Introduction

Early diagnosis of breast cancer is universally recognized as critical for improving survival rates and patient outcomes. When breast cancer is detected and treated in its nascent stages, the likelihood of successful treatment and long-term survival is significantly enhanced. However, numerous obstacles impede women worldwide from accessing timely early detection services. These barriers, often interwoven and complex, encompass social, economic, geographical, and systemic factors that limit access to affordable and effective breast health care. Understanding the Early Diagnosis Cost Of Care Cancer is crucial for developing effective strategies to overcome these barriers and improve global breast cancer outcomes.

The World Health Organization (WHO) distinguishes between two key approaches to early cancer detection: early diagnosis and screening. Early diagnosis focuses on recognizing symptomatic cancer at an early stage after a patient presents with symptoms. Screening, conversely, aims to identify asymptomatic disease in a seemingly healthy population. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), a disproportionate number of women are diagnosed with advanced-stage breast cancer. In these regions, prioritizing early diagnosis initiatives is paramount, serving as a fundamental step before implementing population-based screening programs. Early diagnosis benefits all breast cancer patients, whereas even the most advanced screening programs detect less than half of all breast cancers. Therefore, until the necessary infrastructure and organizational frameworks for screening are robustly established, focusing on enhancing early diagnosis efforts should take precedence. Health policymakers, planners, and stakeholders, including clinicians, educators, community leaders, and patient advocates, must comprehend both the health system prerequisites and the overall cost of care associated with these early detection strategies to facilitate informed investments, planning, and policy formulation.

Figure 1. Distinguishing Screening from Early Diagnosis Based on Symptom Onset

Alt text: Diagram illustrating the differentiation between early diagnosis and screening for cancer detection, based on the presence or absence of symptoms, as defined by the World Health Organization’s 2017 guidelines on cancer early diagnosis.

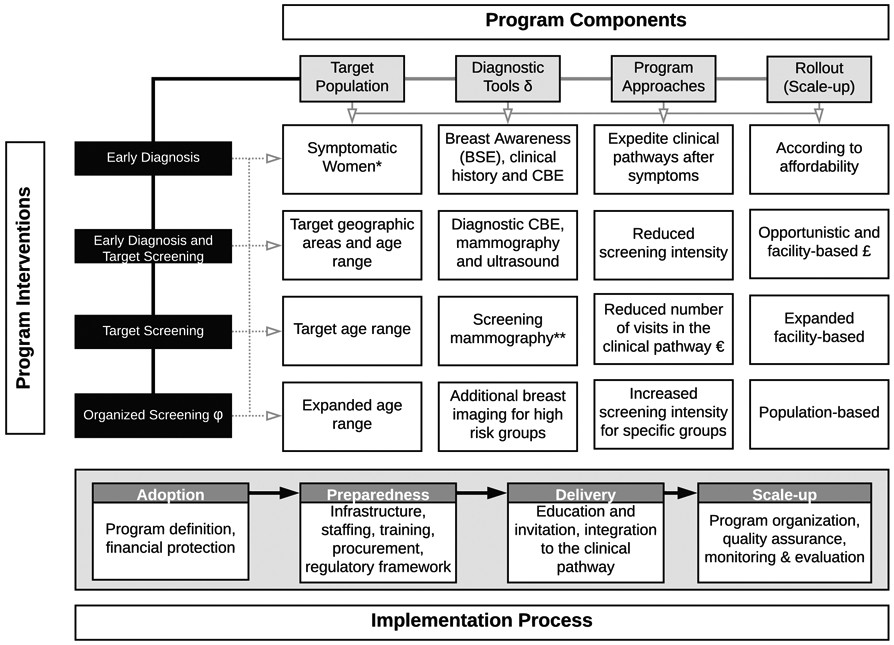

Building upon the Breast Health Global Initiative (BHGI)’s resource-stratified guidelines for early breast cancer detection, this discussion expands to provide a more detailed framework for policymakers and health planners. We outline “phases” in the development of early detection programs, commencing with management strategies for clinically detectable disease using history and physical examinations. Each phase necessitates continuous assessment and enhancement to ensure quality. Phased implementation operates on the principle that specific interventions require prerequisites and a structured order for effective implementation and scaling to achieve high-quality breast health care. These phases can be deployed sequentially or concurrently, depending on the specific implementation environment. Figure 2 provides an overview of this phased approach, which will be elaborated upon in subsequent sections.

Figure 2. Implementation Phases for Early Diagnosis and Detection Pathways

Alt text: Comprehensive flowchart outlining the phased implementation strategy for early breast cancer diagnosis and detection programs, emphasizing pathology services, clinical breast examination, mammography, and organized screening within a structured clinical pathway to enhance early detection.

This paper also addresses critical feasibility aspects such as finance and governance, which are essential for the successful planning and execution of breast cancer early detection programs. An iterative program improvement process is vital for sustained success across diverse resource settings. Furthermore, we present metrics for implementation, process, and clinical outcomes to gauge program feasibility, adoption, and effectiveness. Case studies from various countries will illustrate the challenges and opportunities inherent in implementing effective early breast cancer detection programs, considering the complex interplay of factors that facilitate or hinder achieving early detection in real-world scenarios. Understanding these factors is paramount to addressing the early diagnosis cost of care cancer effectively.

Implementation Phases: A Phased Approach to Early Detection and Cost-Effective Care

I. Early Diagnosis: Managing Clinically Detectable Disease and its Associated Costs

A fundamental challenge in establishing successful breast cancer programs is effectively managing clinically detectable disease equitably across the target population—all adult women presenting with signs or symptoms suggestive of breast cancer. A significant proportion of breast cancers in LMICs are diagnosed at advanced stages, ranging from 30–50% in Latin America to as high as 75% in Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of these advanced cancers are initially self-detected by patients, recognizing changes such as lumps or thickening. Upon presentation to the healthcare system with these symptoms, prompt and accurate diagnostic services are crucial to differentiate between benign and malignant conditions.

