Mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) is increasingly recognized as a potential diagnosis for individuals experiencing a range of symptoms affecting various body systems, including the skin, gastrointestinal tract, cardiovascular system, and often accompanied by neurological complaints. Patients with these symptoms frequently undergo extensive medical evaluations by specialists across different fields, often without receiving a clear diagnosis until MCAS is considered. However, MCAS is not yet universally accepted as a distinct medical condition, and definitive diagnostic criteria are still evolving. Based on current knowledge of mast cell activation and its effects, this article aims to explore and propose criteria for MCAS diagnosis. These proposed criteria will be discussed in relation to other mast cell disorders and conditions with similar symptoms, providing a foundation for future research and validation.

A Look Back at Mast Cell Activation Concepts

The concept of “mast cell activation disorders,” characterized by sudden mediator release without mast cell proliferation, began gaining traction in medical literature in the late 1980s. This possibility was considered at a consensus conference focused on classifying systemic mastocytosis variants. The conference acknowledged the potential for “unknown diseases of mast cell activation,” suggesting that some individuals might have mast cells that activate more easily or are less resistant to degranulation triggers. This idea offered an explanation for unexplained flushing or anaphylaxis, attributing it to an abnormal sensitivity of mast cells rather than an increased sensitivity to histamine itself. It was also suggested that such “systemic mastocyte activation” could be identified through biochemical markers. The concept of such a syndrome could explain symptoms resembling mast cell proliferative disorders in patients who did not meet the diagnostic criteria for those diseases.

In the diagnostic process for suspected MCAS, patients presenting with symptoms like flushing, itching, unexplained low blood pressure, gastrointestinal issues, and fluctuating blood pressure often start with evaluations by general practitioners. Common causes for these symptoms are typically ruled out first. Patients might then be referred for allergy testing. If these evaluations are negative, a logical next step is to consider a possible, but previously unrecognized, mast cell proliferative disorder. If systemic mastocytosis is ruled out, one possibility is a mast cell-related condition where the mast cell population isn’t increased, as in proliferative disorders, but rather, the mast cells are hyperresponsive.

Support for the idea of hyperactive mast cells in disease comes from the acceptance of monoclonal mast cell activation syndrome (MMAS). MMAS was defined at a consensus conference to describe patients experiencing unprovoked anaphylaxis who met one or two minor criteria for mastocytosis but not the full criteria. The recognition of MMAS followed observations that patients with mastocytosis had a surprisingly high prevalence of idiopathic hypotension, similar to idiopathic anaphylaxis. This led researchers to investigate patients diagnosed with idiopathic anaphylaxis to see if some had minor mastocytosis criteria or occult mastocytosis, which turned out to be the case. Further supporting this was experimental evidence showing that NTAL (LAT 2), a common adaptor molecule, could be phosphorylated at rest by KIT with the D816V mutation found in mastocytosis. This hyperphosphorylation of NTAL enhanced IgE-mediated mast cell activation.

Based on these findings, the mastocytosis consensus conference acknowledged MMAS. The diagnosis of MMAS was further supported by subsequent research. More recent studies have shown that patients with anaphylaxis from insect stings often have mastocytosis or a monoclonal mast cell population, highlighting an increased sensitivity to anaphylaxis in these individuals.

Mast Cells and Their Mediators: Key Players in MCAS

Mast cells originate from hematopoietic stem cells and mature in tissues. They are concentrated in areas like mucosal and endothelial surfaces, where the body interacts with the external environment. This location aligns with their role as sentinels of both the innate and adaptive immune systems. While their precise role in maintaining health is still being understood, mast cells are frequently associated with allergic diseases.

Stem cell factor (SCF) is a major cytokine involved in mast cell growth and differentiation. SCF can also enhance IgE-mediated mast cell degranulation and act as a chemotactic factor. SCF works through KIT, a transmembrane receptor encoded by the c-Kit proto-oncogene, which has tyrosine kinase activity. KIT is activated when SCF cross-links it. KIT activation is also known to boost IgE-mediated mast cell activation. The D816V point mutation in KIT leads to constitutive activation of its tyrosine kinase domain, causing SCF-independent autophosphorylation.

Mast cells can be activated through both IgE-dependent and IgE-independent mechanisms. Regardless of the activation pathway, mast cell activation leads to:

- Degranulation: Release of preformed mediators stored in granules, including histamine, heparin, proteases, and cytokines like TNF-α.

- De novo synthesis of arachidonic acid metabolites: Production of mediators like PGD2 and LTC4 from membrane lipids.

