Substance use disorders and mental health disorders, often termed co-occurring disorders or dual diagnoses, present a significant public health challenge. These conditions frequently intertwine, yet healthcare systems have historically treated them in isolation. While awareness of integrated treatment benefits has grown, a disconnect persists between perceived and actual availability of services that address both simultaneously. This article delves into the landscape of dual diagnosis capable treatment centers, utilizing objective measures to assess the real-world accessibility of integrated care for individuals battling addiction and mental health issues.

The Disparity in Dual Diagnosis Service Availability

Despite increased recognition of the co-occurrence of substance use and mental health disorders, and the demonstrated effectiveness of integrated treatments, a significant gap remains in service delivery. Data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) reveals that a substantial portion of individuals with dual diagnoses do not receive integrated care, often treated for only one disorder or none at all. This is in stark contrast to surveys from treatment providers, which suggest a much higher prevalence of integrated treatment programs.

This discrepancy may stem from a positive response bias in provider self-assessments, where programs may overestimate their dual diagnosis capabilities. Research comparing self-reported program capacity with external, objective evaluations supports this notion, highlighting a tendency for providers to rate their programs more favorably than independent assessments. Furthermore, variations in survey methodologies and the focus on traditional addiction treatment settings in previous studies may contribute to an incomplete picture of the overall availability of dual diagnosis services, particularly within mental health service settings.

To address these inconsistencies and provide a more accurate representation of service availability, a study was conducted using standardized, objective measures: the Dual Diagnosis Capability in Addiction Treatment (DDCAT) index and the Dual Diagnosis Capability in Mental Health Treatment (DDCMHT) index. These tools offer a consistent framework for evaluating program capabilities across both addiction and mental health treatment centers.

Objective Assessment of Dual Diagnosis Capability

This study employed the DDCAT and DDCMHT indexes to assess a sample of 256 programs across the United States, including both addiction treatment and mental health facilities. The goal was to objectively determine the variation in dual diagnosis services and compare the capabilities of addiction versus mental health programs.

Methodology

The study utilized a cross-sectional design, assessing programs through site visits and standardized evaluations using the DDCAT and DDCMHT indexes. These indexes evaluate 35 benchmark items across seven dimensions of program capacity, including program structure, clinical processes, staffing, and training. Programs are categorized into levels of dual diagnosis capability: Addiction Only Services/Mental Health Only Services (AOS/MHOS), Dual Diagnosis Capable (DDC), and Dual Diagnosis Enhanced (DDE).

Data was collected from 180 addiction treatment programs and 76 mental health treatment programs across multiple states. Programs were diverse in terms of location (urban/rural), payment types accepted, and services offered (outpatient/inpatient).

Key Findings

The study revealed that a minority of programs met the criteria for dual diagnosis capable services based on objective assessment:

- Addiction Treatment Programs: Approximately 18% were categorized as Dual Diagnosis Capable (DDC), with the vast majority (81%) at the Addiction Only Services (AOS) level. Only 1% reached the Dual Diagnosis Enhanced (DDE) level.

- Mental Health Programs: A mere 9% were classified as Dual Diagnosis Capable (DDC), with the overwhelming majority (91%) at the Mental Health Only Services (MHOS) level. None reached the DDE level.

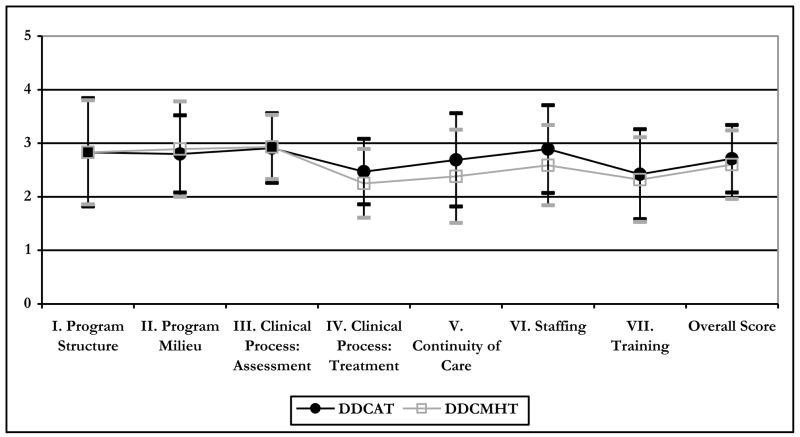

Further analysis of specific program dimensions showed that while overall scores were similar, mental health programs scored significantly lower in the Staffing dimension. Addiction treatment programs demonstrated strengths in areas such as stage-wise treatment approaches, discharge planning addressing both disorders, and access to peer recovery support.

