Introduction to Dyspnea

Breathlessness, clinically termed dyspnea, is a prevalent symptom affecting a significant portion of ambulatory patients, up to 25%. This distressing sensation of difficult or labored breathing can stem from a myriad of underlying medical conditions, some of which pose immediate threats to life. Prompt and accurate diagnosis is therefore paramount in managing dyspnea effectively. The diagnostic process can be complex, especially when considering the subjective nature of dyspnea and the frequent overlap of clinical presentations, particularly in patients with comorbidities like congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The very presence of dyspnea is recognized as an indicator of increased mortality risk, underscoring the importance of thorough evaluation and management.

Learning Objectives

Upon reading this article, clinicians will be able to:

- Recognize the diverse range of conditions that can manifest as breathlessness (dyspnea) in adult patients.

- Outline the essential steps involved in the diagnostic evaluation of dyspnea.

- Delineate the key elements in the differential diagnosis of non-traumatic dyspnea.

Methodology and Prevalence

This review synthesizes information from relevant articles identified through PubMed searches, established guidelines from leading cardiology and pulmonology societies including the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), and authoritative textbooks in general and internal medicine. Search terms employed included “dyspnea,” “epidemiology of dyspnea,” “prevalence of dyspnea in primary care,” “dyspnea guidelines,” “pathophysiology of dyspnea,” “causes of dyspnea,” and terms related to specific conditions such as “dyspnea in acute coronary syndrome” and “dyspnea in COPD.”

Dyspnea is a common presenting complaint across various healthcare settings. Approximately 7.4% of emergency room visits are attributed to dyspnea, while in general practice, 10% of patients report breathlessness during normal activities like walking, and up to 25% when engaging in more strenuous activities such as climbing stairs. For a notable 1–4% of individuals, dyspnea is the primary reason for seeking medical consultation. In specialized settings, chronic dyspnea is a concern for 15–50% of cardiology patients and nearly 60% of pulmonology patients. Furthermore, dyspnea is encountered in 12% of emergency medical service calls, with about half of these patients requiring hospitalization and facing an in-hospital mortality rate of approximately 10%. The spectrum of underlying diagnoses varies depending on the healthcare setting, as detailed in Table 1.

Defining Dyspnea: A Subjective Experience

The American Thoracic Society defines dyspnea as “a subjective experience of breathing discomfort that consists of qualitatively distinct sensations that vary in intensity.” This definition highlights the multifaceted nature of dyspnea, influenced by physiological, psychological, social, and environmental factors, potentially leading to secondary physiological and behavioral responses.

Dyspnea is an encompassing term for various subjective respiratory sensations, including labored breathing, choking sensations, air hunger, and chest tightness. The subjective nature of dyspnea presents a diagnostic challenge, requiring clinicians to discern the underlying cause and severity of the condition. While the precise pathogenesis of dyspnea remains under investigation, current theories involve a regulatory circuit. This circuit integrates afferent signals from chemoreceptors (monitoring pH, CO2, and O2 levels) and mechanoreceptors in muscles and lungs (C fibers in parenchyma, J fibers in bronchi and pulmonary vessels) with the ventilatory response.

Several tools are available for dyspnea assessment, from simple scales like the visual analog scale and Borg scale to comprehensive questionnaires such as the Multidimensional Dyspnea Profile. These validated instruments aid in quantifying and communicating the patient’s experience. Disease-specific classifications, such as the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification for chronic congestive heart failure, also contribute to standardized assessment.

Epidemiology of Dyspnea

Dyspnea is a frequently encountered symptom in both primary care and emergency hospital settings. Studies indicate that a significant percentage of patients presenting to emergency rooms, around 7.4%, report dyspnea as a primary complaint. In general practice, the prevalence is also notable, with 10% of patients experiencing dyspnea during normal walking and 25% during more exertion, like stair climbing. For a subset of patients, dyspnea is the principal reason for seeking medical advice, accounting for 1–4% of consultations. Specialty clinics also see a high volume of dyspnea cases, with cardiologists seeing dyspnea in 15–50% of their patients and pulmonologists in nearly 60%. Emergency medical teams encounter dyspnea in 12% of calls, half of whom require hospitalization with a significant in-hospital mortality rate of approximately 10%. The distribution of underlying causes varies across these different healthcare environments, as detailed in eTable 1.