The capacity to diagnose and treat clinically detectable breast cancer begins with clinical breast assessment (CBA), involving medical history and focused physical examination, including clinical breast exam (CBE). CBE is followed by diagnostic imaging and tissue sampling with pathologic evaluation—the “triple test” of breast diagnosis. Prompt diagnosis, followed by surgery (at least modified radical mastectomy) and systemic therapy (chemotherapy and endocrine therapy), must be affordable and accessible. Pain and symptom management medications are also essential. Only after these basic diagnostic and treatment modalities are in place should more advanced options like breast-conserving surgery, radiotherapy, or targeted systemic therapies be considered. These factors significantly influence the early diagnosis cost of care cancer.

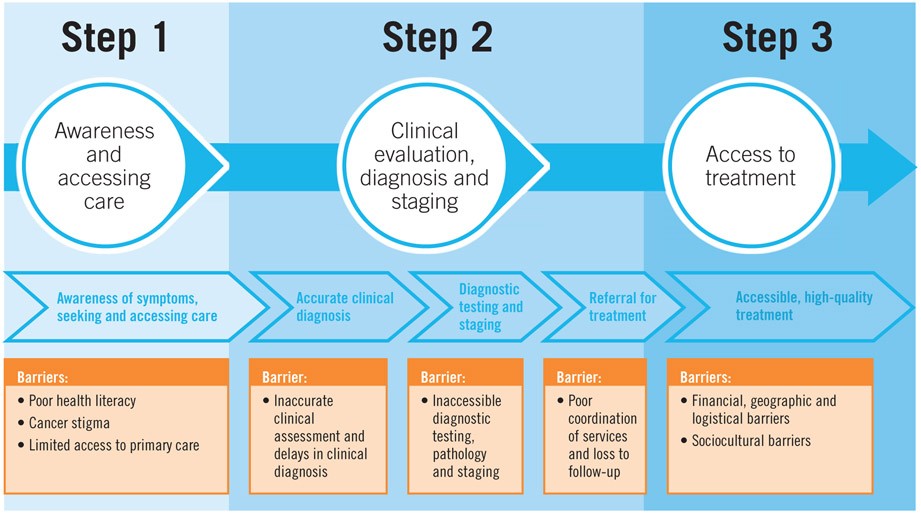

Delays exceeding three months in breast cancer treatment are linked to more advanced disease stages at diagnosis and poorer survival outcomes. Educating primary care providers to recognize early signs and symptoms of breast cancer is vital for timely referrals. Barriers to care, including structural, sociocultural, personal, and financial factors, must be identified and addressed to improve women’s access to care. Even with early symptom presentation, delays in diagnosis can occur if providers lack training, referral knowledge, or if the health system is fragmented. Figure 3a outlines strategies to overcome common barriers to early diagnosis, thereby impacting the overall cost of care cancer.

Figure 3a. Common Barriers to Early Diagnosis

Alt text: Graphic illustrating the common obstacles that women face in accessing early breast cancer diagnosis, categorized into patient-related, provider-related, and system-related barriers, highlighting factors like awareness, access to facilities, diagnostic delays, and financial constraints that affect the early diagnosis cost of care cancer.

Once high-quality, accessible services are available for diagnosing and treating clinically apparent disease, screening programs can be considered as a supplement to ongoing early diagnosis efforts. However, introducing screening programs without the capacity to manage detected abnormalities can be counterproductive, reinforcing negative perceptions about cancer curability and perpetuating late presentation cycles. This directly affects the perceived and actual early diagnosis cost of care cancer.

II. Early Diagnosis: Managing Image-Detected Disease and the Investment in Technology

Breast imaging, when accessible, is crucial for evaluating symptomatic women or those with suspicious clinical findings. Ultrasound, portable and versatile beyond breast imaging, is more widely available in LMICs than mammography. However, ultrasound’s effectiveness is highly operator-dependent and can have a high false negative rate if used for screening rather than palpable masses. The cost of care cancer is influenced by the availability and accuracy of these imaging technologies.

Mammography offers high specificity but reduced sensitivity in dense breasts. Mammography units are expensive and solely for breast imaging, limiting their accessibility in LMICs. Effective mammography, whether for screening or diagnosis, requires trained radiologists and radiographers, quality control, patient tracking, and effective communication, all contributing to significant operational costs.

Diagnostic ultrasound is indicated for women under 30 with focal breast symptoms and is comparable to mammography for women aged 30–39 at average breast cancer risk. Ultrasound differentiates cysts, benign masses, and suspicious masses and is less affected by breast density, making it preferable for younger women with denser breast tissue. While mammography’s diagnostic accuracy is similar in women aged 30–39, ultrasound is favored due to its ability to identify treatable causes of symptoms without radiation. Ultrasound is also valuable for women 40 and older, especially where mammography is unavailable or as an adjunct for diagnostic work-up, including axillary evaluation. The early diagnosis cost of care cancer is directly related to the choice and availability of these imaging modalities.

Diagnostic mammography is indicated for women 40 and older with breast symptoms, offering simultaneous screening. Mammography and ultrasound are used in combination to classify masses. Ultrasound further evaluates “probably benign” mammographic findings and guides biopsies. If mammography is unavailable, ultrasound is essential. Despite their value, medical imaging is not infallible. Women with negative imaging should still be clinically monitored, and surgical biopsy may be needed if clinical concerns persist despite imaging results.

Tissue sampling methods include fine needle aspiration (FNA), core biopsy, and excisional biopsy, each with varying characteristics and health system requirements. Excisional biopsy should not be the routine first diagnostic procedure. The choice of biopsy method also impacts the early diagnosis cost of care cancer, considering factors like invasiveness and diagnostic yield.

III. Population-Based Screening: Balancing Benefits and Costs in Early Detection Programs

Evidence for the efficacy of clinical breast examination (CBE) as a population-based screening tool is limited, particularly where mammography is not routine. While some studies show clinical downstaging with CBE, none have demonstrated improved breast cancer-specific survival or reduced mortality in population-based screening programs. However, if clinical downstaging via CBE screening can be achieved and coupled with timely, high-quality diagnostic and treatment services, mortality reduction is possible. Despite WHO not recommending population-based organized CBE screening in any resource setting, CBE is considered reasonable in lower-resource settings within a research context. A study in Peru indicated that women who had prior CBEs experienced shorter delays in seeking care and were more likely to be diagnosed at earlier stages. This suggests CBE as part of comprehensive breast health awareness may improve early diagnosis opportunities, potentially influencing the early diagnosis cost of care cancer in the long run.

