The intersection of substance use disorders and mental health conditions, often termed co-occurring disorders or dual diagnosis, presents a significant public health challenge. Individuals facing these combined challenges require specialized and integrated care, yet the availability and accessibility of such services remain inconsistent. This article delves into the critical issue of Dual Diagnosis Treatment Programs, drawing upon research that objectively assesses the capacity of addiction treatment and mental health programs to effectively address co-occurring disorders. By utilizing standardized measures, this analysis sheds light on the current landscape of dual diagnosis care and underscores the urgent need for enhanced and truly integrated treatment approaches.

Historically, healthcare systems have often treated substance use and mental health disorders in isolation, despite their frequent co-occurrence. This fragmented approach has proven inadequate for individuals needing comprehensive care. Over the past decade, there has been a growing recognition of the importance of integrated treatment models, leading to policy changes and increased awareness. However, recent studies reveal a persistent gap between the recognized need for integrated services and the reality of available treatment. Many individuals with co-occurring disorders still receive disjointed care, addressing only one aspect of their complex needs. This is particularly concerning given the overwhelming evidence that integrated treatment programs lead to significantly better outcomes for patients. Research consistently demonstrates that when substance use and mental health disorders are treated concurrently and in a coordinated manner, individuals experience improved recovery rates and overall well-being.

Despite the clear benefits of integrated approaches, there is a notable discrepancy in how the availability of dual diagnosis treatment programs is perceived. Surveys of treatment providers often suggest a higher prevalence of integrated services than what is reported by individuals seeking treatment within communities. This difference highlights the potential for overestimation in self-reported program capabilities and underscores the importance of objective assessments. This article will explore the findings of a comprehensive study that employed objective measures – the Dual Diagnosis Capability in Addiction Treatment (DDCAT) and Dual Diagnosis Capability in Mental Health Treatment (DDCMHT) indexes – to evaluate program capacity across the United States. By examining the results of this research, we aim to provide a clearer understanding of the actual availability of dual diagnosis treatment programs and identify areas for improvement in bridging the gap between service provision and patient needs.

Why the Discrepancy in Reported Dual Diagnosis Services?

The variance between provider self-assessments and external evaluations of integrated service capacity points to a critical issue in accurately gauging the availability of dual diagnosis treatment programs. Research comparing self-reported program capabilities with objective assessments has revealed a consistent pattern: programs tend to overestimate their capacity to deliver integrated services when self-assessing. This phenomenon mirrors findings in other healthcare fields, where self-reported adherence to evidence-based practices often differs significantly from independent, objective evaluations.

A graph comparing self-assessment versus external assessment of program level integrated services capacity.

A graph comparing self-assessment versus external assessment of program level integrated services capacity.

Image alt text: Bar graph illustrating the difference between self-assessment and external assessment scores for integrated service capacity in dual diagnosis programs.

In the context of dual diagnosis capability, studies utilizing the Dual Diagnosis Capability in Addiction Treatment (DDCAT) index have quantified this discrepancy. For example, one study found an average 2-point difference on a 5-point scale between program directors’ ratings and independent evaluators’ assessments of program capacity. Similarly, another study using the DDCAT revealed that while 75% of program leaders categorized their programs as Dual Diagnosis Capable (DDC), objective evaluators rated only 25% as meeting this criterion. These findings suggest that a significant portion of the perceived availability of dual diagnosis treatment programs may be attributed to positive response bias in provider self-reporting. This highlights the necessity for relying on objective, standardized measures to obtain a more accurate understanding of the true landscape of dual diagnosis services. Furthermore, variations in how providers are questioned about their services may also contribute to the discrepancy, emphasizing the importance of consistent and standardized assessment methodologies.

It is also important to note that much of the existing data on dual diagnosis services has focused primarily on traditional community addiction treatment providers. Information regarding the availability of integrated services within traditional mental health service settings has been comparatively limited. This gap in data further complicates the understanding of the overall availability of dual diagnosis treatment programs and underscores the need for research that encompasses both addiction and mental health service sectors.

Assessing Dual Diagnosis Capability: The DDCAT and DDCMHT Indexes

To address the need for objective and comparable measures of dual diagnosis capability, researchers developed the Dual Diagnosis Capability in Addiction Treatment (DDCAT) and Dual Diagnosis Capability in Mental Health Treatment (DDCMHT) indexes. These instruments provide standardized frameworks for evaluating the capacity of both addiction and mental health treatment programs to effectively serve individuals with co-occurring disorders. Both the DDCAT and DDCMHT indexes are structured similarly, employing the same rating scale and encompassing the same number of items. This parallel design allows for direct comparisons of dual diagnosis capability across different types of treatment programs.