Diagnostic Evaluation of Dyspnea

Diagnosing dyspnea in clinical practice is often challenging due to its subjective nature and diverse underlying causes. A systematic approach is crucial for effective differential diagnosis.

Initial Assessment: History and Physical Examination

The diagnostic process begins with a detailed patient history and thorough physical examination. Key aspects of the history include the onset, duration, and progression of dyspnea, as well as aggravating and relieving factors. Situational triggers, such as exertion, rest, body position, and emotional stress, are important to identify. Past medical history, including cardiac and pulmonary conditions, allergies, and medications, provides crucial context.

Physical examination should focus on vital signs, including respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation. Auscultation of the lungs to identify adventitious sounds like wheezes or crackles, and cardiac auscultation for murmurs or gallops are essential. Signs of heart failure, such as peripheral edema and jugular venous distention, should be assessed. Table 2 and eTable 1 provide a comprehensive list of symptoms and signs accompanying dyspnea that are significant for differential diagnosis.

Temporal, Situational, and Pathogenetic Criteria

A structured approach to differential diagnosis considers temporal, situational, and pathogenetic factors:

- Temporal Course: Distinguish between acute onset, chronic dyspnea (present for over four weeks), and acute exacerbation of chronic symptoms. Note if dyspnea is intermittent, persistent, or episodic (attacks).

- Situational Aspects: Identify triggers related to rest, exertion, emotional stress, body position (orthopnea, platypnea), and specific exposures.

- Pathogenetic Factors: Categorize potential causes as respiratory system problems (central control, airways, gas exchange), cardiovascular system issues, combined cardiopulmonary causes, or other factors like anemia, thyroid disease, deconditioning, or mental health conditions.

The complexity of diagnosis increases in elderly, multimorbid patients where dyspnea may have multiple contributing factors.

eTable 1. Symptoms and signs accompanying dyspnea that may be of differential diagnostic significance (modified from [3, e4–e6]).

| Additional symptoms and signs | Differential diagnostic considerations |

|---|---|

| Bradycardia | SA or AV block, overdose of drugs that slow the heart rate |

| Brainstem signs, neurologic deficits | brain tumor, cerebral hemorrhage, cerebral vasculitis, encephalitis |

| Cough | nonspecific; mainly reflects diseases affecting the airways and the lung parenchyma |

| Cyanosis | respiratory failure (acute) heart defect with right-to-left shunt, Eisenmenger syndrome (chronic) |

| Diminished or absent breathing sounds | COPD, severe asthma, (tension) pneumothorax, pleural effusion, hematothorax |

| Distention of the neck veins | |

| with rales in the lungs | acutely decompensated congestive heart failure, acute respiratory failure |

| with normal auscultatory findings | pericardial tamponade, acute pulmonary arterial embolism |

| Dizziness, syncope | valvular heart disease (e.g., aortic valvular stenosis), hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy, marked anemia, anxiety disorder, hyperventilation |

| Exhaustion, generalized weakness, exercise intolerance, muscle weakness | anemia, collagenoses, malignant disease (e.g., lung cancer), neuromuscular disease |

| Fever | pulmonary infection, e.g., pneumonia or acute bronchitis, exogenous allergic alveolitis, thyrotoxicosis |

| Heart murmur | cardiac valvular disease |

| Hemodynamic dysfunction: | |

| hypertensive | hypertensive crisis, panic attack, acute coronary syndrome |

| hypotensive | forward heart failure, metabolic disturbance, sepsis, pulmonary arterial embolism |

| Hemoptysis | lung cancer, pulmonary embolism, bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, tuberculosis |