A Brazilian study revealed that early detection policies, including public awareness and CBE/mammography screening since 2004, did not shift diagnoses from late to early stages significantly. Effective mammographic screening could have averted an estimated 2,500 deaths in 2012. However, downstaging patients from stage 3 or 4 to stage 2 could have prevented 8,000 deaths, suggesting clinical downstaging may have a greater impact than mammographic screening in settings with late-stage presentations. Further research is needed to address barriers to early breast cancer diagnosis. The cost of care cancer is intricately linked to the stage at diagnosis, emphasizing the importance of downstaging through early detection efforts.

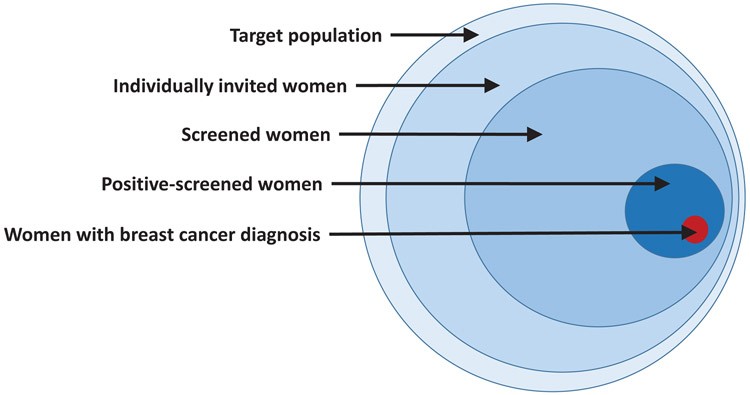

Population-based mammography screening, in contrast to CBE screening, has been associated with a significant 20% reduction in breast cancer mortality in high-income countries. However, successful mammography screening requires meticulous individual identification, invitation, and follow-up throughout the clinical pathway, ensuring access to screening, diagnosis, and treatment. This necessitates a robust health system, sustainable financing, and quality control, monitoring, and evaluation criteria, all contributing to the overall early diagnosis cost of care cancer.

Figure 4. Paradigm of Early Detection via Population-Based Screening

Alt text: Conceptual diagram illustrating the paradigm of early breast cancer detection through population-based screening programs, detailing the systematic steps from target population identification to screening, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up, essential for effective and cost-efficient cancer control.

Developing a population-based screening program, regardless of modality, should be within a national cancer control plan and health financing strategy. The financial implications, including mammography costs and supportive program costs, are substantial and must be balanced against other health priorities. Ensuring geographic access to diagnostic and treatment services is also critical, determined by infrastructure and workforce availability. Mobile units have been used to improve access, but their effectiveness requires further evaluation. These logistical considerations significantly influence the early diagnosis cost of care cancer.

Situational Analysis: Global Disparities and the Economic Impact of Late Diagnosis

Breast cancer survival rates vary significantly globally and are strongly correlated with a country’s GDP and public health expenditure. Human development indices, including national income, life expectancy, education, and fertility rates, alongside health system strength, impact a woman’s long-term breast cancer survival likelihood. Stage at diagnosis is a primary, measurable factor directly influencing survival. The early diagnosis cost of care cancer is profoundly affected by the stage at which cancer is detected.

A review of cancer control plans across 158 countries indicated fewer breast cancer early detection programs in LMICs compared to HICs. Even in HICs, disparities in access to early detection, diagnosis, and treatment exist. Inefficient referral pathways contribute to system delays and cancer disparities globally. Delays from symptom onset to diagnosis in sub-Saharan Africa can range from weeks to months. Less than half of cancer plans detail the role of primary care physicians and referral pathways in early breast cancer diagnosis. Untrained health workers are more prone to misdiagnosis. Both system and patient-related delays are significant factors influencing the overall cost of care cancer.

Expanding awareness or early diagnosis programs without concurrent expansion of diagnostic and treatment facilities can lead to poor outcomes, overwhelming health systems lacking capacity. This negates early detection benefits, erodes public trust, increases reliance on unorthodox treatments, and drives patients to costly private care. In Thailand, despite increased mammography availability, most were in private facilities with high out-of-pocket payments, straining public resources.

Beyond structural and financial barriers, access to early detection is also determined by the quantity and quality of healthcare human resources. Human resource needs for breast cancer screening and early diagnosis depend on national policies and guidelines. Workforce availability depends on the education system’s capacity and the health system’s ability to attract and retain providers. Policymakers must consider future demand from growing and aging populations and rising cancer incidence. Strengthening diagnostic skills in primary care and providing essential diagnostic tools (CBE, breast imaging, pathology) are crucial. Task-sharing and task-shifting, along with digital health and telemedicine, can address workforce shortages. The early diagnosis cost of care cancer is directly related to workforce capacity and training.

Diagnostic tools are performer-dependent, creating a trade-off between access and accuracy. Higher training levels improve accuracy but may reduce access. While data on early diagnosis of symptomatic disease are limited, strengthening diagnostic skills throughout the health system is essential, especially in low-income settings, to manage the early diagnosis cost of care cancer effectively. High-income countries face increasing demand and workforce shortages in breast imaging for screening.

The BCI2.5 Toolkit for Breast Cancer Situational Analyses: Practical Approaches to Reduce Costs and Improve Outcomes

The Breast Cancer Initiative 2.5 (BCI2.5) is a global campaign aimed at reducing breast cancer outcome disparities and improving breast healthcare access worldwide. It functions as a collaborative mechanism for advocacy and information dissemination to enhance independent and collective efforts and drive global investment in breast health care. Since 2014, BCI2.5 collaborations have produced resources and reports to help policymakers and health planners identify healthcare delivery bottlenecks and determine appropriate interventions. The BCI2.5 self-assessment toolkit aids countries in conducting comprehensive breast healthcare situational analyses. This toolkit helps in understanding the current early diagnosis cost of care cancer and identifying areas for cost reduction.

