Hemophilia is a rare inherited bleeding disorder that impairs the blood’s ability to clot, leading to prolonged bleeding after injury, surgery, or even spontaneously. This condition, primarily affecting males, varies in severity depending on the deficiency level of specific clotting factors, notably factor VIII in hemophilia A and factor IX in hemophilia B. Effective nursing care is paramount in managing hemophilia, focusing on early diagnosis, preventing bleeding episodes, managing complications, and enhancing the quality of life for affected individuals. Understanding the nuances of Hemophilia Nursing Diagnosis is crucial for healthcare professionals to deliver optimal patient care.

Understanding Hemophilia: Types and Pathophysiology

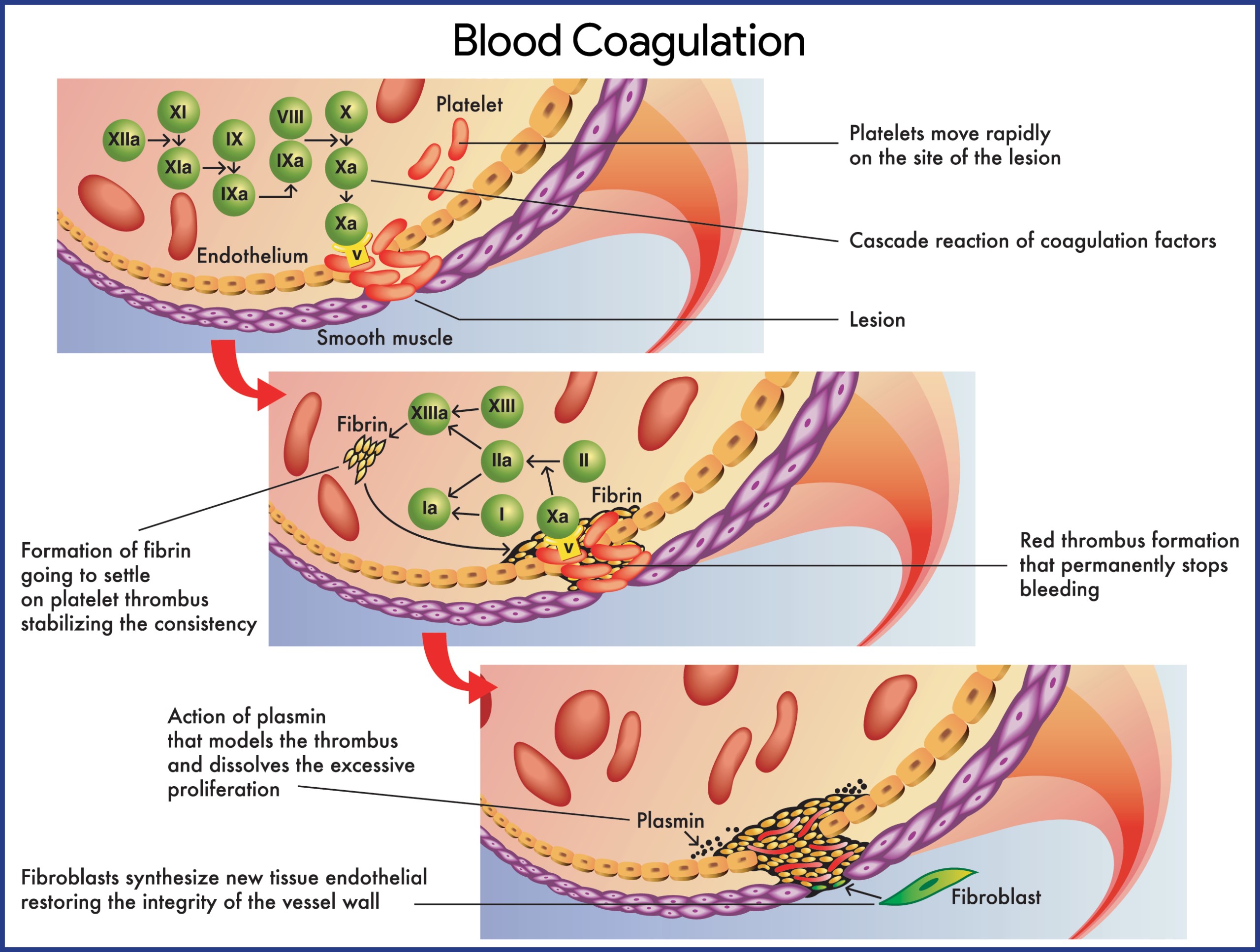

Hemophilia is not a singular disease but encompasses different types, primarily classified by the deficient clotting factor. Hemophilia A, the most common form, results from a deficiency in factor VIII, while hemophilia B (Christmas disease) is caused by a deficiency in factor IX. Both factors are essential components of the coagulation cascade, the body’s intricate system to stop bleeding.

