Elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is a common clinical finding that often presents a diagnostic challenge for healthcare professionals. ALP, an enzyme found in various tissues throughout the body, is particularly concentrated in the liver and bone. An elevated serum ALP level is frequently associated with hepatobiliary disease, specifically cholestasis, but can also originate from other sources. Cholestasis, derived from the Greek words for bile and standing still, arises from disruptions in bile synthesis, secretion, or flow, whether due to intrahepatic or extrahepatic factors. Characterized by a disproportionate elevation in ALP and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) relative to aminotransferases, cholestasis necessitates a systematic approach to differential diagnosis. This article provides a comprehensive guide to the differential diagnosis of elevated ALP, focusing on cholestatic liver disease and other potential etiologies.

Understanding Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP)

Sources and Physiology of ALP

Alkaline phosphatase is not a single enzyme but rather a group of isoenzymes with optimal activity at alkaline pH levels. While liver and bone are the primary sources of ALP in serum, other tissues such as the intestine, kidney, placenta, and leukocytes also contribute. In the context of liver disease, ALP elevation often reflects increased production by hepatocytes and biliary epithelial cells in response to cholestasis.

Normal vs. Elevated ALP Levels

Normal ranges for ALP can vary slightly depending on age, gender, and laboratory methods. Physiological elevations of ALP are observed during periods of bone growth in children and adolescents, as well as in pregnancy, particularly due to placental ALP. Mild elevations can also occur in healthy individuals, and factors like age (gradual increase between 40-65 years, especially in women), race (higher in African Americans), and blood type (postprandial elevation in blood groups O and B due to intestinal ALP) can influence ALP levels. Pathological elevations, however, warrant further investigation to determine the underlying cause, particularly when coupled with other liver enzyme abnormalities.

Initial Evaluation of Elevated ALP

When encountering an elevated ALP, the initial step is to confirm its hepatic origin and differentiate between cholestatic and hepatocellular patterns of liver enzyme abnormalities.

Confirming Hepatic Origin (GGT, 5’nucleotidase)

To ascertain whether an elevated ALP is indeed hepatic in origin, additional confirmatory tests are essential. Gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) and 5’nucleotidase are enzymes that are also elevated in hepatobiliary disease. Concomitant elevation of GGT or 5’nucleotidase with ALP strongly suggests a hepatic source. Isolated ALP elevation without GGT or 5’nucleotidase increase may point towards non-hepatic sources like bone disease.

Differentiating Cholestatic vs. Hepatocellular Pattern

Liver enzyme patterns can broadly be categorized into hepatocellular, cholestatic, mixed, or infiltrative. A cholestatic pattern is characterized by a disproportionate elevation of ALP and GGT, typically more than 2-3 times the upper limit of normal, with relatively milder elevations in aminotransferases (ALT and AST). In contrast, a hepatocellular pattern is marked by significantly higher elevations in ALT and AST compared to ALP. However, overlap and mixed patterns can occur, necessitating a comprehensive evaluation.

Differential Diagnosis of Cholestasis and Elevated ALP

The differential diagnosis for cholestasis and elevated ALP is broad, encompassing both intrahepatic and extrahepatic conditions.

Intrahepatic Cholestasis

Intrahepatic cholestasis arises from impaired bile excretion within the liver itself, at the hepatocellular or intrahepatic biliary duct level.

Genetic Disorders

Several genetic disorders can disrupt bile transport within hepatocytes and cause intrahepatic cholestasis, often presenting in infancy or childhood.

- Progressive Familial Intrahepatic Cholestasis (PFIC): A group of autosomal recessive disorders characterized by severe cholestasis, pruritus, and elevated bile acids, but typically with low GGT levels (PFIC types 1 and 2). PFIC3, caused by MDR3 mutations, presents with elevated GGT.

- Benign Recurrent Intrahepatic Cholestasis (BRIC): Characterized by intermittent episodes of cholestasis with pruritus and jaundice, also often with low GGT during attacks. BRIC resolves spontaneously between episodes.