The DDCAT and DDCMHT indexes utilize a comprehensive assessment approach that involves on-site visits to treatment programs. During these visits, trained evaluators gather data through ethnographic observation, interviews with staff and patients, and reviews of program documentation. The assessment focuses on 35 benchmark items spanning seven key dimensions of program functioning:

- Program Structure: Examines the organizational framework and policies supporting integrated care.

- Program Milieu: Assesses the environment and culture of the program in relation to co-occurring disorders.

- Clinical Process: Assessment: Evaluates the program’s methods for identifying and assessing co-occurring disorders.

- Clinical Process: Treatment: Analyzes the program’s therapeutic approaches for addressing co-occurring disorders.

- Continuity of Care: Examines the program’s strategies for ensuring ongoing and coordinated care.

- Staffing: Assesses the qualifications, training, and integration of program staff.

- Training: Evaluates the program’s provision of training on co-occurring disorders for staff.

Each benchmark item is scored using a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (representing Addiction Only Services (AOS) or Mental Health Only Services (MHOS)) to 5 (representing Dual Diagnosis Enhanced (DDE)). Intermediate scores of 2 and 4 are used to capture nuances between these categories. Based on the cumulative scores across the 35 items, programs are categorized into one of three levels of dual diagnosis capability:

- AOS/MHOS Level: Indicates minimal capacity to address co-occurring disorders, primarily focused on single-disorder treatment.

- DDC Level: Signifies a program that is Dual Diagnosis Capable, with the foundational elements for integrated care in place.

- DDE Level: Represents a Dual Diagnosis Enhanced program, demonstrating a high degree of integration and specialized expertise in treating co-occurring disorders.

The DDCAT and DDCMHT indexes have undergone rigorous psychometric testing, demonstrating strong reliability and validity. These measures provide a robust and objective method for evaluating and comparing the dual diagnosis capability of treatment programs, contributing valuable data for program planning, quality improvement, and resource allocation.

National Assessment of Dual Diagnosis Program Capability: Key Findings

A recent national study utilized the DDCAT and DDCMHT indexes to assess a sample of 256 treatment programs across the United States, comprising 180 addiction treatment programs and 76 mental health programs. The findings of this study offer a critical insight into the current state of dual diagnosis service availability.

The assessment revealed a significant disparity between the ideal of integrated care and the reality of program capabilities. The vast majority of programs assessed were categorized at the lowest level of dual diagnosis capability:

- Addiction Treatment Programs: 81% were classified as Addiction Only Services (AOS) level. Only 18% were categorized as Dual Diagnosis Capable (DDC), and a mere 1% reached the Dual Diagnosis Enhanced (DDE) level.

- Mental Health Programs: 91% were classified as Mental Health Only Services (MHOS) level. Only 9% were categorized as DDC, and none reached the DDE level.

Image alt text: Table displaying the percentage of addiction and mental health treatment programs categorized as AOS/MHOS, DDC, and DDE based on DDCAT and DDCMHT assessments.

These findings indicate that, across the programs sampled, individuals seeking care for co-occurring disorders face a limited probability of accessing truly integrated treatment. Specifically, the study suggests that patients and families have approximately a 1 in 10 to 2 in 10 chance of finding programs adequately equipped to address both their substance use and mental health needs concurrently. This stark reality underscores the persistent need for systemic improvements in the provision of dual diagnosis treatment programs.

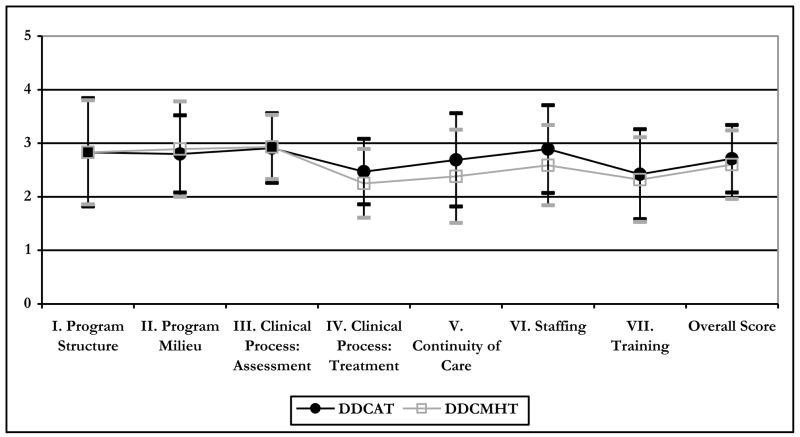

Further analysis of the DDCAT and DDCMHT dimension scores revealed similarities across most domains between addiction and mental health programs. However, mental health programs scored significantly lower in the Staffing dimension, indicating potential challenges related to workforce capacity and expertise in addressing co-occurring disorders.

