Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, often unpredictable disease of the central nervous system, disrupting the flow of information within the brain and between the brain and body. This happens when the immune system attacks the myelin sheath, the protective layer surrounding nerve fibers, causing a range of symptoms from fatigue and numbness to vision problems and mobility difficulties. Understandably, one of the first and most pressing questions for individuals diagnosed with MS and their loved ones is about life expectancy. While an MS diagnosis can be daunting, it’s important to understand the realities of life expectancy and prognosis in the context of this condition.

Is MS a Fatal Condition?

It’s crucial to clarify upfront that multiple sclerosis is generally not considered a fatal disease in itself. People do not die from MS, but rather, some complications related to the disease can, in certain instances, become life-threatening. These complications might include severe infections, particularly pneumonia, which can arise from swallowing difficulties or reduced mobility.

Statistically, having MS can slightly reduce life expectancy compared to the general population. On average, studies suggest that individuals with MS may have a lifespan that is about five to ten years shorter. However, this is just an average, and it’s a figure that is constantly improving. Advances in treatments, better management of symptoms, and improved overall care are all contributing to closing this gap. Many people diagnosed with MS today can expect to live long and fulfilling lives.

Understanding the Progression of MS

To better understand prognosis, it’s helpful to know how MS typically progresses. For the majority of individuals, MS begins with a phase known as relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). RRMS is characterized by unpredictable attacks, also called relapses or exacerbations, during which new symptoms appear or existing ones worsen. These relapses are followed by periods of remission, where symptoms improve partially or completely.

Over time, a significant proportion of people with RRMS will transition to a phase called secondary progressive MS (SPMS). In SPMS, the disease course changes, and there is a more steady and gradual worsening of neurological function, with or without occasional relapses. The progression in SPMS is less about distinct attacks and remissions and more about a continuous accumulation of disability.

It’s important to note that the timeframe for progressing from RRMS to SPMS is highly variable. Decades ago, it was estimated that without treatment, about half of RRMS patients would progress to SPMS within 10 years of onset. However, with the advent and widespread use of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), this timeline has significantly shifted. Modern studies indicate that with treatment, the conversion rate to SPMS is much lower and occurs over a longer period.

In a smaller percentage of individuals, approximately 10-15%, MS takes a different course from the outset, known as primary progressive MS (PPMS). In PPMS, there is a gradual worsening of symptoms from the beginning, without distinct relapses or remissions.

While these categories (RRMS, SPMS, PPMS) are helpful for understanding typical disease patterns, it’s crucial to remember that MS is highly individual. The lines between these categories can blur, and individuals may experience overlaps in disease activity. Furthermore, the speed and severity of progression vary greatly from person to person.

The EDSS Scale: Tracking Disability in MS

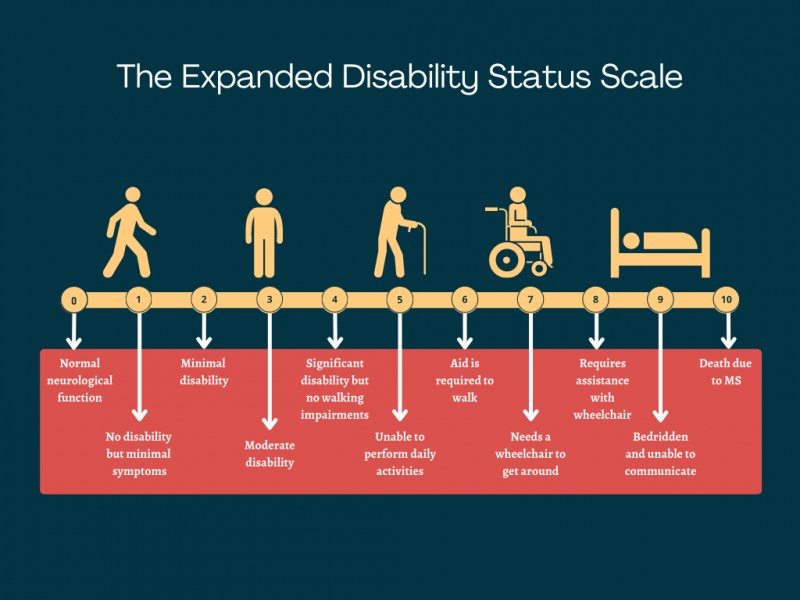

To monitor and quantify disability progression in MS, healthcare professionals often use the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). This is a standardized scale that ranges from 0 (no disability) to 10 (death due to MS). Scores increase in increments of 0.5 as disability worsens.

