Patients today actively seek knowledge about their health conditions, underscoring the critical need for healthcare providers (HCPs) to deliver comprehensive yet easily digestible education. Providing patients with updated, thorough, and concise educational resources, coupled with consistent educational methodologies from HCPs, is paramount for enhancing patient care.

Prior to this study, a detailed review of existing literature on patient education materials was conducted to establish a strong foundation. This review included comparisons across various resources to determine best practices in patient education. The focus was placed on empowering HCPs to effectively utilize patient education tools, particularly those integrated within electronic health record (EHR) systems, including digital platforms like patient portals, to optimize patient education.

Strategies were developed to streamline the process of accessing and delivering relevant patient education materials, aiming for a more efficient and impactful approach. Personalized patient education handouts, complementing verbal instruction from HCPs, are crucial for improving a patient’s overall well-being – both physically and psychologically. This approach fosters shared decision-making, boosts patient satisfaction, and strengthens health literacy, ultimately leading to enhanced patient care.

Keywords: electronic health record, quality improvement, plan-do-study-act cycle, health literacy, patient education

Introduction

In today’s healthcare landscape, patients are not passive recipients of care; they are proactive individuals eager to understand their health status and medical conditions. Equipping them with pertinent, current, consistent, and updated information is not just good practice—it is essential for empowering patients and their families to actively participate in medical care and decision-making processes [1]. This proactive engagement leads to better health outcomes and a more patient-centered approach.

Formal patient education is a cornerstone of effective healthcare. Patients require in-depth knowledge about their diagnosed condition, encompassing everything from understanding their symptoms to navigating diagnostics and adhering to medication regimens. Crucially, they must also be educated on when and how to seek timely medical assistance. While a plethora of patient education resources exist for various conditions, the challenge lies in discerning which resources are most appropriate for specific diseases or conditions and which provide information in a clear and concise manner. High-quality patient education materials serve to improve patient health literacy, empowering them to make informed decisions grounded in the most current medical evidence and aligned with their personal preferences [2].

Aims

This study aimed to develop and refine patient education handouts and materials that are both up-to-date and readily accessible. These resources were designed to complement verbal counseling from HCPs, ensuring patients receive comprehensive guidance on their conditions, diagnostic procedures, medication management, and critical steps for seeking help when needed. A key objective was to encourage the consistent use of standardized patient education materials among HCPs to ensure uniform and effective communication.

Objectives

The specific objectives of this study were multifaceted:

- To implement quality improvement methodologies, specifically Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles, to refine patient education practices within clinical settings.

- To enhance the delivery of patient education and foster greater awareness among HCPs regarding its significance in improving patient health literacy.

- To evaluate existing patient education handouts to confirm they include the minimum essential information patients need to know to manage their health effectively.

- To benchmark patient education handouts available within electronic health record (EHR) systems against leading patient education databases, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and MedlinePlus®, ensuring they meet established standards for necessary information.

- To educate and motivate HCPs to effectively utilize appropriate patient education articles directly within the EHR system and to leverage electronic patient portals as a tool for patient education. This aims to facilitate the transition to digital patient education resources, enhancing efficiency and ensuring consistent educational delivery.

Materials and Methods

A thorough investigation of patient education materials concerning prevalent medical conditions across diverse clinical settings was undertaken. We performed a comparative analysis of the patient education database integrated within our EHR system against recognized, reliable resources like the CDC and MedlinePlus. This retrospective chart review was crucial to guarantee that patients receive, at minimum, the necessary information for informed healthcare decisions.

To ensure the educational materials were robust and current, we broadened our comparison to include resources like UpToDate (covering both basic and advanced information), MedlinePlus, the US National Library of Medicine (NIH), the CDC, and the US Department of Health and Human Services. This comprehensive approach was designed to confirm that the educational content provided to patients was not only effective but also evidence-based and aligned with the latest medical knowledge.

To facilitate easy access within the EHR system, search terms were incorporated, allowing HCPs to efficiently locate educational articles by title. The educational materials selected for review focused on common medical conditions encountered in various clinical environments. The final patient handouts were structured to be versatile, suitable for electronic distribution via patient portals or for printing as needed.

To optimize the utilization of these resources, HCPs participated in educational sessions. These sessions incorporated qualitative and quantitative questionnaires administered both before and after the lecture to assess knowledge gain and practice changes. The effectiveness of these educational interventions was further evaluated through pre- and post-intervention surveys, gauging the impact of training on HCPs’ patient education practices.