Five case scenarios illustrate the challenges and opportunities in achieving early breast cancer detection. In Appalachian Ohio, a program provides screening mammography and patient navigation to ensure follow-up for abnormalities. In China, a program trained breast cancer survivors as health ambassadors and educated healthcare providers to improve awareness and early detection, supported by multiple stakeholders to ensure treatment access. Mexico’s case demonstrates ongoing challenges in achieving early detection despite government, civil society, and academic efforts, highlighting the potential ineffectiveness of well-intentioned but poorly executed programs. Panama faced low screening participation, leading to a situational analysis revealing diagnostic delays and the need for an implementation strategy. Tanzania’s case describes a BCI2.5-facilitated situational analysis and recommendations, offering a model for countries with similar challenges. These case studies underscore the importance of context-specific strategies in managing the early diagnosis cost of care cancer.

Box 1. Case Study: Improving Access to Breast Cancer Screening in Appalachian Ohio: Addressing Disparities in Cost and Access

In Appalachian Ohio, marked by lower income and healthcare access, the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Center for Cancer Health Equity (OSUCCC-CCHE) initiated a breast screening program funded by the Susan G. Komen Foundation. This program includes a mobile mammogram van, community health workers (CHWs), and patient navigators (PNs). CHWs, native to Appalachia, educate women about breast screening. PNs at OSUCCC-CCHE assist women in accessing mammograms, addressing financial barriers (insurance, Medicaid, Ohio Breast and Cervical Early Detection Program, Komen funds, charity care), scheduling, and resolving barriers to appointments. CHWs and PNs ensure appointment completion and follow-up. To date, this program has provided mammograms to 952 Appalachian women, detected abnormalities in 73, ensured diagnostic resolution for 70, and diagnosed 6 with breast cancer (4 at an early stage). This case study highlights the effectiveness of targeted interventions in reducing the early diagnosis cost of care cancer by improving access and early detection in underserved communities.

Box 2. Case Study: China: Enhancing Awareness and Early Detection to Reduce Long-Term Costs

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among Chinese women, with survival rates lower than in many HICs. China lacks population-based screening programs. The Chinese National Breast Cancer Screening Program was discontinued due to funding and false-positive concerns. Current guidelines recommend mammography screening every 1–2 years for women aged 40–69, annual CBE, and monthly BSE. However, opportunistic screening rates are low (21.7–33.8%). The Eastern Michigan University Center for Health Disparities Innovation and Studies, funded by the Susan G. Komen Foundation, implemented a program to increase breast cancer awareness and early detection in China, based on BHGI recommendations. This included training breast cancer survivors as “breast health ambassadors,” educating community healthcare providers, and fostering multi-level collaboration to enhance follow-up and treatment capacity. The program trained approximately 2,000 ambassadors and over 800 providers across six provinces. Improving early detection through awareness and provider education can significantly reduce the long-term cost of care cancer by enabling earlier treatment and better outcomes.

Box 3. Case Study: Mexico: Re-evaluating Screening Strategies for Cost-Effective Early Diagnosis

Mexico’s NOM-041 guidelines recommend BSE, CBE, and mammography screening. Since 2007, treatment is government-covered for uninsured patients. Yet, most women are diagnosed with advanced-stage breast cancer, with long delays from symptom discovery to treatment. Despite significant investment in mammography screening promotion (USD 43.6 million in 2015), national screening coverage remains low (23%), and only 15% of breast cancer cases are detected via screening, due to human resource shortages for mammography interpretation. Increasing screening to WHO-recommended levels is financially and resource-wise challenging. Efforts to increase mammography screening have led to disorganized private services, often subcontracted by the government without quality assurance or follow-up. Symptomatic patients face long diagnostic and treatment delays due to a weak healthcare system. Neglected areas include strengthening primary care, ensuring diagnostic imaging quality, improving pathology access, and expedited referrals. The government is revising early detection practices to prioritize early diagnosis programs. This case highlights the need for strategic resource allocation to optimize the early diagnosis cost of care cancer and improve overall program effectiveness.

Box 4. Case Study: Panama: Addressing Diagnostic Delays to Improve Cost Efficiency

Panama’s Ministry of Health (MINSA) oversees healthcare, providing services to those without social security coverage. MINSA approved opportunistic breast cancer screening, but low participation led to symptomatic presentations at primary care facilities. Patients with symptoms are referred for diagnostic workup and confirmed cases to the National Oncology Institute (NOI) for free treatment. MINSA identified low breast cancer knowledge at primary levels and weak referral pathways as key areas for improvement. Standardized trainings were implemented to enhance primary care provider capacity for early detection and referral, using PAHO’s virtual platform. In 2018, BHGI and Susan G. Komen assessed barriers to early diagnosis, identifying opportunities to improve referral systems, increase needle biopsies to reduce surgical delays, and plan for increased patient influx at NOI. MINSA is developing a National Cancer Plan 2019–2029, focusing on strengthening early diagnosis and working with BHGI to implement strategies for core needle biopsies to reduce diagnostic delays. Addressing diagnostic delays is crucial for reducing the overall early diagnosis cost of care cancer and improving patient outcomes.

Box 5. Case Study: Tanzania: Phased Implementation for Sustainable and Cost-Effective Early Detection

In Tanzania, inefficient clinical pathways cause significant delays in breast cancer detection, diagnosis, and treatment, with 80% diagnosed at advanced stages. In 2016, a situational analysis by Susan G. Komen, BHGI, WEMA, and Ocean Road Cancer Institute assessed breast healthcare services, revealing non-standardized guidelines, inefficient referrals, financial barriers, workforce shortages, and poor communication. BHGI developed a resource-stratified, phased implementation framework focusing on managing palpable disease first, followed by strengthening care pathways, targeted education, and upgrading image-based diagnostics. This partnership led to harmonized national guidelines, primary care provider training, and implementation research. Phased implementation is a cost-effective strategy to build sustainable early detection programs and manage the early diagnosis cost of care cancer over time.

Across all case studies, late-stage diagnosis is a primary driver of poor survival, even in better-resourced settings. Multi-pronged efforts are needed to address various factors influencing women’s access to early breast cancer detection. These efforts should be strategically designed to optimize resource utilization and minimize the early diagnosis cost of care cancer.

