Gout, a form of inflammatory arthritis caused by the crystallization of uric acid within the joints, is becoming increasingly prevalent. Factors such as aging populations, rising obesity rates, and lifestyle modifications contribute to its growing incidence. As an automotive repair expert at xentrydiagnosis.store, understanding health conditions like gout, especially its diagnosis criteria, might seem outside our direct domain. However, recognizing the broader health context of our clients and workforce can enhance our overall service and workplace awareness. This article delves into the criteria for diagnosing gout, drawing from established medical research to provide a comprehensive understanding of this condition.

What is Gout and Why Understanding Diagnosis Matters?

Gout manifests when urate crystals deposit in joints, triggering an inflammatory response. While these crystals can also accumulate in soft tissues, they only cause inflammation when located within the joints. Historically recognized, gout, particularly when affecting the big toe (podagra), has been documented since ancient times. This crystal deposition occurs due to serum urate saturation, a byproduct of purine metabolism. Idiopathic gout, the most common form, often results from a genetic predisposition to reduced renal urate excretion. Numerous factors influence serum urate levels, as outlined in Box 1.

Typically, gout presents as a rapid-onset acute monoarthritis, frequently occurring at night. Commonly affected joints include the big toe, foot, ankle, knee, wrist, finger, and elbow, potentially due to urate’s propensity to crystallize in cooler body regions. Tophi, or crystal deposits, can also develop around hands, feet, elbows, and ears. Elderly individuals might experience oligoarticular or polyarticular gout, which can be less painful and affect osteoarthritic interphalangeal joints. Untreated gout typically resolves within 7 to 10 days. Following an initial attack, symptom-free periods may last months or years, but recurrence is common, leading to chronic tophaceous gout or permanent joint damage in some individuals. Radiologically, gout is characterized by subcortical cysts without erosions. Recurrence rates without urate-lowering treatment are high, with studies showing 62% recurrence after one year, 78% after two years, and 84% after three years following the first attack.

Summary Points:

- Acute gout is a common condition with increasing prevalence.

- Clinical diagnosis and treatment are typical for most acute gout cases.

- Lifestyle adjustments may play a role in reducing recurrent gout incidence.

- Careful evaluation of risks and benefits is crucial before prescribing gout treatments.

Who is at Risk of Gout and Hyperuricemia?

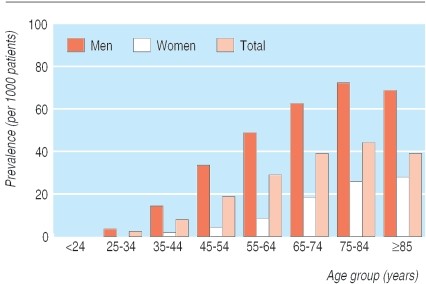

Gout prevalence is significant, with most studies indicating at least 1% of the population affected. In certain regions, such as New Zealand, prevalence rates are notably higher, reaching 3.6% in European populations and 6.4% in Maori populations. Gout is considerably more common in men, with women’s risk increasing post-menopause and in older age groups (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Prevalence of gout. Adapted from Mikuls et al.

Box 1: Factors Influencing Serum Urate Concentration

Factors that Decrease Serum Urate Concentration:

- Diet: Low-fat dairy products

- Drugs: Xanthine oxidase inhibitors (allopurinol, febuxostat), uricosuric drugs (sulfinpyrazone), uricase drugs (rasburicase), coumarin anticoagulants, and estrogens

Factors that Increase Serum Urate Concentration:

- Diet: Meat, fish, alcohol (especially beer and spirits), obesity, and weight gain

- Drugs: Diuretics, low-dose salicylates, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, cytotoxics, and lead poisoning

- Disease: Increased purine turnover (myeloproliferative and lymphoproliferative disorders, chronic hemolytic anemia, hemoglobinopathies, secondary polycythemia, thalassemia), increased purine synthesis (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, Lesch-Nyhan syndrome), reduced renal excretion (hypertension, hypothyroidism, sickle cell anemia, hyperparathyroidism, chronic renal disease)

