Background

Dyspnea, commonly known as shortness of breath, is a prevalent symptom affecting a significant portion of ambulatory patients, with estimates reaching as high as 25%. This symptom is not disease-specific and can stem from a wide array of underlying medical conditions, some of which pose immediate threats to life.

Methods

This review synthesizes information from relevant scholarly articles identified through targeted PubMed searches, alongside established clinical practice guidelines, to provide a current perspective on dyspnea diagnosis.

Results

Dyspnea is a subjective experience characterized by varying sensations related to breathing discomfort, often influenced by a patient’s emotional state. For diagnostic purposes, dyspnea is categorized by onset: acute (sudden) or chronic (persisting beyond four weeks). While patient history, physical examination, and observation of breathing patterns are crucial first steps, a definitive diagnosis often necessitates further investigation in 30–50% of cases. This may include biomarker analysis and other ancillary diagnostic tests, especially when multiple conditions might be contributing to the symptom. The etiology of dyspnea is diverse, encompassing cardiac and pulmonary diseases such as congestive heart failure, acute coronary syndromes, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), as well as systemic conditions like anemia and mental health disorders.

Conclusion

The broad spectrum of potential causes for dyspnea presents a considerable diagnostic challenge. Timely and accurate evaluation is essential for effective patient management, aiming to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with this common and often distressing symptom.

Dyspnea, or the sensation of shortness of breath, is a frequent complaint in outpatient settings, impacting up to 25% of patients. Its clinical significance is underscored by the fact that it can be a primary indicator of acute, life-threatening conditions such as pulmonary embolism or acute myocardial infarction. Therefore, a swift and methodical diagnostic approach is critical. The complexity of diagnosing dyspnea is further compounded by overlapping clinical presentations and the frequent coexistence of comorbid conditions, for example, the overlap between congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The subjective nature of dyspnea, encompassing a range of individual experiences, adds another layer of complexity. Importantly, the presence of dyspnea itself is recognized as an independent predictor of increased mortality, highlighting the importance of accurate diagnosis and management.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this article, readers should be able to:

- Recognize the common medical issues that lead adult patients to experience and report dyspnea.

- Outline the essential steps involved in the diagnostic evaluation process for patients presenting with dyspnea.

- Identify the key elements in the differential diagnosis of dyspnea of non-traumatic origin.

Diagnostic Methods for Dyspnea

Prevalence of Dyspnea

Dyspnea is a widespread symptom, commonly encountered in both primary care and emergency medical environments. Studies indicate that approximately 7.4% of emergency room visits are due to dyspnea. In general practice, the prevalence is even higher, with 10% of patients reporting dyspnea during normal activities like walking on level ground, and 25% experiencing it with more strenuous activities such as climbing stairs. For a notable proportion of patients, ranging from 1% to 4%, dyspnea is the primary reason for seeking medical consultation. In specialized medical settings, chronic dyspnea is a frequent concern, accounting for 15–50% of cardiology patient visits and nearly 60% of pulmonology consultations. Furthermore, dyspnea is a significant issue in pre-hospital care, affecting 12% of emergency medical service responses, with half of these patients requiring hospitalization and facing an in-hospital mortality rate of approximately 10%. The distribution of underlying causes for dyspnea varies depending on the healthcare setting, as detailed in Table 1.

Illustrative Case Study

Consider a 64-year-old female patient who consults her primary care physician due to gradually worsening shortness of breath upon exertion. She reports being unable to climb more than two flights of stairs without needing to stop and can only walk for about five minutes on level ground before feeling “exhausted”. While she has experienced shortness of breath for some time, she notes a significant increase in severity over the past few days.

Defining Dyspnea

The American Thoracic Society, in a consensus statement, defines dyspnea as “a subjective experience of breathing discomfort that consists of qualitatively distinct sensations that vary in intensity.” This definition acknowledges that dyspnea arises from a complex interplay of physiological, psychological, social, and environmental factors, potentially leading to secondary physiological and behavioral responses.

Dyspnea is an overarching term encompassing various distinct subjective breathing experiences, including labored breathing, feelings of suffocation or choking, and an unsatisfied need for air. The subjective nature of dyspnea poses a significant challenge for clinicians in accurately diagnosing the underlying condition and assessing its severity. The precise mechanisms of dyspnea are still under investigation, with current theories focusing on a regulatory feedback loop. This loop involves afferent signals sent centrally from chemoreceptors (monitoring pH, CO2, and O2 levels) and mechanoreceptors in respiratory muscles and lungs (including C fibers in the parenchyma and J fibers in bronchi and pulmonary vessels), which then trigger a ventilatory response.