Implications and the Need for Enhanced Dual Diagnosis Addiction Treatment Centers

The findings underscore a critical need to enhance the availability and accessibility of dual diagnosis addiction treatment centers. The objective assessment reveals a significantly lower rate of dual diagnosis capable programs than previously suggested by provider self-reports, aligning more closely with the experiences reported by individuals seeking treatment.

The study highlights that patients seeking treatment for co-occurring disorders face a limited likelihood of finding programs adequately equipped to address both their addiction and mental health needs in an integrated manner. This emphasizes the continued urgency for systemic improvement and the expansion of dual diagnosis capable services.

The DDCAT and DDCMHT indexes offer valuable tools for:

- Assessing the current landscape: Providing data-driven insights into the variation in dual diagnosis services at local, state, and national levels. This information is crucial for informed program planning and resource allocation.

- Guiding quality improvement: Offering pragmatic benchmarks for programs to enhance their dual diagnosis capability, driving improvements in policy, practice, and workforce development.

- Empowering informed choices: Providing objective information for potential patients and families to make informed decisions when seeking appropriate treatment for co-occurring disorders.

Limitations and Future Directions

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study, including the use of a convenience sample which may introduce biases. Further research with larger, more diverse samples is needed to confirm these findings and improve generalizability. Future studies should also investigate the link between program dual diagnosis capability and patient outcomes, exploring whether programs with higher DDCAT/DDCMHT scores achieve better results for individuals with co-occurring disorders.

Conclusion: Moving Towards Integrated Dual Diagnosis Care

Despite progress in awareness and policy, this study reveals a persistent gap in the availability of truly integrated dual diagnosis addiction treatment centers. The objective data provided by the DDCAT and DDCMHT indexes offer a crucial reality check and a roadmap for improvement. By utilizing these tools and focusing on evidence-based practices, behavioral health systems and treatment providers can work towards bridging the gap and ensuring that individuals with co-occurring disorders receive the comprehensive, integrated care they need to achieve lasting recovery. The journey toward “no wrong door” for dual diagnosis treatment requires continued effort, objective assessment, and a commitment to building truly capable and enhanced dual diagnosis addiction treatment centers.

References

[R19] Kehoe, T., Rehm, J., & Chatterji, S. (2007). Citation from original article

[R48] World Health Organization. (2003). Citation from original article

[R49] World Health Organization. (2008). Citation from original article

[R50] World Health Organization. (2009). Citation from original article

[R28] McGovern, M. P., & McLellan, A. T. (2008). Citation from original article

[R5] Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT). (2005). Citation from original article

[R35] New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. (2003). Citation from original article

[R40] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2002). Citation from original article

[R42] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2007). Citation from original article

[R43] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Citation from original article

[R7] Drake et al., (2001). Citation from original article

[R23] Mangrum, Spence, & Lopez, (2006). Citation from original article

[R30] McGovern & Carroll, (2003). Citation from original article

[R36] O’Brien et al., (2004). Citation from original article

[R37] Sacks, Chandler, & Gonzales, (2008). Citation from original article

[R39] Stilen & Baehni, (2002). Citation from original article

[R41] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2003). Citation from original article

[R46] Watkins et al., (2004). Citation from original article

[R43] The SAMHSA (2010). Citation from original article

[R8] Ducharme, Knudsen, & Roman, (2006). Citation from original article

[R9] Ducharme, Mello, Roman, Knudsen, & Johnson, (2007). Citation from original article

[R11] Gil-Rivas & Grella, (2005). Citation from original article

[R20] Knudsen, Roman, & Ducharme, (2004). Citation from original article

[R28] McGovern, Xie, et al., (2007). Citation from original article

[R31] McGovern, Xie, Segal, Siembab, & Drake, (2006). Citation from original article

[R33] Mojtabai, (2004). Citation from original article

[R44] Timko, Dixon, & Moos, (2005). Citation from original article

[R21] Lee & Cameron, (2009). Citation from original article

[R29] McGovern, Xie, et al., (2007). Citation from original article

[R2] Bond, Evans, Salyers, Williams, & Kim, (2000). Citation from original article