| Hepatojugular reflux | acutely decompensated congestive heart failure |

| Hoarseness | disease of the glottis or trachea, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy |

| Hyperventilation | acidosis, sepsis, salicylate poisoning, psychogenic (incl. anxiety) |

| Impairment of consciousness | psychogenic hyperventilation, brain disease, metabolic disturbance, pneumonia |

| Orthopnea | acute congestive heart failure, toxic pulmonary edema |

| Pain | |

| on respiration | pneumothorax, pleuritis/pleuropneumonia, pulmonary embolism |

| independent of respiration | myocardial infarction, aortic aneurysm, Roemheld syndrome, renal or biliary colic, acute gastritis |

| Pallor | marked anemia |

| Paradoxical pulse | right-heart failure, pulmonary arterial embolism,cardiogenic shock, pericardial tamponade, exacerbation of bronchial asthma |

| Peripheral edema | congestive heart failure |

| Platypnea | hepatopulmonary syndrome, intrapulmonary shunting |

| Rales | pneumonia, acutely decompensated congestive heart failure, acute respiratory failure |

| Stridor | |

| inspiratory | croup, foreign body, bacterial tracheitis |

| expiratory/combined | foreign body, epiglottitis, angioedema |

| Urticaria | Angioedema |

| Use of auxiliary muscles of respiration | (acute) respiratory failure, severe COPD, severe asthma |

| Vegetative symptoms (trembling, cold sweat, etc.) | respiratory failure, anxiety disorder, acute myocardial infarction |

| Wheezes | (exacerbation of) bronchial asthma, COPD, acutely decompensated congestive heart failure, foreign body |

eTable 1 lists symptoms and signs accompanying dyspnea that are significant for differential diagnosis, aiding clinicians in narrowing down potential underlying conditions based on associated clinical findings.

Acute Dyspnea: Recognizing Life-Threatening Conditions

Acute dyspnea can signal life-threatening emergencies. Red flag symptoms include confusion, new-onset cyanosis, breathlessness severe enough to impair speech, and signs of respiratory distress or exhaustion. Immediate assessment of vital signs, particularly heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation, is crucial. Respiratory rate is a key indicator of severity and prognosis, with elevated rates associated with poorer outcomes, including increased ICU admission and mortality.

Delays in diagnosis can lead to prolonged hospitalization and increased mortality. The sudden onset of dyspnea is often profoundly distressing for patients, and emotional factors like panic and anxiety can exacerbate symptoms.

Patient history and accompanying symptoms (Table 2, eTable 1) are vital for identifying the underlying cause of acute dyspnea. eTable 2 lists potential causes of acute dyspnea.

Table 2. Symptoms and signs accompanying dyspnea that may be of differential diagnostic significance*.

| Additional symptoms and signs | Differential diagnostic considerations |

|---|---|

| Diminished or absent breathing sounds | COPD, severe asthma, (tension) pneumothorax, pleural effusion, hematothorax |

| Distention of the neck veins | |

| with rales in the lungs | ADHF, ARDS |

| with normal auscultatory findings | pericardial tamponade, acute pulmonary arterial embolism |

| Dizziness, syncope | valvular heart disease (e.g., aortic valvular stenosis), hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy, marked anemia, anxiety disorder, hyperventilation |

| Hemodynamic dysfunction: | |

| hypertensive | hypertensive crisis, panic attack, acute coronary syndrome |

| hypotensive | forward heart failure, metabolic disturbance, sepsis, pulmonary arterial embolism |

| Hemoptysis | lung cancer, pulmonary embolism, bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, tuberculosis |

| Hyperventilation | acidosis, sepsis, salicylate poisoning, psychogenic (incl. anxiety) |

| Impairment of consciousness | psychogenic hyperventilation, cerebral or metabolic disturbance, pneumonia |