Various tools are available for assessing dyspnea, ranging from simple intensity scales (visual analog scale, Borg scale) to comprehensive multidimensional questionnaires like the Multidimensional Dyspnea Profile. These validated instruments facilitate effective communication about dyspnea. Disease-specific classifications also exist, such as the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification for chronic congestive heart failure.

The Diagnostic Challenge of Dyspnea

Diagnosing dyspnea in clinical practice is often complex, primarily because the term “dyspnea” or “shortness of breath” encompasses a wide range of subjective patient experiences.

Epidemiology of Dyspnea

Dyspnea is a common symptom across different healthcare settings, from general practice to hospital emergency departments. Reports indicate that approximately 7.4% of emergency department visits are attributed to complaints of dyspnea. In primary care settings, around 10% of patients report dyspnea when walking on level surfaces, and this number increases to 25% when considering more strenuous activities like climbing stairs. For a notable segment of patients (1–4%), dyspnea is the primary reason for seeking medical attention. In specialized medical practices, dyspnea is a significant concern, affecting 15–50% of patients seen by cardiologists and nearly 60% of those consulting pulmonologists. Emergency medical services also frequently encounter dyspnea, with 12% of calls involving this symptom, half of which result in hospital admission. Among hospitalized patients with dyspnea, the in-hospital mortality rate is approximately 10%. The distribution of underlying diagnoses for dyspnea varies depending on the specific healthcare setting, as illustrated in eTable 1.

eTable 1. Symptoms and Signs Accompanying Dyspnea and Their Differential Diagnostic Significance (Adapted from [3, e4–e6]).

| Additional Symptoms and Signs | Differential Diagnostic Considerations |

|---|---|

| Bradycardia | SA or AV block, drug overdose (heart rate slowing) |

| Brainstem signs, Neurologic deficits | Brain tumor, cerebral hemorrhage, cerebral vasculitis, encephalitis |

| Cough | Non-specific; primarily diseases of airways and lung parenchyma |

| Cyanosis | Acute respiratory failure, congenital heart defect (right-to-left shunt), chronic Eisenmenger syndrome |

| Diminished or Absent Breathing Sounds | COPD, severe asthma, (tension) pneumothorax, pleural effusion, hemothorax |

| Distention of the Neck Veins with Rales in the Lungs | Acutely decompensated congestive heart failure, acute respiratory failure |

| Distention of the Neck Veins with Normal Auscultatory Findings | Pericardial tamponade, acute pulmonary arterial embolism |

| Dizziness, Syncope | Valvular heart disease (e.g., aortic stenosis), hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy, marked anemia, anxiety disorder, hyperventilation |

| Exhaustion, Generalized Weakness, Exercise Intolerance, Muscle Weakness | Anemia, collagenoses, malignancy (e.g., lung cancer), neuromuscular disease |

| Fever | Pulmonary infection (e.g., pneumonia, acute bronchitis), exogenous allergic alveolitis, thyrotoxicosis |

| Heart Murmur | Cardiac valvular disease |

| Hemodynamic Dysfunction – Hypertensive | Hypertensive crisis, panic attack, acute coronary syndrome |

| Hemodynamic Dysfunction – Hypotensive | Forward heart failure, metabolic disturbance, sepsis, pulmonary arterial embolism |

| Hemoptysis | Lung cancer, pulmonary embolism, bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, tuberculosis |

| Hepatojugular Reflux | Acutely decompensated congestive heart failure |

| Hoarseness | Glottis or trachea disease, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy |

| Hyperventilation | Acidosis, sepsis, salicylate poisoning, psychogenic (including anxiety) |

| Impairment of Consciousness | Psychogenic hyperventilation, brain disease, metabolic disturbance, pneumonia |

| Orthopnea | Acute congestive heart failure, toxic pulmonary edema |

| Pain on Respiration | Pneumothorax, pleuritis/pleuropneumonia, pulmonary embolism |

| Pain Independent of Respiration | Myocardial infarction, aortic aneurysm, Roemheld syndrome, renal or biliary colic, acute gastritis |

