Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a widespread gastrointestinal disorder affecting a significant portion of the global population. Among the IBS subtypes, diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) is particularly common. Accurate Ibs D Diagnosis is crucial for effective management and patient care. This article provides a detailed overview of IBS-D, focusing on its diagnosis, underlying mechanisms, and current treatment strategies, aiming to enhance understanding and optimize diagnostic approaches for healthcare professionals.

Understanding IBS-D: Pathophysiology

To effectively approach ibs d diagnosis, it’s important to understand the complex factors contributing to its development. IBS-D is not simply a digestive issue; it involves intricate interactions between diet, gut function, the nervous system, and gut microbiota.

Dietary Factors

Diet plays a significant, though not fully understood, role in IBS. The digestive process itself is a complex interplay of neural, hormonal, and immunological signals between the gut and brain. Dietary components can disrupt this delicate balance. Changes in gut microbiota, gut permeability, and inflammatory responses, whether from food sensitivities or alterations in microbial composition, can contribute to visceral hypersensitivity and communication breakdowns in the brain-gut axis, key features of IBS.

Accelerated Transit

The enteric nervous system (ENS), often referred to as the “brain of the gut,” uses neurotransmitters like serotonin to regulate various gastrointestinal functions. These include motility, secretion, absorption, mucosal health, blood flow, and immune responses. Serotonin receptors are abundant in the ENS and are vital in controlling reflexes related to gut motility, secretion, and visceral sensation. In IBS-D patients, disruptions in serotonin signaling have been observed, such as an increased number of serotonin-producing cells, altered serotonin release, and changes in serotonin reuptake. These disruptions can lead to accelerated transit, contributing to diarrhea.

Visceral Hypersensitivity

Visceral hypersensitivity, an increased sensitivity to sensations within the gut, is a hallmark of IBS. While not all IBS patients experience altered visceral perception, many, particularly those with IBS-D, have lowered thresholds for bloating and other gut sensations. This hypersensitivity involves sensitization of neurons that transmit sensory information from the ENS to the central nervous system (CNS). Factors like inflammatory mediators, potentially triggered by changes in gut microbiota or prior gastroenteritis, can contribute to this heightened sensitivity and abdominal pain. Furthermore, studies have indicated alterations in CNS processing of gastrointestinal signals in IBS patients, suggesting a more complex interplay beyond just peripheral nerve sensitization. In IBS-D, increased mast cells in the colon, their proximity to nerves, and augmented brain responses to pain and motor stimuli further underscore this enhanced reactivity of the GI tract.

Gut Microbiota

The gut microbiota, the vast community of microorganisms residing in our intestines, is crucial for structural, metabolic, and immune functions. In healthy individuals, this ecosystem is relatively stable. However, in IBS-D, disruptions in the gut microbiota, known as dysbiosis, are frequently observed. Dysbiosis can affect brain-gut communication, neuroendocrine regulation, and immune homeostasis, potentially contributing to IBS-D symptoms. Post-infectious IBS, developing after gastroenteritis, highlights the microbiota’s role. Studies comparing the gut microbiota of IBS-D patients to healthy individuals and other IBS subtypes have revealed significant differences in composition and diversity. While the full implications of dysbiosis in IBS-D are still under investigation, the effectiveness of treatments targeting the microbiota, such as probiotics and non-systemic antibiotics, suggests a crucial role in symptom management.

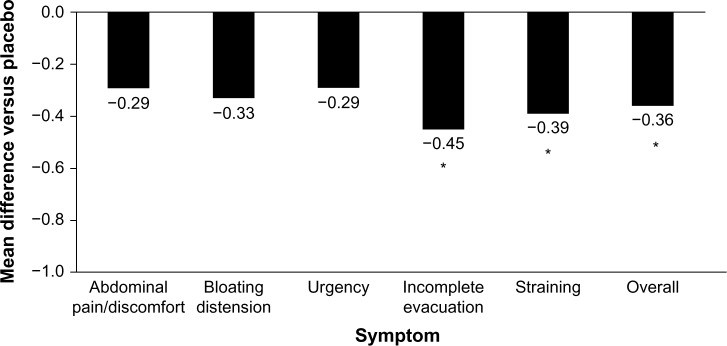

Image alt text: Bifidobacterium infantis Probiotic Effect on IBS-D Symptoms Reduction. Graph showing statistically significant improvement in incomplete evacuation, straining, bowel habit satisfaction, and overall IBS symptoms with Bifidobacterium infantis compared to placebo in IBS-D patients.

