Introduction

Spinal stenosis, a common condition, often presents with symptoms that can be elusive in physical examinations [1, 2]. Diagnosis hinges primarily on patient-reported symptoms, frequently reinforced by imaging findings. However, the symptomatology of vitamin B12 deficiency shares significant overlap with spinal stenosis, including paresthesia, ataxia, and various neurological disturbances. Untreated vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to irreversible neurological damage. It’s also important to note that diabetic patients, particularly those on metformin, face an elevated risk of vitamin B12 deficiency [3].

Radiographic evidence of spinal disorders is extensively documented, demonstrating high sensitivity and specificity in symptomatic individuals. Yet, degenerative spinal changes are prevalent across the general population [1, 2]. Studies reveal a high incidence (20–76%) of lumbar disc abnormalities [4] and MRI-detected cervical spinal cord compression in asymptomatic individuals [5].

Interpreting spinal imaging requires careful correlation with patient history and clinical examination. Radiographic signs of spinal stenosis may not always align with patient symptoms, and conversely, neurological symptoms may not always stem from spinal issues despite suggestive imaging.

Patients referred for spinal assessments may not have undergone thorough primary care investigations. Consequently, reversible causes of peripheral neuropathy might be overlooked. Identifying these patients is critical to prevent unnecessary investigations and surgeries, and more importantly, to ensure accurate diagnoses and appropriate treatments are implemented. Clinical assessment should prioritize distinguishing features. Walking distance is a key differentiator. While peripheral neuropathy can impair walking due to sensory loss, spinal claudication with a defined claudication distance is more specific to spinal stenosis.

Establishing a diagnosis often involves ruling out other conditions. Specialized spinal surgery practices may inadvertently focus on spinal explanations for symptoms, especially when supported by imaging. However, in cases with predominantly sensory symptoms, non-surgical causes must be considered and excluded through a robust differential diagnosis in primary care.

Conditions like diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency, and other nutritional deficits are among the numerous causes of peripheral neuropathy [6, 7] (Table 1). These can manifest as symmetrical peripheral neuropathy or mononeuropathy, with varying combinations of sensory disturbances and weakness, potentially mimicking spinal stenosis. Simple blood tests can effectively investigate these conditions, and appropriate treatment can often alleviate patient symptoms.

Table 1. Causes of Peripheral Neuropathy

| Investigations |

|---|

| Trauma |

| Systemic disease |

| Diabetes |

| Kidney failure |

| Liver disease |

| Alcoholism |

| Hypothyroidism |

| Vitamin deficiencies |

| Autoimmune disorders (SLE, RA) |

| Drugs (vincristine, metronidazole, amiodarone, phenytoin) |

| Neoplasia |

| Infections |

| HIV/AIDS |

| Syphillis |

| Guillain–Barre syndrome |

| Inherited |

| Charcot–Marie–Tooth syndrome |

| Friedreich’s ataxia |

EMG Electromyography studies, NCS nerve conduction studies, FBC full blood count, EBV Epstein–Barr virus, CMV cytomegalovirus, VZV Varicella Zoster virus. Most listed disorders should be evident from patient history if diagnosed. Investigations listed are not exhaustive. Basic haematological and biochemical tests should be ordered.

Vitamin B12, a water-soluble vitamin, is crucial for cellular metabolism, DNA synthesis, fatty acid regulation, nervous system function, and blood cell production. Deficiency disrupts the balance of myelinotoxic and myelinotrophic factors in cerebrospinal fluid, contributing to neuropathy [8]. Conversely, vitamin B12 has shown promise in alleviating neuropathic pain in diabetic rats [9] and even outperformed nortriptyline in treating diabetic peripheral neuropathy, even in cases with normal B12 levels [10].

This study aims to emphasize the importance of considering vitamin B12 deficiency in patients presenting to spinal surgery outpatient clinics. Addressing this comorbidity can improve patient outcomes. The study sought to determine the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in spinal surgery referrals and assess subsequent patient management.

Methodology

This retrospective cohort study was conducted in a University Hospital outpatient setting and registered locally.

All patients screened for vitamin B12 levels over four years (2005–2008) were identified. Patients with abnormal results were further examined. Repeat testing and imaging reports were reviewed for dual pathology. A structured telephone survey assessed patient outcomes. Primary care clinicians were contacted to obtain current clinical records.

Results

Approximately 1800 new outpatients were seen annually. The study population comprised 457 patients (229 males, 228 females) tested for vitamin B12 levels. 39 (8.5%) were vitamin B12 deficient (26 males; average age 63, range 23–83). Two deceased patients and three with unobtainable contact details were excluded, leaving 34 for the telephone survey.