| Pallor | Marked anemia |

| Paradoxical Pulse | Right-heart failure, pulmonary arterial embolism, cardiogenic shock, pericardial tamponade, asthma exacerbation |

| Peripheral Edema | Congestive heart failure |

| Platypnea | Hepatopulmonary syndrome, intrapulmonary shunting |

| Rales | Pneumonia, acutely decompensated congestive heart failure, acute respiratory failure |

| Stridor – Inspiratory | Croup, foreign body, bacterial tracheitis |

| Stridor – Expiratory/Combined | Foreign body, epiglottitis, angioedema |

| Urticaria | Angioedema |

| Use of Auxiliary Muscles of Respiration | Acute respiratory failure, severe COPD, severe asthma |

| Vegetative Symptoms (Trembling, Cold Sweat, etc.) | Respiratory failure, anxiety disorder, acute myocardial infarction |

| Wheezes | Bronchial asthma exacerbation, COPD, acutely decompensated congestive heart failure, foreign body |

A more detailed symptom characterization aids in differential diagnosis. Several factors are considered:

- Temporal Aspects:

- Acute onset vs. chronic (present for >4 weeks) vs. acute worsening of chronic symptoms

- Intermittent vs. persistent

- Episodic (attacks)

- Situational Aspects:

- At rest

- On exertion

- With emotional stress

- Body position-dependent

- Exposure-dependent

- Pathogenetic Aspects:

- Respiratory system issues (central breathing control, airways, gas exchange)

- Cardiovascular system issues

- Combined cardiac and pulmonary causes

- Other causes (anemia, thyroid disease, deconditioning)

- Mental health causes

The presence of multiple underlying conditions, especially in elderly and multimorbid patients, can complicate the diagnosis and treatment of dyspnea.

Dyspnea: A Common Symptom

Dyspnea is a frequently reported symptom, affecting 7% of patients in hospital emergency rooms and up to 60% in outpatient pulmonology practices.

Illustrative Case Study—Continuation I

Continuing with the 64-year-old patient, her condition is identified as an acute exacerbation of chronic dyspnea. She has a history of hypertension, managed with medication, with stable home systolic blood pressure readings between 135 and 150 mmHg. She is overweight (BMI 30.1 kg/m²) and a smoker (35 pack-years), with no other known cardiovascular risk factors. She denies productive cough or sputum production.

Initial evaluation in primary care includes history and physical exam, basic laboratory tests (complete blood count, thyroid function tests, D-dimer), ECG, and ultrasound if indicated (e.g., to rule out pleural effusion). Pulmonary function tests are considered if lung disease is suspected. Further management (specialist referral, hospitalization) depends on the suspected diagnosis and severity.

Differential Diagnosis: Key Criteria

The differential diagnosis of dyspnea relies on three main criteria:

- Temporal course

- Situational aspects

- Causative factors

Acute Dyspnea

Acute dyspnea can signal life-threatening conditions. Alarm symptoms include confusion, new-onset cyanosis, dyspnea affecting speech, and inadequate respiratory effort or exhaustion. Immediate assessment of life-threatening potential is crucial. Vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation) are essential for rapid decisions on management, including intensive care or assisted ventilation. Respiratory rate is a key indicator; elevated rates on admission are linked to poorer outcomes (ICU admission, higher mortality) and are part of emergency and intensive care scoring systems (e.g., Emergency Severity Index, APACHE II).

Misdiagnosis of acute dyspnea can prolong hospitalization and increase mortality. Patients experiencing sudden dyspnea often feel severely threatened, and emotional factors like panic and anxiety can intensify their distress.

Past medical history and accompanying symptoms (Table 2, eTable 1) provide further clues to the underlying cause of acute dyspnea. Common causes are listed in eTable 2.