Pathophysiology of Hemophilia A and B

Hemophilia A: The underlying issue in hemophilia A is a quantitative or qualitative defect in factor VIII (FVIII). Normally produced in the liver’s vascular endothelium and reticuloendothelial system, FVIII plays a critical role in the intrinsic coagulation pathway. A deficiency or dysfunction of FVIII disrupts this pathway, preventing the formation of stable blood clots. This leads to excessive bleeding, ranging from prolonged bleeding after minor injuries to spontaneous hemorrhages, particularly into joints and muscles. Interestingly, synovial cells in joints produce tissue factor pathway inhibitor, which further inhibits factor Xa, potentially explaining why hemophilic joints are prone to bleeding. This localized environment may also contribute to the effectiveness of activated factor VII (FVIIa) in treating acute joint bleeds (hemarthroses). Recurrent bleeding into a joint can cause synovial inflammation, creating a “target joint” vulnerable to future bleeds. A significant complication in about 30% of severe hemophilia A cases is the development of alloantibody inhibitors against FVIII. These IgG antibodies neutralize replacement therapy, complicating treatment.

Hemophilia B: Hemophilia B arises from a deficiency or dysfunction in factor IX (FIX), or the presence of factor IX inhibitors. Similar to hemophilia A, this disrupts the intrinsic coagulation cascade, leading to both spontaneous and trauma-induced hemorrhages. Bleeding can occur in various sites, including joints (knees, elbows), muscles, the central nervous system (CNS), gastrointestinal (GI) system, genitourinary (GU) system, pulmonary system, and cardiovascular system. Factor IX, a vitamin K-dependent glycoprotein synthesized in the liver, is activated in the coagulation cascade. The intrinsic pathway initiates with factor XII activation by damaged endothelium, while the extrinsic pathway involves tissue factor, factor VII, and calcium ions to activate factor X. Factors VIII and IX, when activated, work together to activate factor X, a key enzyme in converting fibrinogen to fibrin, the protein meshwork of a blood clot. The absence of either factor significantly impairs clot formation and results in clinical bleeding.

Hemophilia Statistics and Prevalence

Hemophilia, while rare, has a global presence. Hemophilia A is the most common X-linked genetic disorder and the second most prevalent factor deficiency after von Willebrand disease. Globally, hemophilia A occurs in approximately 1 in 5,000 male births. Notably, about one-third of individuals with hemophilia A have no family history, suggesting spontaneous genetic mutations. In the United States, the prevalence is around 20.6 cases per 100,000 males, with an estimated 20,000 people affected in 2016. Hemophilia A affects all races and ethnicities equally. As an X-linked recessive condition, it predominantly affects males, while females are typically asymptomatic carriers. Hemophilia B is less common, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 25,000 to 30,000 male births and a prevalence of 5.3 cases per 100,000 males. Severe hemophilia B accounts for 44% of these cases. Overall, hemophilia A constitutes 80-85% of all hemophilia cases, hemophilia B about 14%, and other clotting disorders make up the remainder. Hemophilia B also occurs across all racial and ethnic groups.

Genetic Causes of Hemophilia

Hemophilia A and B are primarily genetic disorders. Hemophilia is famously known as ‘the royal disease’ due to its prevalence in European royal families, traced back to Queen Victoria.

Genetics: Hemophilia A is caused by inherited or spontaneous genetic mutations in the F8 gene, leading to deficient or dysfunctional factor VIII. Acquired hemophilia A can also occur due to the development of inhibitors against factor VIII. Hemophilia B is also an X-linked recessive disorder, resulting from mutations in the F9 gene that codes for factor IX. Similar to hemophilia A, acquired hemophilia B can result from factor IX inhibitors, though this is less common.

Clinical Manifestations of Hemophilia

Clinical presentation of hemophilia varies widely based on the severity of factor deficiency. A history of bleeding disproportionate to injury, spontaneous bleeding, or a family history of bleeding disorders should raise suspicion for hemophilia.

Spontaneous Hemorrhage: Neonatal bleeding manifestations are common in severe hemophilia, affecting 30-50% of patients. This can present as prolonged bleeding after circumcision, severe hematomas, or bleeding from the umbilical cord, blood draw sites, or immunization sites.