| Orthopnea | acute congestive heart failure, toxic pulmonary edema |

| Pain | |

| on respiration | pneumothorax, pleuritis/pleuropneumonia, pulmonary embolism |

| independent of respiration | myocardial infarction, aortic aneurysm, Roemheld syndrome, renal or biliary colic, acute gastritis |

| Pallor | marked anemia |

| Paradoxical pulse | right-heart failure, pulmonary arterial embolism, cardiogenic shock, pericardial tamponade, exacerbation of bronchial asthma |

| Peripheral edema | congestive heart failure |

| Rales | ADHF, ARDS, pneumonia |

| Use of auxiliary muscles of respiration | respiratory failure/ARDS, severe COPD, severe asthma |

| Wheezes | (exacerbation of) bronchial asthma, COPD, ADHF, foreign body |

*modified from (3, e4– e6), ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrom; ADHF, acutely decompensated heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Table 2 details additional symptoms and signs alongside dyspnea, guiding differential diagnosis in acute settings. It emphasizes the importance of associated findings in identifying potentially life-threatening conditions.

The Role of Biomarkers in Acute Dyspnea

In addition to ECG and chest X-ray, biomarkers play a crucial role in the differential diagnosis of acute dyspnea.

Natriuretic Peptides: BNP and NT-proBNP

Natriuretic peptides, specifically brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), are invaluable for excluding acute congestive heart failure. Elevated levels, particularly above ESC guideline thresholds, strongly suggest heart failure. However, thresholds are lower for patients with chronic heart failure.

Troponins: Markers for Acute Coronary Syndrome

When acute coronary syndrome is suspected, serial measurements of cardiac troponins (troponin I or T) are essential. Elevated troponin levels, exceeding established thresholds, indicate myocardial ischemia. Repeated troponin measurements have a high positive predictive value for acute myocardial ischemia.

D-dimers: Assessing Pulmonary Embolism Risk

D-dimers, fibrin degradation products, are elevated in thrombotic conditions and are useful in evaluating pulmonary embolism. While a negative D-dimer has a high negative predictive value, elevated levels are non-specific. Risk stratification tools like the Wells Score or Geneva Score should be used to assess pre-test probability of pulmonary embolism before ordering D-dimer testing. Age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds (age × 10 µg/L for patients over 50) enhance specificity without compromising sensitivity. A low probability score and normal D-dimer effectively rule out pulmonary embolism.

eTable 3. The Wells score for estimating the probability that pulmonary embolism is present(modified from [19, e7]).

| Original version | Simplified version |

|---|---|

| Prior pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis | 1.5 |

| Heart rate > 100/min | 1.5 |

| Surgery or immobilization in the last 4 weeks | 1.5 |

| Hemoptysis | 1 |

| Active malignant disease | 1 |

| Clinical evidence of deep venous thrombosis | 3 |

| Alternative diagnosis less likely than pulmonary embolism | 3 |

| 3-level classification | ∑ |

| low probability (3.6% [2.0–5.9%]) | 0–1 |

| intermediate probability (20.5% [17.0–24.1%]) | 2–6 |

| high probability (66.7% [54.3–77.6%] | ≥ 7 |

| 2-level classification | ∑ |

| pulmonary embolism unlikely | 0–4 |

| pulmonary embolism likely | ≥ 5 |

eTable 3 presents the Wells Score, a clinical tool used to estimate the pre-test probability of pulmonary embolism. This score aids in deciding whether to pursue further diagnostic testing like D-dimer assay or imaging studies.

Both cardiac troponins and natriuretic peptides can be elevated in pulmonary embolism due to right heart strain. Troponin elevation can occur in various acute pulmonary conditions. Echocardiography is indicated if right heart strain is suspected.