Table 2. Symptoms and Signs Accompanying Dyspnea: Differential Diagnostic Significance*.

| Additional Symptoms and Signs | Differential Diagnostic Considerations |

|---|---|

| Diminished or Absent Breathing Sounds | COPD, severe asthma, (tension) pneumothorax, pleural effusion, hemothorax |

| Distention of the Neck Veins with Rales in the Lungs | Acutely Decompensated Heart Failure (ADHF), Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) |

| Distention of the Neck Veins with Normal Auscultatory Findings | Pericardial tamponade, acute pulmonary arterial embolism |

| Dizziness, Syncope | Valvular heart disease (aortic stenosis), hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy, marked anemia, anxiety disorder, hyperventilation |

| Hemodynamic Dysfunction – Hypertensive | Hypertensive crisis, panic attack, acute coronary syndrome |

| Hemodynamic Dysfunction – Hypotensive | Forward heart failure, metabolic disturbance, sepsis, pulmonary arterial embolism |

| Hemoptysis | Lung cancer, pulmonary embolism, bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, tuberculosis |

| Hyperventilation | Acidosis, sepsis, salicylate poisoning, psychogenic (including anxiety) |

| Impairment of Consciousness | Psychogenic hyperventilation, cerebral or metabolic disturbance, pneumonia |

| Orthopnea | Acute congestive heart failure, toxic pulmonary edema |

| Pain on Respiration | Pneumothorax, pleuritis/pleuropneumonia, pulmonary embolism |

| Pain Independent of Respiration | Myocardial infarction, aortic aneurysm, Roemheld syndrome, renal or biliary colic, acute gastritis |

| Pallor | Marked anemia |

| Paradoxical Pulse | Right-heart failure, pulmonary arterial embolism, cardiogenic shock, pericardial tamponade, asthma exacerbation |

| Peripheral Edema | Congestive heart failure |

| Rales | ADHF, ARDS, pneumonia |

| Use of Auxiliary Muscles of Respiration | Respiratory failure/ARDS, severe COPD, severe asthma |

| Wheezes | Asthma exacerbation, COPD, ADHF, foreign body |

*modified from (3, e4– e6), ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ADHF, acutely decompensated heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

The Role of Biomarkers in Dyspnea Diagnosis

ECG is useful for detecting acute myocardial infarction or cardiac arrhythmia. Chest X-ray can identify pulmonary congestion, pneumothorax, or pneumonia. Biomarkers in blood tests are also crucial in the differential diagnosis of acute dyspnea.

Natriuretic Peptides

Acute Dyspnea: A Potential Emergency

Acute onset dyspnea can be a sign of a life-threatening condition, necessitating urgent diagnostic evaluation.

Natriuretic peptides, specifically brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), are valuable for ruling out clinically significant congestive heart failure. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend specific threshold values for BNP and NT-proBNP to exclude heart failure. It is important to note that these thresholds are lower for patients with symptomatic chronic congestive heart failure.

Troponins

When acute coronary syndrome is suspected as the cause of dyspnea, serial cardiac troponin (troponin I or T) measurements are helpful. Elevated troponin levels can effectively rule out acute myocardial ischemia with high certainty. The specific threshold for a positive test depends on the assay used. Repeated troponin measurements have a positive predictive value of 75% to 80% for acute myocardial ischemia.

D-dimers

D-dimers, fibrin degradation products, are elevated after thrombotic events. They have a high negative predictive value for pulmonary embolism diagnosis but are not suitable as a general screening test due to low specificity. Before ordering D-dimer tests, the probability of pulmonary embolism should be assessed using risk scores like the Geneva or Wells Score (eTable 3). In cases of low (or sometimes intermediate) pulmonary embolism likelihood, a normal D-dimer level effectively excludes pulmonary embolism. However, a high Wells Score, indicating high likelihood, necessitates imaging studies. Current guidelines emphasize age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds (age × 10 µg/L for patients over 50) to improve test specificity while maintaining high sensitivity (>97%).

eTable 3. Wells Score for Pulmonary Embolism Probability (Modified from [19, e7]).

| Original Version | Simplified Version |

|---|---|

| Prior pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis (1.5 points) | 1 point |

| Heart rate > 100/min (1.5 points) | 1 point |

| Surgery or immobilization in the last 4 weeks (1.5 points) | 1 point |

| Hemoptysis (1 point) | 1 point |

| Active malignant disease (1 point) | 1 point |

| Clinical evidence of deep venous thrombosis (3 points) | 1 point |

| Alternative diagnosis less likely than pulmonary embolism (3 points) | 1 point |

| 3-level classification | ∑ |

| Low probability (3.6% [2.0–5.9%]) | 0–1 |

| Intermediate probability (20.5% [17.0–24.1%]) | 2–6 |

| High probability (66.7% [54.3–77.6%] | ≥ 7 |

| 2-level classification | ∑ |

| Pulmonary embolism unlikely | 0–4 |

| Pulmonary embolism likely | ≥ 5 |

Emotional Factors in Dyspnea

Emotional factors can exacerbate dyspnea symptoms.

