Establishing an accurate pulpal and periapical diagnosis is not just a preliminary step in endodontics; it’s the bedrock upon which effective clinical treatment plans are built. For dental professionals, a precise Endo Diagnosis is paramount to ensuring patients receive the most appropriate and necessary care, avoiding both overtreatment and undertreatment.

Historically, the landscape of endodontic diagnostic classification has been varied and often convoluted. Many systems were rooted in histopathological findings rather than practical clinical observations. This approach frequently led to confusion, misinterpretations of terminology, and ultimately, diagnostic inaccuracies. The critical shift towards clinically relevant diagnostic criteria is essential because the primary purpose of endo diagnosis is to guide clinical decision-making. Misdiagnosis can lead down the wrong treatment path – potentially resulting in unnecessary endodontic procedures or, conversely, neglecting to perform a needed root canal when other treatments are insufficient.

Beyond individual patient care, a standardized and universally accepted diagnostic system is crucial for clear and consistent communication within the dental community. Educators, clinicians, students, and researchers all benefit from a common language. A simple, clinically focused system using terms grounded in observable findings empowers practitioners to understand the progressive nature of pulpal and periapical diseases. This understanding, in turn, directs them to the most suitable treatment strategy for each unique clinical situation.

Recognizing the imperative for standardization, the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) convened a consensus conference in 2008. This landmark event aimed to establish universal recommendations for endodontic diagnoses and to develop standardized definitions for key diagnostic terms. The goal was to create a lexicon that would be broadly accepted and utilized by endodontists, educators, testing bodies, insurance providers, general dentists, specialists, and students alike. Furthermore, the conference addressed concerns surrounding testing methodologies and the interpretation of results, and sought to define the radiographic, objective, and clinical criteria necessary to validate the established diagnostic terms. The AAE and the American Board of Endodontics have officially adopted these terms, advocating for their consistent application across all dental specialties and healthcare professions.

This article will delve into each of these standardized diagnostic terms, detailing the typical clinical and radiographic characteristics associated with each condition. We will also provide illustrative case examples to further clarify their application in practice. It is crucial for clinicians to remember that pulp and periapical diseases are dynamic processes, evolving over time. Consequently, the signs and symptoms presented can vary significantly depending on the disease stage and the individual patient’s overall health. Adding to the complexity are the inherent limitations of current pulp testing modalities and clinical and radiographic examination techniques. Therefore, to formulate a correct and comprehensive treatment plan, a complete endo diagnosis must encompass both a pulpal and a periapical assessment for every tooth under evaluation.

