Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI), commonly referred to as hip impingement, is a condition where abnormal contact occurs between the hip socket (acetabulum) and the upper part of the thigh bone (femoral head-neck junction). This mechanical issue can lead to pain and damage within the hip joint. Fai Diagnosis is crucial for effective management and preventing long-term complications like osteoarthritis. This article delves into the intricacies of FAI, covering its types, presentation, diagnostic methods, and treatment options, providing a comprehensive understanding for accurate FAI diagnosis.

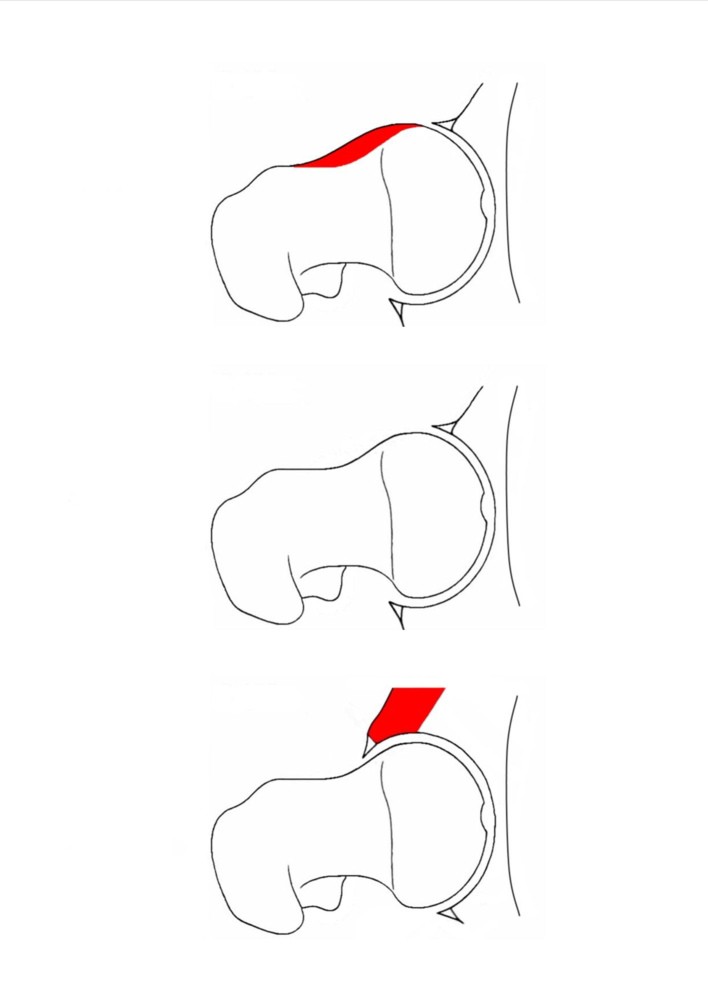

FAI is primarily caused by bony overgrowths that alter the normal hip joint anatomy. These deformities are categorized into two main types: cam and pincer. Cam deformities involve an excess of bone on the femoral head-neck junction, often described as a ‘bump’ that isn’t normally present. Pincer deformities, on the other hand, are characterized by an overcoverage of the femoral head by the acetabulum, often due to abnormal acetabular shape or orientation. Many individuals may also present with a combination of both cam and pincer deformities, known as mixed impingement. It’s important to note that impingement can also occur in hips with normal bone structure, particularly in athletes or individuals with extreme ranges of motion, such as dancers and gymnasts. In these cases, repetitive movements can still lead to the femoral neck contacting the acetabular rim.

The repeated impact caused by FAI can damage the soft tissues within the hip joint, specifically the labrum (a ring of cartilage that helps stabilize the hip) and the articular cartilage (the smooth surface covering the bones). Over time, this repetitive injury can lead to tears in the labrum and cartilage damage, potentially progressing to osteoarthritis (OA). Research increasingly links FAI to the development of hip OA. Population studies have shown that cam and pincer deformities are prevalent in a significant percentage of individuals with hip OA. Longitudinal studies further support the association between FAI and the subsequent development of degenerative joint disease. Early and accurate FAI diagnosis is therefore essential to mitigate these risks.