Metrics for Early Detection of Breast Cancer: Measuring Program Effectiveness and Cost-Benefit

Establishing metrics to monitor and evaluate breast cancer early detection programs is crucial for program improvement and progress along a resource-stratified pathway. Effective metrics should be resource-appropriate, measurable, action-oriented, and regularly reported to stakeholders. Ideally, metrics should correlate with reduced breast cancer mortality, though evidence for such measures in LMICs is limited. These metrics are essential for assessing the cost of care cancer and program efficiency.

While mortality reduction is the ultimate goal, several metrics can evaluate program progress. In resource-rich settings with mammography screening, performance indicators can include the proportion of the target population screened within 24 months. Table 1 presents example metrics relevant across resource levels, grouped by resource level and metric type. An essential metric is the proportion of cancers diagnosed at different stages to monitor temporal trends in stage distribution, given its link to survival. In basic-resource settings, monitoring service availability across facilities is important. These metrics help in quantifying the impact of early detection programs on the early diagnosis cost of care cancer.

Table 1. Examples of Metrics to Identify and Track Outcomes

| Metric | Resource level (basic,core, enhanced,) | Metric type (process,implementation, healthoutcome) | User of the metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community breast cancer awareness:% aware of breast cancer symptoms,% knowing where to go for a breast health concern | Basic | Implementation metric, health outcome metric | System wideCommunity level/RegionalMinistry |

| Provider breast cancer awareness:% providers trained to provide high-quality clinical breast examinations,% providers knowing proper care referrals for positive CBE | Basic | Implementation metric, health outcome metric | System wideMedical education oversight?Health facility |

| Among women with suspected breast cancer, median days from symptom onset to first presentation at a health facility | Basic | Process metric | System wide-Community awareness-Access to care |

| Among women with suspected breast cancer, median days from first presentation at a health facility to diagnosis | Basic | Process metric | Health facility |

| Among patients diagnosed with breast cancer, median days from diagnosis to first treatment | Basic | Process metric | Health facility/network |

| % of patients with breast cancer diagnosed with early stage (stage I or II) disease | Basic | Health outcome metric | System wideHealth facility/network |

| % of patients lost to follow up after initial presentation with a breast mass | Basic | Health outcome metric | Health facility/network |

| % of relevant health facilities offering early detection services (penetration) | Basic-CBECore-UltrasoundEnhanced- Mammography | Implementation metric | Health system/Ministry |

| Uptake (population coverage) of routine screening services | Basic/Core-CBE Enhanced/ Mammography | Implementation metric | System wide |

| Cost | All levels | Implementation metric | System wide |

Table 1 Alt text: Table outlining key metrics for evaluating breast cancer early detection programs across different resource levels (basic, core, enhanced), categorizing metrics by type (process, implementation, health outcome) and intended users (system-wide, community, ministry), including metrics for awareness, provider training, diagnostic and treatment delays, stage at diagnosis, and program costs.

Financing Early Detection of Breast Cancer: Investment Strategies for Affordable Care

Financing early breast cancer detection interventions is justified from public health, economic, and equity perspectives. Late-stage diagnosis leads to catastrophic health expenditures and economic hardship across regions and resource levels. Non-medical costs (transport, lodging, childcare) can constitute up to 50% of total costs, risking impoverishment. Investing in early detection is economically sound and reduces the long-term cost of care cancer.

Effective prevention and early detection strategies can reduce costs and achieve significant savings for health systems and individuals, as early-stage cancers are less expensive to treat. A prevention/early detection/treatment strategy can yield approximately 60% economic savings compared to a treatment-only approach across regions. Cost-effectiveness analysis informs resource allocation for “Best Buy” interventions. Disease Control Priorities (DCP3) identified cost-effective interventions for LMICs, including public education on early detection value, risk factors, and breast health awareness. The DCP3 “essential package” would cost roughly $1.7-$5.7 extra per capita annually in LMICs. The 2017 WHO Global Action Plan did not include population-based mammography screening or stage 1 and 2 breast cancer diagnosis and treatment among “best buys,” but the WHO Commission on Macro-Economics and Health suggested international support for interventions not cost-effective for individual countries but still valuable. Strategic financing is crucial to manage the early diagnosis cost of care cancer effectively.

Essential packages depend on affordability. Governments may subsidize care or phase in interventions as resources grow, as seen in Mexico and Thailand. A combination of financing sources, emphasizing domestic funding, is needed. Public financing is key for public goods like education. A Malaysian case study showed a decline in late-stage presentation from 77% to 37% after awareness campaigns. Prioritizing health interventions and mobilizing public funds are essential amid competing health budget demands.

Social health insurance is an equitable way to fund early detection, diagnosis, and treatment, incorporating key interventions into benefit packages. Cost-sharing and private health insurance can supplement out-of-pocket spending. A tiered approach to increasing coverage as social health insurance matures may be important. Innovative financing options (tobacco, alcohol, sugar taxes, airline and mobile phone levies) can be considered. External financing can lower input costs and support technical assistance and research. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) can address bottlenecks but require strong oversight to ensure intended beneficiary reach without escalating costs. Diverse and innovative financing models are essential to sustainably manage the early diagnosis cost of care cancer.

Implementation Framework: Policies and Governance for Sustainable, Cost-Effective Programs

BHGI stratified guidelines and phased implementation strategies provide a framework for early detection policies based on resource levels, progressing from early diagnosis to organized screening. Policy implementation varies by setting, depending on health system capacity and characteristics. Robust policies and governance are essential for managing the early diagnosis cost of care cancer and ensuring program sustainability.

Developing and implementing breast cancer early detection policies requires accurate situational analyses, assessing sociopolitical and economic context, workforce capacity, infrastructure, geographic access, social structures, and funding. Policy development should include social scientists and target population representatives to ensure acceptability, equity, and inclusivity. Basic policy components include defining the target population, diagnostic tools, programmatic approaches, and rollout/scale-up processes. Financial protection mechanisms are crucial to minimize incomplete care and impoverishment, and including early detection in essential health packages is vital due to lower treatment costs for early-stage disease.