- Dubin-Johnson Syndrome: An autosomal recessive disorder caused by MRP2 mutation, leading to conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and cholestasis.

- Cystic Fibrosis: Mutations in the CFTR gene can lead to cholestasis and may be associated with sclerosing cholangitis.

- Alagille Syndrome: A rare genetic disorder characterized by bile duct paucity and cholestasis, often with other systemic features.

Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC) and Autoimmune Cholangiopathy (AIC)

-

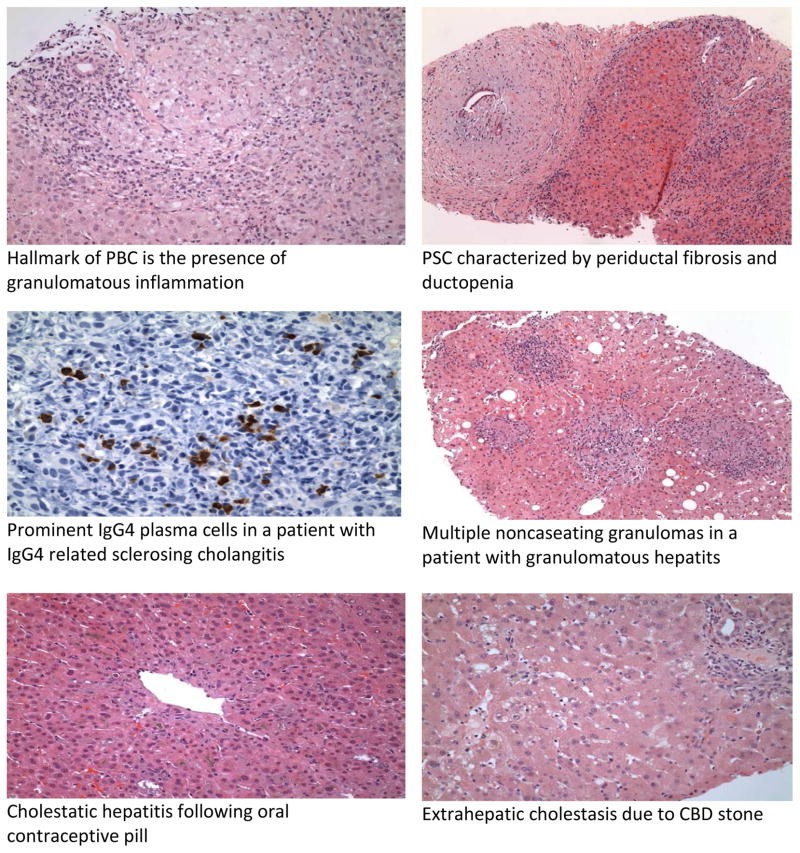

Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC): A chronic autoimmune liver disease primarily affecting women, characterized by progressive destruction of small intrahepatic bile ducts. Hallmarks include elevated ALP and GGT, positive antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) in most cases, and characteristic histological features. Pruritus and fatigue are common symptoms.

Histological features in cholestatic liver disease. This image represents the microscopic changes in liver tissue that can be observed in various cholestatic conditions, aiding in differential diagnosis. -

Autoimmune Cholangiopathy (AIC): Represents AMA-negative PBC, with similar clinical, biochemical, and histological features to PBC but lacking AMA. Other autoantibodies like ANA or SMA may be present.

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC) and IgG4-Related Sclerosing Cholangitis (IgG4-SC)

-

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC): A chronic cholestatic liver disease characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, often associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), particularly ulcerative colitis. Cholangiography (MRCP or ERCP) reveals characteristic multifocal strictures and dilatations (“beading”) of bile ducts. p-ANCA may be positive.

-

IgG4-Related Sclerosing Cholangitis (IgG4-SC): A systemic fibroinflammatory condition that can affect the bile ducts, often mimicking PSC clinically and cholangiographically. However, IgG4-SC is frequently associated with autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) and elevated serum IgG4 levels. Histology shows IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration. Crucially, IgG4-SC is steroid-responsive, unlike PSC.