IBS-D Diagnosis: A Symptom-Based Approach

The ibs d diagnosis process typically starts with recognizing the characteristic symptoms. Patients commonly report abdominal pain associated with frequent loose stools, cramping, urgency, and mucus in stools. The presence of other functional GI disorders like GERD or dyspepsia, and extraintestinal conditions such as migraines or fibromyalgia, can strengthen the suspicion of IBS. Symptom severity varies, but even mild to moderate symptoms often require ongoing management.

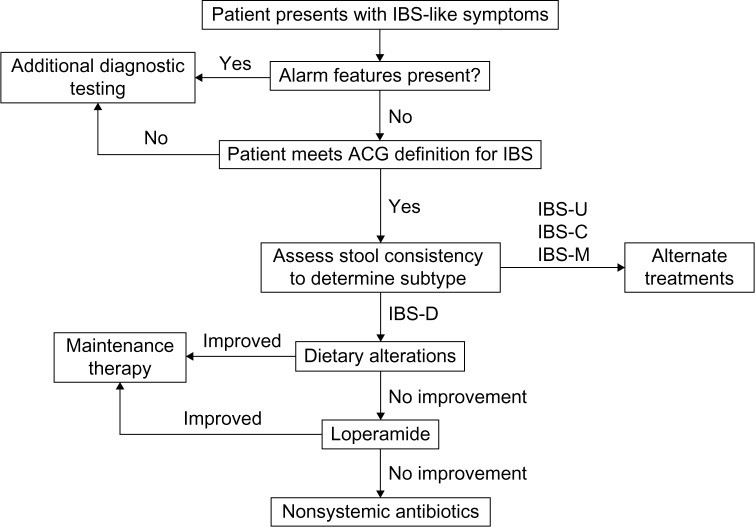

Primary care physicians (PCPs), particularly internists and family practitioners, are often the first point of contact for ibs d diagnosis. Importantly, diagnosis can usually be achieved through a detailed patient history and physical examination, without the need for extensive, specialized testing. The diagnostic strategy is primarily symptom-based, relying on:

- Patient History: A thorough account of the patient’s symptoms, including onset, duration, frequency, and factors that worsen or relieve them.

- Exclusion of Alarm Symptoms: Identifying and ruling out “red flag” symptoms that suggest other organic diseases (see Table 2).

- Rome III or Rome IV Criteria: Utilizing standardized criteria like Rome III or the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) definition of IBS, which emphasizes recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort associated with altered bowel habits for at least 3 months.

While testing for celiac disease might be considered in diarrhea-predominant cases, extensive diagnostic testing is generally discouraged in the absence of alarm symptoms. Studies indicate that PCPs and non-specialists tend to perform more tests before confirming an ibs d diagnosis. However, many of these tests, such as complete blood counts, CRP, serum chemistries, stool parasite tests, and sigmoidoscopy in the absence of alarm features, have limited diagnostic value in typical IBS cases. Focusing on addressing patient concerns, setting realistic treatment goals, patient education, and managing any underlying psychological factors may be more beneficial than extensive testing in most cases of suspected IBS-D.

Differential Diagnosis and Alarm Symptoms

It’s critical to differentiate IBS-D from other conditions. Certain “alarm symptoms” warrant further investigation to rule out organic diseases.

Table 2. Differential Diagnosis and Alarm Symptoms in IBS

| Alarm symptoms/warning signs | Potential differential diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Anemia | Celiac disease, colon cancer |

| Family history of colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, or celiac disease | Celiac disease, IBD, colon cancer |

| Nocturnal diarrhea that awakens the patient | Colorectal cancer, IBD, microscopic colitis |

| Onset >50 years of age | Microscopic colitis, colon cancer |

| Recent antibiotic use | Clostridium difficile colitis |

| Rectal bleeding | IBD, colon cancer, hemorrhoids, ischemic colitis |

| Unintentional weight loss (>10% of body weight) | Ischemic colitis, IBD, celiac disease, colon cancer |

| Persistent frequent diarrhea without hematochezia | Bile acid malabsorption |

| Persistent bloating and diarrhea unresponsive to dietary interventions | Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth |

Table summarizing alarm symptoms and potential differential diagnoses for IBS, including conditions like celiac disease, colon cancer, IBD, and microscopic colitis.

Image alt text: IBS-D Diagnostic and Treatment Algorithm Flowchart. Diagram outlining the step-by-step process for diagnosing and treating IBS-D, starting with symptom evaluation and progressing through treatment options based on subtype and symptom severity.

Treatment Options for IBS-D

Once an ibs d diagnosis is established, a range of treatment options can be considered. These include both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic approaches, tailored to individual patient needs and symptom profiles.