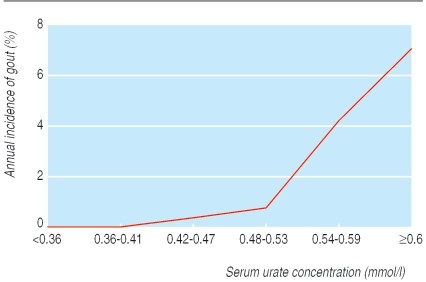

Gout development is directly linked to serum urate saturation, typically exceeding 0.42 mmol/l. This level is similar to the upper limit of many labs’ normal range for men, with lower normal ranges for premenopausal women. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia is widespread; a significant portion of the population has elevated serum urate levels, yet only a minority develop gout. Even with urate concentrations of 0.6 mmol/l or higher, the annual gout incidence remains relatively low (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Relation between serum urate concentration and annual incidence of gout. Adapted from Campion et al.

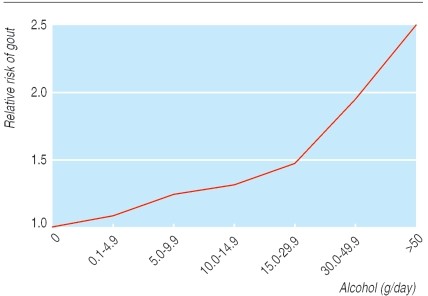

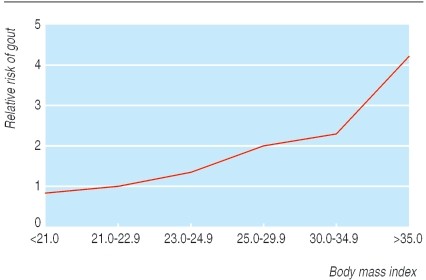

Lifestyle significantly impacts gout incidence. Studies on male health professionals have shown higher incidence among obese individuals or those with high alcohol intake (Figs 3 and 4). Beer consumption, more so than wine, increases gout risk, likely due to beer’s purine content, independent of alcohol. Higher meat and fish intake also elevates risk. Conversely, purine-rich vegetables show no effect, while low-fat dairy products appear protective, possibly due to the uricosuric effect of casein and lactalbumin (Table 1). Hyperuricemia is also linked to increased cardiovascular risk, potentially acting as an independent risk factor in high-risk individuals. Screening gout patients for cardiovascular risk factors is advisable, as studies have found high prevalences of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes among gout patients without prior cardiovascular disease diagnoses.

Fig 3. Effect of total alcohol intake on relative risk of first attack of gout. Adapted from Choi et al.

Fig 4. Effect of obesity on incidence of first attack of gout. Adapted from Choi et al.

Table 1: Effect of One Additional Daily Portion on First Attack of Gout

| Portion | Relative Risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Alcohol: | |

| Beer 335 ml | 1.49 (1.32 to 1.70) |

| Spirits 44 ml | 1.15 (1.04 to 1.28) |

| Wine 118 ml | 1.04 (0.88 to 1.22) |

| Food: | |

| Meat | 1.21 (1.04 to 1.41) |

| Seafood (fish)* | 1.07 (1.01 to 1.12) |

| Purine rich vegetables | 0.97 (0.79 to 1.19) |

| Total dairy products | 0.82 (0.75 to 0.90) |

| Low fat dairy products | 0.79 (0.71 to 0.87) |

| High fat dairy products | 0.99 (0.89 to 1.10) |

Data from health professionals follow-up study. *Calculated from weekly intake.