Results

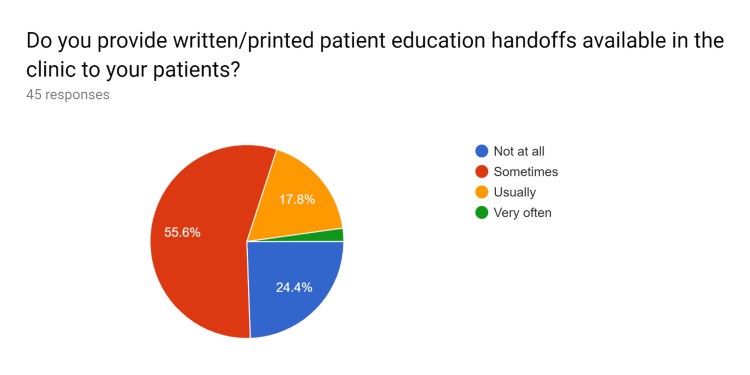

The study culminated in the creation of uniform, updated patient education handouts, rigorously vetted against standard, trusted resources. Initially, a pre-test survey was distributed to HCPs to gauge their existing knowledge, current practices in utilizing patient education handouts, and their familiarity with EHR systems in accessing standardized education materials. Following targeted education sessions for HCPs, a post-test survey was administered to assess improvements in their understanding and utilization of EHR-integrated patient education resources. Data analysis was conducted on the responses collected from both pre- and post-test surveys from HCPs. The results of these surveys are visually represented in Figures 1–20.

Figure 1. Pre-test survey responses: Initial assessment of HCP knowledge and practices before formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 2. Pre-test survey responses: Initial assessment of HCP knowledge and practices before formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 3. Pre-test survey responses: Initial assessment of HCP knowledge and practices before formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 4. Pre-test survey responses: Initial assessment of HCP knowledge and practices before formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 5. Pre-test survey responses: Initial assessment of HCP knowledge and practices before formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 6. Pre-test survey responses: Initial assessment of HCP knowledge and practices before formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 7. Pre-test survey responses: Initial assessment of HCP knowledge and practices before formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 8. Pre-test survey responses: Initial assessment of HCP knowledge and practices before formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 9. Pre-test survey responses: Initial assessment of HCP knowledge and practices before formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 10. Pre-test survey responses: Initial assessment of HCP knowledge and practices before formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 11. Post-test survey responses: HCP knowledge and practices after formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 12. Post-test survey responses: HCP knowledge and practices after formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 13. Post-test survey responses: HCP knowledge and practices after formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 14. Post-test survey responses: HCP knowledge and practices after formal training.

“Do you feel that attending and processing times required for fetching appropriate educational articles will be reduced if standard materials are outlined?”

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 15. Post-test survey responses: HCP knowledge and practices after formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 16. Post-test survey responses: HCP knowledge and practices after formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 17. Post-test survey responses: HCP knowledge and practices after formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 18. Post-test survey responses: HCP knowledge and practices after formal training.

“Do you think that efficient patient education is effective in creating and improving adherence to treatment, medication compliance, and for improving overall patient health?”

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 19. Post-test survey responses: HCP knowledge and practices after formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Figure 20. Post-test survey responses: HCP knowledge and practices after formal training.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Quality Improvement and Gap Analysis

Quality improvement (QI) is central to enhancing healthcare delivery. QI techniques, particularly PDSA cycles, were employed to optimize patient education across various clinical settings [1]. This structured approach allowed for iterative improvements based on data-driven insights.

Reasons for Action

The impetus for this QI initiative stemmed from the recognized need for updated and standardized patient education materials. Beyond verbal consultations, providing patients with tangible resources is vital to ensure they fully grasp their medical conditions, understand diagnostic procedures, manage medications correctly, and know when to seek further medical attention. This comprehensive education is crucial for bolstering patient health literacy. The abundance of existing patient education materials, while beneficial, necessitates a critical evaluation to determine the most suitable resources for specific conditions—materials that are not only informative but also concise and patient-friendly.

Initial State

Initially, our assessment focused on the patient education materials integrated within the EHR system. We compared these resources against current, authoritative sources, including MedlinePlus, the US National Library of Medicine of NIH, CDC, and the US Department of Health and Human Services. This comparative review was a foundational step before initiating any improvements.