Pharmacologic Treatments

Several medications are used to manage IBS-D symptoms, targeting different aspects of the condition’s pathophysiology.

Antimotility Agents: Loperamide and Eluxadoline

- Loperamide: This over-the-counter opioid agonist reduces bowel movements by slowing peristalsis and increasing intestinal transit time. It effectively reduces stool frequency, improves stool consistency, and decreases urgency. However, it does not typically relieve bloating or abdominal pain, key IBS symptoms. While generally well-tolerated, loperamide is not strongly recommended by guidelines due to limited high-quality evidence of overall benefit in IBS-D.

Image alt text: Loperamide Symptom Improvement in IBS-D Patients. Graph depicting the statistically significant symptom improvement observed with loperamide treatment in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS, particularly in stool frequency and consistency.

- Eluxadoline: A newer medication, approved in 2015, eluxadoline is a mixed opioid receptor agonist and antagonist. It reduces GI contractility and secretion. Clinical trials have demonstrated significant improvements in abdominal pain and stool consistency in IBS-D patients. Eluxadoline has shown benefit even in patients who haven’t found relief with loperamide. Common side effects include constipation and nausea.

Serotonergic Agents: Alosetron

- Alosetron: This serotonin receptor antagonist is available under a risk management program for severe IBS-D in women. Clinical trials have shown alosetron improves stool consistency, frequency, and overall IBS symptoms in women. However, its efficacy in men has been less consistent. Alosetron carries a risk of constipation and, more seriously, ischemic colitis, which led to its temporary market withdrawal in the past. Its use is now restricted to women with severe IBS-D who meet specific criteria and are enrolled in a risk management program.

Antidepressants: Tricyclic Antidepressants and SSRIs

- Antidepressants: Both tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can modulate serotonin activity in the GI tract and reduce global IBS symptoms and abdominal pain. TCAs, which slow intestinal transit, may be preferred for IBS-D. However, evidence specifically for IBS-D is limited. Amitriptyline, a TCA, has shown some benefit in reducing incomplete defecation and loose stools in IBS-D patients. Side effects like drowsiness and dry mouth are common and can limit tolerability. Current guidelines do not strongly recommend antidepressants for IBS-D due to side effects, cost (especially SSRIs), and potential patient reluctance.

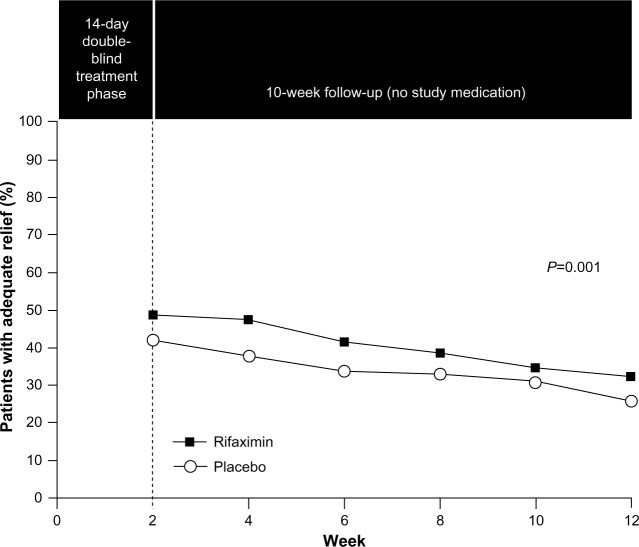

Non-Systemic Antibiotics: Rifaximin

- Rifaximin: This non-systemic antibiotic was approved in 2015 for IBS-D treatment. It targets gut microbiota modulation. Clinical trials demonstrated that rifaximin significantly increased the percentage of patients achieving adequate relief of global IBS symptoms and improved bloating for up to 10 weeks post-treatment. Retreatment studies have also shown benefit in symptom recurrence. Rifaximin’s side effect profile is generally similar to placebo, with nausea, diarrhea, and sinusitis being slightly more common. While generally safe, there is a potential risk of C. difficile infection, as with most antibiotics. Rifaximin is considered a viable option for IBS-D, but response rates are not universal.

Image alt text: Rifaximin Efficacy in IBS-D Treatment. Graph illustrating the significant efficacy of rifaximin compared to placebo in providing adequate relief of IBS symptoms in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS over a 12-week study period.

Non-Pharmacologic Treatments

Beyond medications, lifestyle and dietary modifications play an important role in IBS-D management.