Gout Diagnosis Criteria: A Detailed Overview

The definitive method for diagnosing gout is identifying urate crystals in joint fluid. However, this invasive test is not routinely performed on all suspected gout cases. Clinical guidelines exist for diagnosing gout without joint aspiration (Box 2). It’s important to note that patients may not always meet these criteria at their initial presentation. In acute situations where gout is suspected, initiating treatment as if it were gout is often reasonable. Misdiagnosis and treatment of pseudogout or other inflammatory arthritis as gout is unlikely to cause harm. The critical differential diagnosis in acute settings is septic arthritis, which necessitates immediate joint aspiration and referral if suspected.

Serum urate levels might decrease during an acute gout attack, meaning a normal urate level at that time does not exclude gout. Table 2 summarizes further investigations considered for suspected gout patients.

Box 2: American College of Rheumatology Preliminary Criteria for the Clinical Diagnosis of Gout

Six or more of these criteria are required for a gout diagnosis:

- More than one attack of acute arthritis

- Maximum inflammation developed within one day

- Attack of monoarthritis

- Redness over joints

- Painful or swollen first metatarsophalangeal joint

- Unilateral attack on first metatarsophalangeal joint

- Unilateral attack on tarsal joint

- Tophus (proved or suspected)

- Hyperuricemia

- Asymmetric swelling within a joint on radiograph

- Subcortical cysts without erosions on radiograph

- Joint fluid culture negative for organisms during attack

Clinical Gout Diagnosis Criteria Explained

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria, detailed in Box 2, offer a structured approach to clinically diagnosing gout. These criteria are preliminary but widely used and valuable in guiding diagnosis, especially when joint aspiration is not feasible or immediately available. For a diagnosis of gout based on these criteria, a patient must present with six or more of the listed conditions. Let’s break down each criterion to understand its significance in gout diagnosis:

- More than one attack of acute arthritis: Recurrent episodes of joint inflammation are a hallmark of gout. While a first-time attack might raise suspicion, multiple attacks strengthen the likelihood of gout.

- Maximum inflammation developed within one day: Gout attacks are known for their rapid onset and intensification. Reaching peak inflammation within 24 hours is a characteristic feature, differentiating gout from other arthritic conditions that might develop more slowly.

- Attack of monoarthritis: Gout frequently affects a single joint, particularly at the onset. This monoarticular presentation is a key diagnostic clue, although gout can become polyarticular over time.

- Redness over joints: Inflammation in gout often leads to visible redness (erythema) around the affected joint. This is a classic sign of inflammatory arthritis, including gout.

- Painful or swollen first metatarsophalangeal joint: The big toe (first metatarsophalangeal joint) is the most commonly affected site in gout, known as podagra. Pain and swelling in this joint are highly suggestive of gout.

- Unilateral attack on first metatarsophalangeal joint: Gout attacks typically start in one big toe. Unilateral involvement, meaning only one side is affected initially, is more characteristic of gout in the early stages.

- Unilateral attack on tarsal joint: Similar to the big toe, the tarsal joints in the ankle and foot can be initial sites of gout. A unilateral attack in these joints adds to the diagnostic probability.

- Tophus (proved or suspected): Tophi are deposits of urate crystals that form nodules under the skin around joints and other areas. The presence of tophi, whether confirmed by biopsy or strongly suspected clinically, is a very specific sign of gout, indicating chronic urate deposition.

- Hyperuricemia: Elevated serum urate levels are a prerequisite for gout. While not all individuals with hyperuricemia develop gout, it is a necessary underlying condition. However, it’s important to remember that serum urate levels can be normal during an acute gout attack, which is why this criterion alone is not definitive.

- Asymmetric swelling within a joint on radiograph: In chronic gout, radiographic findings can include asymmetric joint swelling. This asymmetry helps distinguish gout from other forms of arthritis that might present with more symmetric joint involvement.

- Subcortical cysts without erosions on radiograph: Radiographic imaging in chronic gout often reveals subcortical cysts (fluid-filled sacs near the bone surface) without bony erosions. This is a characteristic, though not always present, finding in long-standing gout.