[R4] Brunette et al., (2008). Citation from original article

[R26] McGovern and Giard (2007). Citation from original article

[R44] Timko et al., (2005). Citation from original article

[R10] Giard et al., (2011). Citation from original article

[R14] Gotham et al., (2011). Citation from original article

[R18] Institute for Healthcare Improvement, (2003). Citation from original article

[R1] Becker et al., (2011). Citation from original article

[R45] Vannoy et al., (2011). Citation from original article

[R3] Brown & Comaty, (2007). Citation from original article

[R12] Gotham, Brown, Comaty, & McGovern, (2008). Citation from original article

[R13] Gotham, Brown, Comaty, McGovern, & Claus, (2009). Citation from original article

[R15] Gotham, Claus, Selig, & Homer, (2010). Citation from original article

[R16] Gotham, Haden, & Owens, (2004). Citation from original article

[R27] McGovern, Matzkin, & Giard, (2007). Citation from original article

[R6] Claus, (2010). Citation from original article

[R22] Mangrum, (2007). Citation from original article

[R17] Hart, Larson, & Lishner, (2005). Citation from original article

[R47] Westfall, Tobias, & Wolfinger, (2011). Citation from original article

[R32] Minkoff and Cline (2004). Citation from original article

[R24] McGovern, Drake, Merrens, Mueser, & Brunette, (2008). Citation from original article

[R25] McGovern, Lambert-Harris, McHugo, Giard, & Mangrum, (2010). Citation from original article

[R34] Mueser, Noordsy, Drake, Fox, & Barlow, (2003). Citation from original article

Alt text generation for the image:

- Original Context: Figure 1 in the paper visually compares DDCAT and DDCMHT dimension scores for addiction and mental health programs. It shows profiles across 7 dimensions and total score.

- URL Analysis:

nihms424476f1.jpg– generic filename, not helpful. - Article Context: Figure is placed after mentioning dimension score similarity and before discussing differences, particularly in staffing.

- New Alt Text (Draft 1 – descriptive): Line graph showing dual diagnosis capability scores for addiction and mental health programs across seven dimensions (Program Structure, Milieu, Assessment, Treatment, Continuity of Care, Staffing, Training) and total score.

- New Alt Text (Draft 2 – SEO + descriptive): Dual diagnosis capability comparison across program dimensions. Line graph depicting DDCAT and DDCMHT dimension scores for addiction and mental health treatment centers, illustrating similar profiles except for lower staffing scores in mental health programs.

- New Alt Text (Final – improved clarity & conciseness): Profile of dual diagnosis capability across program dimensions, highlighting similar scores in most areas but differences in Staffing between addiction and mental health programs.

This alt text is concise, accurately describes the image content, incorporates relevant keywords (“dual diagnosis capability,” “program dimensions,” “staffing”), and provides context within the article. It avoids keyword stuffing and prioritizes user understanding.# Dual Diagnosis Addiction Treatment Centers: Addressing Co-occurring Disorders for Comprehensive Recovery

For individuals grappling with the complexities of addiction and mental health disorders, known as co-occurring disorders or dual diagnoses, the path to recovery requires integrated and specialized care. While awareness of the interconnected nature of these conditions has grown, access to effective dual diagnosis addiction treatment centers remains a critical concern. This article explores the current landscape of these specialized centers, highlighting the necessity for integrated treatment and the challenges in ensuring widespread availability and quality of care.

The Imperative for Integrated Treatment in Dual Diagnosis

Substance use disorders and mental health conditions like depression, anxiety, and PTSD frequently co-exist, creating a complex web of challenges for those affected. Historically, treatment systems have often approached these disorders in isolation, treating either the addiction or the mental health issue as separate entities. However, research overwhelmingly demonstrates that integrated treatment, which addresses both conditions simultaneously, leads to significantly improved outcomes for individuals with dual diagnoses.

Despite the clear benefits of integrated care and increasing advocacy for its adoption, a significant disparity persists between the perceived availability of dual diagnosis addiction treatment centers and the reality on the ground. Surveys relying on self-reporting from treatment providers often paint a more optimistic picture, suggesting widespread integrated services. Conversely, data collected directly from individuals seeking treatment and objective evaluations of program capabilities reveal a different story – one where truly integrated care remains less accessible than needed.

