Introduction to Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation (IBS-C)

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a prevalent and complex functional gastrointestinal disorder encountered frequently in clinical settings. Within the spectrum of IBS, the constipation-predominant subtype, known as IBS-C, represents a significant portion, affecting over a third of all diagnosed IBS cases. Accurate Ibs C Diagnosis is crucial for effective patient management and requires a nuanced, patient-centered approach. This involves a detailed clinical history, judicious use of targeted investigations, and consistent follow-up care. Leading IBS organizations and medical guidelines advocate for a positive diagnosis of IBS based primarily on the patient’s reported symptoms. The hallmark symptom of IBS is abdominal pain, which may or may not be relieved by bowel movements. Distension and bloating are also commonly reported symptoms. It is paramount to carefully evaluate for any alarm symptoms before confirming an ibs c diagnosis. For patients with moderate to severe IBS-C, pharmacotherapy with linaclotide is a recommended treatment option, supported by robust evidence from randomized controlled trials. However, it’s important to consider that diarrhea is a potential side effect of linaclotide, and comprehensive cost-effectiveness data are still emerging.

Understanding Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is defined as a chronic functional gastrointestinal condition, widely observed in everyday clinical practice. More precisely, it’s categorized as a functional bowel disorder believed to stem from disruptions in the intricate gut-brain interaction.1 Although IBS patients often present with diverse symptom profiles, the unifying characteristic is abdominal pain or discomfort, frequently, but not always, alleviated by defecation. Over the past few decades, numerous clinical guidelines, consensus statements, and position papers have been developed to define and refine the diagnostic criteria for IBS.2–4 This article aims to provide a concise overview of the epidemiology, ibs c diagnosis, and management strategies relevant to primary care, with a particular focus on IBS-C and the pharmacological intervention using linaclotide, a pioneering guanylate cyclase inhibitor.

The most recognized and widely utilized diagnostic framework for IBS is the Rome criteria, which have undergone several revisions since their initial introduction,4,5 culminating in the Rome IV criteria in 2016.6 Rome IV defines IBS as a functional bowel disorder characterized by recurrent abdominal pain occurring at least once a week in the preceding three months, associated with two or more of the following: pain related to defecation, pain linked to changes in stool frequency, and pain associated with changes in stool form (appearance). These symptoms must have been present for at least three months, with symptom onset at least six months prior to the ibs c diagnosis.7 Based on predominant bowel habits, Rome IV classifies IBS into four primary subtypes: IBS with predominant constipation (IBS-C), IBS with predominant diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with mixed bowel habits (IBS-M), and unclassified IBS (IBS-U). The determination of predominant bowel habit relies on the quantification of stool consistency (appearance), typically assessed using the Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS)8 on days with at least one abnormal bowel movement.7 This stool chart plays a key role in ibs c diagnosis.

The Prevalence and Impact of IBS: Unveiling the Iceberg

Globally, IBS ranks among the most commonly diagnosed gastrointestinal disorders, although prevalence rates exhibit considerable variation across different geographical regions. A meta-analysis encompassing 80 distinct study populations and 260,960 participants estimated the global prevalence of IBS to be 11.2% (95% CI 9.8%–12.8%), with regional prevalence rates ranging from 2.6% to 32%.9 When considering IBS subtypes, IBS-C emerges as the most prevalent, accounting for more than one-third (35%) of all IBS cases.9 A comprehensive meta-analysis of 56 studies involving 188,229 subjects revealed that the prevalence of IBS in women was 67% higher compared to men (95% CI 1.53–1.82).10 This increased prevalence in women was predominantly observed in Western countries. Women with IBS were also more likely to experience constipation-predominant IBS (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.45–3.92) compared to the diarrhea-predominant subtype.10