- Joint fluid culture negative for organisms during attack: Ruling out septic arthritis is crucial in the differential diagnosis of acute joint pain. A negative joint fluid culture for bacteria or other organisms helps exclude infection, making gout a more likely diagnosis in the context of other criteria.

These criteria are designed to be used in combination, with a score of six or more increasing the likelihood of gout. Clinicians use these criteria alongside their clinical judgment, patient history, and other investigations to reach an accurate diagnosis.

Table 2: Investigations to Consider for Patients with Gout

| Test | Comment |

|---|---|

| Serum urate concentration | Level may decrease during an acute attack |

| Full blood count | To exclude myeloproliferative disorders; raised white cell count may indicate septic arthritis |

| Renal function | Hyperuricemia can occur in renal failure; adjust allopurinol dose |

| Fasting lipids, glucose, and thyroid function | Hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypothyroidism, and possibly hyperthyroidism are associated with gout |

| Urinary urate excretion | Uricosurics are contraindicated in patients with high urinary urate excretion. Measurement advised if serum urate concentration is >0.8 mmol/l due to renal stone risk |

Treatment and Prevention Strategies for Gout

Few definitive studies guide acute gout treatment. Treatment choices are based on balancing risks and benefits.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs):

NSAIDs, particularly indomethacin, are commonly used for acute gout. However, high-quality placebo-controlled trials are limited. Studies comparing different NSAIDs show no significant outcome differences. Trials indicate similar clinical outcomes between indomethacin and etoricoxib (a COX-2 inhibitor). Gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risks associated with NSAIDs are well-known and significant, especially in gout patients who may already be at higher risk for such side effects.

Colchicine:

Colchicine is a popular acute gout treatment in some regions. While effective against placebo, a trial showed high rates of diarrhea and vomiting in the colchicine group, often before pain relief. Lower doses of colchicine (e.g., 0.5 mg every eight hours) may be more effective and less toxic than the traditionally advised higher doses (up to 6 mg). Intravenous colchicine is considered too toxic for routine use.

Steroids and Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH):

Oral, parenteral, intra-articular steroids, and ACTH are used for acute gout. Placebo-controlled trials are lacking. Short courses of oral steroids may be preferable to NSAIDs or colchicine due to fewer adverse events.

Local Treatments:

Elevation, rest, and ice application are traditional gout treatments. A small trial suggested ice application benefits. Clinical experience supports these approaches. Treatment choice should consider adverse event risks and patient preferences. For high-risk patients, rest, cooling, and strong analgesics may be preferable to specific gout medications.

Prevention of Recurrent Gout:

Data on preventing recurrent gout are limited. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia generally doesn’t require treatment, except in specific cases like malignancy treatment or very high urate concentrations with high renal excretion to prevent kidney stones. Routine hyperuricemia screening is not typically recommended. Nevertheless, many allopurinol prescriptions are issued without a recorded gout diagnosis.

Box 3: Suggested Quality Care Indicators for Gout Management (Adapted from Mikuls et al.)

Treatment of Acute Gout:

- For acute gouty arthritis patients without significant renal impairment or peptic ulcer disease, treatment options include:

- NSAIDs

- ACTH or steroids (systemic or intra-articular)

- Colchicine

Prevention of Recurrent Gout:

- Obese gout patients or those with high alcohol intake should be advised to lose weight and/or reduce alcohol consumption.

- Initiate allopurinol at low doses in patients with major renal impairment.

- Reduce azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine dose by at least 50% when co-prescribing with xanthine oxidase inhibitors.

- Co-prescribe NSAIDs or colchicine for the first three months of urate-lowering treatment to prevent rebound gout attacks, unless contraindicated.

- Asymptomatic hyperuricemia does not require treatment.

- Avoid uricosuric drugs in patients with significant renal impairment or a history of renal stones.