Chronic Dyspnea: Identifying Common Causes

Chronic dyspnea, lasting more than four weeks, is frequently attributed to a limited number of conditions: bronchial asthma, COPD, congestive heart failure, interstitial lung disease, pneumonia, and mental disorders, particularly anxiety and panic disorders. eTable 2 lists a broader range of causes for both acute and chronic dyspnea. In elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, identifying a single cause for chronic dyspnea can be challenging.

eTable 2. Causes of acute and chronic dyspnea (modified from [24]).

| Acute dyspnea | Chronic dyspnea |

|---|---|

| – angioedema – anaphylaxis – infection of the pharynx – vocal cord dysfunction – foreign body – trauma | Head and neckregion,upper airways |

| – rib fractures – flail chest – pneumomediastinum – COPD exacerbation – asthma attack – pulmonary embolism – pneumothorax – pleural effusion – pneumonia – acute respiratory failure – lung contusion/trauma – hemorrhage – lung cancer – exogenous allergic alveolitis | Chest wall, pleura,lungs |

| – acute coronary syndrome/myocardial infarction – acutely decompensated congestive heart failure – pulmonary edema – high-output failure – cardiomyopathy – (tachy-)arrhythmia – valvular heart disease – pericardial tamponade | Heart |

| – stroke – neuromuscular disease | CNS/neuromuscular |

| – organophosphate poisoning – salicylate poisoning – carbon monoxide poisoning – ingestion of other toxic substances – (diabetic) ketoacidosis | Toxic/metabolic |

| – sepsis – fever – anemia – encephalitis – traumatic brain injury – acute renal failure – drugs (e.g., beta-blockers, ticagrelor) – hyperventilation – anxiety – intra-abdominal process – ascites – pregnancy – obesity | Other |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction;

HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; CNS, central nervous system

eTable 2 provides a comprehensive list of causes for both acute and chronic dyspnea, categorized by organ system. This table is a valuable resource for clinicians in considering a broad differential diagnosis.

Patient history, including risk factors, exposures, and prior illnesses (Table 2, eTable 1), often suggests a diagnosis or narrows the differential. However, history alone is diagnostic in only 50-66% of cases. Auscultation and observation of breathing patterns provide further clues. Rapid, shallow breathing suggests interstitial lung disease, while deep, slow breathing is typical of COPD.

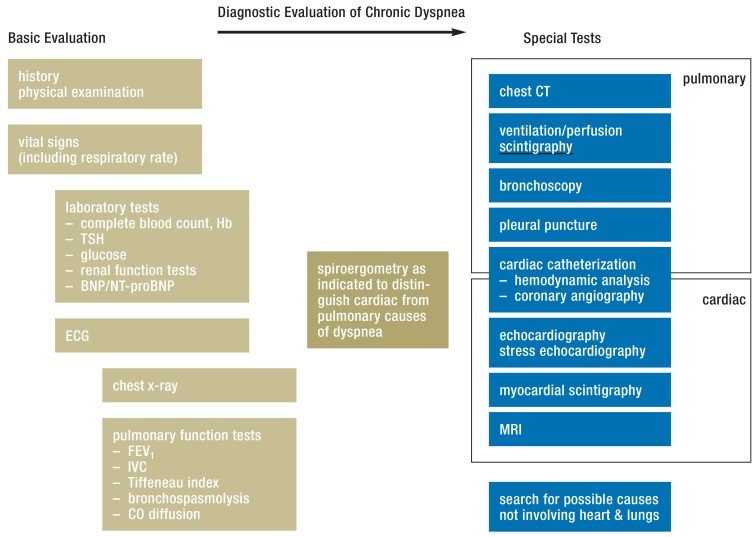

Further diagnostic testing is tailored to individual cases, following a stepwise approach. Spiroergometry can differentiate between cardiac and pulmonary causes. Figure 1 outlines a diagnostic algorithm for chronic dyspnea.

Figure 1.

Figure 1 presents a diagnostic algorithm for chronic dyspnea, guiding clinicians through a step-wise approach to evaluation. It emphasizes initial assessments and subsequent targeted investigations based on clinical findings.

Initial tests may include ECG, chest X-ray, complete blood count, thyroid function tests, and D-dimer. Subsequent testing, guided by initial findings, may involve echocardiography, CT scans, or cardiac catheterization. Selective testing minimizes unnecessary investigations but requires careful clinical judgment to avoid diagnostic delays or overlooking multifactorial dyspnea.

