Breathlessness, or dyspnea, is a prevalent symptom encountered across various healthcare settings, affecting up to 25% of ambulatory patients. Its diverse etiology, ranging from benign conditions to life-threatening emergencies, necessitates a systematic and efficient diagnostic approach. Understanding the Differential Diagnosis Of Breathlessness is crucial for timely intervention and improved patient outcomes. This article provides an in-depth guide to the differential diagnosis of breathlessness, aiming to enhance clinical acumen and diagnostic precision.

Understanding Dyspnea: Definition and Prevalence

Dyspnea, as defined by the American Thoracic Society, is a “subjective experience of breathing discomfort.” This encompasses a spectrum of sensations, including labored breathing, air hunger, and chest tightness. The subjective nature of dyspnea presents a diagnostic challenge, requiring clinicians to navigate both physiological and psychological factors influencing a patient’s perception.

Dyspnea is a common presenting complaint, with significant epidemiological impact. Emergency room visits attribute dyspnea as a primary symptom in approximately 7.4% of cases. In general practice, the prevalence is even higher, with up to 25% of patients reporting dyspnea upon exertion. Specialty clinics focusing on cardiology and pulmonology see dyspnea as a chief complaint in a substantial proportion of their patient population, ranging from 15% to 60%. The presence of dyspnea is not merely a symptom; it is an independent predictor of increased morbidity and mortality, underscoring the importance of accurate and prompt diagnosis.

Diagnostic Evaluation: A Step-by-Step Approach

Evaluating breathlessness demands a structured approach, integrating history, physical examination, and targeted investigations. The diagnostic journey begins with a detailed patient history, focusing on the temporal pattern of dyspnea (acute vs. chronic), situational triggers (exertion, rest, body position), and associated symptoms.

History and Physical Examination

A thorough history should elucidate:

- Onset and Duration: Acute dyspnea (<4 weeks) warrants immediate attention due to potentially life-threatening causes, while chronic dyspnea (>4 weeks) necessitates investigation into underlying chronic conditions.

- Provoking and Palliative Factors: Identifying triggers like exertion, allergens, or body position (orthopnea, platypnea) can provide crucial diagnostic clues.

- Associated Symptoms: Cough (productive or non-productive), chest pain (pleuritic or cardiac), wheezing, edema, fever, and palpitations are vital in narrowing the differential diagnosis.

- Past Medical History: Pre-existing conditions like asthma, COPD, heart failure, anemia, and mental health disorders are significant risk factors and potential causes of dyspnea.

- Medications and Exposures: A detailed medication list, including over-the-counter drugs and supplements, and occupational/environmental exposures can reveal iatrogenic or environmental causes.

- Smoking History: Pack-years of smoking are critical in assessing the risk for COPD and lung cancer.

The physical examination should focus on:

- Vital Signs: Respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation are essential for initial assessment of severity and stability. Tachypnea is a strong indicator of acute distress and poorer prognosis.

- Respiratory System: Auscultation for breath sounds (wheezes, rales, diminished sounds), percussion for resonance, and observation of breathing pattern (rapid shallow, deep slow, use of accessory muscles) provide insights into pulmonary pathology.

- Cardiovascular System: Auscultation for heart sounds (murmurs, gallops), assessment of jugular venous distention (JVD), and examination for peripheral edema are crucial for evaluating cardiac causes.

- General Examination: Look for signs of anemia (pallor), cyanosis (central or peripheral), clubbing of fingers, and neurological deficits.

Initial Investigations

Based on the initial assessment, basic investigations are crucial in guiding the differential diagnosis of breathlessness. These may include:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): To detect cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial ischemia, or right heart strain.

- Chest X-ray: To identify pneumonia, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, pulmonary edema, or lung masses.

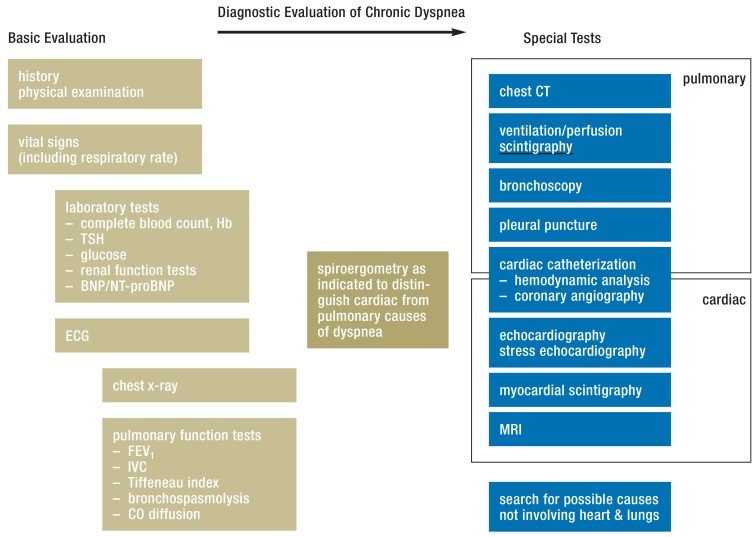

Diagnostic Algorithm for Chronic Dyspnea. Modified from (3, 9, 22, 24) BNP: brain natriuretic peptide, CT: computed tomography, ECG: electrocardiography, FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second, Hb: Hemoglobin IVC: inspiratory vital capacity, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, NT-proBNP: N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide, TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone.