Feature PSC IgG4-SC Age Younger (25-45 years) Older (around 65 years) IBD Association Common Rare IgG4 Elevation Uncommon Common (70%) Steroid Response No Yes Cholangiography “Beaded” strictures Long strictures, CBD involvement

Hepatic Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis, a multisystemic granulomatous disease, can involve the liver. Hepatic sarcoidosis often presents with elevated ALP and GGT, and serum ACE levels may be elevated. Liver biopsy shows non-caseating granulomas.

Parenteral Nutrition-Associated Liver Disease (PNALD)

Prolonged parenteral nutrition (PN) can lead to liver dysfunction, particularly cholestasis in children. PNALD is characterized by elevated ALP and bilirubin, and ranges from mild enzyme elevations to severe cholestatic injury.

Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy (ICP)

ICP is a pregnancy-specific cholestatic condition presenting with pruritus and elevated serum bile acids and ALP in the late second or third trimester. Symptoms resolve after delivery.

Cholestasis Related to Sepsis

Sepsis can induce cholestasis, often characterized by a disproportionate elevation in bilirubin compared to ALP. This is common in ICU settings and neonatal jaundice.

Drug-Induced Liver Disease (DILI)

Drug-induced liver injury is a significant cause of cholestatic liver disease. Many medications, herbal remedies, and toxins can cause cholestasis. DILI should be considered in any patient with unexplained ALP elevation, and a thorough medication history is crucial. Amoxicillin-clavulanate is a common example of a drug causing cholestatic DILI.

Extrahepatic Cholestasis

Extrahepatic cholestasis results from obstruction of bile flow in the large bile ducts outside the liver.

Choledocholithiasis and Acute Ascending Cholangitis

-

Choledocholithiasis: Gallstones in the common bile duct (CBD) are a frequent cause of extrahepatic obstruction. Symptoms range from asymptomatic to right upper quadrant pain, jaundice, and elevated ALP.

-

Acute Ascending Cholangitis: A severe, life-threatening infection of the biliary system usually caused by CBD obstruction, often by stones. Charcot’s triad (fever, jaundice, RUQ pain) and Reynold’s pentad (including shock and altered mental status) are classic presentations. Markedly elevated ALP and bilirubin are typical.

Choledochal Cyst

Choledochal cysts are congenital dilatations of the bile ducts, more common in Asians and women. They can lead to recurrent cholangitis, pancreatitis, and an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma.

Benign and Malignant Biliary Strictures

-

Benign Biliary Strictures: Can arise from prior biliary surgery, PSC, chronic pancreatitis, or trauma. Present with cholestasis, often with cholangitis.

-

Malignant Biliary Strictures: Most commonly caused by pancreatic cancer, cholangiocarcinoma (including Klatskin tumors), gallbladder cancer, and ampullary cancer. Present with painless jaundice, weight loss, and markedly elevated bilirubin and ALP. CA19-9 levels may be elevated in cholangiocarcinoma.