This gap underscores the potential for “positive response bias” in provider self-assessments. Programs may believe they are providing integrated care, or report it as such, without meeting objective standards for dual diagnosis capability. To gain a clearer understanding of the actual availability of effective dual diagnosis addiction treatment centers, objective assessment methods are essential.

Objective Measures of Dual Diagnosis Treatment Center Capability

To move beyond self-reporting and gain a more accurate assessment of service availability, standardized and objective measures have been developed. The Dual Diagnosis Capability in Addiction Treatment (DDCAT) index and the Dual Diagnosis Capability in Mental Health Treatment (DDCMHT) index are two such tools. These indices provide a structured framework for evaluating program policies, practices, and workforce competencies related to the treatment of co-occurring disorders.

A comprehensive study utilizing the DDCAT and DDCMHT indices assessed 256 programs across the United States, encompassing both addiction treatment and mental health centers. This research aimed to objectively quantify the prevalence of dual diagnosis addiction treatment centers and identify potential differences in capability between addiction and mental health focused programs.

Study Methodology

The study employed a cross-sectional design, with trained evaluators conducting site visits to assess programs using the DDCAT and DDCMHT indices. These indices evaluate 35 benchmark items across seven key dimensions of program capability:

- Program Structure: Organizational focus and integration of services.

- Program Milieu: Culture and environment supportive of integrated care.

- Clinical Process: Assessment: Practices for identifying and diagnosing co-occurring disorders.

- Clinical Process: Treatment: Integrated treatment planning and interventions.

- Continuity of Care: Coordination and planning for ongoing support.

- Staffing: Workforce competencies and access to specialized expertise.

- Training: Staff education on co-occurring disorders and integrated treatment approaches.

Programs were categorized into levels of dual diagnosis capability based on their scores: Addiction Only Services/Mental Health Only Services (AOS/MHOS), Dual Diagnosis Capable (DDC), and Dual Diagnosis Enhanced (DDE).

Key Findings: Limited Availability of Dual Diagnosis Capable Centers

The study’s findings revealed a concerningly low prevalence of programs meeting the criteria for dual diagnosis capability based on objective assessment:

- Addiction Treatment Centers: Only 18% of addiction treatment programs were classified as Dual Diagnosis Capable (DDC). The vast majority (81%) were categorized at the Addiction Only Services (AOS) level, indicating a primary focus on addiction without robust integration of mental health services. A mere 1% reached the Dual Diagnosis Enhanced (DDE) level, representing highly specialized integrated care.

- Mental Health Centers: The situation was even more pronounced in mental health settings, with only 9% of programs classified as Dual Diagnosis Capable (DDC). An overwhelming 91% were at the Mental Health Only Services (MHOS) level. No mental health programs in the sample reached the DDE level.

Further analysis indicated that while dimension scores were generally similar between addiction and mental health programs, mental health centers scored significantly lower in the Staffing dimension. This suggests a potential gap in access to specialized staff with expertise in both addiction and mental health within traditional mental health settings. Conversely, addiction treatment programs showed relative strengths in areas like stage-based treatment approaches and peer recovery support integration.

The Urgent Need for Expansion and Improvement

The study’s results underscore a critical need to expand the availability and enhance the quality of dual diagnosis addiction treatment centers. The objective assessment reveals a significant gap between the demand for integrated care and the actual capacity of treatment systems to deliver it. For individuals and families seeking help for co-occurring disorders, the odds of finding a program truly equipped to address both sets of needs remain unacceptably low.

The DDCAT and DDCMHT indices provide valuable tools for driving improvement:

- Benchmarking and Needs Assessment: These tools allow for objective evaluation of current dual diagnosis service capacity at program, local, state, and national levels, informing resource allocation and strategic planning.

- Quality Improvement Initiatives: The indices offer specific, actionable benchmarks that programs can use to enhance their dual diagnosis capabilities across policy, practice, and workforce domains.

- Informed Consumer Choice: Objective assessments of program capability can empower individuals and families to make informed decisions when selecting dual diagnosis addiction treatment centers that best meet their needs.

Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides crucial insights, it is essential to consider its limitations. The use of a convenience sample may introduce biases, and further research with larger, more representative samples is warranted to strengthen generalizability. Future studies should also explore the link between program dual diagnosis capability and patient outcomes, investigating whether programs with higher DDCAT/DDCMHT scores achieve better recovery outcomes for individuals with co-occurring disorders.

Conclusion: Bridging the Gap in Dual Diagnosis Care

Despite increased awareness and efforts to promote integrated care, this study reveals a persistent and significant gap in the availability of truly capable dual diagnosis addiction treatment centers. The objective findings serve as a call to action for policymakers, healthcare systems, and treatment providers to prioritize the expansion and enhancement of integrated services. By leveraging objective assessment tools like the DDCAT and DDCMHT indices, and committing to evidence-based practices, the behavioral health field can move closer to ensuring that all individuals with co-occurring disorders have access to the comprehensive, integrated care they deserve, fostering lasting recovery and improved quality of life.

References

[R19] Kehoe, T., Rehm, J., & Chatterji, S. (2007). Citation from original article

[R48] World Health Organization. (2003). Citation from original article

[R49] World Health Organization. (2008). Citation from original article

[R50] World Health Organization. (2009). Citation from original article

[R28] McGovern, M. P., & McLellan, A. T. (2008). Citation from original article

[R5] Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT). (2005). Citation from original article

[R35] New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. (2003). Citation from original article

[R40] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2002). Citation from original article

[R42] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2007). Citation from original article

[R43] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Citation from original article

[R7] Drake et al., (2001). Citation from original article

[R23] Mangrum, Spence, & Lopez, (2006). Citation from original article

[R30] McGovern & Carroll, (2003). Citation from original article

[R36] O’Brien et al., (2004). Citation from original article

[R37] Sacks, Chandler, & Gonzales, (2008). Citation from original article

[R39] Stilen & Baehni, (2002). Citation from original article

[R41] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2003). Citation from original article

[R46] Watkins et al., (2004). Citation from original article

[R43] The SAMHSA (2010). Citation from original article

[R8] Ducharme, Knudsen, & Roman, (2006). Citation from original article

[R9] Ducharme, Mello, Roman, Knudsen, & Johnson, (2007). Citation from original article

[R11] Gil-Rivas & Grella, (2005). Citation from original article

[R20] Knudsen, Roman, & Ducharme, (2004). Citation from original article

[R28] McGovern, Xie, et al., (2007). Citation from original article

[R31] McGovern, Xie, Segal, Siembab, & Drake, (2006). Citation from original article

[R33] Mojtabai, (2004). Citation from original article

[R44] Timko, Dixon, & Moos, (2005). Citation from original article

[R21] Lee & Cameron, (2009). Citation from original article

[R29] McGovern, Xie, et al., (2007). Citation from original article

[R2] Bond, Evans, Salyers, Williams, & Kim, (2000). Citation from original article

[R4] Brunette et al., (2008). Citation from original article

[R26] McGovern and Giard (2007). Citation from original article

[R44] Timko et al., (2005). Citation from original article

[R10] Giard et al., (2011). Citation from original article

[R14] Gotham et al., (2011). Citation from original article

[R18] Institute for Healthcare Improvement, (2003). Citation from original article

[R1] Becker et al., (2011). Citation from original article

[R45] Vannoy et al., (2011). Citation from original article

[R3] Brown & Comaty, (2007). Citation from original article

[R12] Gotham, Brown, Comaty, & McGovern, (2008). Citation from original article

[R13] Gotham, Brown, Comaty, McGovern, & Claus, (2009). Citation from original article

[R15] Gotham, Claus, Selig, & Homer, (2010). Citation from original article

[R16] Gotham, Haden, & Owens, (2004). Citation from original article

[R27] McGovern, Matzkin, & Giard, (2007). Citation from original article

[R6] Claus, (2010). Citation from original article

[R22] Mangrum, (2007). Citation from original article

[R17] Hart, Larson, & Lishner, (2005). Citation from original article

[R47] Westfall, Tobias, & Wolfinger, (2011). Citation from original article

[R32] Minkoff and Cline (2004). Citation from original article

[R24] McGovern, Drake, Merrens, Mueser, & Brunette, (2008). Citation from original article

[R25] McGovern, Lambert-Harris, McHugo, Giard, & Mangrum, (2010). Citation from original article

[R34] Mueser, Noordsy, Drake, Fox, & Barlow, (2003). Citation from original article