Dirks E, Spyer G, van Lieshout EC, de Sonneville LM. Prevalence of combined reading and arithmetic disabilities. J Learn Disabil. 2008;41(2):183–91. DOI: 10.1177/0022219407313799

36. Shalev RS, Auerbach J, Manor O, Gross-Tsur V. Developmental dyscalculia: prevalence and prognosis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;9 Suppl 2:II58-64.

37. Swanson HL, Jerman O. Math disabilities: a selective meta-analysis of the literature. Rev Educ Res. 2006;76(2):249–74. DOI: 10.3102/00346543076002249

38. Catts HW, Adlof SM, Weismer SE. Language deficits in poor readers: a meta-analysis of reading comprehension measures. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2006;49(2):278–96. DOI: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/023)

39. Scarborough HS. Very early language deficits in dyslexic children. Child Dev. 1990;61(6):1728–43. DOI: 10.2307/1130953

40. Leitlinienreport. Evidenzbasierte Leitlinien – S3-Leitlinie: Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit- / Hyperaktivitätsstörung im Kindes-, Jugend- und Erwachsenenalter. AWMF-Register Nr. 028–048. 2018.