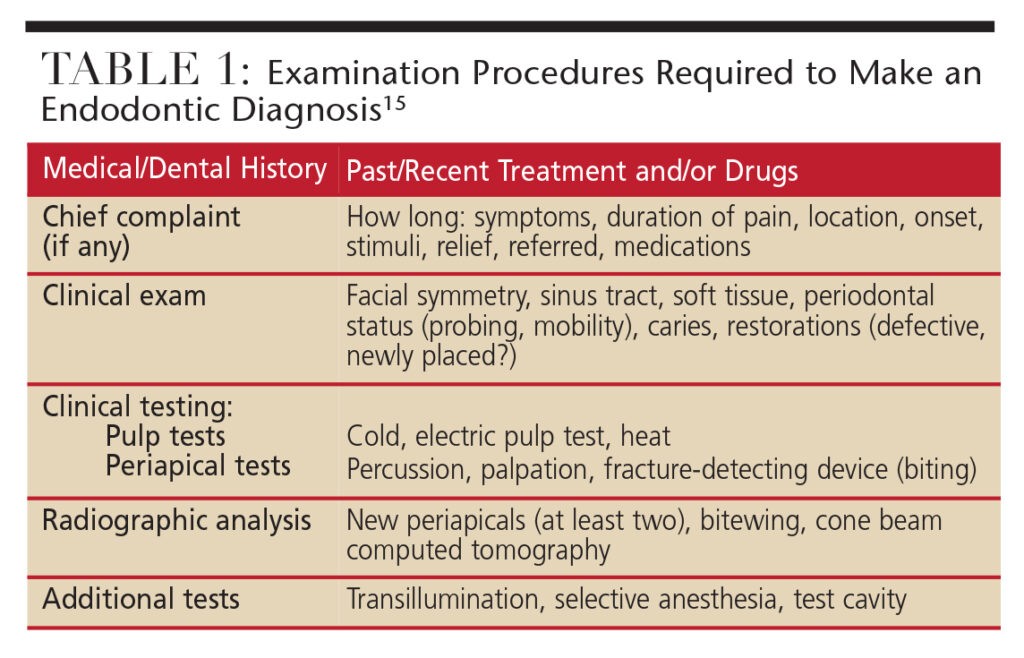

Endo Diagnosis Procedures Table: Steps for Pulpal and Periapical Assessment in Dentistry

Endo Diagnosis Procedures Table: Steps for Pulpal and Periapical Assessment in Dentistry

Examination and Diagnostic Procedures: Assembling the Endo Diagnosis Puzzle

Endo diagnosis is not about finding a single, definitive piece of information; it’s akin to assembling a jigsaw puzzle. A diagnosis cannot be accurately made based on isolated findings. Clinicians must systematically gather all relevant information to arrive at a “probable” diagnosis. The diagnostic journey begins with a comprehensive review of the patient’s medical and dental history. Even at this stage, clinicians should start formulating a preliminary, logical diagnosis, especially if the patient presents with a chief complaint. Clinical and radiographic examinations, coupled with a thorough periodontal evaluation and specific clinical tests (such as pulp and periapical tests), serve to confirm or refine this preliminary diagnosis.

However, it’s important to acknowledge that in some instances, clinical and radiographic examinations can yield inconclusive or even contradictory results. In such cases, definitive pulpal and periapical diagnoses may not be immediately attainable. It’s a fundamental principle that treatment should never be initiated without a clear diagnosis. In situations where diagnostic clarity is lacking, it may be necessary to defer treatment, reassess the patient at a later appointment, or refer them to an endodontist for specialized evaluation.

Diagnostic Terminology Approved by the American Association of Endodontists and American Board of Endodontics

Pulpal Diagnoses: Understanding Pulp Health and Disease

Normal Pulp: This clinical diagnostic category describes a pulp that is symptom-free and responds normally to pulp testing. While histologically, the pulp might not be perfectly “normal,” a clinically normal pulp exhibits a mild and transient response to thermal (cold) testing. This response should last no more than one to two seconds after the stimulus is removed. A crucial aspect of determining a “normal” pulp response is comparative testing. Always compare the tooth in question to adjacent and contralateral teeth. It is best practice to test adjacent and contralateral teeth first to familiarize the patient with the sensation of a normal cold response, establishing a baseline.

Reversible Pulpitis: This diagnosis is based on subjective and objective findings that indicate inflammation that should resolve, allowing the pulp to return to its normal healthy state, provided the causative etiology is appropriately managed. Patients with reversible pulpitis typically experience discomfort when a stimulus, such as cold or sweetness, is applied. Critically, the pain subsides within a couple of seconds after the stimulus is removed. Common causes include exposed dentin (dentinal sensitivity), dental caries, or deep restorations. Radiographically, there are no significant changes in the periapical region of the affected tooth, and the pain is not spontaneous. Following management of the underlying cause (e.g., caries removal and restoration, or covering exposed dentin), the tooth requires follow-up evaluation to confirm the reversible pulpitis has indeed resolved and the pulp has returned to a normal status. It’s worth noting that while dentinal sensitivity itself is not an inflammatory process, its symptoms closely mimic those of reversible pulpitis.

Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis: This diagnosis indicates a vital, inflamed pulp that is incapable of healing. Root canal treatment is the indicated course of action. Characteristics of symptomatic irreversible pulpitis may include sharp pain upon thermal stimulus, lingering pain (often lasting 30 seconds or longer after stimulus removal), spontaneous pain (pain that arises without provocation), and referred pain (pain felt in a location other than the originating tooth). Patients may also report pain intensification with postural changes, such as lying down or bending over. Over-the-counter analgesics are typically ineffective in alleviating the pain. Common etiologies include deep caries, extensive restorations, or tooth fractures that expose the pulpal tissues. Teeth with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis can sometimes be diagnostically challenging because the inflammation might not yet have extended to the periapical tissues. Consequently, percussion may not elicit pain. In these situations, the patient’s dental history and thermal testing become paramount in assessing pulpal status.

Asymptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis: This clinical diagnosis also indicates a vital, inflamed pulp that is beyond healing, necessitating root canal treatment. However, unlike symptomatic irreversible pulpitis, these cases present with no clinical symptoms. The tooth usually responds normally to thermal testing, but the patient history might reveal trauma or deep caries that would likely lead to pulp exposure upon caries removal.

As with pulp testing, comparative testing for percussion and palpation should always begin with normal teeth as a baseline

Pulp Necrosis: This diagnostic category denotes the death of the dental pulp, definitively requiring root canal treatment. A necrotic pulp will not respond to pulp testing and is typically asymptomatic in itself. Pulp necrosis alone does not cause apical periodontitis (i.e., pain to percussion or radiographic evidence of bone breakdown) unless the root canal system becomes infected. It’s important to consider that some teeth may be non-responsive to pulp testing due to pulp canal calcification, a recent history of trauma, or simply because the tooth is temporarily non-responsive. This underscores the importance of comparative testing – for example, a patient might not respond to thermal testing on any teeth, indicating a systemic issue or testing anomaly rather than widespread pulp necrosis.

Previously Treated: This diagnostic category is used when a tooth has already undergone endodontic treatment, and the root canals are obturated with filling materials (other than intracanal medicaments). These teeth typically do not respond to thermal or electric pulp testing.

Previously Initiated Therapy: This category applies when a tooth has received partial endodontic therapy, such as a pulpotomy or pulpectomy. Depending on the extent of the prior treatment, the tooth may or may not respond to pulp testing modalities.

Key Takeaways for Pulpal Diagnosis:

- Accurate pulpal and periapical diagnosis is essential for determining the correct endodontic treatment.

- A universal and clinically-focused diagnostic classification system is vital for clear communication and effective treatment planning.

- This standardized system helps clinicians understand the progression of pulpal and periapical diseases and guides them to the most appropriate treatment.

- The AAE and American Board of Endodontics endorse these diagnostic terms for use across all dental disciplines.

- A complete endo diagnosis necessitates both pulpal and periapical assessments for each tooth.

- When in doubt, general practitioners should always refer patients to an endodontist for expert evaluation.

Apical Diagnoses: Assessing Periapical Tissue Health

Normal Apical Tissues: Normal apical tissues are not sensitive to percussion or palpation testing. Radiographically, the lamina dura surrounding the root apex is intact, and the periodontal ligament space exhibits a uniform width. Similar to pulp testing, comparative testing for percussion and palpation should always start with normal teeth to establish a baseline for the patient.

Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis: This diagnosis represents inflammation, typically localized to the apical periodontium, that produces clinical symptoms. These symptoms include pain upon biting and/or percussion or palpation. Symptomatic apical periodontitis may or may not be accompanied by radiographic changes. Depending on the stage of the disease, the periodontal ligament space might appear normal in width, or a periapical radiolucency (darker area) may be evident. Severe pain upon percussion and/or palpation is a strong indicator of a degenerating pulp, and root canal treatment is generally required.

Asymptomatic Apical Periodontitis: This condition involves inflammation and destruction of the apical periodontium originating from pulpal pathology. It is characterized by the presence of an apical radiolucency on radiographs but lacks clinical symptoms. Patients with asymptomatic apical periodontitis do not experience pain on percussion or palpation.