Hematuria: Gross hematuria (blood in urine) is a frequent symptom, occurring in up to 90% of patients, indicating bleeding within the genitourinary tract.

General Symptoms: Weakness and orthostatic hypotension (lightheadedness upon standing) can occur due to blood loss.

Musculoskeletal Bleeding: Musculoskeletal bleeds, particularly into joints (hemarthrosis), are hallmark symptoms. Children may present with tingling, cracking sensations, warmth, pain, stiffness, and reluctance to use the affected joint. Recurrent hemarthroses can lead to chronic joint damage and hemophilic arthropathy.

Central Nervous System (CNS) Bleeding: CNS bleeds are life-threatening complications. Symptoms include headache, stiff neck, vomiting, lethargy, irritability, and signs of spinal cord compression or syndromes.

Genitourinary and Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Bleeding in these areas can manifest with painless hematuria or gastrointestinal bleeding with potential abdominal tenderness and peritoneal signs.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings for Hemophilia

Diagnosing hemophilia involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing.

Laboratory Studies:

- Coagulation Studies: Initial screening tests include prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). In hemophilia, aPTT is typically prolonged, while PT is usually normal.

- Factor Assays: Specific factor assays are crucial to confirm the diagnosis and determine the type and severity of hemophilia. Factor VIII assay is used for hemophilia A, and factor IX assay for hemophilia B. The level of factor activity correlates with disease severity:

- Severe hemophilia: <1% factor activity

- Moderate hemophilia: 1-5% factor activity

- Mild hemophilia: 5-40% factor activity

- Chromogenic Assay: This assay measures plasma factor VIII activity and is considered more accurate by some, although it’s less widely available.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Used to assess for anemia secondary to blood loss.

Imaging Studies:

- CT Scans: Head CT scans without contrast are used to detect intracranial hemorrhage, either spontaneous or trauma-related.

- MRI: MRI of the head and spinal cord provides more detailed assessment of hemorrhage and is also valuable in evaluating joint damage, cartilage, synovium, and joint space in chronic hemarthropathy.

- Ultrasonography: Joint ultrasonography is useful for evaluating acute and chronic joint effusions.

- Radiography: X-rays are less helpful in acute hemarthrosis but can detect chronic degenerative joint disease in patients with recurrent joint bleeds or inadequate treatment.

Inhibitor Testing: If bleeding is not controlled with factor replacement, inhibitor testing is necessary to detect antibodies against factor VIII or IX.

Carrier Testing: For females with a family history of hemophilia, carrier testing can be performed by measuring the ratio of factor VIII coagulant activity to von Willebrand factor (vWF) antigen. A ratio <0.7 suggests carrier status. Genetic testing can also identify carriers and diagnose hemophilia prenatally.

Medical Management of Hemophilia

Hemophilia management is multifaceted, aiming to prevent bleeding, treat acute bleeds, manage complications, and improve patient quality of life.

Prehospital and Emergency Department Care: Rapid transport to a specialized hemophilia treatment center is crucial. Prehospital care focuses on aggressive hemostatic techniques and assisting patients with self-administered factor therapy if possible. In the emergency department, immediate correction of coagulopathy is paramount, even before complete diagnostic workup. Life-threatening bleeds require immediate factor replacement to achieve approximately 100% factor levels initially.

Factor Replacement Therapy: The cornerstone of hemophilia treatment is factor replacement therapy using concentrates of factor VIII for hemophilia A and factor IX for hemophilia B.

- Factor Concentrates: Recombinant factor concentrates are preferred due to their higher safety profile (reduced risk of blood-borne infections). Continuous infusion can improve hemostasis and reduce the total factor dose needed. Factor level assays are essential to guide dosing and frequency of infusions.

- Desmopressin (DDAVP): For mild hemophilia A, DDAVP, a vasopressin analog, can be effective. It stimulates a transient increase in endogenous factor VIII levels, sufficient for minor bleeds or procedures.

Management of Bleeding Episodes:

- RICE Therapy: Rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) are crucial initial measures for joint and muscle bleeds. Immobilization and ice packs reduce swelling and pain.

- Prompt Factor Infusion: Early factor infusion at the first signs of a bleed can often prevent progression and the need for repeated infusions.

Treatment of Patients with Inhibitors: Managing patients with inhibitors is challenging.

- High-dose Factor VIII: Low-titer inhibitors may be overcome with high doses of factor VIII.