Image alt text: Line graph comparing average dimension scores and total scores for addiction treatment and mental health treatment programs on the DDCAT and DDCMHT indexes.

Examining individual benchmark items within the dimensions highlighted specific areas of divergence between addiction and mental health programs. Notably, addiction treatment programs demonstrated significantly higher scores in several key areas:

- Clinical Process: Assessment: Addiction programs were more likely to assess patients’ stage of motivation to address both substance use and mental health concerns.

- Clinical Process: Treatment: Addiction programs were more likely to adjust treatment approaches based on patients’ stage of motivation.

- Continuity of Care: Addiction programs exhibited stronger discharge planning for both substance use and psychiatric problems and placed a greater focus on recovery issues for both types of disorders.

- Staffing: Addiction programs demonstrated better access to integrated supervision or consultation and were more likely to provide access to peer recovery support persons.

These differences suggest that addiction treatment programs, in certain aspects of clinical process and continuity of care, may be further along in integrating dual diagnosis approaches compared to mental health programs. However, the overall low prevalence of DDC and DDE level programs across both sectors emphasizes the widespread need for improvement in dual diagnosis treatment capacity.

Implications and the Path Forward for Dual Diagnosis Treatment

The findings of this national assessment carry significant implications for the behavioral health field and underscore the urgent need to enhance the availability and quality of dual diagnosis treatment programs. Despite increasing awareness and policy efforts, the study reveals a persistent gap between the recognized need for integrated care and the actual capacity of treatment programs to deliver such services.

The objective data provided by the DDCAT and DDCMHT indexes offer several key benefits:

- Data-Driven Needs Assessment: These measures provide a robust methodology for assessing the current landscape of dual diagnosis services at national, state, and local levels. This data can inform program planning, resource allocation, and quality improvement initiatives.

- Objective Benchmarks for Improvement: The DDCAT and DDCMHT provide concrete, measurable benchmarks for programs seeking to enhance their dual diagnosis capability. These benchmarks can guide policy development, practice implementation, and workforce training efforts.

- Measuring Progress Over Time: The standardized nature of these measures allows for tracking changes in program capability over time, enabling the evaluation of quality improvement initiatives and systemic changes.

- Informed Consumer Choice: Objective assessments of program capability can provide valuable information for individuals and families seeking dual diagnosis treatment, empowering them to make informed choices about their care.

Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of utilizing the DDCAT and DDCMHT indexes to drive quality improvement initiatives. Learning collaboratives employing these measures have shown significant increases in dual diagnosis capability within both addiction treatment and mental health programs over time. These successes highlight the practical utility of these tools in fostering real-world improvements in service delivery.

While this study provides valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. The sample of programs, while diverse, was a convenience sample and may not fully represent the entire spectrum of treatment programs nationwide. Further research with larger and more systematically selected samples is needed to confirm these findings and enhance generalizability. Additionally, future research should focus on linking program-level capability, as measured by the DDCAT and DDCMHT, with patient-level outcomes. Understanding the direct impact of enhanced dual diagnosis capability on treatment effectiveness and patient recovery is crucial for demonstrating the value and necessity of investing in integrated care models.

Conclusion: Bridging the Gap for Effective Dual Diagnosis Care

Despite decades of effort to promote integrated services for individuals with co-occurring disorders, this study’s findings reveal that substantial improvements are still needed. The limited availability of Dual Diagnosis Capable and Dual Diagnosis Enhanced programs underscores a significant gap in the behavioral health system. The DDCAT and DDCMHT indexes offer practical and objective tools to guide and measure progress in bridging this gap. By embracing these benchmarks and prioritizing the implementation of evidence-based practices, community mental health and addiction treatment programs can enhance their capacity to provide truly integrated care. This, in turn, will significantly improve the lives of individuals navigating the complexities of co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders, offering them a greater chance at achieving lasting recovery and well-being.