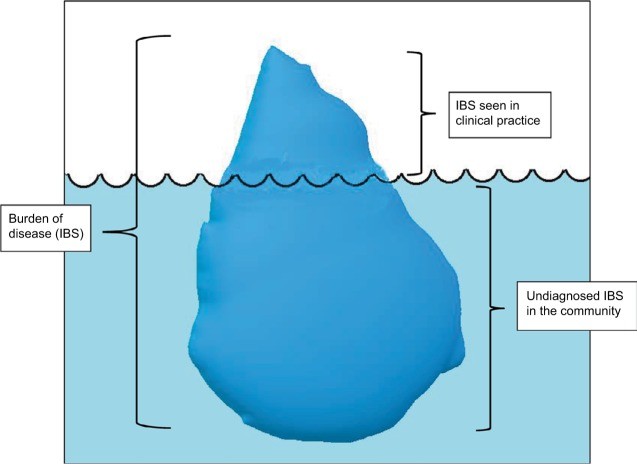

IBS commonly manifests between the ages of 11 and 40. It’s estimated that 10% to 70% of individuals experiencing IBS symptoms seek consultation from a primary care physician, although these figures vary significantly across different countries.12 In the United States, approximately 30% of individuals with IBS symptoms consult a primary care physician.12 Given that a substantial proportion of individuals with IBS symptoms do not seek medical attention, the precise prevalence of IBS remains uncertain. It is widely believed that the proportion of individuals with IBS symptoms seen in clinical practice represents only the visible “tip of the iceberg,” with a larger, submerged portion representing undiagnosed cases in the community (Figure 1). This highlights the importance of improving ibs c diagnosis in primary care.

Figure 1.

Burden of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Note: The submerged portion of the iceberg represents undiagnosed IBS in the community, while the tip (not submerged) represents IBS seen in clinical practice, emphasizing the challenge in ibs c diagnosis and broader IBS recognition.

The Significant Burden of Irritable Bowel Syndrome

The impact of IBS, both on individuals and healthcare systems, is substantial. IBS is associated with significant morbidity and loss of disability-adjusted life-years. Patients with mild to moderate IBS experience an average of 73 missed workdays annually.11 Another study indicated that an IBS-C diagnosis is linked to approximately 4.9 disrupted-productivity days per month on average.13 The personal financial burden of IBS is estimated to range from US$1,562 to $7,547 per year.14 In the US, the cost of IBS treatment is estimated to be between $1.7 billion and $10 billion in direct medical expenses and $20 billion in indirect costs annually.15 Annual healthcare costs for IBS-C patients have been found to be significantly higher compared to those without IBS ($8,621 vs $4,765).16 These figures underscore the importance of effective ibs c diagnosis and management to mitigate both personal and societal costs.

Diagnosing Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Primary Care Settings

Primary care settings differ from specialized care due to the established relationship between primary care physicians and their patients. This familiarity fosters a patient-physician rapport, which is advantageous in managing IBS, allowing for a holistic view of the condition rather than isolated symptoms. This is particularly relevant in the context of chronic conditions like IBS,12 where continuity of care is essential.

IBS presents a unique challenge for primary care physicians due to its diagnostic complexity and symptom overlap with other functional gastrointestinal disorders.12 In primary care, the ibs c diagnosis process is typically empirical, often relying on exclusion of other conditions.17,18 While thorough and pragmatic, this approach can be resource-intensive, time-consuming, and potentially unaffordable in resource-limited environments. Diagnostic criteria like the Rome criteria and guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend a positive ibs c diagnosis based on the symptom profile. However, these formal criteria have been criticized for being overly restrictive and less practical for ibs c diagnosis in primary care.19 Studies indicate that primary care physicians often lack familiarity with formal diagnostic criteria.17 Nevertheless, research has demonstrated that formal criteria can be valuable tools for ibs c diagnosis in primary care. For example, one study showed that applying Rome III criteria successfully identified 75% of patients already diagnosed with IBS in primary care, supporting their applicability in these settings.20 The latest Rome IV revision incorporates biopsychosocial factors, multicultural considerations, gender-specific aspects, and the role of the brain-gut axis, potentially making it more relevant to primary care, although validation studies are still needed.1

Both the Rome Foundation and NICE guidelines advocate for a positive ibs c diagnosis based on four core principles: a comprehensive and effective clinical history, physical examination, selective and pertinent laboratory investigations, and, when clinically indicated, further relevant investigations and procedures such as colonoscopies to exclude organic causes of abdominal pain.

