This course was published in the December 2018 issue and expires December 2021.

The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose.

This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the components of dental hygiene diagnosis as represented in the professional standards of practice.

- Use the operatory chart model to create dental hygiene diagnoses in clinical practice.

- Link dental hygiene diagnoses to assessment findings and care plan procedures.

Click here to view the authors’ updated process of care operatory chart model for dental hygiene diagnosis.

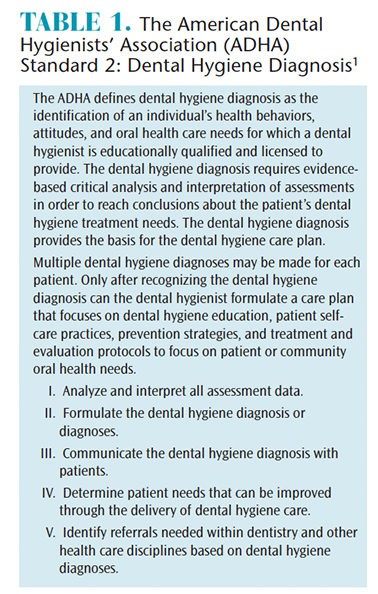

In 2016, the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) updated its standards for clinical practice.1 The section on dental hygiene diagnosis (DHDx) was expanded to recognize that dental hygienists provide multiple diagnoses for their patients, and utilize these diagnoses to formulate comprehensive care plans and facilitate intraprofessional and interprofessional referrals (Table 1).1 This evolution underscores the critical role of dental hygienists in patient care. Further solidifying this role, in November 2017, the United States Office of Management and Budget released a revised Standard Occupational Classification for 2018.2 This significant update reclassified dental hygienists from “Health Technologists and Technicians” to “Healthcare Diagnosing or Treating Practitioners,” placing them in the same esteemed category as dentists, physicians, pharmacists, registered nurses, physical therapists, and other essential healthcare diagnosticians and providers.3 This reclassification officially recognizes the diagnostic capabilities and responsibilities inherent in the dental hygiene profession.

Recent academic research has consistently demonstrated the importance of teaching dental hygiene diagnosis (DHDx) in entry-level dental hygiene programs.4 The benefits of incorporating DHDx into dental hygiene education are multifaceted. Students become more accountable for patient outcomes by improving communication regarding treatment necessities. Patient-centered, individualized treatment planning becomes more thorough and effective. The process leads to clearer patient informed consent and more efficient documentation practices. Crucially, the integration of DHDx significantly enhances students’ critical thinking abilities, preparing them for the complexities of real-world clinical practice.4

Despite the growing emphasis on DHDx in educational settings, confusion persists in practical dental environments. This confusion manifests in various ways. One common challenge is the inconsistent use of different classification systems for periodontal diseases among practitioners within the same office or across different practices.5 Another issue arises when clinicians narrowly define their DHDx scope, limiting it primarily to periodontal conditions, thereby overlooking the broader spectrum of care they are qualified to provide. Political disagreements regarding diagnostic authority further complicate the landscape. However, despite these challenges, dental hygienists are uniquely positioned to deliver comprehensive patient care by effectively leveraging their assessment skills, critical thinking abilities, and diagnostic acumen. By embracing their diagnostic role, dental hygienists can significantly enhance patient care and contribute more fully to overall oral and systemic health.

INNOVATIONS IN DENTAL HYGIENE DIAGNOSIS

In 2015, we introduced a process of care operatory chart model for DHDx, offering practical examples of diagnoses applicable in clinical settings.6 Since then, the periodontal classification system has undergone revisions to reflect the latest scientific understanding.7 Consequently, we have developed an updated process of care operatory chart model, accessible in the web version of this article. This updated model incorporates the 2018 periodontal classification framework, along with refined elements for assessment, signs and symptoms, diagnoses, and crucial dental hygiene care planning sections. These integral components of DHDx and subsequent care are essential for fostering transparent communication with patients, promoting effective collaboration with dentists, and ensuring seamless referrals to healthcare professionals in other medical disciplines.8

Patient-centered care forms the bedrock of contemporary dental hygiene practice.1 Effectively communicating dental hygiene diagnoses plays a pivotal role in helping patients understand the rationale behind recommended dental hygiene care and the benefits of both intra- and interprofessional referrals. In a 2015 systematic review, Zill et al.9 explored the concept of patient-centeredness, developing a comprehensive model encompassing 15 dimensions. Their findings highlighted “patient involvement in care” and “clinician-patient communication” as two of the most critical dimensions. When dental hygienists articulate clear and comprehensive dental hygiene diagnoses, patients are empowered with the necessary information to actively participate in their oral health journey. This informed involvement encourages adherence to recommended dental hygiene treatments and facilitates follow-through with referrals to other healthcare specialists.8 The following case studies serve to illustrate the inclusive and extensive nature of DHDx in diverse patient scenarios.