Probiotics

While intuitively appealing for IBS-D given the gut microbiota’s role, clinical evidence for probiotics is mixed and strain-dependent. Quality and consistency of probiotic products can also be variable. Some studies, like those using VSL#3, have shown no benefit in IBS-D symptoms. However, other studies, such as with Bifidobacterium infantis, have demonstrated improvements in specific symptoms like incomplete evacuation, straining, and overall IBS symptoms. While B. infantis may offer symptom relief for some, the evidence base is limited, and cost-benefit should be considered.

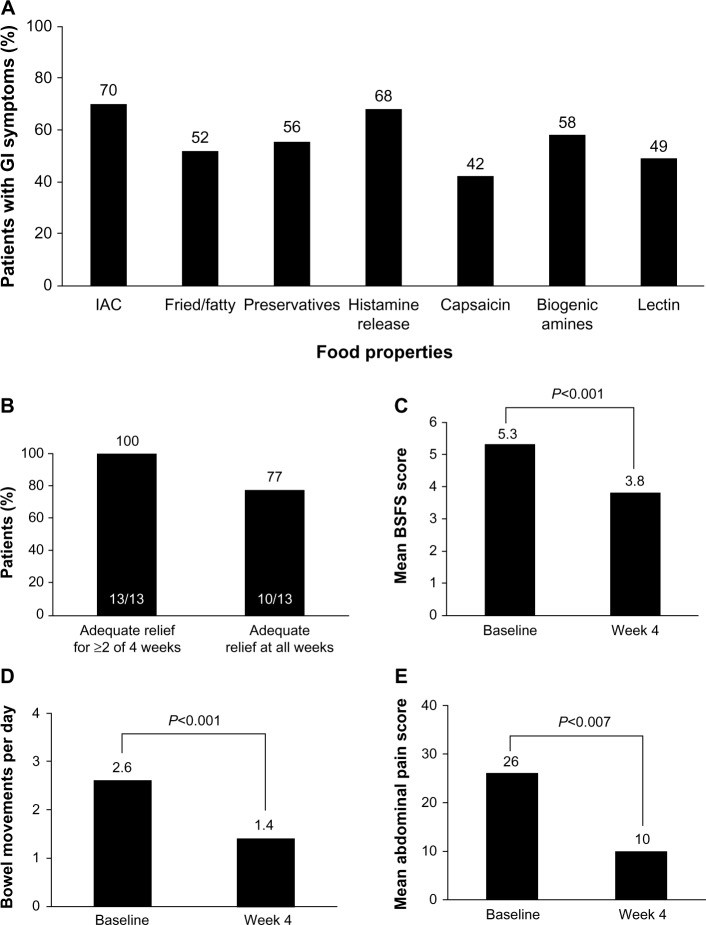

Dietary Modification

Many IBS patients link symptom onset to specific foods, particularly fatty or fried foods. While rigorous trials are lacking, some dietary modifications show promise. A low-FODMAP diet (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) may reduce symptoms, especially in IBS-D. Gluten-free or very low-carbohydrate diets have also shown benefits in small trials, improving stool frequency, consistency, and abdominal pain in IBS-D. However, due to limited strong evidence and high patient adherence demands, dietary modifications are not strongly recommended by guidelines, but can be considered under medical supervision.

Image alt text: Dietary Triggers and Low-Carb Diet Efficacy in IBS-D. Composite figure showing common food triggers for GI symptoms in IBS patients and graphs demonstrating the efficacy of a very low-carbohydrate diet in improving stool consistency, frequency, and abdominal pain in IBS-D.

Fecal Microbiota Transplant (FMT)

FMT, involving the transfer of stool from a healthy donor to the patient, is being investigated for restoring gut microbiota in IBS. While showing promise in other GI conditions like C. difficile infection, data for IBS-D are very limited. FMT for IBS-D should be considered investigational due to unknown efficacy and safety concerns, including transient GI symptoms and potential autoimmune risks.

Conclusion: Optimizing IBS-D Diagnosis and Management

IBS-D diagnosis and management are critical for improving the quality of life for affected individuals and reducing the societal burden of this common condition. While the exact causes of IBS-D are still being researched, it’s clear that a combination of visceral hypersensitivity, altered GI motility, and gut microbiota dysbiosis plays a significant role. PCPs are central to the ibs d diagnosis process and initial management. A symptom-based approach, focusing on excluding alarm signs, identifying the IBS subtype, and tailoring treatment based on risk-benefit assessment, is recommended. Extensive diagnostic testing without alarm symptoms should be avoided to minimize unnecessary healthcare costs. Several treatment options are available, including newer medications like eluxadoline and rifaximin, offering effective alternatives for managing IBS-D symptoms. Continued research and personalized approaches are essential to optimize ibs d diagnosis and treatment strategies, ultimately improving patient outcomes in this prevalent and challenging condition.

References