Spiroergometry is valuable in distinguishing cardiac from pulmonary etiologies of dyspnea. Studies have identified FEV1, NT-proBNP levels, and emphysema on CT as independent predictors in dyspnea diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis by Organ System

Respiratory System Diseases

Bronchial Asthma: Characterized by chronic airway inflammation and variable obstruction, asthma presents with recurrent breathlessness episodes, often nocturnal. Triggers include allergens, irritants, exercise, and infections. Expiratory wheezing is typical on auscultation. Spirometry reveals reduced FEV1 and PEF, reversible with bronchodilators. Acute exacerbations feature tachypnea, wheezing, and prolonged expiration.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): COPD is marked by fixed airway obstruction, primarily in smokers over 40. Chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and airflow limitation are key features. Pulmonary function tests show reduced FEV1/IVC (Tiffeneau index < 0.7) and increased residual volume. Chest X-ray may show flattened diaphragms and vascular rarefaction. Exacerbations worsen prognosis. COPD often coexists with heart failure.

Pneumonia: Dyspnea is a major symptom, especially in older adults. Accompanying symptoms include fever, cough, and pleuritic pain. Examination reveals tachypnea, inspiratory crackles, and bronchial breathing. Diagnosis involves inflammatory markers, arterial blood gas analysis (hypoxemia), chest X-ray, and sometimes CT. The CRB-65 score assesses pneumonia severity.

Interstitial Lung Diseases: These present with chronic breathlessness and nonproductive cough, often in smokers. Examination may reveal basal crackles, digital clubbing, and nail changes. Pulmonary function tests show reduced VC and TLC, normal Tiffeneau index, and decreased CO diffusion. Differential diagnosis is complex, requiring pneumonology consultation.

Pulmonary Embolism: Acute pulmonary embolism often manifests with sudden dyspnea, pleuritic pain, and hemoptysis. Examination may reveal tachypnea and tachycardia. Deep vein thrombosis in the legs may be present.

Cardiovascular System Diseases

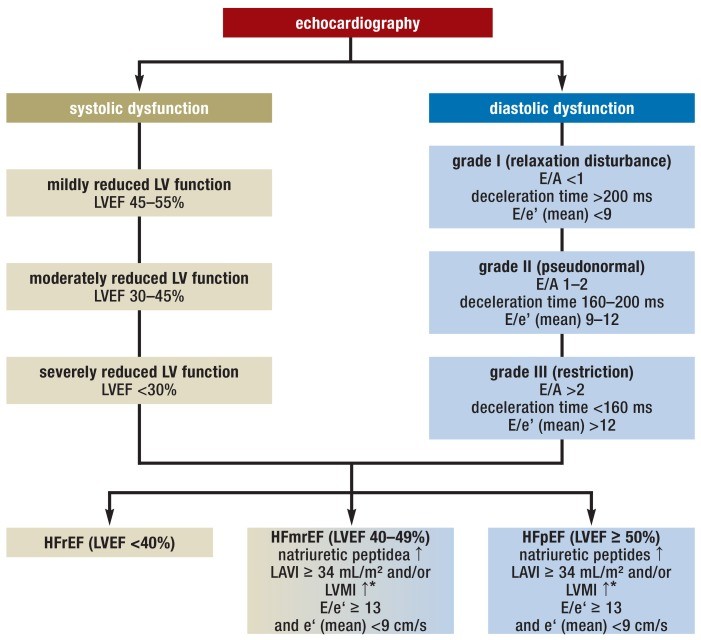

Congestive Heart Failure: Heart failure presents with dyspnea, fatigue, reduced exercise tolerance, and fluid retention. Common causes include coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and valvular disease. Heart failure is classified as HFrEF (reduced ejection fraction), HFpEF (preserved ejection fraction), and HFmrEF (mid-range ejection fraction). Echocardiography is the primary diagnostic tool, assessing systolic and diastolic function (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Figure 2 illustrates echocardiographic criteria for diagnosing heart failure with reduced, mid-range, and preserved ejection fraction (HFrEF, HFmrEF, HFpEF). It highlights key parameters assessed via echocardiography to classify heart failure subtypes.