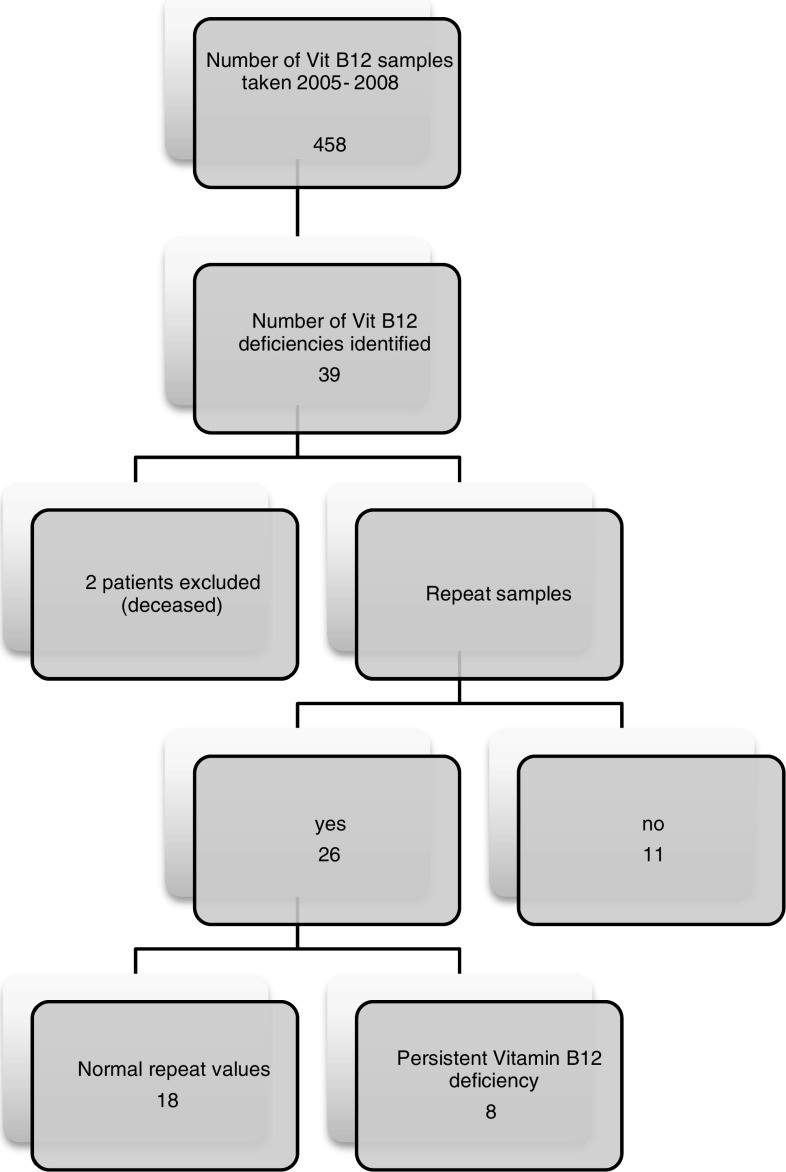

26 of 37 patients had repeat vitamin B12 levels, with 8 remaining deficient. 11 patients lacked repeat testing. 19 B12-deficient patients did not receive adequate replacement therapy (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Vitamin B12 Deficiency Patient Follow-up

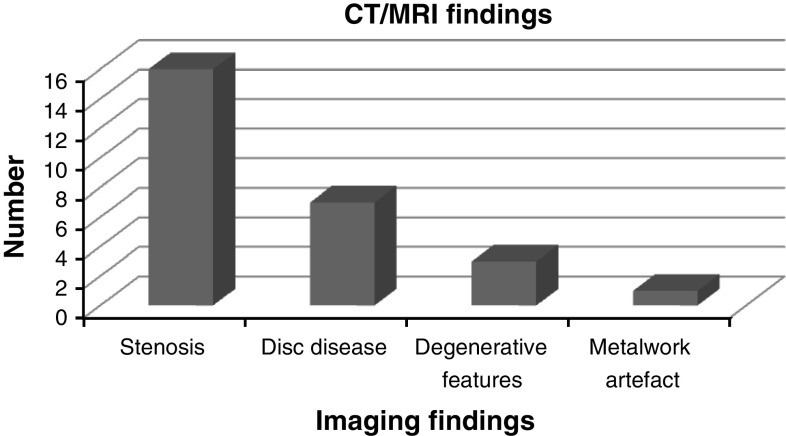

27 of 37 vitamin B12 deficient patients underwent spine MRI or CT imaging (5 cervical, 22 lumbar). While all showed degenerative changes, 59% had documented spinal stenosis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Imaging Findings in Vitamin B12 Deficient Patients

Phone Survey Results

Of 39 patients, 5 were excluded (2 deceased, 3 unreachable), yielding 34 (87% follow-up). 25 received vitamin B12 supplementation, 9 did not. Patients graded treatment response using a global outcome score (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Global Outcome Scores in Vitamin B12 Deficient Patients

72% on treatment reported improved outcomes (much better/better) versus 55% without supplementation. Among those reporting ‘better’ symptoms, 7 of 16 on supplements and 2 not supplemented lacked follow-up B12 levels, making treatment adequacy unclear (P > 0.05, Fisher’s test).