- Offer urate-lowering treatment to patients with tophi, radiographic erosions, or more than two attacks per year.

- Check serum urate levels in patients on xanthine oxidase inhibitors at least once in the first six months.

- Monitor full blood count and creatine kinase every six months in patients on long-term prophylactic colchicine with major renal impairment.

Elevated serum urate and recurrent joint pain alone are insufficient for gout diagnosis. Careful consideration is needed before starting lifelong prophylactic drug treatment due to potential side effects. Treatment benefit should be assessed, and diagnosis reviewed if ineffective.

For occasional gout attacks, prophylactic treatment risks may outweigh benefits. Patient preferences are crucial in deciding on prophylactic drugs, which should be offered to those with frequent attacks (more than two yearly), tophi, or radiographic changes. Urate-lowering drugs should not be started during acute attacks. Unless contraindicated, prophylactic colchicine or NSAIDs should be prescribed for the first three months of urate-lowering treatment to prevent rebound gout flares. Colchicine prophylaxis has been shown to reduce rebound gout incidence during allopurinol initiation.

Tips for Non-Specialists:

- Serum urate levels can decrease during a gout attack.

- Oral steroids may be a safer acute gout treatment alternative to NSAIDs or colchicine.

- Urate-lowering drugs are typically needed only for frequent gout attacks.

- Asymptomatic hyperuricemia does not require treatment.

The goal of serum urate reduction is to lower levels below 0.36 mmol/l, preventing urate crystallization and mobilizing existing deposits. Even if this target isn’t reached, any urate reduction can decrease recurrent gout incidence.

Medication Review:

Certain medications, especially diuretics, can induce hyperuricemia. Reviewing and potentially stopping urate-raising drugs is advisable.

Lifestyle Modifications:

Controlled trials on lifestyle changes for recurrent gout prevention are lacking. Traditional low-purine diets are poorly adhered to and not generally recommended. However, health professional studies suggest simple changes may impact recurrent gout incidence:

- Weight loss

- Reduced meat or fish intake

- Wine instead of beer

- Daily skimmed milk

Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors:

Allopurinol has been a primary gout prevention medication since the 1960s. Placebo-controlled trials demonstrating its effect on recurrent gout are lacking, but extensive clinical experience confirms its effectiveness. However, trials of febuxostat, a newer xanthine oxidase inhibitor, showed that only a minority of patients on allopurinol reached target urate levels (<0.36 mmol/l). Allopurinol doses should be titrated up to 900 mg/day if needed to achieve target urate levels. Allopurinol intolerance and hypersensitivity syndrome are potential concerns, particularly in patients with renal impairment, who should receive lower doses (≤300 mg daily).

Febuxostat is a more recent option, shown in trials to be more effective than allopurinol in achieving target urate levels but without a demonstrated reduction in acute gout attacks compared to allopurinol. It may be beneficial for allopurinol-intolerant patients.

Uricosurics:

Sulfinpyrazone is a uricosuric drug available in some regions. It increases renal urate excretion, raising kidney stone risk, and is unsuitable for patients with renal impairment or high urinary urate excretion. Long-term efficacy data are limited.

Colchicine:

Controlled trials on colchicine alone for recurrent gout prevention are lacking. However, its effectiveness in reducing rebound attacks during allopurinol initiation indirectly supports its long-term preventive potential.

NSAIDs:

Long-term NSAID use for recurrent gout prevention is sometimes practiced, but controlled trial data are lacking.

Other Urate-Lowering Drugs:

Losartan and flubiprofen may reduce serum urate, but controlled trial data on their use in preventing recurrent gout are not available.

Conclusion: Advancing Gout Management

Recent years have seen renewed interest in improving gout diagnosis and management. New epidemiological data, systematic reviews of treatment evidence, evidence-based quality indicators, high-quality controlled trials, and new gout-specific drugs are emerging. Uricase drugs are available for specific indications and may become more broadly accessible for intractable gout cases.