Policy implementation must ensure sustainability. In resource-limited settings, governmental expansion of health services may be constrained. Medical societies, survivor groups, and NGOs often fill gaps in awareness and early detection services, providing infrastructure, equipment, and staffing. However, these efforts must be integrated into existing health systems and coordinated with relevant ministries for lasting impact. NGOs should transition from service delivery to mainstreaming interventions with government commitment. Strong governance and policy frameworks are vital for the long-term cost-effectiveness and sustainability of early detection programs, impacting the overall early diagnosis cost of care cancer.

Conclusion: Towards a Future of Affordable and Accessible Early Detection

All countries face the challenge of meeting WHO Global Action Plan targets for non-communicable diseases and Sustainable Development Goals, aiming for a one-third reduction in NCD mortality by 2030. Breast cancer, the most common cancer in women globally, sees survival heavily dependent on timely, effective, and affordable care. Early detection, coupled with timely treatment, follow-up, and survivorship care, is critical for reducing breast cancer mortality and managing the early diagnosis cost of care cancer.

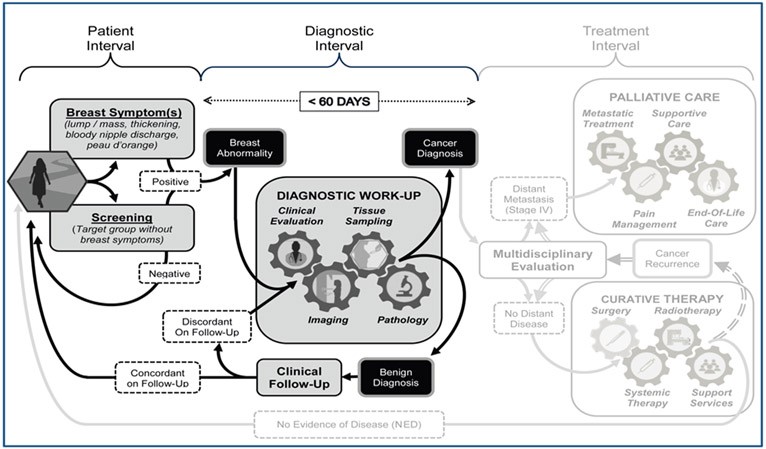

This discussion has presented the complex interplay of barriers to early detection, examples of interventions, sample metrics, and governance considerations, offering a practical framework for a phased approach to breast cancer early detection in any setting. A robust health system is a prerequisite for treating cancers detected through early detection programs. While patient and provider education can shorten patient intervals, achieving a diagnostic interval target of under 60 days requires coordination of clinical evaluation, imaging, tissue sampling, and pathological assessment. By strategically addressing each component of early detection and focusing on cost-effective implementation, we can move towards a future where early diagnosis of breast cancer is accessible and affordable for all women, ultimately reducing the human and economic burden of this disease.

Figure 5. Universal Patient Pathway for Breast Cancer Management

Alt text: Diagram illustrating the universal patient pathway for breast cancer management, divided into patient interval, diagnostic interval, and treatment interval, emphasizing the critical diagnostic interval of 60 days for effective early diagnosis and improved survival outcomes, directly impacting the early diagnosis cost of care cancer.

Figure 3b. Potential Interventions to Strengthen Early Diagnosis

Alt text: List of potential interventions aimed at strengthening early diagnosis of cancer, as recommended by the World Health Organization’s 2017 Guide to Cancer Early Diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the BHGI Global Summit was provided by grants from various organizations including the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Susan G. Komen, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, US National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute Center for Global Health, American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society of Clinical Pathology, Journal of Global Oncology, National Breast Cancer Foundation, Inc., pH Trust, Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, Union for International Cancer Control, and the University of Washington Department of Global Health. Unrestricted educational grants were received from Cepheid, GE Healthcare, Novartis, Pfizer Inc., and UE LifeSciences. Publication cost support was provided by GE Healthcare and Novartis.

The Susan G. Komen Leadership Grant (SAC170082) supported BOA, CD, and AD.

Dr. Paskett is the Multiple Principal Investigator on a grant from Merck Foundation and has received funding for a study in the past from Merck, not related to this paper’s topic. She has also been a Pfizer stockholder in the past three years.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement. The authors declare no conflicts of interest, except for Dr. Pasket’s disclosures mentioned above.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy, or views of the International Agency for Research on Cancer / World Health Organization, even where authors are identified as personnel of these organizations.

References

[1] WHO Guide to Cancer Early Diagnosis. World Health Organization. Geneva; 2017.

[2] Ginsburg O, Bray F, Coleman MP, Vanderpuye V, Eniu A, Fleming KA, et al. The global burden of women’s cancers: a grand challenge in global health. Lancet. 2017;389(10071):847–60. [PubMed]

[3] Anderson BO, Yip CH, Smith RA, Shyyan R, Sener SF, Eniu A, et al. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low-income and middle-income countries. Cancer. 2008;113(8 Suppl):2221–43. [PubMed]

[4] Anderson BO, Cazap E, El Saghir NS, Yip CH, Khaled HM, Popescu R, et al. Optimisation of breast cancer management in low-resource and middle-resource countries: executive summary of the Breast Health Global Initiative consensus, 2010. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(4):387–98. [PubMed]

[5] Peinado P, Moreno-Smith M, Jerez Y, Gomez H, Arrivillaga-Henríquez J, Villarreal-Garza C, et al. Breast cancer in Latin America: a systematic review of disparities in access to diagnosis and treatment. Breast. 2016;27:27–32. [PubMed]

[6] Adisa C, Bewernitz M, Chamberlain KJ, Adisa AO, Khuder S, Martin EW, et al. Predictors of advanced stage at diagnosis of breast cancer in sub-Saharan African women: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(3):279–86. [PubMed]

[7] Brewster DH, Stockton DL, Hart G, Hogg C, Stockton D, Morris GJ, et al. Factors influencing delay in presentation and diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(3):353–8. [PubMed]

[8] Villarreal-Garza C, Platas A, Dorantes-Gallareta Y, Angeles-Llerenas A, de la Garza-Salazar JG, Martinez-Cannon BA, et al. Effect of clinical breast examination on time to presentation and stage at diagnosis of breast cancer: a population-based study in Mexico. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;165(1):169–76. [PubMed]