Initially, EDSS scores from 0 to 4.5 are primarily based on impairments in functional systems. These systems represent different neurological functions, such as:

- Pyramidal: Relating to muscle strength and limb movement.

- Cerebellar: Affecting coordination, balance, and tremor.

- Brainstem: Controlling speech, swallowing, and eye movements.

- Sensory: Involving sensations like touch, pain, and temperature.

- Bowel and Bladder: Relating to urinary and bowel control.

- Visual: Concerning vision and eye function.

- Cerebral (Mental): Impacting cognitive functions like memory and thinking.

- Other: Any other neurological findings attributed to MS.

Each of these functional systems is graded on a scale from 0 (no disability) to 5 or 6 (severe disability).

As disability progresses and EDSS scores rise from 5 to 9.5, the scale becomes more heavily weighted on walking ability. The EDSS provides a structured way to track the course of disability over time, although it’s just one tool and doesn’t capture the entire lived experience of MS.

| EDSS Score | What it Means |

|---|---|

| 0 | No signs of neurological abnormalities |

| 1 | No disability, but minimal signs in one functional system |

| 1.5 | No disability, but minimal signs in two or more functional systems |

| 2 | Minimal disability in one functional system |

| 2.5 | Minimal disability in two functional systems, or mild disability affecting one system |

| 3 | Moderate disability in one functional system or mild disability in three or four systems, without any walking difficulties |

| 3.5 | Moderate disability in one functional system, with more than minimal impairment in multiple others, but no difficulty walking |

| 4 | Significant disability, but able to function mostly independently in daily life. Able to walk 500 meters (about one-third of a mile) without aid or rest |

| 4.5 | Significant disability that may necessitate some minor help in day-to-day life. Able to walk 300 meters (about one-fifth of a mile) without aid or rest |

| 5 | Severe disability that causes substantial impairment in daily life, necessitating accommodations. Able to walk 200 meters (about a tenth of a mile) without aid or rest |

| 5.5 | Severe disability to the point that some activities that had been a part of normal day-to-day life can no longer be done independently. Able to walk 100 meters (about 330 feet) without aid or rest |

| 6 | Requires a walking aid, such as a cane or a crutch, to walk 100 meters (about 330 feet) with or without stopping to rest |

| 6.5 | Requires two walking aids, such as a pair of canes or crutches, to walk 100 meters (about 330 feet) without stopping to rest |

| 7 | Unable to walk more than a few feet, even with aid. Requires a wheelchair to get around but is still up and about for most of the day, and is able to maneuver the chair and get in and out of it independently |

| 7.5 | Unable to take more than a couple of steps, and needs help getting in and out of a wheelchair and wheeling around |

| 8 | Unable to stand, and usually reliant on a wheelchair that is motorized or pushed to get around, but still up and about for much of the day. Generally still has function in the arms and can still take care of most self-care activities |

| 8.5 | Stays in bed for most of the day, with some impairment in arm function and ability to handle self-care functions |

| 9 | Unable to get out of bed but still able to communicate clearly and eat voluntarily |

| 9.5 | Confined to bed without the ability to communicate effectively or swallow properly |

| 10 | Death due to MS |

Factors That Influence MS Prognosis and Life Expectancy

It’s essential to recognize that MS is incredibly variable. No two individuals will have the exact same experience with the disease. Many factors can influence the course of MS and, by extension, life expectancy after diagnosis.

Impact of Treatment on Prognosis

Without a doubt, one of the most significant factors influencing MS prognosis today is treatment. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) have revolutionized the management of MS. These medications work to reduce the underlying inflammatory attacks that drive the disease process. They have been proven to reduce relapse rates, slow down the accumulation of brain damage, and delay disability progression.