- Bypassing Agents: For high-titer inhibitors, bypassing agents like activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC) or recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa) are used to promote clot formation through alternative pathways.

- Immune Tolerance Induction (ITI): ITI is a long-term strategy to eliminate inhibitors by regularly administering high doses of factor concentrate.

Prophylactic Factor Infusions: Regular prophylactic factor infusions are the standard of care, especially for severe hemophilia, to prevent spontaneous bleeds and joint damage. Prophylaxis significantly reduces bleeding frequency and improves long-term joint health.

Pain Management: Chronic hemophilic arthropathy leads to chronic pain.

- Non-narcotic Analgesics: NSAIDs can be used for acute and chronic arthritic pain, but aspirin should be avoided due to its irreversible antiplatelet effects.

- Narcotic Analgesics: Used cautiously for severe pain, but long-term use carries addiction risks.

- Physical Therapy: Crucial for maintaining joint function and mobility.

Activity and Lifestyle Modifications: While high-impact contact sports should be avoided, appropriate physical activity is encouraged to improve muscle strength, joint health, and psychosocial well-being.

Gene Therapy: Gene therapy for hemophilia is an evolving field with promising results. Different approaches include ex vivo, in vivo, and nonautologous gene therapy to deliver the missing clotting factor gene.

Radiosynovectomy: For recurrent synovitis from joint bleeds, radiosynovectomy (intra-articular injection of radioisotopes) can reduce bleeding and slow joint damage progression.

Pharmacologic Management in Detail

- Factor VIII Concentrates (e.g., Recombinant FVIII): First-line treatment for hemophilia A, used for acute bleeds and prophylaxis.

- Factor IX Concentrates (e.g., Recombinant FIX): First-line treatment for hemophilia B, used for acute bleeds and prophylaxis.

- Antifibrinolytic Agents (e.g., Tranexamic Acid, Aminocaproic Acid): Useful for mucosal bleeds (e.g., oral bleeds) but contraindicated in hematuria from the upper urinary tract due to the risk of urinary obstruction.

- Coagulation Factor VIIa (Recombinant): Bypassing agent used in patients with inhibitors.

- Antihemophilic Agents: Broad category encompassing factor concentrates and bypassing agents.

- Monoclonal Antibodies (e.g., Emicizumab): A bispecific antibody that mimics the cofactor function of factor VIII, used for prophylaxis in hemophilia A with and without inhibitors.

- Vasopressin Analogs (Desmopressin): For mild hemophilia A to transiently increase factor VIII levels.

Hemophilia Nursing Management: A Patient-Centered Approach

Nursing care is integral to hemophilia management, focusing on patient education, preventing complications, and providing holistic support.

Nursing Assessment in Hemophilia

A comprehensive nursing assessment is crucial for identifying and managing hemophilia effectively.

- History: Obtain a detailed history, including:

- History of bleeding disproportionate to trauma.

- Spontaneous bleeding episodes.

- Family history of bleeding disorders.

- Concomitant illnesses, especially those associated with acquired hemophilia (autoimmune disorders, malignancies, allergic reactions).

- Medication history, including aspirin or NSAID use.

- Physical Examination:

- Musculoskeletal Assessment: Assess for joint swelling, warmth, pain, limited range of motion (ROM), contractures, and bony changes indicative of hemarthropathy.

- Skin Assessment: Look for bruising, hematomas, petechiae, and signs of bleeding.

- Neurological Assessment: Assess for signs of intracranial hemorrhage (headache, stiff neck, vomiting, altered mental status).

- Vital Signs: Monitor for signs of blood loss (tachycardia, hypotension).

Hemophilia Nursing Diagnoses

Based on the assessment data, common nursing diagnoses for patients with hemophilia include:

- Risk for Bleeding related to deficiency of clotting factors (factor VIII or factor IX). This is the primary nursing diagnosis in hemophilia.

- Acute Pain related to hemarthrosis, muscle bleeds, or traumatic injuries.

- Impaired Physical Mobility related to joint pain, swelling, and muscle weakness secondary to hemarthrosis and bleeding episodes.

- Risk for Injury related to bleeding tendencies and potential for trauma.

- Deficient Knowledge related to hemophilia management, treatment, and prevention strategies.

- Compromised Family Coping related to the chronic nature of hemophilia and the challenges of managing the condition.

- Anxiety related to unpredictable bleeding episodes and the chronic nature of the condition.

Nursing Care Planning and Goals for Hemophilia

The overarching goals of nursing care for patients with hemophilia are:

- Prevent and minimize bleeding episodes.