The Pivotal Role of Clinical History in IBS-C Diagnosis

A detailed clinical history is the cornerstone of ibs c diagnosis. History taking should concentrate on the following key elements:7

- Abdominal Pain: This is a prerequisite for ibs c diagnosis; the absence of abdominal pain effectively rules out IBS. Pain is usually described as vague and diffuse, but can sometimes be localized to the lower abdomen and may be relieved by defecation. However, it’s important to note that pain can occasionally worsen after bowel movements.7

- Disordered Defecation: A history of altered bowel habits related to abdominal pain is almost universally present in IBS patients. The Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) is a crucial tool for documenting stool consistency. An increasing number of consecutive days without bowel movements suggests IBS-C. 7 Specifically, IBS-C is characterized by more than 25% of bowel movements being BSFS types 1 and 2, and less than 25% being BSFS types 6 and 7.7 Alternatively, IBS-C can be diagnosed when a patient reports a predominance of constipation, with stools resembling types 1 and 2 on the BSFS.7 It’s recommended that patients with IBS symptoms maintain a 2-3 week bowel diary using the BSFS prior to their clinical consultation to assist primary care physicians in making a positive ibs c diagnosis. To classify a patient as IBS-C, they should not be taking medications to manage bowel habit abnormalities.7

- Bloating: This symptom is common in IBS patients, but is neither specific nor required for ibs c diagnosis.

- Abdominal Distension: Similar to bloating, abdominal distension is frequently reported by IBS patients but is not a diagnostic criterion for ibs c diagnosis.

Psychosocial History: An Integral Component

Primary care physicians must recognize the significant role of psychological factors and enhance their assessment of psychosocial comorbidities in IBS. It’s recommended to approach psychosocial assessment as a screening process to identify patients at risk of refractory IBS, those who may respond poorly to treatment, and those with reduced quality of life.21 Eliciting a psychosocial history requires sensitivity, particularly when inquiring about potentially sensitive topics such as a history of abuse, depression, suicidal thoughts, and the nature of personal relationships.21

Patients should be questioned about their perceived social support systems. Research has shown that individuals experiencing stressful life events are more prone to IBS symptom exacerbations and tend to seek healthcare more frequently.21 Primary care providers should also be aware of the independent associations between anxiety and depression and IBS. Anxiety is present in 30%-50% of IBS patients.21 Patients with IBS frequently experience extraintestinal symptoms like headaches, fibromyalgia, and chronic pelvic pain, likely representing somatization of their IBS symptoms.21 Table 1 lists common comorbidities associated with IBS, which can influence ibs c diagnosis and management.

Table 1.

Frequent comorbidities in IBS seen in primary care

| Comorbidity | Comments |

|---|---|

| Fibromyalgia | Most well-recognized and frequently encountered comorbidity in IBS patients;53,54 can be present in up to 33% of IBS patients.55 |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | Presence of chronic fatigue syndrome in IBS has been found to be about 14%.55 |

| Chronic pelvic pain | Significant association with IBS reported in a large study;54 nearly 35% of women with IBS found to experience chronic pelvic pain.55 |

| Temporomandibular joint disorder | A small study found that 16% of IBS patients had temporomandibular joint disorder.54 |

| Major depression | Most frequent psychiatric comorbidity associated with IBS.55,56 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | Second-commonest psychiatric comorbidity seen in IBS patients.55,57 |

Abbreviation: IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

Questionnaires can enhance clinical assessment. It’s important to use validated, reliable questionnaires that are relatively free from bias. Tools like the Trauma History Questionnaire, Perceived Stress Questionnaire, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, depression and anxiety disorder modules of the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7), Short Form (SF)-36, or the shorter SF-12 and SF-8 are examples of helpful questionnaires for obtaining a psychosocial history relevant to ibs c diagnosis and management.21

Dietary History: Uncovering Triggers

A detailed dietary history is crucial in aiding ibs c diagnosis. Certain foods can exacerbate IBS symptoms. Diets high in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) can worsen IBS symptoms, particularly bloating and excessive gas.22 Patients should be encouraged to keep a food diary to assess the relationship between their IBS symptoms and food intake, providing valuable information during clinical encounters and aiding in ibs c diagnosis.