Case Studies

The following case studies are designed to guide dental hygiene clinicians in formulating comprehensive dental hygiene diagnoses and developing tailored dental hygiene care plans. These plans are directly informed by the detailed information gathered during the thorough assessment process.1

Dental hygiene diagnosisCase Study A. Robert, a 12-year-old boy, presented for a routine preventive dental hygiene appointment. His previous oral health visit was 18 months prior. Robert’s medical history included asthma, managed on an as-needed basis with a bronchial inhaler. He had not received the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, his last physical examination was a year ago, and he reported no recent hospitalizations or significant health events. His vital signs were stable: blood pressure (BP) 100/60 mmHg (right arm), pulse 64 beats per minute, respiration rate 14 breaths per minute, and body temperature 98°F. He measured 5’4” in height and weighed 125 lbs. Clinical assessment revealed generalized moderate dental biofilm, light calculus accumulation, generalized gingival inflammation, two new carious lesions, multiple areas of enamel demineralization, and existing pit and fissure sealants on all four first molars. He presented with a Class II malocclusion and mandibular anterior crowding. Risk assessment indicated that Robert participates in contact sports without a sports mouthguard, consumes sports drinks and soda daily, demonstrates a lack of interest in oral self-care practices, and possesses limited awareness of oral health prevention strategies.

Dental hygiene diagnosisCase Study A. Robert, a 12-year-old boy, presented for a routine preventive dental hygiene appointment. His previous oral health visit was 18 months prior. Robert’s medical history included asthma, managed on an as-needed basis with a bronchial inhaler. He had not received the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, his last physical examination was a year ago, and he reported no recent hospitalizations or significant health events. His vital signs were stable: blood pressure (BP) 100/60 mmHg (right arm), pulse 64 beats per minute, respiration rate 14 breaths per minute, and body temperature 98°F. He measured 5’4” in height and weighed 125 lbs. Clinical assessment revealed generalized moderate dental biofilm, light calculus accumulation, generalized gingival inflammation, two new carious lesions, multiple areas of enamel demineralization, and existing pit and fissure sealants on all four first molars. He presented with a Class II malocclusion and mandibular anterior crowding. Risk assessment indicated that Robert participates in contact sports without a sports mouthguard, consumes sports drinks and soda daily, demonstrates a lack of interest in oral self-care practices, and possesses limited awareness of oral health prevention strategies.

Examples of Appropriate DHDx:

- Asthma (as a systemic condition influencing dental hygiene care)

- Risk for medical emergency (related to asthma history)

- Risk for opportunistic infection (potential for Candida infection due to bronchodilator use, especially if rinsing is inconsistent)

- Potential for xerostomia (as a side effect of bronchodilator medication)

- Risk for anxiety related to dental visits (infrequent dental/dental hygiene appointments)

- Increased risk for oral cancer (due to lack of HPV vaccination)

- Inadequate oral self-care (manifested by biofilm, calculus, caries, and potentially linked to insufficient parental supervision)

- Knowledge deficit regarding oral health (evidenced by generalized moderate biofilm and light calculus accumulation, generalized gingival inflammation, and new caries)

- Active dental caries (presence of new lesions)

- High caries risk (dietary habits including daily sports drinks and soda consumption, presence of new caries, and enamel demineralization)

- Potential for orofacial injury (lack of sports mouthguard during contact sports)

- Gingivitis, specifically dental biofilm-induced gingivitis, with puberty recognized as a modifying systemic factor.

Potential Dental Hygiene Care Plan:

- Request patient bring bronchodilator to all future appointments to manage potential asthma exacerbations.10

- Implement stress reduction protocols during appointments due to asthma history and potential anxiety.

- Provide a physician referral for an HPV vaccination consultation and education.11

- Deliver comprehensive oral health education (emphasizing mouth rinsing after bronchodilator use, proper toothbrushing techniques, nightly fluoride rinse and/or prescription fluoride product if indicated, interproximal biofilm management strategies, dry mouth management if xerostomia is present, and education regarding oral cancer risk and the importance of HPV vaccination; reinforce all educational points with parents/guardians).