Early treatment initiation is a cornerstone of MS care. Starting DMTs as soon as possible after diagnosis is generally associated with better long-term outcomes. While DMTs are not a cure, they significantly alter the disease trajectory for many people. There are various DMTs available, each with its own efficacy and safety profile. Choosing the right DMT is a personalized decision made in consultation with a healthcare team.

Lifestyle Factors and Disease Course

Beyond medical treatments, lifestyle choices play a crucial role in managing MS and influencing its progression.

Exercise: Regular physical activity is strongly linked to better physical and cognitive function in people with MS. Exercise can help manage symptoms, improve mobility, and even potentially reduce brain tissue loss and relapse frequency.

Smoking: Smoking has consistently been shown to worsen MS. It’s associated with more severe disease, faster progression, and increased disability. Quitting smoking is strongly recommended for individuals with MS.

Diet: While there’s no one-size-fits-all “MS diet,” general healthy eating principles apply. A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, while low in processed foods and refined sugars, is generally recommended to support overall health and potentially influence MS.

Stress Management: Chronic stress has been implicated in MS relapses and disease progression. Finding effective stress management techniques and minimizing chronic stress can be beneficial.

Biological and Disease-Specific Factors

Several biological and disease-related factors can also impact prognosis:

Age at Onset: Generally, a younger age at MS symptom onset is associated with a slower initial disease progression, although relapse frequency might be higher earlier in life. Older age at onset may be linked to a more rapid accumulation of disability.

Early Disease Course: The pattern of MS in the initial years after diagnosis can provide prognostic information. More frequent relapses or a rapid increase in disability early on might suggest a higher risk of more significant long-term disability.

MRI Findings: Brain and spinal cord MRI scans are crucial for diagnosis and monitoring. The extent of lesions and brain atrophy seen on MRI can correlate with disease severity and progression.

Obesity: Obesity, defined as a body mass index over 30, has been linked to a more severe MS course. Excess body fat can contribute to chronic inflammation, potentially exacerbating nerve damage in MS.

Demographic Factors

Demographic factors such as race and sex also show some correlation with MS prognosis.

Race and Ethnicity: In some populations, like in the U.S., Black and Hispanic individuals with MS have been observed to experience more rapid disability worsening and potentially higher mortality rates compared to white individuals. These differences are likely multifactorial, involving genetics, socioeconomic factors, and access to care.

Sex: MS is more common in women than men, but men tend to have a somewhat poorer prognosis. Men with MS may experience less complete recovery from relapses, have a higher burden of brain damage, and are more likely to develop progressive forms of MS and reach higher levels of disability. However, women may experience more frequent relapses and brain lesions.

Living a Fulfilling Life with MS

Despite the challenges MS presents, the outlook for individuals with MS is continually improving. With advancements in DMTs and a greater understanding of lifestyle factors, many people with MS can lead full and active lives.

After an MS diagnosis, a collaborative approach between the individual and their healthcare team is crucial. This typically involves:

- Regular neurological check-ups to monitor disease activity and progression.

- Utilizing DMTs to manage the disease course.

- Symptomatic treatments to address specific symptoms like pain, fatigue, or spasticity.

- Lifestyle modifications, including exercise, diet, and stress reduction.

MS is indeed a lifelong condition, and its impact varies significantly. While some individuals may experience significant disability relatively early, others may live for decades with minimal impact on their daily lives. It’s estimated that a substantial majority of people with MS remain able to walk even 20 years after diagnosis, although some may require assistive devices.

Living well with MS involves proactive management, a positive attitude, and leveraging available resources and support systems. While the question of life expectancy after an MS diagnosis is natural, focusing on quality of life, proactive treatment, and healthy lifestyle choices is paramount.

Disclaimer: This information is intended for general knowledge and informational purposes only, and does not constitute medical advice. It is essential to consult with a qualified healthcare professional for any health concerns or before making any decisions related to your health or treatment.