- Synthesis and secretion of cytokines and chemokines.

Classifying Mast Cell Activation-Related Diseases

Mast cells are crucial in the development or progression of various diseases, ranging from primary mast cell disorders like mastocytosis to conditions where mast cells are recruited through external mechanisms, leading to “secondary” mast cell activation.

Table I: Classification of Diseases Associated with Mast Cell Activation

| Primary Mast Cell Activation Disorders* | Secondary Mast Cell Activation Disorders*+ | Idiopathic Mast Cell Activation Disorders*#~ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mast Cell Proliferation | Mastocytosis | Chronic Eosinophilic Leukemia with Increased Mast Cells | |

| Mast Cell Activation (No Proliferation) | Monoclonal Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MMAS) | Allergic Diseases, Autoimmune Urticaria, Physical Urticarias, Inflammatory Disorders, Infections, Drug Reactions | Idiopathic Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS), Idiopathic Anaphylaxis, Idiopathic Angioedema |

*See text for explanation

+Requires a primary stimulation

#When mast cell degranulation has been documented; may be either primary or secondary. Note also that angioedema may be associated with hereditary or acquired angioedema where it may be mast cell independent and result from kinin generation.

~See text and Table II for proposed diagnostic criteria

Primary Mast Cell Activation Disorders

Currently, two well-defined acquired molecular defects are known to cause mast cell proliferation: the D816V point mutation in c-Kit, associated with mastocytosis, and the FIP1L1-PDGFRA translocation, linked to chronic eosinophilic leukemia with increased mast cells. The latter primarily results in symptoms related to eosinophil proliferation.

Patients with systemic mastocytosis often experience episodic symptoms of mast cell activation, such as flushing, lightheadedness, and gastrointestinal cramping. However, some individuals with systemic mastocytosis may remain asymptomatic for years, even with a high mast cell burden.

The D816V c-Kit gain-of-function mutation is found in over 90% of adult systemic mastocytosis cases. The diagnostic standard for systemic mastocytosis is the presence of multifocal mast cell clusters with atypical morphology in a bone marrow biopsy. This is considered a major diagnostic criterion. Minor criteria include a tryptase level above 20 ng/ml, atypical mast cell morphology (spindle-shaped, hypogranulated), abnormal CD2 and CD25 expression on mast cells, and detection of a codon 816 c-Kit mutation. WHO guidelines require at least one major and one minor criterion, or three minor criteria, for a mastocytosis diagnosis. Urticaria pigmentosa skin lesions are present in about 80% of mastocytosis patients.

A subset of patients with recurrent anaphylaxis has been found to have clonal mast cells, indicated by one or more minor mastocytosis criteria like abnormal mast cell morphology, CD25 expression, and/or the c-Kit D816V mutation. A consensus conference recognized that patients with just one or two minor mastocytosis criteria have MMAS. These patients typically present with episodic mast cell degranulation symptoms, most commonly flushing, lightheadedness, and abdominal symptoms like cramping, nausea, and diarrhea. Episodes can progress to loss of consciousness and life-threatening hypotension, lasting from minutes to hours. Triggers are often unidentified, though some events are linked to insect stings, eating, and exercise (without food-specific IgE allergy). These patients lack the bone marrow mast cell clusters seen in mastocytosis (≥15 mast cells) and often have normal or slightly elevated serum tryptase levels. The D816V mutation may only be detectable in mast cell-enriched bone marrow samples, not in peripheral blood or unfractionated bone marrow. Microscopic examination of bone marrow mast cells can reveal hypogranulated and spindle-shaped mast cells, sometimes forming small clusters (<15 mast cells).