Menstrual, Gynecologic, and Sexual History: Considering Gender-Specific Factors

A complete clinical history must include a gynecologic, sexual, and menstrual history. Gender differences in IBS, though sometimes subtle, should be recognized and investigated. Abdominal pain can be linked to the menstrual cycle, causing cyclical pain threshold changes.23 Women often report more frequent and severe IBS symptoms during menstruation, with worsening abdominal pain likely related to menstrual cycle fluctuations.24 Menopause also appears to be associated with exacerbation of IBS complaints.25 Women with dysmenorrhea are twice as likely to experience increased IBS symptoms compared to those without dysmenorrhea.25 Gynecologic issues are more commonly reported in women with IBS; hysterectomy rates are reported to be three times higher in women with IBS.24 Therefore, in women presenting with IBS symptoms, special attention should be paid to menstrual irregularities, menopausal status, contraceptive and hormone replacement therapy use, and history of gynecologic surgery. These factors are important to consider for accurate ibs c diagnosis in women.

Diagnostic Testing for IBS-C in Primary Care: Targeted Investigations

A positive ibs c diagnosis should be made after limited, but relevant investigations. When diagnostic tests are necessary, they should be guided by patient age, symptom duration and severity, psychosocial factors, presence of alarm symptoms, and family history of colon cancer. A complete blood count (CBC) is typically the initial investigation ordered by primary care physicians. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), or fecal calprotectin may be necessary to rule out inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), although IBD typically presents with diarrhea rather than constipation. Similarly, gluten sensitivity is more prevalent in diarrhea-predominant IBS, and testing for tissue transglutaminase antibodies (tTG-IgA) may be considered, although routine antibody testing is not clearly recommended.26 Thyroid function tests may be obtained if thyroid abnormalities are suspected.7,27 Testing for hypo/hypercalcemia may be warranted if thyroid and/or parathyroid abnormalities are suspected. Recent research suggests a significant prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in IBS sufferers, but current evidence does not support routine screening or treatment of vitamin D deficiency in the context of ibs c diagnosis or management.28

Tests such as ultrasound, rigid/flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy, barium enema, thyroid function tests (unless clinically indicated), stool ova and parasites, fecal occult blood (unless alarm symptoms present), and hydrogen breath tests (for lactose intolerance and bacterial overgrowth, unless clinically indicated) are generally not necessary for patients meeting IBS criteria, especially for ibs c diagnosis in the absence of red flags.27 Screening colonoscopy is indicated for patients aged >50 years without warning signs or when alarm symptoms are present.7

Physical Examination: Ruling Out Organic Causes

The physical examination in patients with IBS is often unremarkable. However, while of limited diagnostic utility for ibs c diagnosis itself, a physical examination is valuable in excluding organic causes of IBS and systemic diseases, while also providing reassurance to the patient. Particular attention should be paid to abdominal examination to identify any abdominal masses or organomegaly. An anorectal examination is an essential component of the abdominal examination, aiding in identifying anorectal causes of bleeding and dyssynergic defecation, and assessing anorectal tone and squeeze pressure.29 Anorectal manometry is more relevant for diarrhea-predominant IBS than constipation-predominant IBS.30 In women, a bimanual pelvic examination may be indicated.

Primary care physicians must be vigilant in recognizing alarm symptoms, or “red flags,” which necessitate further investigation and referral to secondary care. These include unintentional or unexplained weight loss, anemia, occult blood in stool, abdominal or rectal masses, new-onset IBS symptoms after age 50, family history of colon or ovarian cancer, positive markers for IBD, celiac disease, arthritis or skin findings on physical examination, signs and symptoms of malabsorption, and signs and symptoms of thyroid dysfunction.27,31 The presence of alarm symptoms should prompt a re-evaluation of the ibs c diagnosis and consideration of alternative diagnoses.