Biomarkers in Dyspnea

Natriuretic peptides (BNP, NT-proBNP) are useful for excluding clinically relevant congestive heart failure.

Cardiac troponins and natriuretic peptides can also be elevated in pulmonary embolism with right-heart strain. Troponin can be elevated in any acute pulmonary disease. Evidence of right-heart strain warrants timely transthoracic echocardiography.

Chronic Dyspnea

Chronic dyspnea often has a limited number of common causes: bronchial asthma, COPD, congestive heart failure, interstitial lung disease, pneumonia, and mental disorders (anxiety, panic, somatization). eTable 2 lists further causes. In older, multimorbid patients, identifying a single cause for chronic dyspnea can be challenging.

eTable 2. Causes of Acute and Chronic Dyspnea (Modified from [24]).

| Acute Dyspnea | Chronic Dyspnea |

|---|---|

| – Angioedema – Anaphylaxis – Pharyngeal infection – Vocal cord dysfunction – Foreign body – Trauma | Head and Neck Region, Upper Airways |

| – Rib fractures – Flail chest – Pneumomediastinum – COPD exacerbation – Asthma attack – Pulmonary embolism – Pneumothorax – Pleural effusion – Pneumonia – Acute respiratory failure – Lung contusion/trauma – Hemorrhage – Lung cancer – Exogenous allergic alveolitis | Chest Wall, Pleura, Lungs |

| – Acute coronary syndrome/myocardial infarction – Acutely decompensated congestive heart failure – Pulmonary edema – High-output failure – Cardiomyopathy – (Tachy-)arrhythmia – Valvular heart disease – Pericardial tamponade | Heart |

| – Stroke – Neuromuscular disease | CNS/Neuromuscular |

| – Organophosphate poisoning – Salicylate poisoning – Carbon monoxide poisoning – Ingestion of other toxic substances – (Diabetic) ketoacidosis | Toxic/Metabolic |

| – Sepsis – Fever – Anemia – Encephalitis – Traumatic brain injury – Acute renal failure – Drugs (beta-blockers, ticagrelor) – Hyperventilation – Anxiety – Intra-abdominal process – Ascites – Pregnancy – Obesity | Other |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; CNS, central nervous system

Common Causes of Chronic Dyspnea

Bronchial asthma, COPD, congestive heart failure, interstitial lung disease, pneumonia, and mental disorders are frequent causes of chronic dyspnea.

Clinical history (risk factors, exposures, prior illnesses) often guides the diagnosis or narrows the differential diagnosis. However, history alone yields a correct diagnosis in only 50-66% of cases. Auscultation and breathing pattern observation provide further diagnostic clues. Rapid, shallow breathing suggests interstitial lung disease, while deep, slow breathing is typical of COPD.

Illustrative Case Study—Continuation II

Diagnostic Difficulties

History alone is sufficient for diagnosis in only half to two-thirds of cases.

Auscultation in our case reveals diminished breath sounds at the lung bases and diffuse, mild rales. A 2/6 systolic heart murmur is noted over the mitral area. Minimal ankle edema is present. ECG shows sinus rhythm (84 bpm) and a positive Sokolow index, indicative of left ventricular hypertrophy.

Further testing is individualized. A proposed diagnostic algorithm for general use has been clinically tested. Some recommend stepwise testing with increasing specificity, guiding subsequent test selection based on results.