- Laboratory Tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To assess for anemia, infection.

- Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH): To rule out thyroid dysfunction.

- D-dimer: To evaluate for pulmonary embolism in acute dyspnea, particularly when pre-test probability is intermediate or low.

- Biomarkers (BNP/NT-proBNP, Troponin): Crucial in differentiating cardiac from pulmonary causes, especially in acute settings.

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Dyspnea

Acute breathlessness demands rapid assessment and exclusion of life-threatening conditions. Key alarm symptoms include confusion, cyanosis, inability to speak in full sentences, and respiratory distress.

Life-Threatening Causes of Acute Dyspnea

- Pulmonary Embolism (PE): Sudden onset dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, tachycardia, and hypoxemia are suggestive. Risk factors and Wells score should guide D-dimer testing and further imaging (CT pulmonary angiography).

- Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS): Dyspnea can be an anginal equivalent, particularly in elderly, diabetics, and women. Chest pain, ECG changes, and elevated troponins are diagnostic.

- Pneumothorax: Sudden onset dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain, with decreased breath sounds on one side, are characteristic. Chest X-ray confirms the diagnosis.

- Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (ADHF): Rapid onset dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, rales, and edema are typical. Elevated BNP/NT-proBNP levels are supportive.

- Severe Asthma Exacerbation: Wheezing, chest tightness, cough, and use of accessory muscles are common. Peak expiratory flow (PEF) measurement assesses severity.

- Anaphylaxis and Angioedema: Rapid onset dyspnea with urticaria, angioedema, and stridor suggests airway compromise.

- Pneumonia: Acute onset dyspnea with fever, cough, sputum production, and pleuritic chest pain. Chest X-ray confirms consolidation.

Biomarkers in Acute Dyspnea

Biomarkers play a crucial role in the differential diagnosis of acute dyspnea, particularly in differentiating cardiac and pulmonary etiologies.

-

Natriuretic Peptides (BNP, NT-proBNP): Elevated levels strongly suggest heart failure as the cause of acute dyspnea. They are highly sensitive for ruling out ADHF, especially when using guideline-recommended cut-off values.

-

Troponins: Elevated cardiac troponins indicate myocardial injury and are essential in diagnosing ACS. Serial measurements are recommended to assess for dynamic changes. Troponin elevation can also occur in PE with right heart strain, and in other acute pulmonary conditions.

-

D-dimer: A normal D-dimer level, in conjunction with low or intermediate pre-test probability (e.g., Wells score), effectively rules out PE. Age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds improve specificity in older patients.

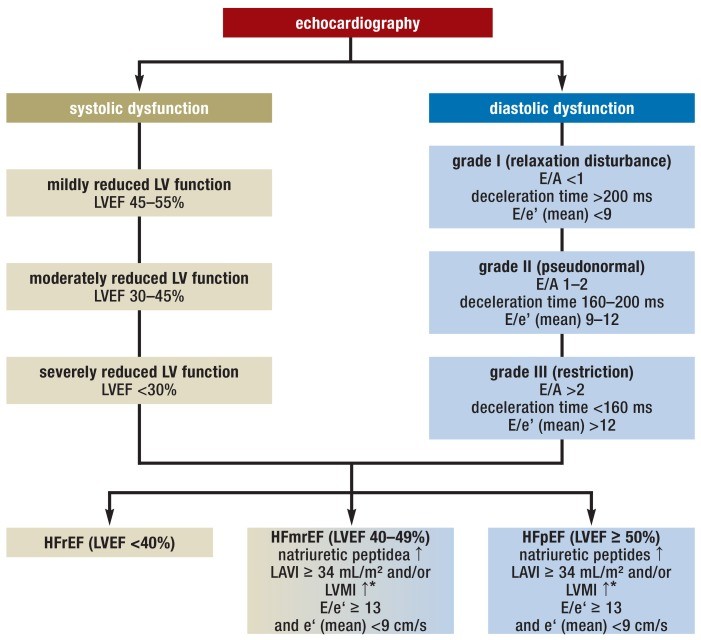

Echocardiographic criteria for congestive heart failure with reduced or preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (HFrEF and HFpEF, respectively) and the new category with so-called mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF); modified from (17, 38). LV: left ventricular, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, LAVI: left atrial volume index, LVMI: left ventricular mass index, (?*: =115 g/m² for men, = 95 g/m² for women), E: maximal speed of E-wave in inflow profile over the mitral valve, A: maximal speed of A-wave in inflow profile over the mitral valve, e’(mean): mean maximal (early) diastolic speed of the septal and lateral mitral valve annulus (tissue Doppler).

Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Dyspnea

Chronic breathlessness, persisting for more than four weeks, often arises from chronic cardiopulmonary conditions, but also consider non-cardiopulmonary causes.

Common Causes of Chronic Dyspnea

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): Progressive dyspnea, chronic cough, sputum production, and smoking history are hallmarks. Spirometry demonstrates airflow obstruction.

- Asthma: Episodic dyspnea, wheezing, cough, and variable airflow obstruction on spirometry. Bronchodilator reversibility is characteristic.

- Heart Failure (Chronic): Exertional dyspnea, fatigue, edema, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. Echocardiography assesses systolic and diastolic function.

- Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD): Progressive dyspnea, dry cough, and inspiratory crackles on auscultation. Pulmonary function tests show restrictive pattern and reduced diffusion capacity. High-resolution CT chest is often needed for diagnosis.

- Anemia: Chronic dyspnea, fatigue, pallor, and tachycardia. CBC reveals low hemoglobin levels.

- Mental Health Disorders (Anxiety, Panic Disorder): Dyspnea can be a somatic manifestation. Diagnosis of exclusion after thorough medical evaluation.

Differentiating Cardiac and Pulmonary Causes of Chronic Dyspnea

Often, clinical history and examination suggest the primary organ system involved. However, distinguishing between cardiac and pulmonary dyspnea can be challenging, especially in patients with comorbidities.

- Spiroergometry (Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing – CPET): This comprehensive test assesses ventilatory and cardiovascular responses to exercise, helping differentiate between cardiac and pulmonary limitations. It measures oxygen uptake (VO2), carbon dioxide output (VCO2), and ventilatory parameters during exercise.

- Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs): Spirometry, lung volumes, and diffusion capacity help characterize pulmonary pathology (obstruction, restriction, emphysema).

- Echocardiography: Evaluates cardiac structure and function, including ejection fraction, diastolic function, and valvular abnormalities.

Dyspnea Due to Diseases Outside the Cardiopulmonary Systems

While cardiopulmonary diseases are the most frequent causes of dyspnea, clinicians must consider other systemic conditions.

- Anemia: Reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of blood leads to exertional dyspnea.

- Neuromuscular Diseases: Conditions like myasthenia gravis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Guillain-Barré syndrome can weaken respiratory muscles, causing dyspnea.

- Thyroid Disorders: Both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism can manifest with dyspnea.

- Obesity: Excess weight can restrict chest wall movement and increase metabolic demand, leading to dyspnea, especially on exertion.

- Psychogenic Dyspnea: Anxiety and panic disorders can present with breathlessness, often described as air hunger or chest tightness. This diagnosis requires exclusion of organic causes.

- Medications: Beta-blockers (non-selective), NSAIDs, and certain platelet inhibitors like ticagrelor can induce or exacerbate dyspnea in susceptible individuals.

Conclusion: Navigating the Diagnostic Challenge of Breathlessness

The differential diagnosis of breathlessness is a complex clinical endeavor, demanding a systematic approach and broad clinical knowledge. A detailed history, thorough physical examination, and judicious use of investigations, including biomarkers and specialized tests like spiroergometry, are essential to navigate this diagnostic challenge. Recognizing both life-threatening and chronic causes, as well as considering non-cardiopulmonary etiologies, is paramount for providing optimal patient care and improving outcomes in individuals presenting with breathlessness. Rapid evaluation and accurate diagnosis are not only crucial for reducing mortality but also for alleviating patient distress and improving quality of life.

Table 1. Common Causes of Dyspnea Across Different Healthcare Settings

| Setting | Most Common Causes |

|---|---|

| Emergency Medical Services | Heart Failure, Pneumonia, COPD, Asthma, ACS, PE |

| Emergency Room | COPD, Heart Failure, Pneumonia, Myocardial Infarction, Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter, PE |

| General Practice | Acute Bronchitis, Upper Respiratory Infections, Asthma, COPD, Heart Failure, Hypertension |

Modified from (6, 8, e3); COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ACS: Acute Coronary Syndrome, PE: Pulmonary Embolism.

References

[1] American Thoracic Society. (2012).呼吸困难:定义和测量。美国胸科学会共识报告。美国呼吸与危重症医学杂志,185(4),435-447。

[2] Manning, H. L. 和 Schwartzstein, R. M. (2016)。呼吸困难。新英格兰医学杂志,375(14),1317-1327。

[3] Simon, P. M., 和 Breen, P. H. (2023)。呼吸困难的评估。UpToDate。检索自 https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-dyspnea-in-adults