References

[References list from original article, formatted in markdown as a numbered list]

- Kehoe, T., Rehm, J., & Chatterji, S. (2007). [Rest of citation]

- World Health Organization. (2003). [Rest of citation]

- World Health Organization. (2008). [Rest of citation]

- World Health Organization. (2009). [Rest of citation]

- McGovern, M. P., & McLellan, A. T. (2008). [Rest of citation]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT). (2005). [Rest of citation]

- New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. (2003). [Rest of citation]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2002). [Rest of citation]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2007). [Rest of citation]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). [Rest of citation]

- Drake, R. E., et al. (2001). [Rest of citation]

- Mangrum, L. F., Spence, R. T., & Lopez, M. I. (2006). [Rest of citation]

- McGovern, M. P., & Carroll, K. M. (2003). [Rest of citation]

- O’Brien, C. P., et al. (2004). [Rest of citation]

- Sacks, S., Chandler, R. K., & Gonzales, J. J. (2008). [Rest of citation]

- Stilen, H. M., & Baehni, B. L. (2002). [Rest of citation]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2003). [Rest of citation]

- Watkins, K. E., et al. (2004). [Rest of citation]

- The SAMHSA. (2010). [Rest of citation]

- Ducharme, L. J., Knudsen, H. K., & Roman, P. M. (2006). [Rest of citation]

- Ducharme, L. J., Mello, P. F., Roman, P. M., Knudsen, H. K., & Johnson, J. A. (2007). [Rest of citation]

- Gil-Rivas, V., & Grella, C. E. (2005). [Rest of citation]

- Knudsen, H. K., Roman, P. M., & Ducharme, L. J. (2004). [Rest of citation]

- McGovern, M. P., Xie, H., et al. (2007). [Rest of citation]

- McGovern, M. P., Xie, H., Segal, S. R., Siembab, L. A., & Drake, R. E. (2006). [Rest of citation]

- Mojtabai, R. (2004). [Rest of citation]

- Timko, C., Dixon, L. B., & Moos, R. H. (2005). [Rest of citation]

- Lee, N. K., & Cameron, J. (2009). [Rest of citation]

- McGovern, M. P., Xie, et al. (2007). [Rest of citation]

- Bond, G. R., Evans, L., Salyers, M. P., Williams, J., & Kim, H. S. (2000). [Rest of citation]

- Brunette, M. F., et al. (2008). [Rest of citation]

- McGovern, M. P., & Giard, J. A. (2007). [Rest of citation]

- Giard, J. A., et al. (2011). [Rest of citation]

- Gotham, H. J., et al. (2011). [Rest of citation]

- Gotham, H., Brown, C., Comaty, S. J., & McGovern, M. P. (2008). [Rest of citation]

- Gotham, H. J., Brown, C., Comaty, S. J., McGovern, M. P., & Claus, R. E. (2009). [Rest of citation]

- Gotham, H. J., Claus, R. E., Selig, N. A., & Homer, J. (2010). [Rest of citation]

- Gotham, H., Haden, N., & Owens, J. (2004). [Rest of citation]

- Brown, C., & Comaty, S. J. (2007). [Rest of citation]

- McGovern, M. P., Matzkin, R. E., & Giard, J. A. (2007). [Rest of citation]

- Claus, R. E. (2010). [Rest of citation]

- Mangrum, L. F. (2007). [Rest of citation]

- Hart, L. G., Larson, E. H., & Lishner, D. M. (2005). [Rest of citation]

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (2003). [Rest of citation]

- McGovern, M. P., Drake, R. E., Merrens, M. R., Mueser, K. T., & Brunette, M. F. (2008). [Rest of citation]

- McGovern, M. P., Lambert-Harris, C., McHugo, G. J., Giard, J. A., & Mangrum, L. F. (2010). [Rest of citation]

- Minkoff, K., & Cline, N. (2004). [Rest of citation]

- Mueser, K. T., Noordsy, D. L., Drake, R. E., Fox, L., & Barlow, D. H. (2003). [Rest of citation]

- Westfall, P. H., Tobias, R. D., & Wolfinger, R. D. (2011). [Rest of citation]

- Becker, D. R., et al. (2011). [Rest of citation]

- Vannoy, S. D., et al. (2011). [Rest of citation]

- SPSS. (2008). [Rest of citation]