[9] Dixon JM, Frances V, Anderson TJ, Lamb J, Nixon SJ, Freeman C, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology in relationship to clinical examination and mammography in the diagnosis of a breast mass. Br J Cancer. 1984;50(6):717–22. [PubMed]

[10] Yip CH, Smith RA, Anderson BO, Miller AB, Thomas DB, Ang PT, et al. Guideline for clinical breast examination: recommendations from the International Breast Health Initiative (IBHI). Cancer. 2008;113(8 Suppl):2184–2220. [PubMed]

[11] Cleary J, Powles J, Munene G, Mwangi-Powell F, Kiyange F, Gomes B, et al. Palliative care in Africa. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1581–92. [PubMed]

[12] Barton MB, Jacob S, Shafiq J, Wong R, Thompson JF, Evans G, et al. Estimating the optimal utilization of radiotherapy in oncology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89(2):165–9. [PubMed]

[13] Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB, Littlejohns P, McPherson K, Palmer CR, et al. Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet. 1999;353(9159):1119–26. [PubMed]

[14] Ramirez AJ, Westcombe AM, Burgess CC, Sutton S, Littlejohns P, Richards MA. Factors predicting delayed presentation of symptomatic breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet. 1999;353(9159):1127–31. [PubMed]

[15] Houssami N, Irwig L, Simpson JM, McKessar M, Blome S, Noakes J, et al. Sydney Breast Imaging Accuracy Study: comparative sensitivity and specificity of mammography and ultrasound in women with symptoms. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181(4):967–75. [PubMed]

[16] Stavros AT, Thickman D, Rapp CL, Dennis MA, Parker SH, Sisney GA. Solid breast nodules: use of sonography to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions. Radiology. 1995;196(1):123–34. [PubMed]

[17] Berg WA, Blume JD, Cormack JB, Mendelson EB, Lehrer D, Böhm-Vélez M, et al. Combined screening with ultrasound and mammography vs mammography alone in women at elevated risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 2008;299(18):2151–63. [PubMed]

[18] Kerlikowske K, Grady D, Barclay J, Sickles EA, Ernster V. Positive predictive value of screening mammography and diagnostic mammography in a community-based setting. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(11):825–30. [PubMed]

[19] Monticciolo DL, Newell MS, Moy L, Lee CS, Destounis SV, Currie CM, et al. Breast cancer screening in women at higher than average risk: recommendations from the ACR Commission on Breast Imaging. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(3 Pt A):408–14. [PubMed]

[20] Kösters JP, Gøtzsche PC. Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003373. [PubMed]

[21] Mittra I, Mishra GA, Dikshit R, Gupta S, Dhillon PK, Badwe RA. Effect of community-based screening for breast cancer on tumor stage distribution in Mumbai, India. JAMA. 2010;304(18):1978–84. [PubMed]

[22] World Health Organization. WHO position paper on mammography screening. World Health Organization. Geneva; 2014.

[23] Pace LE, Shulman LN, Strongin AU, Magrini N, Goetzsche PC. Screening mammography in low and middle income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(4):e129–30. [PubMed]

[24] Anderson BO, Jatoi I, Tse J, Rosenblatt E, Carlson RW. Breast cancer issues in low- and middle-resource countries. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(3):591–615. [PubMed]

[25] Marmot MG, Altman DG, Cameron DA, Dewar JA, Thompson SG, Wilcox M. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(10):2205–40. [PubMed]

[26] Jatoi I, Anderson BO. Breast cancer screening in low and middle resource countries. Breast J. 2003;9(Suppl 2):S87–92. [PubMed]

[27] Burdick JS, Hill J, Kim ES, Guerry E, Griffith R, Johnson K, et al. The use of mobile mammography to improve access to breast cancer screening in underserved women. J Am Coll Radiol. 2008;5(1):8–15. [PubMed]

[28] Yaffe MJ, Baily AJ, Flowerdew G, Miller AB, Muller JW, Shaw A, et al. Effect of mobile mammography screening on rates of screening and stage at diagnosis of breast cancer. CMAJ. 2002;166(13):1641–7. [PubMed]

[29] Allemani C, Weir HK, Carreira H, Harewood R, Spika D, Wang XS, et al. Global surveillance of cancer survival 1995–2009 (CONCORD-2): analysis of individual patient data for 25,676,887 adults from 279 population-based cancer registries in 67 countries. Lancet. 2015;385(9972):977–1010. [PubMed]

[30] Hortobagyi GN, de la Garza Salazar J, Pritchard KI, Amadori D, Haidinger R, Hudis CA, et al. The global breast cancer burden: variations in epidemiology and survival. Clin Breast Cancer. 2005;6(5):391–401. [PubMed]

[31] de Vries E, Torre LA, Dei Tos AP, Bray F, Coebergh JW, Weber WP, et al. Cancer control in Europe and Central Asia: policy trends and unmet needs. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(5):781–90. [PubMed]

[32] Freeman HP. The unequal burden of cancer in the United States: racial and ethnic minorities and the poor. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(2):85–100. [PubMed]

[33] Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Race, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer treatment and survival. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51(5):284–301. [PubMed]

[34] Shavers VL, Brown ML. Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(5):334–57. [PubMed]

[35] Surbone A, Baider L, Perez-Stable EJ, Wassersug J, Bjelic-Radisic V, Serin J, et al. The sociocultural context of cancer: a qualitative study of advanced cancer patients in eight countries. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43(1):144–55. [PubMed]

[36] Neal RD, Allgar VL. Sociodemographic factors and delays in diagnosing cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(11):1971–9. [PubMed]

[37] Cubasch H, Dickens C, Joffe M, Goedhals L, Wright C, Jacobson BF, et al. Breast cancer stage at diagnosis and delay to diagnosis in Johannesburg, South Africa. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;153(2):369–77. [PubMed]

[38] Chokunonga E, Nyakabau AM, Chirenje ZM, Ndemera B, Chifamba J, Matenga J, et al. Cancer misdiagnosis in primary health care settings in Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med. 2000;46(12):326–9. [PubMed]

[39] Teerawattananon Y, Mugford M, Tangcharoensathien V, Tangcharoensathien V, Sriratanaban A, Patmasiriwat P, et al. Economic evaluation of population-based mammography screening for breast cancer in Thailand. Value Health. 2007;10(4):268–78. [PubMed]

[40] World Health Organization. Task shifting: global recommendations and guidelines. World Health Organization. Geneva; 2008.