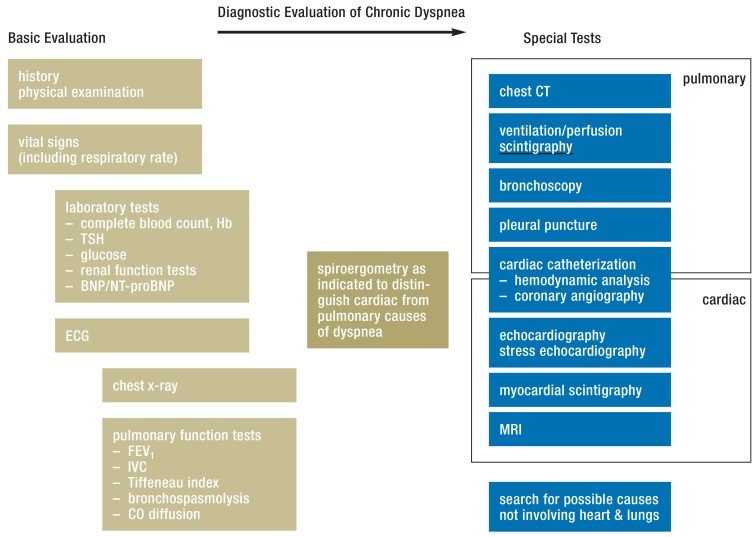

While history and physical exam can suggest a specific diagnosis, if unclear, basic tests can quickly narrow the differential diagnosis and minimize extensive testing (Figure 1). Spiroergometry can differentiate between cardiac and pulmonary causes.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic evaluation of chronic dyspnea, modified from (3, 9, 22, 24). BNP: brain natriuretic peptide, CT: computed tomography, ECG: electrocardiography, FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second, Hb: Hemoglobin IVC: inspiratory vital capacity, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, NT-proBNP: N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide, TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Based on initial findings, appropriate ancillary tests are selected, such as echocardiography, CT, or invasive cardiac catheterization for hemodynamic assessment (Figure 1). Initial test selection should be guided by clinically suspected diagnoses. This selective approach avoids excessive testing but carries risks of diagnostic delay and overlooking multifactorial dyspnea.

Spiroergometry

Spiroergometry is useful for distinguishing cardiac from pulmonary causes of dyspnea.

In some cases, dyspnea etiology requires combined testing. A study of 1969 dyspneic patients without known heart or lung disease aimed to identify parameters most helpful in guiding further testing. Parameters included: ECG (12-lead, abnormalities), CT (coronary artery calcium score, lung volumes with emphysema/interstitial change), echocardiography (ventricular volumes, ejection fraction), spirometry, lab values (fibrinogen, creatinine, CRP, NT-proBNP), BMI, smoking status, blood pressure, diabetes, and symptoms like orthopnea, infections, allergies.

Independent predictors of diagnosis were FEV1, NT-proBNP level, and emphysema percentage on CT.

Specific Diseases Causing Dyspnea

Respiratory System Diseases and Dyspnea

Bronchial Asthma: Chronic airway inflammation leads to variable obstruction, causing frequent dyspnea attacks, often nocturnal. Allergies may be present. Triggers include irritants, allergens, exercise, weather changes, and infections. Auscultation reveals expiratory wheezes. Spirometry shows reduced FEV1 and PEF, which may normalize between episodes. Bronchodilator inhalation improves obstruction and symptoms. Acute dyspnea episodes in asthma are exacerbations, characterized by tachypnea, wheezes, and prolonged expiration.

COPD

COPD is typically characterized by fixed lower airway obstruction. Patients are usually over 40 and are nearly always current or former smokers.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): Chronic bronchitis (cough and sputum for ≥3 months in ≥2 years) is a hallmark. Chronic inflammation leads to lung parenchyma destruction, overinflation, and reduced elastic recoil. COPD is typically characterized by fixed lower airway obstruction, predominantly in patients over 40, almost always smokers or former smokers. Pulmonary function tests and body plethysmography aid diagnosis. Tiffeneau index (FEV1/IVC) is typically <0.7, residual volume may be elevated (overinflation). Low CO diffusion indicates emphysema. Chest X-ray may show flattened diaphragm and rarefied vasculature. Exacerbations requiring hospitalization worsen prognosis. COPD shares risk factors with left heart failure and often coexists.

Pneumonia Severity Assessment

The CRB-65 score assesses pneumonia severity.

Many smokers/ex-smokers have COPD-like symptoms without meeting classic COPD criteria. These patients still experience exacerbations, activity limitations, and airway changes (thickened walls), similar to COPD, and are often treated for airway obstruction despite limited evidence.

Pneumonia

Pleuritic pain, fever, and cough are typical pneumonia symptoms. Examination findings include tachypnea, inspiratory rales, and sometimes bronchial breathing.

Pneumonia: Dyspnea is the main symptom in pneumonia, especially in patients >65 years (≈80%). Typical symptoms include pleuritic pain, fever, and cough. Examination reveals tachypnea, inspiratory rales, and potentially bronchial breathing. Laboratory tests (inflammatory markers, hypoxemia on ABG), chest X-ray, and sometimes chest CT are diagnostically helpful.