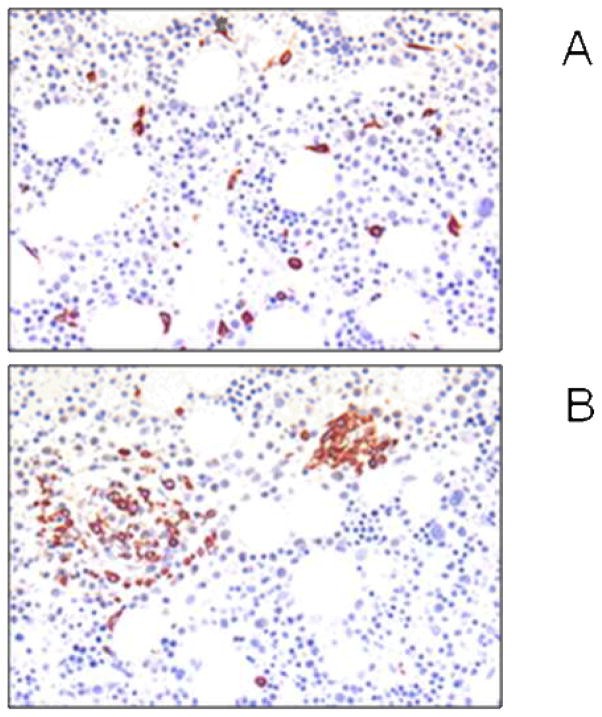

Figure 1. Bone marrow findings in patients with mast cell activation disorders.

Bone marrow analysis in mast cell activation disorders. Panel A shows tryptase-stained bone marrow sections with scattered spindle-shaped mast cells without dense aggregates, indicative of monoclonal mast cell activation syndrome (MMAS). Panel B displays small multifocal mast cell aggregates, some exceeding 15 mast cells, expressing CD25, consistent with systemic mastocytosis.

Some MMAS patients may have been previously diagnosed with idiopathic anaphylaxis or exercise-induced anaphylaxis. There’s also strong evidence that a significant number of individuals experiencing anaphylaxis with hypotension after insect stings, who also have elevated baseline tryptase levels, either have occult systemic mastocytosis, bone marrow mastocytosis, or meet MMAS criteria.

Secondary Mast Cell Activation Disorders

Secondary mast cell activation occurs in allergic diseases. Symptoms can range from infrequent to frequent, and the resulting disease can be sporadic or chronic. Pathology arises from the aggregation of high-affinity IgE receptors by allergen-bound IgE. Mast cells can also be activated through non-IgE mechanisms, including IgG, complement, microbial components, drugs, hormones, physical and emotional stimuli, and cytokines. These non-IgE pathways are involved in non-allergic inflammatory conditions like chronic autoimmune urticaria and physical urticarias. IFN-γ can induce human mast cells to increase high-affinity IgG receptors, and cross-linking these receptors can trigger mast cell degranulation. This mechanism may be active in autoimmune diseases rich in IFN-γ, such as psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease. Complement activation products C3a and C5a can activate certain mast cell types (e.g., skin mast cells, mast cells in rheumatoid arthritis) by directly binding to their receptors on the mast cell surface. Complement-induced mast cell activation can contribute to symptoms in infectious, autoimmune, and neoplastic diseases. Infectious agents can also directly stimulate mast cells via toll-like receptors (TLRs) that recognize molecular patterns common to microbial or viral pathogens. Human mast cells express TLRs 1–7 and 9 and respond to TLR stimulation by releasing cytokines and LTC4. Drugs like opioid analgesics, adenosine, and vancomycin can cause itching, flushing, and bronchoconstriction by directly activating mast cells. Hypersensitivity reactions to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that inhibit the cyclooxygenase pathway have been linked to a shift in arachidonic acid metabolism towards the 5-lipoxygenase pathway, leading to leukotriene overproduction and symptoms. If symptoms consistently occur after using such a drug, it indicates a drug reaction, not MCAS. However, if symptoms occur independently of NSAID use, MCAS could still be a possibility.

Idiopathic Mast Cell Activation

Given the established role of mast cells in urticaria, angioedema, and anaphylaxis, patients with these conditions lacking an identifiable cause are categorized as idiopathic. However, the search for the underlying causes of these idiopathic disorders must continue, including the possibility that mast cell activation in these cases may be related to unidentified endogenous or environmental stimuli, or intrinsic mast cell defects resulting in a hyperactive mast cell phenotype.

It is also possible that some idiopathic events are due to basophil activation instead of, or in addition to, mast cell activation. Selective basophil activation could be due to differences in cell surface receptor expression between basophils and mast cells. Certain triggers of mediator release might preferentially activate basophils.

Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for Idiopathic Mast Cell Activation Syndrome

The existence of a distinct idiopathic MCAS, after ruling out MMAS, is not universally agreed upon. Despite the lack of consensus on objective diagnostic guidelines, some patients with unexplained symptoms are diagnosed with this syndrome, particularly when extensive evaluations fail to identify another cause.

Therefore, we propose that MCAS diagnosis is appropriate when primary and secondary causes of mast cell activation are excluded, and the following three criteria are met:

Table II: Proposed Criteria for the Diagnosis of Mast Cell Activation Syndrome*

| Criteria | Description