Chronic Apical Abscess: This is an inflammatory reaction to pulpal infection and necrosis. It is characterized by a gradual onset, often with minimal or no discomfort. A hallmark of a chronic apical abscess is the intermittent discharge of pus through an associated sinus tract (a pathway for drainage). Radiographically, signs of bone destruction, such as a radiolucency, are typically present. To identify the tooth responsible for a draining sinus tract, a gutta-percha cone can be carefully inserted into the sinus tract opening until it meets resistance. A radiograph is then taken to trace the sinus tract back to its origin.

Acute Apical Abscess: This represents an inflammatory reaction to pulpal infection and necrosis with a rapid onset. Patients experience spontaneous pain, extreme tenderness of the tooth to pressure, pus formation, and swelling of surrounding tissues. Radiographic signs of bone destruction may be absent, particularly in the early stages. Patients may also exhibit systemic symptoms such as malaise, fever, and lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes).

Condensing Osteitis: This is a diffuse, radiopaque lesion (whiter area on a radiograph) representing a localized bony reaction to a low-grade inflammatory stimulus. It is typically observed at the apex of the tooth.

Diagnostic Case Examples: Applying Endo Diagnosis in Practice

Figure 1. This mandibular right first molar had previously been hypersensitive to cold and sweets, but these symptoms have now subsided. Currently, there is no response to thermal testing, but the tooth is tender to biting and painful upon percussion. Radiographically, diffuse radiopacities are visible around the root apices. Diagnosis: Pulp necrosis; symptomatic apical periodontitis with condensing osteitis. Non-surgical endodontic treatment is indicated, followed by a build-up and crown restoration. Over time, the condensing osteitis is expected to partially or completely resolve.

Figure 2. Following the placement of a full gold crown on the maxillary right second molar, the patient reported sensitivity to both hot and cold liquids. This discomfort has now become spontaneous. Thermal testing with a pulp vitality refrigerant spray on this tooth elicited pain, and the discomfort lingered for 12 seconds after stimulus removal. Responses to both percussion and palpation were normal. Radiographically, no osseous changes were evident. Diagnosis: Symptomatic irreversible pulpitis; normal apical tissues. Non-surgical endodontic treatment is indicated. Access will be repaired with a permanent restoration. Note the severe distal caries on the maxillary second premolar. Following evaluation, this tooth was diagnosed with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis (hypersensitive to cold, lingering pain for eight seconds) and symptomatic apical periodontitis (pain to percussion).

Figure 3. The maxillary left first molar presents with occlusal-mesial caries. The patient reports sensitivity to sweets and cold liquids. There is no discomfort upon biting or percussion. The tooth is hyperresponsive to thermal (cold) testing, with no lingering pain. Diagnosis: Reversible pulpitis; normal apical tissues. Treatment would involve caries excavation followed by placement of a permanent restoration. If pulp exposure occurs during caries removal, non-surgical endodontic treatment followed by a permanent restoration, such as a crown, would be necessary.

Figure 4. This mandibular right lateral incisor exhibits an apical radiolucency discovered during a routine examination. The patient has a history of trauma to the tooth more than 10 years prior, and the tooth is slightly discolored. The tooth did not respond to thermal (cold) testing or electric pulp testing, while adjacent teeth responded normally to pulp testing. There was no tenderness to percussion or palpation in the region. Diagnosis: Pulp necrosis; asymptomatic apical periodontitis. Treatment involves non-surgical endodontic therapy, followed by bleaching and a permanent restoration.

Figure 5. The mandibular left first molar demonstrates a relatively large apical radiolucency encompassing both the mesial and distal roots, with furcation involvement. Periodontal probing depths were within normal limits. The tooth did not respond to thermal (cold) testing, and both percussion and palpation elicited normal responses. A draining sinus tract was present on the midfacial aspect of the attached gingiva, which was traced with a gutta-percha cone. Recurrent caries were noted around the distal margin of the crown. Diagnosis: Pulp necrosis; chronic apical abscess. Treatment includes crown removal, non-surgical endodontic treatment, and placement of a new crown.