Recognizing FAI: Presentation and Symptoms for Accurate Diagnosis

FAI typically affects active adults, most commonly between 25 and 50 years of age. In older individuals, FAI is often found alongside pre-existing osteoarthritis. The most common symptom prompting FAI diagnosis is deep, intermittent hip discomfort, often experienced during or after physical activity. A detailed pain history is a crucial first step in the diagnostic process.

Anterior impingement, resulting from either cam or pincer deformities, is typically characterized by groin pain that occurs during or after activities involving repetitive or sustained hip flexion. Activities that commonly exacerbate anterior impingement symptoms include sprinting, kicking sports, hill climbing, and prolonged sitting, especially in low chairs. Pain may also radiate to the anterior thigh, the pubic symphysis, or even the testicle on the affected side in men.

Pincer impingement can also manifest as posterior impingement, leading to pain in the buttock or sacroiliac region. This posterior hip pain can be challenging to differentiate from pain originating from the lower back or sacroiliac joint itself, highlighting the importance of thorough FAI diagnosis. Activities like fast walking or downhill walking, which involve repeated hip hyperextension, are common triggers for posterior impingement pain. In women, posterior hip pain during sexual intercourse is also a frequently reported symptom.

Mechanical symptoms like catching, clicking, or a sensation of the hip joint locking can accompany FAI, especially when labral tears are present. The duration of symptoms can vary significantly, and patients may sometimes recall a specific event that initiated their hip pain. A comprehensive understanding of symptom presentation is vital for effective FAI diagnosis.

Physical Examination: Key Tests for FAI Diagnosis

A physical examination is a cornerstone of FAI diagnosis. Observational gait analysis may reveal an antalgic gait (limping to reduce pain) or a Trendelenburg gait (pelvic drop due to weak hip abductors).

Limited hip range of motion is a significant finding in FAI. Internal rotation with the hip flexed to 90 degrees is typically markedly restricted. Flexion and abduction may also be limited, although these findings are less consistent than restricted internal rotation.

The hip impingement test is a highly sensitive and specific clinical test used in FAI diagnosis. This test is performed with the patient lying supine. The examiner flexes the patient’s hip and knee to 90 degrees, then progressively moves the hip from external rotation and abduction into internal rotation and adduction.

A positive impingement test is indicated by the elicitation of sudden, sharp pain in the hip, often described by patients as a reproduction of their typical hip symptoms. Studies have shown that a positive impingement test is present in over 90% of patients subsequently diagnosed with FAI, either radiologically or during surgery. Furthermore, this test has a high positive predictive value for labral pathology, making it a crucial component of FAI diagnosis.

Investigative Methods for FAI Diagnosis: Imaging Techniques

While clinical assessment is crucial, imaging plays a vital role in confirming FAI diagnosis and determining the extent of bony and soft tissue abnormalities.

Plain Radiography

Initial radiographic evaluation typically involves an anteroposterior (AP) pelvis radiograph combined with a cross-table lateral or Dunn view of the hip. These plain radiographs can reveal morphological abnormalities associated with FAI, as well as signs of degenerative changes like osteoarthritis. However, it’s important to recognize that radiographic evidence of FAI can be subtle, and radiographs may be reported as normal in some patients with FAI. Therefore, normal radiographs should not outweigh a strong clinical suspicion of FAI based on history and physical examination. Misdiagnosis of FAI as groin strain, low back pain, trochanteric bursitis, or early osteoarthritis is not uncommon when relying solely on initial radiographs.

Advanced Imaging: MRI and CT Scans

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), particularly MRI arthrography (MRA) with intra-articular contrast, is considered the gold standard imaging modality for FAI diagnosis. MRA provides detailed visualization of soft tissues, including the labrum and articular cartilage, allowing for accurate detection of labral tears and cartilage damage associated with FAI. Furthermore, intra-articular injection of local anesthetic and steroid at the time of MRA can be both diagnostically and therapeutically valuable, especially in cases with suspected early osteoarthritis. The anesthetic can help confirm the hip joint as the source of pain, while the steroid can provide temporary symptom relief.

Computed Tomography (CT) scans, especially with 3D reconstruction, are particularly useful in visualizing bony deformities associated with FAI. CT scans can provide detailed information about the shape and extent of cam and pincer lesions, aiding in preoperative planning for surgical management of complex FAI cases. While MRI excels in soft tissue evaluation, CT is superior for bony detail in FAI diagnosis.