Goal State

The desired outcome was to elevate the standard of patient education by drawing upon multiple reputable sources. A key focus was on practical aspects, such as medication usage instructions and clear guidelines on when to seek help. We aimed to evaluate the quality of educational materials across several critical domains: disease education, diagnostics, medication use, and guidance on seeking timely medical assistance. The aforementioned resources served as benchmarks for these quality assessments.

Gap Analysis

The results of the gap analysis, illustrating the discrepancies between the initial state and the desired goal state, are depicted in Figure 21.

Figure 21. Gap analysis: Identifying areas for improvement in patient education resources.

HCPs – healthcare providers

Solution Approach

Initially, patient education materials were primarily available in print, limiting accessibility and efficiency. To address this, we focused on leveraging the electronic patient portal to deliver educational materials in a digital format. This shift to electronic delivery promised to be faster, more efficient, and more environmentally sustainable.

The process of locating appropriate and up-to-date materials was often time-consuming for HCPs. This was due to the lack of a streamlined system for identifying relevant resources and the prevalence of outdated educational content. To mitigate this, we proposed creating a comprehensive index of educational articles for common medical conditions. Ensuring these articles were current and regularly updated was crucial to improving efficiency.

Recognizing the time constraints during patient appointments, we aimed to maximize the impact of each interaction. Detailed educational materials, delivered via the patient portal, could extend the educational process beyond the consultation itself. For patients with limited digital access, we ensured printed materials remained available, either provided during appointments or mailed to their homes if missed during the visit.

To overcome the limitations of relying solely on EHR databases, we broadened our approach to incorporate educational articles from diverse, reputable resources. Utilizing the newly developed index of educational articles for common conditions was also key to enhancing the quality and breadth of patient education.

Inefficiencies in using the EHR’s patient education capabilities, coupled with inadequate training for HCPs, were identified as key areas for improvement. Therefore, training programs were implemented to equip HCPs with the skills to efficiently use educational materials for their patients, thereby prioritizing and enhancing patient education practices.

Rapid Experiment: Plan-Do-Study-Act Cycle

To systematically improve patient education, we employed the PDSA cycle, a recognized framework for iterative testing and refinement in quality improvement.

Plan: The plan phase involved selecting appropriate patient education materials from a variety of sources, all organized within the newly created index of educational articles.

Do: During the ‘Do’ phase, HCPs were instructed to verbally counsel patients, supplement this with relevant educational materials, and then use a ‘verbal read-back’ technique. This technique involved asking patients to reiterate key information, such as how to take medications and when to seek help, ensuring initial comprehension.

Study: The ‘Study’ phase utilized the ‘teach-back’ method. Patients were asked to explain the information they received in their own words. This step was crucial to assess their understanding of their condition, diagnostics, medication regimen, and when to seek help, providing a clear measure of improved health literacy.

Act: In the ‘Act’ phase, any patient questions arising from the ‘teach-back’ were addressed immediately. If more in-depth discussion or follow-up was needed, a subsequent appointment was scheduled to ensure all educational needs were met.

Actions Taken

Several concrete actions were implemented based on the PDSA cycle and the identified needs:

- Creation of an Indexed Educational Material Database: An index of educational materials, specifically tailored to common medical conditions encountered in clinical settings, was developed. This index served as a practical guide for HCPs, enabling them to quickly and efficiently select relevant and appropriate articles for their patients across various clinical contexts.

- Promotion of EHR-Integrated Education Tools: Emphasis was placed on effectively utilizing patient education resources available within the EHR system. This included promoting the use of electronic methods, such as patient portals, to facilitate patient education and streamline the delivery of materials.

- Utilization of Diverse Educational Resources: HCPs were encouraged to broaden their resource pool beyond the EHR database, incorporating materials from other reputable sources to provide a richer and more comprehensive educational experience for patients.

- Availability of Printed Materials: To accommodate patients with limited access to technology, printed educational materials were made readily available. This ensured that all patients, regardless of their digital literacy, could benefit from tangible educational resources.

- Reduced Material Retrieval Time: By creating and utilizing the indexed database of educational articles focused on common medical situations, the time HCPs spent searching for appropriate materials was significantly reduced, enhancing efficiency in patient interactions.