Figure 6. The maxillary left first molar underwent endodontic treatment more than 10 years ago. The patient now complains of pain upon biting for the past three months. Apical radiolucencies appear to be present around all three roots. The tooth is tender to both percussion and use of a fracture-detecting device. Diagnosis: Previously treated; symptomatic apical periodontitis. Treatment is non-surgical endodontic retreatment, followed by permanent restoration of the access cavity.

Figure 7. This maxillary left lateral incisor exhibits an apical radiolucency. There is no history of pain, and the tooth is asymptomatic. There is no response to thermal (cold) testing or electric pulp testing, while adjacent teeth respond normally to both tests. No tenderness to percussion or palpation is present. Diagnosis: Pulp necrosis; asymptomatic apical periodontitis. Treatment is non-surgical endodontic therapy and placement of a permanent restoration.

Conclusion: Endo Diagnosis – Guiding the Path to Endodontic Success

Recognizing that the central purpose of establishing an accurate pulpal and periapical diagnosis is to direct appropriate clinical treatment, dental professionals can effectively utilize this universal classification system to ensure sound clinical management in endodontics. The AAE and American Board of Endodontics have endorsed these diagnostic terms, recommending their consistent application across all dental specialties. While this practical system significantly reduces potential diagnostic confusion, clinicians must remain mindful that diseases of the pulp and periapical tissues are dynamic and progressive. Consequently, the presented signs and symptoms will vary based on the stage of the disease process and the individual patient’s condition.

It is vital to reiterate that an accurate endo diagnosis is not derived from a single, isolated piece of information. Treatment should never be rendered without a definitive diagnosis. In situations where diagnostic uncertainty persists, general practitioners should always err on the side of caution and refer patients to a qualified endodontic specialist for further evaluation and management.

References

- Glickman GN. AAE consensus conference on diagnostic terminology: background and perspectives. J Endod. 2009;35:1619.

- Seltzer S, Bender IB, Ziontz M. The dynamics of pulp inflammation: correlations between diagnostic data and actual histologic findings in the pulp. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1963;16:846–871;969–977.

- Berman LH, Hartwell GR. Diagnosis. In: Cohen S, Hargreaves KM, eds. Pathways of the Pulp, 11th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby/Elsevier; 2011:2–39.

- Schweitzer JL. The endodontic diagnostic puzzle. Gen Dent. 2009;57(6):560–567.

- AAE Consensus Conference Recommended Diagnostic Terminology. J Endod. 2009;35:1634.

- American Association of Endodontists. Glossary of Endodontic Terms. 8th ed. 2012.

- Glickman GN, Bakland LK, Fouad AF, Hargreaves KM, Schwartz SA. Diagnostic terminology: report of an online survey. J Endod. 2009;35:1625.

- Jafarzadeh H, Abbott PV. Review of pulp sensibility tests. Part I: general information and thermal tests. Int Endod J. 2010;43:738–762.

- Jafarzadeh H, Abbott PV. Review of pulp sensibility tests. Part II: electric pulp tests and test cavities. Int Endod J. 2010;43:945–958.

- Newton CW, Hoen MM, Goodis HE, Johnson BR, McClanahan SB. Identify and determine the metrics, hierarchy, and predictive value of all the parameters and/or methods used during endodontic diagnosis. J Endod. 2009;35:1635.

- Levin LG, Law AS, Holland GR, Abbot PV, Roda RS. Identify and define all diagnostic terms for pulpal health and disease states. J Endod. 2009;35:1645.

- Gutmann JL, Baumgartner JC, Gluskin AH, Hartwell GR, Walton RE. Identify and define all diagnostic terms for periapical/periradicular health and disease states. J Endod. 2009;35:1658.

- Rosenberg PA, Schindler WG, Krell KV, Hicks ML, Davis SB. Identify the endodontic treatment modalities. J Endod. 2009;35:1675.

- Green TL, Walton RE, Clark JM, Maixner D. Histologic examination of condensing osteitis in cadaver specimens. J Endod. 2013;39:977–979.

- Abbott PV, Yu C. A clinical classification of the status of the pulp and the root canal system. Aust Dent J. 2007;52(Endod Suppl):S17–S31.