Coronary Heart Disease: Dyspnea can be an atypical symptom of coronary artery stenosis, even without angina. Exertional dyspnea may be the primary symptom, especially in diabetic patients. Stress testing with imaging (echocardiography, scintigraphy, MRI) and cardiac catheterization are used for diagnosis. Dyspnea is also common in acute coronary syndromes and cardiogenic shock.

Valvular Heart Disease: Valvular diseases, such as aortic stenosis and mitral insufficiency, are significant causes of dyspnea in older adults. Aortic stenosis may present with exertional symptoms, syncope, and angina-like chest pain. Auscultation often reveals a harsh systolic murmur. Mitral insufficiency leads to heart failure symptoms, often with atrial fibrillation. Auscultation reveals a holosystolic murmur. Echocardiography is diagnostic for valvular heart disease.

Other Causes of Dyspnea

Anemia: Anemia, defined by WHO as hemoglobin below 13 g/dL in men and 12 g/dL in women, can cause dyspnea. Diagnostic evaluation is warranted, especially if hemoglobin is below 11 g/dL or unexplainedly decreasing.

Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) Diseases: Upper airway obstruction can cause dyspnea and stridor (inspiratory in supraglottic, expiratory in bronchopulmonary, biphasic at/below glottis compromise). Causes include congenital issues, infections, trauma, tumors, and neurological problems.

Neuromuscular Diseases: Conditions like muscular dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome can cause dyspnea, often with other neurological signs.

Mental Illnesses: Anxiety, panic disorder, and somatization disorders can manifest as dyspnea, diagnosed after excluding organic causes. Improvement with distraction or exercise may suggest a psychological component.

Iatrogenic Causes (Drugs): Medications can induce dyspnea. Non-selective beta-blockers can cause bronchospasm. NSAIDs can promote bronchoconstriction. High-dose aspirin and ticagrelor can also cause dyspnea.

Table 1. The more common causes of dyspnea in emergency medical rescue situations, in hospital emergency rooms, and in general medical practice*.

| Rescue service | Emergency room | General practice |

|---|---|---|

| Heart failure (15–16%) | COPD (16.5%) | Acute bronchitis (24.7%) |

| Pneumonia (10–18%) | Heart failure (16.1%) | Acute upper respiratoryinfection (9.7%) |

| COPD (13%) | Pneumonia (8.8%) | Other airway infection(6.5%) |

| Bronchial asthma (5–6%) | Myocard. infarction (5.3%) | Bronchial asthma (5.4%) |

| Acute coronary syndrome(3–4%) | Atrial fibrillation or flutter(4.9%) | COPD (5.4%) |

| Pulmonary embolism (2%) | Malignant tumor (3.3%) | Heart failure (5.4%) |

| Lung cancer (1–2%) | Pulmonary embolism(3.3%) | Hypertension (4.3%) |

*modified from (6, 8, e3); COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Table 1 compares the prevalence of common dyspnea causes across different healthcare settings: emergency medical services, hospital emergency rooms, and general practice. This comparison highlights setting-specific diagnostic probabilities.

Conclusion: A Multifaceted Approach to Differential Diagnosis

Dyspnea presents a significant diagnostic challenge due to its diverse etiologies and subjective nature. A systematic approach, incorporating detailed history, thorough physical examination, targeted biomarker testing, and appropriate imaging and physiological studies, is essential for accurate differential diagnosis. Clinicians must consider a broad range of potential causes, from respiratory and cardiovascular diseases to systemic illnesses and psychological factors. Rapid and accurate diagnosis is critical for optimizing patient outcomes and reducing morbidity and mortality associated with breathlessness.