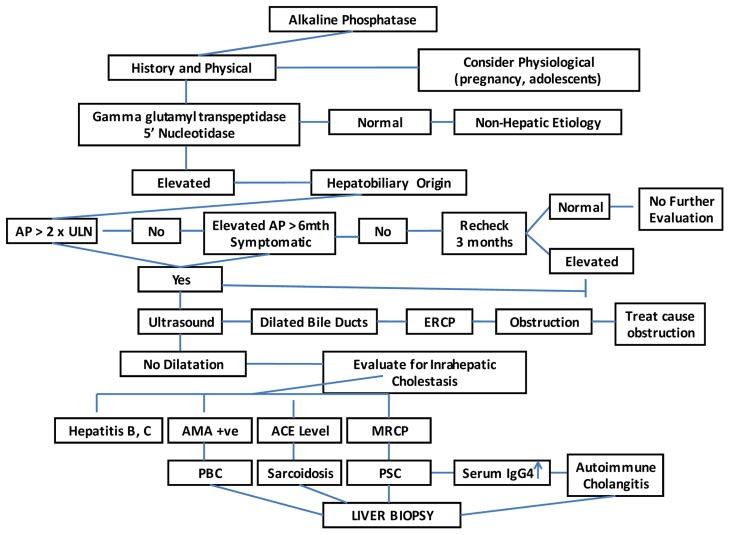

Diagnostic algorithm for workup of elevated alkaline phosphatase. This image provides a visual guide to the stepwise approach in evaluating patients with elevated ALP, starting with initial labs and imaging and progressing to more specialized tests as needed.

Diagnostic Workup Algorithm for Elevated ALP

A systematic approach is crucial for the differential diagnosis of elevated ALP. The diagnostic algorithm typically involves:

- Confirm Hepatic Origin: Assess GGT and 5’nucleotidase levels.

- History and Physical Exam: Detailed history of symptoms (pruritus, jaundice, pain), medications, alcohol use, family history, and physical examination focusing on signs of liver disease and biliary obstruction.

- Liver Function Tests (LFTs): Assess bilirubin, ALT, AST, albumin, and prothrombin time to characterize the pattern of liver injury.

- Imaging:

- Transabdominal Ultrasound (TUS): Initial imaging to assess for biliary dilatation and gallstones.

- CT Scan: Useful for evaluating liver parenchyma, masses, and pancreatic lesions.

- MRCP: Non-invasive imaging of the biliary tree, highly sensitive for biliary strictures and stones.

- ERCP: Gold standard for biliary imaging, allows for therapeutic interventions (stone removal, stenting, biopsy).

- EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound, useful for detecting CBD stones and pancreatic masses.

- Autoantibody Testing: AMA (for PBC), p-ANCA (for PSC), ANA/SMA (for AIC/overlap syndromes), IgG4 levels (for IgG4-SC).

- Liver Biopsy: May be necessary for definitive diagnosis, particularly in intrahepatic cholestasis, to assess histology and rule out other conditions.

- Genetic Testing: Considered in suspected genetic cholestatic disorders, especially in children.

Management of Cholestasis-Related Symptoms

Managing symptoms associated with cholestasis is an important aspect of patient care.

Pruritus

Pruritus is a common and distressing symptom. Management strategies include:

- Cholestyramine: First-line resin that binds bile acids in the gut.

- Rifampin: Reduces hepatic bile acid uptake and increases renal excretion.

- Naltrexone: Opioid antagonist that can alleviate pruritus.

- Sertraline/Paroxetine: Antidepressants that may be helpful in some cases.

- Plasmapheresis: Reserved for refractory pruritus.

- Liver Transplantation: Considered for intractable pruritus.

Fatigue

Fatigue is a challenging symptom with no definitively effective therapy. Modafinil or low-dose amitriptyline may offer some benefit.

Osteoporosis

Calcium and Vitamin D supplementation are recommended. Bisphosphonates are used to treat established osteoporosis.

Fat-Soluble Vitamin Deficiencies

Vitamins A, D, E, and K levels should be monitored and supplemented as needed.

Hyperlipidemia

Statins may be used cautiously with liver enzyme monitoring. Plasmapheresis can be considered for severe hypercholesterolemia.

Conclusion

Elevated alkaline phosphatase is a frequent laboratory abnormality that necessitates a thorough diagnostic evaluation. A systematic approach, incorporating clinical history, biochemical testing, and appropriate imaging, is essential to accurately determine the underlying cause of elevated ALP and guide management. Differential diagnosis should consider a wide spectrum of conditions, including both intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholestatic disorders, as well as non-hepatic sources. Understanding the nuances of each condition and utilizing a stepwise diagnostic algorithm ensures optimal patient care and targeted therapy.