- Implement a Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA) protocol tailored for high caries risk patients.12

- Provide dietary counseling focused on reducing sugar consumption from sports drinks and soda.

- Refer to a dentist for restorative treatment of dental caries.

- Refer to an orthodontist for evaluation and management of malocclusion.

- Perform a comprehensive prophylaxis.

- Apply fluoride varnish.

- Place sealants on all erupted second molars for caries prevention.13

- Fabricate a custom sports mouthguard for injury prevention14 and provide detailed care instructions.

- Schedule a re-evaluation appointment in 6 weeks to assess progress with self-care protocols, confirm completion of referrals, evaluate gingival health, and determine the appropriate interval for the next continuing care appointment based on these findings.

Case Study B. Mary, a 32-year-old woman, is currently pregnant with her first child. Her last dental appointment was 7 months prior, which included a prophylaxis, examination, and dental radiographs. Her health, pharmacologic, and dietary history assessment revealed hyperemesis gravidarum, a severe form of morning sickness, throughout her pregnancy. Mary reported significant difficulty brushing her teeth and an inability to tolerate interdental cleaning due to nausea and vomiting triggers. Despite her efforts to maintain a healthy diet, she experienced food aversions to many foods, including meats, seafood, and most vegetables (both raw and cooked). Her diet primarily consisted of small portions of bland foods such as steamed rice, toast, mild cheese, some fruits, and frequent sips of chamomile tea. She was taking a prenatal vitamin, which often exacerbated her nausea. Her vital signs were: height 5’9”, weight 145 lbs (with a 12.5-pound weight gain during pregnancy), blood pressure 130/79 mmHg (right arm), pulse 80 beats per minute, respiration rate 20 breaths per minute, and temperature 98.6°F. Clinical assessment findings included generalized heavy biofilm accumulation on posterior teeth and light biofilm on anterior teeth, localized moderate calculus on the lingual surfaces of mandibular anterior teeth, generalized periodontal probing depths ranging from 2 mm to 4 mm, generalized gingival inflammation including inflammation around a #30 dental implant, lingual erosion on maxillary anterior teeth, and multiple teeth with existing dental restorations. Risk assessment highlighted a diet high in fermentable carbohydrates.

Examples of Appropriate DHDx:

- Pregnancy complicated by hyperemesis gravidarum (as a significant systemic factor influencing oral health and care)

- Gingivitis: Dental biofilm-induced, with pregnancy identified as a modifying systemic factor.

- Peri-implant mucositis around implant #30.

- Compromised oral self-care due to persistent vomiting.

- Elevated risk for dental caries due to a diet rich in fermentable carbohydrates and frequent vomiting episodes.

Potential Dental Hygiene Care Plan:

- Provide comprehensive oral health education tailored to pregnancy, specifically advising on post-vomiting oral hygiene practices (rinse with 8 oz of water and 1 tsp of baking soda or plain water immediately after vomiting, and postpone toothbrushing for at least 1 hour to minimize enamel damage from stomach acid exposure15–17); explain the etiology and transmission of cariogenic bacteria to newborns and the importance of early dental examinations for infants (by age 1 or within six months of the eruption of the first tooth, whichever comes first).13

- Deliver dietary counseling focused on reducing dental caries risk while ensuring adequate nutrition during pregnancy; emphasize strategies to manage cravings and aversions in a health-conscious manner.

- Provide a referral to a registered dietitian for comprehensive nutritional counseling, particularly addressing hyperemesis gravidarum and its impact on dietary intake and oral health.

- Implement a CAMBRA protocol for high caries risk management.12

- Perform a gentle prophylaxis, considering patient comfort and nausea triggers.

- Apply fluoride varnish for caries prevention.

- Treat the patient in a reclined rather than supine position to minimize nausea.

- Recommend the use of an oral irrigator with an antiseptic mouthrinse as a gentler alternative to flossing to manage biofilm, gingivitis, and peri-implant mucositis, given the patient’s difficulty with traditional interdental cleaning methods due to vomiting sensitivities.

- Schedule a re-evaluation appointment in 4 to 6 weeks to assess progress with the self-care regimen, reduction in gingivitis and peri-implant mucositis, improvement in biofilm and calculus control, and adherence to dietary counseling and dietitian referral recommendations.

PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF DENTAL HYGIENE DIAGNOSIS

The preceding case studies clearly demonstrate that a multitude of factors must be considered when formulating a dental hygiene diagnosis (DHDx). It is insufficient to identify only a single condition for management. Patients often present with complex clinical pictures, necessitating dental hygienists to thoroughly assess, evaluate, and make informed decisions. These decisions involve determining which conditions can be effectively managed within the dental hygienist’s scope of practice, which diagnoses necessitate an intraprofessional collaborative approach within the dental team, and which diagnoses require interprofessional referrals to ensure optimal patient outcomes through a broader healthcare network.

Several key concepts are crucial for understanding and effectively implementing DHDx in practice. First and foremost, diagnosis serves as the essential link between comprehensive patient assessment and patient-centered care. Patients should expect to receive a clear summary of the assessments performed and well-articulated DHDx that seamlessly integrate clinical findings, reported symptoms, examination results, and any relevant test outcomes. This diagnostic process relies heavily on clinical reasoning and the accurate labeling of patient problems, or diagnoses. This not only shapes the clinician’s understanding of the patient’s conditions but also, crucially, the patient’s own understanding of their oral health status. Furthermore, clear DHDx facilitates effective communication among all members of the healthcare team, including dentists, specialists, and the patient themselves.18,19

Secondly, comprehensive DHDx is paramount; therefore, formulating multiple diagnoses is not only appropriate but often necessary. Restricting diagnoses to a single aspect of a patient’s oral health is unnecessarily limiting and fails to fully represent the patient’s complex needs or the full capabilities and scope of practice of a dental hygienist. As highlighted in the case studies, the potential range of diagnoses is extensive and varied, reflecting the multifaceted nature of oral health and its connection to systemic health.

Beyond the clinical reasoning involved in formulating DHDx, dental hygiene practitioners must also engage in management reasoning.20 Once the DHDx is clearly established and communicated, the subsequent step involves developing and discussing the dental hygiene care plan with the patient. This collaborative process encompasses several critical elements: prioritization of treatment needs, shared decision-making with the patient regarding treatment options and goals, and ongoing monitoring of treatment progress and patient response. Patient preferences, individual societal values, logistical constraints (such as time and financial resources), resource availability within the practice and community, and cultural considerations all significantly influence management decisions. This leads to diverse pathways for achieving acceptable and patient-centered treatment outcomes.20 It’s essential to recognize that treatment plans are not static; they are fluid and dynamic documents that require continuous monitoring and adjustments based on the patient’s evolving health status and response to interventions. As a patient progresses through their care plan, their diagnosis itself may change over time (for example, periodontitis may transition into periodontitis in remission). Consequently, the care plan must be adaptable and modified accordingly to reflect these diagnostic shifts and ensure ongoing, effective patient care.

Finally, it is imperative that dental hygienists confidently affirm their ability to diagnose and actively dispel the outdated notion that they “cannot diagnose.” The established standards for clinical dental hygiene practice unequivocally state that dental hygiene diagnosis is an integral responsibility of the dental hygienist.1 While some professions may assert limitations on who can diagnose, it is crucial to recognize that there is no exclusive “monopoly” on the use of diagnostic terminology within healthcare. What is unequivocally clear is the importance of always practicing within one’s defined scope of practice for treatment.

To illustrate this point, consider periodontitis, a well-recognized diagnostic term. Physicians and nurses, during a routine patient examination, may observe and document the presence of periodontal inflammation. Within their scope of practice, they might prescribe an antimicrobial mouthrinse to manage the inflammation and appropriately refer the patient to a dental professional for further comprehensive care. These actions are well within their professional scope and demonstrate diagnostic recognition. Similarly, a dental hygienist is fully qualified to diagnose periodontitis based on their comprehensive periodontal assessment. The key difference lies in the scope of treatment each professional can provide. Within the dental hygiene scope of practice, preventive and therapeutic services such as tailored oral health education, periodontal debridement to remove biofilm and calculus, local anesthesia to enhance patient comfort during procedures, and the application of locally administered sustained-release antimicrobial products are all within their purview. A dental hygienist may also make a referral to a periodontist for more specialized or advanced periodontal treatment. Conversely, a dentist possesses the scope to provide all the preventive and therapeutic services offered by a dental hygienist, in addition to performing advanced surgical procedures for periodontal management. Crucially, all of these diverse healthcare providers are using the same fundamental diagnosis – periodontitis – to guide their respective roles in patient care.