The CRB-65 score assesses pneumonia severity (1 point each for: Confusion, Respiratory rate ≥30/min, Blood pressure systolic ≤90 mmHg or diastolic ≤60 mmHg, Age ≥65 years). Scores predict mortality risk and guide hospitalization decisions.

Interstitial Lung Diseases: Patients report chronic dyspnea and nonproductive cough, often smokers. Examination reveals crackling rales at bases and possible digital clubbing/hourglass nails. Pulmonary function testing shows low vital capacity (VC) and total lung capacity (TLC), normal/high Tiffeneau index, and reduced CO diffusion. Differential diagnosis is complex; prognosis and treatment vary. Pulmonology consultation is advisable.

Pulmonary Embolism: Acute pulmonary embolism often presents with acute dyspnea, pleuritic pain, and sometimes hemoptysis. Examination shows shallow breathing and tachycardia. Deep vein thrombosis of the lower limb may be present as the source.

Cardiovascular System Diseases and Dyspnea

Congestive Heart Failure and Dyspnea

Besides dyspnea, patients have fatigue, reduced exercise tolerance, and fluid retention. Both HFrEF and HFpEF are associated with low stroke volume.

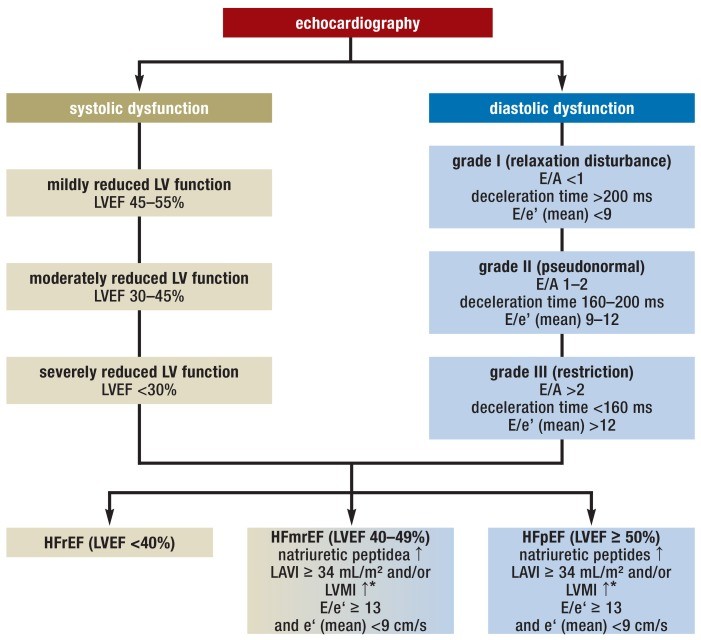

Congestive Heart Failure: Along with dyspnea, symptoms include fatigue, reduced exercise tolerance, and fluid retention. Common causes are advanced coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and valvular heart disease. Heart failure is classified as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF, LVEF <40%) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), both associated with elevated cardiac filling pressures. Heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF, LVEF 40-49% with diastolic dysfunction) is a newly defined category. All types involve reduced stroke volume and cardiac output.

Figure 2.

Echocardiographic criteria for HFrEF, HFpEF, and HFmrEF; modified from (17, 38). LV: left ventricular, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, LAVI: left atrial volume index, LVMI: left ventricular mass index (?*: =115 g/m² for men, = 95 g/m² for women), E: maximal speed of E-wave (mitral inflow), A: maximal speed of A-wave (mitral inflow), e’(mean): mean maximal early diastolic speed (mitral annulus tissue Doppler).

Echocardiography is the primary diagnostic test, assessing systolic and diastolic function using surrogate parameters (Figure 2).

Illustrative Case Study—Continuation III

The findings suggest a cardiac cause for our patient’s dyspnea. Pulmonary function tests reveal mild, non-reversible airway obstruction. Echocardiography shows normal systolic function, grade 2 diastolic dysfunction, and left ventricular hypertrophy. Mild mitral insufficiency is present, correlating with the heart murmur. NT-proBNP is elevated (546 ng/mL) with normal renal function. These findings support a diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) as the primary cause, exacerbated by obesity (BMI 30.1 kg/m²) and smoking-related mild airway obstruction. Mild obstruction on PFTs could also be due to chronic pulmonary congestion, requiring repeat PFTs after decongestion.

Coronary Heart Disease: Dyspnea can be a symptom of coronary stenosis, even as a non-classic symptom, occurring with or without angina, or as the main/sole symptom, especially in diabetics.