Additional Educational Resources:

- Clinical Evidence: Review of evidence for gout treatment and prevention.

- Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin: Review of primary care gout management.

- Evidence Based Rheumatology: Book chapter on evidence-based gout treatment.

Information for Patients:

- Arthritis Research Campaign (UK): Patient information booklet.

- UK Gout Society: Charity providing information and campaigning for improved gout management.

Ongoing Research:

- Trials comparing COX-2 inhibitors with indomethacin for acute gout.

- Studies on pegylated recombinant mammalian uricase.

- Long-term safety studies of febuxostat.

Unanswered Research Questions:

- Comparative effectiveness of NSAIDs and prednisolone for acute gout versus placebo.

- Effectiveness of simple lifestyle changes in gout prevention.

- Allopurinol effectiveness in preventing gout in different patient groups.

References

[1] Roddy E, Choi HK. Epidemiology of gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(6):216.

[2] Schlesinger N, Schumacher HR Jr. Gout: evidence-based management. J Clin Rheumatol. 2003 Oct;9(5 Suppl):S27-35.

[3] van Echteld IA, van Roon EN, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Colchicine for acute gout. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Dec 15;55(6):955-62.

[4] Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977 Aug;20(5):895-900.

[5] Mikuls TR, Farrar JT, Bilker WB, et al. Gout epidemiology: results from the UK General Practice Research Database, 1990-1999. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005 Oct;64(10):1426-31.

[6] Saag KG, Choi H. Epidemiology, risk factors, and lifestyle modifications for gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8 Suppl 1:S2.

[7] Scragg R, Khaw KT, Murphy S. Serum urate and gout in participants in the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1996 Sep 15;144(6):538-45.

[8] Campion EW, Glynn RJ, deLabry ME, et al. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Risks and consequences in the Normative Aging Study. Am J Med. 1987 Dec;82(6):421-6.

[9] Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, et al. Alcohol intake and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Lancet. 2004 Apr 10;363(9417):1277-81.

[10] Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, et al. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Jun 13;165(14):1642-8.

[11] Choi HK, Willett W, Curhan G. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med. 2004 Mar 11;350(11):1093-103.

[12] Krishnan E, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Hyperuricemia and incident hypertension among men without metabolic syndrome. Hypertension. 2007 Feb;49(2):298-303.

[13] Hak AE, Choi HK. Hyperuricemia and cardiovascular disease risk. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(2):205.

[14] Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977 Aug;20(5):895-900.

[15] Choi HK, Seeger JD. Thyroid hormone deficiency and hyperuricemia: a potential causal association. J Rheumatol. 2006 Aug;33(8):1637-41.

[16] Schlesinger N. Diagnosis of gout: recent advances. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014 Jan;26(1):82-8.

[17] Doherty M, Schlesinger N, Dalbeth N, et al. 2017 revised EULAR evidence-based recommendations for gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Sep;76(9):1467-1479.

[18] Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Jan;76(1):29-42.

[19] Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Bennett K, et al. High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early gout flare: twenty-four-hour outcome of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Aug;62(8):2225-32.

[20] Zhang W, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part 1: diagnosis. Report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Oct;65(10):1301-11.

[21] Mikuls TR, Johnson RJ, Kerin KD, et al. Quality of care indicators for gout management. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Feb 15;54(2):529-39.

[22] Khanna PP, Valeriano J, Seth R, et al. Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gout. Ann Intern Med. 2012 May 1;156(11):777-80.

[23] Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005 Dec 8;353(23):2450-61.

[24] Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Wortmann RL, et al. Effects of febuxostat versus allopurinol and placebo in reducing serum urate in patients with hyperuricemia and gout: a 28-week, phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Sep 15;59(9):1223-32.

[25] Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Espinoza LR, et al. Febuxostat versus allopurinol in patients with gout: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Apr;62(4):1056-66.