Hypertension offers another pertinent example. Dental hygienists and dentists routinely assess vital signs and may identify hypertension as a diagnosis based on elevated blood pressure readings. They will then gather information on medications the patient is currently taking to manage hypertension and carefully consider any potential implications for providing dental care, particularly regarding the safe administration of local anesthesia. If warranted by the patient’s health status, they will proactively communicate with the patient’s physician to address any health concerns related to hypertension management. These diagnostic and management decisions are entirely appropriate and within their respective scopes of practice. However, neither dental hygienists nor dentists would prescribe antihypertensive medication, as this aspect of medical treatment falls outside their defined scope of practice. The patient’s physician or a nurse practitioner, on the other hand, will conduct a thorough medical evaluation and determine the most appropriate treatment plan for hypertension, which may include lifestyle modifications (diet, exercise) and pharmacological management with antihypertensive medications. Again, all of these healthcare professionals are utilizing the same diagnostic term – hypertension – demonstrating the shared understanding of health conditions across different disciplines, even with varying scopes of practice.

CONCLUSION

Dental hygiene diagnosis (DHDx) presents a valuable opportunity for clinicians to enhance patient understanding of their oral health status and the rationale behind proposed care plans. A full scope of dental hygiene practice necessitates a strong and explicit link between comprehensive assessment data and the development of a tailored dental hygiene care plan. Every treatment procedure planned and executed should be directly linked to a clearly articulated DHDx. Dental hygienists must confidently embrace their essential role as diagnosticians and consistently utilize the comprehensive dental hygiene process of care in their daily practice. This commitment to diagnosis-driven care is fundamental to ensuring optimal oral health outcomes and contributing significantly to the overall well-being of their patients.

REFERENCES

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- United States Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2010 Standard Occupational Classification. Available at: bls.gov/soc/2010/2010_major_groups.htm. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- United States Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2018 Standard Occupational Classification. Available at: bls.gov/soc/2018/major_groups.htm. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- Gurenlian JR, Sanderson TR, Garland K, Swigart D. Exploring the integration of the dental hygiene diagnosis in entry-level dental hygiene curricula. J Dent Hyg. 2018;92:18–26.

- French KE, Perry KR, Boyd LD, et al. Variations in periodontal diagnosis among clinicians: dental hygienists’ experiences and perceived barriers. J Dent Hyg. 2018;92:23–30.

- Swigart DJ, Gurenlian JR. Implementing dental hygiene diagnosis into practice. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2015;13(9):56–59.

- Caton JG, Armitage G, Berglundh T, et al. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions—Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S1–S8.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Dental Hygiene Diagnosis: an ADHA White Paper. Available at: eiseverywhere.com/esurvey/index.php?surveyid=40570. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- Zill JM, Scholl I, Harter M, Dirmaier J. Which dimensions of patient-centeredness matter? Results of a web-based expert Delphi survey. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:1–15.

- Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL. Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. 8th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2013:106.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinician FAQ: CDC Recommendations for HPV Vaccine 2-Dose Schedules. Available at: cdc.gov/hpv/downloads/HCVG15-PTT-HPV-2Dose.pdf. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- Jenson L, Budenz AW, Featherstone JD, Ramos-Gomez FJ, Spolski VW, Young DA. Clinical protocols for caries management by risk assessment. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:714–723.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Best practices on periodicity of examination, preventive dental services, anticipatory guidance/counseling, and oral treatment for infants, children, and adolescents. Available at: aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/BP_Periodicity.pdf#page=5&zoom=auto,-274,495. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on Prevention of Sports-Related Orofacial Injuries. Available at: aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/P_Sports.pdf. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- Burkhart NW. Preventing dental erosion in the pregnant patient. RDH. 2012;32(1):72–73.

- Johnson CD, Koh SH, Shynett B, et al. An uncommon dental presentation during pregnancy resulting from multiple eating disorders: Pica and bulimia. Gen Dent. 2006;54:198–200.

- Lane MA. Effect of pregnancy on periodontal and dental health. Acta Odontol Scand. 2002;60:257–264.

- Gruppen LD, Frohna AZ. Clinical reasoning. In: Norman GR, van der Vleuten CPM, Newble DL, eds. International Handbook of Research in Medical Education. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2002:205–230.

- Ilgen JS, Eva KW, Regehr G. What’s in a label? IS diagnosis the start or the end of clinical reasoning? J Gen Intern Med. 2016:31:435–437.

- Cook DA, Sherbino J, Durning SJ. Management reasoning: Beyond the diagnosis. JAMA. 2018:319:2267–2268.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2018;16(12):36–39.