Coronary Heart Disease and Dyspnea

Exertional dyspnea can be an atypical sign of coronary heart disease.

History, particularly timing and triggers of dyspnea (stress, cold), can suggest coronary heart disease. Unexplained dyspnea warrants evaluation for coronary artery disease. Assessment includes conventional ergometry and stress tests with imaging (stress echocardiography, myocardial perfusion scintigraphy, stress MRI), followed by cardiac catheterization if suggestive findings are present. Dyspnea is more typical in acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, and cardiogenic shock.

Valvular Heart Disease: Valvular heart disease is another potential cause of dyspnea, especially in the elderly. Common valvular conditions are aortic stenosis and mitral insufficiency. Aortic stenosis typically presents with reduced exercise tolerance, collapse/syncope episodes, dizziness, and angina-like chest pain. Auscultation often reveals a rough systolic murmur loudest parasternally at the second intercostal space, radiating to carotids. Mitral insufficiency presents with heart failure signs. ECG may show atrial fibrillation due to left atrial volume overload. Auscultation reveals a holosystolic murmur at the apex, sometimes radiating to the axilla. Echocardiography is the definitive diagnostic test.

Fundamental Consideration in Dyspnea Evaluation

Heart and lung diseases frequently coexist. When a cause of dyspnea is found in one system, the search should continue for additional causes in the other, given high comorbidity.

Dyspnea Due to Non-Respiratory/Cardiovascular Diseases

The WHO defines anemia as Hb <8.06 mmol/L (13 g/dL) in men or <7.44 mmol/L (12 g/dL) in women. There is no clear Hb threshold for dyspnea in anemia, but evaluation is needed, especially if Hb is <11 g/dL or unexplainedly decreased.

Valvular Heart Disease

Aortic stenosis and mitral insufficiency are common valvular causes of dyspnea.

ENT diseases affecting airways can cause dyspnea. Upper airway issues primarily present with stridor (expiratory in bronchopulmonary compromise, inspiratory in supraglottic, biphasic at/below glottis). Dyspnea occurs with ~30% tidal volume reduction. Causes include congenital malformations, infections, trauma, neoplasia, and neurogenic disturbances.

Neuromuscular diseases (muscular dystrophy, myasthenia, ALS, Guillain-Barré) can cause dyspnea, typically with other neurological manifestations.

Mental illnesses (anxiety, panic, somatization, functional complaints) are diagnoses of exclusion after somatic workup. Dyspnea improvement with distraction/exercise may suggest such disorders.

Iatrogenic (drug-induced) dyspnea should be considered. Non-selective beta-blockers can cause bronchospasm via β2-blockade. NSAIDs (COX-1 inhibitors) increase leukotriene production, causing bronchoconstriction. High-dose aspirin can also induce dyspnea via central receptors. Ticagrelor-induced dyspnea is rare but possible, likely adenosine receptor-mediated.

Drugs Causing Dyspnea

- Non-selective beta-blockers

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Platelet aggregation inhibitors

Table 1. Common Causes of Dyspnea Across Healthcare Settings*.

| Rescue Service | Emergency Room | General Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Heart failure (15–16%) | COPD (16.5%) | Acute bronchitis (24.7%) |

| Pneumonia (10–18%) | Heart failure (16.1%) | Acute upper respiratory infection (9.7%) |

| COPD (13%) | Pneumonia (8.8%) | Other airway infection (6.5%) |

| Bronchial asthma (5–6%) | Myocardial infarction (5.3%) | Bronchial asthma (5.4%) |

| Acute coronary syndrome (3–4%) | Atrial fibrillation/flutter (4.9%) | COPD (5.4%) |

| Pulmonary embolism (2%) | Malignant tumor (3.3%) | Heart failure (5.4%) |

| Lung cancer (1–2%) | Pulmonary embolism (3.3%) | Hypertension (4.3%) |

*modified from (6, 8, e3); COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Conclusion

Dyspnea is a complex symptom with a broad differential diagnosis. A systematic approach, considering temporal factors, situational context, and potential underlying causes across respiratory, cardiovascular, and other systems, is crucial. Utilizing biomarkers and appropriate diagnostic testing, guided by clinical suspicion, is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management, ultimately improving patient outcomes and reducing the burden of this common and distressing symptom.