Discussion

Vitamin B12 deficiency can produce neurological symptoms resembling spinal stenosis, complicating clinical assessments. In an era of readily accessible imaging, MRI or CT scans might become the primary investigation, potentially overlooking reversible causes. This can significantly impact surgical patients, as failure to identify and treat reversible conditions may lead to irreversible neurological damage. Effective treatment aims for rapid patient improvement. Unidentified comorbidities delay recovery and can impair surgical outcomes. Persistent post-operative symptoms also incur costs for further investigations and ongoing disability. Ideally, reversible causes should be investigated before specialist spinal referrals. A holistic medical approach is crucial, moving beyond a narrow focus on operative spinal disorders in specialized clinics. Suspicion should be raised by descriptions of ‘burning’ pain, diabetic patients (especially on metformin), and sensory symptoms at rest, prompting metabolic investigations. Risk factors for B12 deficiency (Table 2) and other peripheral neuropathy causes (Table 1) from patient history should also alert clinicians. These should be investigated and treated before considering high-risk spinal procedures, emphasizing the importance of differential diagnosis in primary care.

Table 2. Causes of Vitamin B12 Deficiency [13]

| Pernicious anaemia |

|---|

| Dietary deficiency |

| Malabsorption |

| Crohn’s disease |

| Chronic pancreatitis |

| Whipple’s disease |

| Parasitic infections |

| Post surgical malabsorption |

| Gastrectomy |

| Terminal ileal resection |

| Food B12 malabsorption (inability to release B12 from food or intestinal transport proteins) |

| Atrophic gastritis |

| Chronic H. Pylori infection |

| Long terms antacid use |

| Chronic alcoholism |

| Idiopathic |

This study’s findings are fourfold. First, the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in this spinal patient subgroup was 8%. Only around 6% of all spine outpatient attendees were tested for B12 levels. No specific protocol existed for B12 testing. This audit suggests that patients ‘at risk’ with sensory disturbances should be investigated for reversible peripheral neuropathy causes. Standard practice in our clinics now includes basic haematological, biochemical, and endocrine tests for such patients, alongside or before specialized imaging, improving differential diagnosis in primary care.

Second, all imaged patients had spinal pathology, mostly spinal stenosis and intervertebral disc disease. Degenerative changes commonly coexisted. Vitamin B12 deficient patients also had coexisting spinal pathologies, potentially contributing to symptoms individually or combined.

Third, 72% of supplemented patients reported symptom improvement versus 55% without supplementation, although not statistically significant. While the global outcome score measures subjective perception, the lack of objective measures and small patient numbers limit definitive conclusions. Nonetheless, identifying and treating B12 deficiency is vital for addressing peripheral neuropathy and preventing hematological and biochemical disturbances.

Fourth, 26% of deficient patients received no supplementation. 30% lacked repeat B12 level tests, and 22% remained deficient, indicating inadequate therapy. Current clinic practice involves informing general practitioners of abnormal results and delegating treatment to primary care. However, these results highlight communication or treatment implementation failures, with medicolegal and patient wellbeing implications. This underscores the critical role of primary care in the ongoing management and differential diagnosis of these patients.

Vitamin B12 deficiency, along with other biochemical and endocrine abnormalities, can complicate the clinical assessment of patients with spinal disorder features, particularly with confirmed spinal stenosis. This emphasizes the importance of differential diagnosis in primary care to avoid misattributing symptoms solely to spinal pathology.

Cross-sectional studies report vitamin B12 deficiency prevalence from 12% [11] to 44% [12] in those over 65, predominantly affecting males and increasing with age [11]. This parallels spinal stenosis prevalence and age-related degenerative imaging findings [1, 2]. Given these parallels and symptom similarities, B12 levels should be assessed in all patients with spinal stenosis features, even with positive imaging, to ensure comprehensive differential diagnosis in primary care.

We acknowledge this retrospective study’s limitations, especially selection bias from only 6% B12 testing. The reason is unclear, but pre-audit, no consensus existed on biochemical investigations for reversible peripheral neuropathy causes. Patients with sensory disturbances or ‘burning’ pain and non-specific neurological symptoms were likely preferentially investigated, introducing selection bias. Quantifying this is impossible with our data. Current practice involves assessing vitamin B12, folate, glucose, and other biochemical abnormalities in all patients with sensory disturbances, even with pathological MRI findings. These abnormalities are now corrected before more invasive procedures, improving the overall approach to differential diagnosis in primary care.

Conclusion

In older patients with sensory symptoms, B12 deficiency should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis in primary care. Detecting and treating deficiency improves global outcomes compared to no treatment.

Despite blood abnormalities, some patients missed therapy due to communication failures. Without correct blood tests, pathology remains undetected, and patients may continue with primary symptoms despite high-risk spinal surgeries. This highlights the vital role of accurate and thorough differential diagnosis in primary care settings to optimize patient outcomes and avoid unnecessary interventions.

Acknowledgments

No funding was required for this project.

Conflict of interest

None.