[41] Jatoi I, Baum M, Downey C, English R, Shapiro M, Banks E, et al. Breast cancer screening in resource-poor countries. Breast. 2013;22(6):733–42. [PubMed]

[42] Sankaranarayanan R, Swaminathan R, Brenner H, Chen K, Dos-Santos-Silva I, Evans G, et al. Cancer survival in Africa, Asia, and Central and South America: Early detection and implications for global health equity. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(4):340–56. [PubMed]

[43] Khoja S, Durrani H, Nayani P, Majeed-Ariss R, Vaswani V, Osmond M, et al. Global e-health readiness assessment: e-health readiness assessment framework and tool-kit version 1. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(6):e147. [PubMed]

[44] Bashshur RL, Shannon GW, Krupinski EA, Grigsby J. The empirical evidence for telemedicine interventions in cancer care. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(9):693–712. [PubMed]

[45] Nelson EL, Walker BB, Mobley LR, Harrison RA, Simon CJ. Telemedicine and underserved rural populations: current status and future directions. J Rural Health. 2005;21(4):336–44. [PubMed]

[46] Silva MJ, Pinheiro PS, Fairley TL, Patel DA, Mayor M, Stewart SL. Telemedicine in cancer control: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(4):222–33. [PubMed]

[47] Dhillon PK, Lakhani M, Nanda S, Abraham R, Sharma S, Banavali S, et al. Use of mobile technology to improve adherence to oral chemotherapy: a pilot study. JCO Glob Oncol. 2017;3:415–21. [PubMed]

[48] Miller AB, Wall C, Baines CJ, Sun P, Ghadirian P, Miller N, et al. Twenty-five year follow-up of a randomized trial of breast cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(18):1490–9. [PubMed]

[49] Tabár L, Vitak B, Chen TH, Yen AM, Cohen A, Tot T, et al. Swedish two-county trial: impact of mammographic screening on breast cancer mortality during 3 decades. Radiology. 2011;260(3):658–63. [PubMed]

[50] Brodersen J, Siersma VD. Long-term psychosocial consequences of false-positive screening mammography. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):73–9. [PubMed]

[51] Yen AM, Chen SL, Fann JC, Chang YC, Chiu SY, Chen LS, et al. Population-based breast cancer screening with mammography: evidence from the National Taiwan Cancer Registry. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127(3):727–34. [PubMed]

[52] Breast Cancer Initiative 2.5 (BCI2.5) Breast Health Global Initiative. 2019. http://www.bhgi.info/bci2-5/ [Accessed 18 Nov 2019].

[53] Breast Health Global Initiative (BHGI). Breast Health Global Initiative Needs Assessment Tool kit. 2014. http://www.bhgi.info/bhgi-needs-assessment-tool-kit/ [Accessed 18 Nov 2019].

[54] Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC). Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. 2019. https://www.bcsc-research.org/ [Accessed 18 Nov 2019].

[55] Hortobagyi GN, Abdalla IA, Garcia-Manero G, Raber MN, Fritsche HA, Legha SS, et al. Cost analysis of breast cancer care, 1991. Cancer. 1994;73(3 Suppl):784–91. [PubMed]

[56] Bloom DE, Cafiero JA, Jané-Llopis E, Abrahams-Gessel S, Park MJ, Levin CV, et al. The global economic burden of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Economic Forum; 2011.

[57] Ginsburg OM, Soliman AS, Habib M, Boffetta P, Brennan P. Burden of breast cancer in North Africa and Middle East: 1990–2013. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(11):2759–69. [PubMed]

[58] Wilson R, Srigley J, De Coster C, Robson P, van Ineveld C, Cukier P, et al. Prevention and early detection: economic evaluation of strategies to reduce cancer burden in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2013;104(3):e210–6. [PubMed]

[59] Disease Control Priorities 3rd edition: Cancer. Disease Control Priorities. 2015. https://dcp-3.org/cancer [Accessed 18 Nov 2019].

[60] Global action plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013–2020. World Health Organization. 2017. https://www.who.int/ncds/global-action-plan/en/ [Accessed 18 Nov 2019].

[61] Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Macroeconomics and health: investing in health for economic development: report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. World Health Organization. Geneva; 2001.

[62] Knaul FM, Arreola-Ornelas H, Wong R, Lugo-Palacios DG, Mendez O, Torres-Sanchez L, et al. Breast cancer in Mexico: a pressing health priority. JCO Glob Oncol. 2017;3:132–42. [PubMed]

[63] Tangcharoensathien V, Patcharanarumol W, Ir P, Mills A. Thailand’s universal coverage scheme: how did they do it? Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(1):61–3. [PubMed]

[64] Tangcharoensathien V, Witthayapipopsakul W, Panichkriangkrai W, Pitayarangsarit S, Mills A. Universal coverage policy reforms in Thailand: strategies for success. Lancet. 2018;391(10122):861–72. [PubMed]

[65] Taib NA, Yip CH, Low WY, Abdul Rahman R, Ibrahim M, Ho GF, et al. Breast cancer awareness program: impact on stage at diagnosis and survival in Malaysian women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(11):5843–8. [PubMed]

[66] Jamison DT, Summers LH, Alleyne G, Arrow KJ, Berkley S, Binagwaho A, et al. Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation. Lancet. 2013;382(9908):1898–955. [PubMed]

[67] Horton R, Das P. Global health 2035: time to get serious. Lancet. 2013;382(9908):1887–8. [PubMed]

[68] Yip CH, Anderson BO. Breast cancer early detection in low and middle income countries. Breast J. 2013;19(Suppl 1):3–4. [PubMed]

[69] Jatoi I, Anderson BO. Screening for breast cancer in low- and middle-income countries. World J Surg. 2011;35(7):1476–83. [PubMed]

[70] Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–58. [PubMed]

[71] United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United Nations. New York; 2015.