- Manage pain effectively.

- Maintain optimal physical mobility and function.

- Promote patient and family coping and adaptation to the chronic condition.

- Increase patient and family knowledge about hemophilia and its management.

- Prevent complications associated with hemophilia and its treatment.

Nursing Interventions for Hemophilia

Nursing interventions are tailored to address the specific nursing diagnoses and patient needs.

For Risk for Bleeding:

- Administer Factor Replacement Therapy: Administer factor VIII or IX concentrates as prescribed, ensuring proper dosage and timing. Educate patients and families on self-infusion techniques.

- Monitor for Bleeding: Regularly assess for signs and symptoms of bleeding (bruising, hematomas, joint swelling, hematuria, gastrointestinal bleeding, CNS bleeding).

- Implement Bleeding Precautions: Educate patients and families on strategies to minimize trauma and prevent bleeding:

- Avoidance of contact sports and high-risk activities.

- Safe home environment to prevent falls and injuries.

- Use of protective gear during activities.

- Caution with procedures that may cause bleeding (injections, dental work).

- Educate on Early Recognition of Bleeding: Teach patients and families to recognize early signs of bleeding and initiate prompt treatment.

For Acute Pain:

- Pain Assessment: Regularly assess pain using appropriate pain scales.

- Pain Management Strategies:

- Administer prescribed analgesics (non-narcotic and narcotic) as needed.

- Implement non-pharmacological pain relief measures: RICE therapy, positioning, splinting, distraction, relaxation techniques.

- Monitor Pain Relief Effectiveness: Evaluate the effectiveness of pain management interventions and adjust as needed.

For Impaired Physical Mobility:

- Assess Mobility: Evaluate joint ROM, muscle strength, and functional mobility.

- Promote Physical Therapy: Encourage participation in physical therapy to maintain joint function, muscle strength, and prevent contractures.

- Encourage Active ROM Exercises: Teach and encourage patients to perform active ROM exercises within their pain tolerance.

- Assistive Devices: Recommend and assist with the use of assistive devices (e.g., crutches, braces) as needed.

For Risk for Injury:

- Safety Education: Educate patients and families on injury prevention strategies at home, school, and during activities.

- Home Safety Assessment: Assess the home environment for potential hazards and recommend modifications.

For Deficient Knowledge:

- Patient and Family Education: Provide comprehensive education about hemophilia:

- Nature of the disease, inheritance pattern.

- Types of hemophilia and factor deficiencies.

- Signs and symptoms of bleeding.

- Factor replacement therapy: administration, dosage, frequency, storage.

- Prophylaxis regimens.

- Bleeding precautions and injury prevention.

- Importance of regular medical follow-up and hemophilia treatment center care.

- Emergency protocols for bleeding episodes.

- Resources and support organizations.

For Compromised Family Coping and Anxiety:

- Emotional Support: Provide emotional support to patients and families.

- Assess Coping Mechanisms: Assess family coping strategies and identify areas needing support.

- Referral to Support Services: Connect families with social workers, support groups, and hemophilia organizations.

- Address Anxiety: Provide reassurance, education, and coping strategies to manage anxiety related to hemophilia.

Evaluation of Nursing Care

Nursing care is evaluated based on the achievement of patient goals. Expected outcomes include:

- Patient experiences a reduction in bleeding episodes or effectively manages bleeding when it occurs.

- Patient achieves adequate pain control.

- Patient maintains optimal physical mobility and functional abilities.

- Patient and family demonstrate effective coping mechanisms and adaptation to hemophilia.

- Patient and family demonstrate increased knowledge about hemophilia and its management.

- Patient remains free from complications related to hemophilia and its treatment.

Documentation Guidelines

Accurate and thorough documentation is essential in hemophilia nursing care. Documentation should include:

- Baseline and ongoing assessment findings, including signs and symptoms of bleeding, pain assessments, and mobility status.

- Individual patient and family preferences and cultural/religious considerations.

- Nursing care plan and individuals involved in care.

- Patient and family education provided and their understanding.

- Patient responses to treatments, interventions, and factor infusions.

- Progress towards desired outcomes and goal achievement.

- Long-term care needs and responsible parties for follow-up actions.

By understanding hemophilia nursing diagnosis and implementing comprehensive, patient-centered care, nurses play a vital role in improving the lives of individuals with hemophilia, minimizing bleeding episodes, managing pain and complications, and empowering patients and families to live full and active lives.