Treatment of IBS-C in Primary Care: A Multimodal Approach

Treatment of IBS-C should emphasize empathy, reassurance, dietary and lifestyle adjustments, brief counseling, and judicious use of evidence-based pharmacologic therapy.21 Management of mild IBS-C should focus on patient education, reassurance, and dietary modifications.32 Moderate to severe IBS-C often requires pharmacotherapy and behavioral interventions such as cognitive behavior therapy and mindfulness-based therapy.32,33

A multidisciplinary approach to IBS treatment is increasingly becoming standard practice. This integrated approach involves a team comprising a primary care physician, a psychologist or psychiatrist, a dietician, and a nurse practitioner.34 The roles of the primary care physician and psychologist are especially critical, given the persistent nature of IBS symptoms and the numerous psychological comorbidities associated with the condition, both impacting ibs c diagnosis and long-term management.

Dietary and Lifestyle Recommendations

The importance of self-management should be emphasized to individuals with IBS-C. Patient education should be tailored to individual needs.21 Patients should be encouraged to learn relaxation techniques and advised to increase physical activity levels if inadequate. Adopting healthy eating habits, such as regular meals and avoiding long intervals between meals, should be stressed.27 Adequate water intake should also be encouraged. Fiber intake should be reviewed at each visit, and if increased dietary fiber is recommended, soluble fiber sources such as psyllium powder or foods rich in soluble fiber like oats are preferred.27 Limiting dietary FODMAPs may offer some symptom relief in IBS-C, particularly for bloating.35 Gluten reduction may be beneficial, but excluding gluten from the diet when already following a low-FODMAP diet may not provide additional benefit.7 These dietary and lifestyle modifications are crucial components of ibs c diagnosis management.

Various other treatments, including pharmacological and behavioral interventions, are available for IBS-C patients, with varying levels of evidence. Table 2 lists prominent therapies for IBS-C. The following section focuses on linaclotide, a novel drug with pro-secretory and anti-nociceptive properties, demonstrating high efficacy in reducing IBS-C symptoms.

Table 2.

Commonly used therapies for IBS-C

| Treatment modality | Evidence quality | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Fiber: psyllium | Moderate | May cause bloating and flatulence; may increase abdominal pain. |

| Laxative: polyethylene glycol (macrogol) | Very low | Bloating, cramping, and diarrhea if taken in excess; may not be better than placebo in reducing abdominal pain;58 limited evidence from RCTs. |

| Antidepressants: TCAs and SSRIs | High | SSRIs generally have a favorable side-effect profile when compared to TCAs (dry mouth, sedation, constipation, flushing). |

| Prosecretory agent: lubiprostone | Moderate | Nausea is the predominant side effect. In the US, only 8 μg dose is approved by the FDA for women only.48 |

| Prosecretory agent: linaclotide | High | Diarrhea is the most common adverse event. |

| Psychological therapy: CBT, mindfulness therapy, and hypnotherapy | Very low | CBT is the most widely studied psychotherapy for IBS, and may be first-line behavioral intervention for IBS-C.33 No behavioral modification is likely better than placebo. |

Note: Data from Chey et al.59

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; SSRIs, selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants.

Pharmacotherapy for IBS-C: The Role of Linaclotide

Studies show that over 80% of IBS patients receive some form of treatment during their initial consultation, with the majority (74%) being prescribed medication for their GI symptoms.36 IBS patients often report using multiple medications, yet only a third report significant improvement or satisfaction with their current therapy.37 This highlights the need for effective medications that are easily prescribed in primary care, supported by strong evidence, and relatively free of major side effects. Linaclotide, a first-in-class synthetic guanylate cyclase C (GCC) agonist, has demonstrated effectiveness in improving IBS-C symptoms and is strongly recommended by the American Gastroenterological Association for IBS-C treatment.38 While not directly related to ibs c diagnosis, effective treatment is a crucial aspect of patient care following diagnosis.