- Efficient and Expedited Patient Education: These improvements collectively led to faster and more efficient patient education processes, reducing the administrative burden on HCPs and allowing for more focused patient interactions.

- Prioritization of Health Literacy Enhancement: The initiative underscored the importance of health education as a key component of patient care, directly aiming to improve overall health literacy within the patient population.

- Optimized EHR Utilization: Efforts focused on maximizing the operational capabilities of the EHR’s integrated database, ensuring it was used effectively to enhance patient health literacy and streamline educational delivery.

- HCP Training for Effective Material Use: Crucially, HCPs received targeted training on how to efficiently utilize patient education materials. This training was designed to empower them to become proficient educators, further enhancing the patient care experience.

Insight

What Helped

The enhancements in patient education significantly benefited patients and their families by fostering better engagement in medical care and promoting shared decision-making. This was underpinned by access to the most current clinical evidence and a focus on individual patient preferences. The development of an indexed educational material database proved instrumental in reducing the time needed to locate appropriate resources, streamlining the process for HCPs. Furthermore, leveraging EHR-integrated education tools, particularly electronic patient portals, and embracing digital materials reduced the reliance on printed handouts, contributing to both efficiency and sustainability. Addressing patient misconceptions through targeted education was also a key factor in improving overall health literacy.

What Went Well

The initiative was successful in engaging, encouraging, and empowering patients to take a more active role in their health and treatment decisions. This patient-centered approach led to enhanced patient satisfaction and demonstrably better health outcomes. For example, educating patients about osteopenia motivated them to adopt healthier habits, such as consistently taking vitamin D supplements, engaging in regular exercise, and making informed dietary choices, all contributing to proactive health management and promotion.

What Hindered

Challenges were encountered, primarily due to high HCP turnover rates and fluctuating schedules. These factors made it difficult to ensure consistent implementation and utilization of patient education materials across the board. Additionally, an insufficient number of HCPs were fully trained in patient education best practices, limiting the overall reach and impact of the initiative.

What Could Improve

To further enhance patient education, several areas for improvement were identified. Incorporating educational materials in video format could cater to patients who prefer visual learning or have literacy challenges. Expanding and enhancing training programs for all HCPs is crucial to ensure consistent and effective use of patient education resources, establishing a culture of proactive patient education within the healthcare setting.

Discussion

Personalized patient education is a powerful tool that actively engages, encourages, and empowers patients to become integral participants in their healthcare journey and treatment decisions. This active involvement not only leads to improved health outcomes but also reduces the necessity for excessive diagnostic testing and significantly enhances patient satisfaction [3,4,5]. Realizing these benefits requires a strong commitment and motivation from all healthcare professionals, including resident doctors, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, physicians, and allied health staff.

The Advisory Committee on Training in Primary Care Medicine (ACTPCMD) emphasizes the importance of preparing future healthcare professionals to engage patients and caregivers in shared medical decision-making. They recommend that Health Resources & Services Administration’s (HRSA) Title VII, Part C, Section 747 and 748 education and training programs should prioritize this aspect. Effective patient education is a cornerstone of achieving this shared decision-making model [6].

As HCPs, it is our professional responsibility to cultivate practices that ensure patients are well-informed about their conditions and treatment plans. This commitment not only fosters increased adherence to medication and treatment protocols but also elevates the physician-patient relationship to a more collaborative and trust-based level.

Conclusions

To significantly improve both the physical and psychosocial well-being of patients, the implementation of personalized patient education materials, supplementing verbal education from HCPs, is indispensable. This combined approach enhances patient care through shared decision-making and by boosting patient satisfaction. It is crucial to continually reinforce the message that HCPs must prioritize understanding patients’ concerns and consistently provide effective patient education and counseling as integral components of high-quality healthcare delivery.

Disclaimer: The content published in Cureus is derived from the clinical experiences and/or research of independent individuals or organizations. Cureus bears no responsibility for the scientific accuracy or reliability of the data or conclusions presented herein. All content within Cureus is intended solely for educational, research, and informational purposes. Furthermore, articles published in Cureus should not be considered substitutes for professional medical advice. Always consult with a qualified healthcare professional and do not disregard or avoid seeking professional medical advice based on content published within Cureus.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

Human Ethics

Ethics Approval: Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study.

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: This study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

References are listed in the original article.