Management Strategies Following FAI Diagnosis

Following FAI diagnosis, treatment strategies are tailored to the individual patient, considering symptom severity, activity level, and the extent of joint damage.

Non-Operative Management

Conservative, non-operative treatment is often the initial approach for managing FAI. This may involve activity modification to avoid extreme hip movements that provoke impingement symptoms. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can help manage pain and inflammation. Physical therapy plays a crucial role, particularly for pincer impingement. Sports therapy focused on improving core stability and promoting a more upright posture during activity can help modify dynamic hip flexion and reduce impingement.

Operative Interventions

Operative management is considered when non-operative treatments fail to provide adequate symptom relief and functional improvement. While FAI is recognized as a predisposing factor for osteoarthritis, current evidence does not definitively show that surgical intervention can alter the long-term course of osteoarthritis or eliminate the eventual need for hip replacement.

Arthroscopic Hip Surgery

Hip arthroscopy has become a popular surgical approach for FAI treatment due to its minimally invasive nature, leading to faster rehabilitation and a lower risk of complications compared to open surgery. Arthroscopy involves using small incisions and a camera to visualize and operate within the hip joint. During arthroscopy, labral tears can be repaired, and damaged cartilage can be addressed through debridement or regenerative techniques like microfracture. Osteochondroplasty, the surgical reshaping of bone, can be performed to address cam deformities by removing the bony bump at the femoral head-neck junction. Acetabular rim trimming can reshape the acetabulum in cases of pincer impingement, often with labral reattachment. While arthroscopy offers advantages, access to certain areas of the hip joint can be technically challenging. Potential complications include transient nerve injury (neuropraxia) and fluid extravasation.

Open Hip Dislocation Surgery

Open hip dislocation is a more invasive surgical approach that allows for comprehensive access to all areas of the hip joint, including the postero-inferior region, which can be difficult to reach arthroscopically. All procedures performed arthroscopically can also be performed via open hip dislocation. However, open surgery is a major procedure with a longer recovery period and a slightly higher complication rate compared to arthroscopy.

Conclusion: The Importance of Accurate FAI Diagnosis

FAI is a prevalent yet often underdiagnosed condition that can cause hip pain and contribute to degenerative hip disease. Accurate FAI diagnosis hinges on a careful patient history, a thorough physical examination (particularly the impingement test), and appropriate imaging studies. General practitioners play a critical role in recognizing and initiating the management of FAI.

The primary goals of FAI surgery are to alleviate symptoms and improve hip function in the short term. While growing evidence supports the effectiveness of surgery for these short-term goals, ongoing research is needed to determine if surgical intervention can modify the disease process and prevent or delay the onset of osteoarthritis in the long term. Early and precise FAI diagnosis is the first step towards effective management and improved patient outcomes.

References

[1] Griffin DR, Dickenson EJ, O’Donnell J, et al. The Warwick Agreement on femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI syndrome): an international consensus statement. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1169–76.

[2] Agricola R, Heijboer RR, Roze RH, et al. Cam impingement of the hip. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B:73–80.

[3] Nepple JJ, Kim YJ, Phillippon MJ, et al. Hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement in adolescents: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med 2012;40:217–23.

[4] Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, et al. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;417:112–20.

[5] Lequesne M, de Valois B, Rose-Pithon B, et al. Prevalence of radiologic hip osteoarthritis and symptomatic hip osteoarthritis in symptomatic individuals over 50 years of age: data from the French ESCEO study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004;12:484–92.

[6] Siebenrock KA, Schoeniger R, Werlen S, et al. Prevalence of cam-type deformities of the proximal femur in asymptomatic volunteers. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86-A:231–9.

[7] Reiman MP, Thorborg K. Clinical examination and physical assessment of hip joint-related pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2011;41:330–41.

[8] Kappe T, Ali KH, Gosvig KK, et al. Diagnostic value of hip provocation tests for anterior femoroacetabular impingement. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:199.

[9] Casartelli NC, Leunig M, Maffiuletti NA. Hip muscle strength and range of motion in symptomatic patients with femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:163–71.

[10] Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, et al. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87-B:1012–18.

[11] Larson CM, Giveans MR, Taylor MC. Complications after hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of the literature. Arthroscopy 2012;28:880–91.

[12] Philippon MJ, Maxwell RB, Johnston TL, et al. Open versus arthroscopic approach for femoroacetabular impingement: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:1427–35.