Linaclotide (Linzess; Allergan) activates intestinal GCC receptors, increasing both intracellular and extracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels by mimicking endogenous intestinal peptides, guanylin, and uroguanylin.39,40 GCC activation stimulates chloride and bicarbonate secretion via CFTR activation and inhibits Na+ absorption by blocking an apical Na+-H+ exchanger.40 It accelerates colonic transit in IBS-C in a dose-dependent manner.41 Linaclotide’s pain-modulating effects are likely due to increased extracellular cGMP, which inhibits visceral nociception.42 It is acid-stable, pepsin-stable, and minimally absorbed. In human colonic mucosa, linaclotide binds GCC receptors with high affinity across a range of pH levels.39

Evidence for linaclotide use in IBS-C comes from three randomized controlled trials.43–45 All trials used Rome III criteria for patient recruitment and included predominantly women (>90%). Linaclotide reduced constipation and abdominal pain symptoms in IBS-C patients in Phase IIB and Phase III trials. It is approved for IBS-C treatment (290 μg once daily) by global regulatory bodies like the US FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Compared to placebo, more patients on linaclotide achieved significant endpoints, such as adequate relief and global relief responses.46 Linaclotide also outperformed placebo in meeting stricter outcome endpoints set by the FDA and EMA for IBS-C drug evaluation.46 The FDA endpoint demonstrates reasonable sensitivity (60.7%) and high specificity (93.5%) in detecting clinically meaningful improvement in IBS-C symptoms.47

Diarrhea is the most common side effect of linaclotide reported in pooled placebo-controlled IBS-C trials. In these trials, 20% of linaclotide-treated patients reported diarrhea versus 3% on placebo.48 Severe adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation were also significantly higher in the linaclotide group (RR 14.75, 95% CI 4–53.8). In open-label, long-term trials, 2,147 IBS-C patients received 290 μg linaclotide daily for up to 18 months. In these trials, 29% had dose reduction or suspension due to adverse reactions, primarily diarrhea.48

An expert consensus report on optimizing linaclotide use for IBS-C offers the following recommendations: linaclotide is indicated for moderate-severe IBS-C in adults; continuous, not sporadic, use is recommended; patients should be informed about diarrhea risk and management options; and the absence of tachyphylaxis or long-term risks suggests linaclotide can be continued long-term.49

Limitations of linaclotide in primary care include potential diarrhea side effects leading to discontinuation, rare but serious dehydration requiring secondary or tertiary care, limited cost-effectiveness data,50,[51](#b51-ijgm-10-385] and contraindication in pediatric patients (aged 6–18 years) due to unestablished safety in this population.48 These factors should be considered post ibs c diagnosis when discussing treatment options.

Conclusion: Optimizing IBS-C Diagnosis and Care in Primary Settings

Accurate ibs c diagnosis requires a personalized approach, targeted investigations, and consistent follow-up. While primary care physicians often correctly suspect IBS, they may still rely on unnecessary and costly investigations. 17 However, their role in reducing the community burden of IBS is paramount.17

Primary care settings are often resource-constrained, emphasizing the need for positive ibs c diagnosis based on formal criteria, thorough clinical history, and limited, relevant investigations. Validating patient complaints, clear explanations of IBS, empathy, and strong patient rapport are crucial for effective IBS management.11 Primary care physicians must also recognize cross-cultural nuances in symptom presentation and management, given the diverse patient populations they serve.52

Linaclotide is a valuable addition to the IBS drug repertoire available to primary care physicians. Clinical trials provide strong evidence of its effectiveness in improving IBS-C symptoms and patient quality of life. However, its potential for diarrhea as a side effect, which can lead to treatment discontinuation, should be carefully considered. Treatment compliance is a critical aspect of primary care, and linaclotide may not be suitable for all IBS-C patients. Cost considerations should also be factored into prescribing decisions. The American Gastroenterological Association strongly recommends linaclotide for IBS-C, while acknowledging that patients prioritizing diarrhea avoidance and minimizing out-of-pocket expenses may prefer alternative treatments.38 Therefore, while ibs c diagnosis is the first step, comprehensive management requires careful consideration of treatment options and patient preferences.

While IBS prevalence decreases with age, constipation prevalence increases. However, data on IBS-C drug effectiveness, like linaclotide, in elderly patients are limited. Older patients may exhibit different safety profiles. IBS-C drug trials often over-represent younger white women, limiting generalizability to broader patient populations. Recruitment from tertiary clinics, where women are more likely referred, may also introduce selection bias. Future trials with larger, gender-balanced samples and heterogeneous age groups are needed to better understand the effectiveness of newer IBS-C drugs across diverse populations and improve post-ibs c diagnosis care.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.